University Microfilms, a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

York Guilds and the Corpus Christi Plays: Unwilling Participants?

Early Theatre 9.2 Clifford Davidson York Guilds and the Corpus Christi Plays: Unwilling Participants? Almost a century ago Maud Sellers commented regarding the Corpus Christi pageants of York that the ‘sorely burdened craftsmen’ who staged them ‘found the upkeep of the plays an intolerable and vexatious burden’.1 Miss Sellers’ remark deserves to be explored, for some scholars continue to suggest or imply that the York plays were found onerous, an unwelcome financial burden placed upon unwilling citizens of the city by the mayor and corporation that control- led their guilds.2 Heather Swanson, for example, exposes a lack of perspective in her remark that the ‘[c]raft guilds took a rather more jaundiced view of the pageants, because of the expense they entailed’.3 There is, of course, sufficient evidence of guild resistance if we look at the ways in which the plays were funded, in part through a system of fines divided between support of the pageants and of the corporation. Then, craft guilds ordered to contribute to others’ pageants were often unenthusiastic, as shown by the heavy fines with which they were threatened if they did not pay their allotted shares. Refusal to pay the required subsidies and pageant money, or even ‘grudgyng or gevyng any evill woordes’, was treated as rebellion against authority.4 There were also individual cases of complaint about the cost of the plays to which a company had been assigned, for how could it be otherwise in the declining economy of a town in which severe shifts in social structure and a shrinking -

9 April 2009 Volume: 19 Issue: 06 Greedy Easter Story Andrew Hamilton

9 April 2009 Volume: 19 Issue: 06 Greedy Easter story Andrew Hamilton ........................................1 Asylum seeker love Tim Kroenert ...........................................3 On Roos ‘Chookgate’ and footy’s duty of care Andrew Hamilton ........................................5 Broadband deal better late than never John Wicks .............................................7 Indonesia veering towards extremism Peter Kirkwood ..........................................9 Easter poems Various .............................................. 11 Poor nations could lead recovery Michael Mullins ......................................... 14 Hitchcock’s Easter drama Scott Stephens ......................................... 16 Pakistan is not doomed Kimberley Layton ....................................... 18 Seductive melancholy of a poet’s last works Carolyn Masel .......................................... 20 The popes versus the free market Bruce Duncan .......................................... 22 Affectionate portraits of ‘the outsider’ Tim Kroenert ........................................... 24 Dissecting rebel priest’s heresy Andrew Hamilton ........................................ 26 A farmer’s life Gabrielle Bridges ........................................ 28 My well planned salvation Ian C. Smith .......................................... 31 Rehabilitating Stalin Ben Coleridge .......................................... 34 Conway’s maverick way Paul Collins ............................................ 37 The politicisation of defence -

The Bible in Music

The Bible in Music 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb i 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM The Bible in Music A Dictionary of Songs, Works, and More Siobhán Dowling Long John F. A. Sawyer ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiiiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by Siobhán Dowling Long and John F. A. Sawyer All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dowling Long, Siobhán. The Bible in music : a dictionary of songs, works, and more / Siobhán Dowling Long, John F. A. Sawyer. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8108-8451-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-8452-6 (ebook) 1. Bible in music—Dictionaries. 2. Bible—Songs and music–Dictionaries. I. Sawyer, John F. A. II. Title. ML102.C5L66 2015 781.5'9–dc23 2015012867 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

Easter Resources (Selected Titles – More Will Be Added) Available To

Easter Resources (selected titles – more will be added) available to borrow from the United Media Resource Center http://www.igrc.org/umrc Contact Jill Stone at 217-529-2744 or by e-mail at [email protected] or search for and request items using the online catalog Key to age categories: P = preschool e = lower elementary (K-Grade 3) E = upper elementary (Grade 4-6) M = middle school/ junior high H = high school Y = young adult A = adult (age 30-55) S = adult (age 55+) DVDs: 24 HOURS THAT CHANGED THE WORLD (120032) Author: Hamilton, Adam. This seven-session DVD study will help you better understand the events that occurred during the last 24 hours of Jesus' life; to see more clearly the theological significance of Christ's suffering and death; and to reflect upon the meaning of these events for your life. DVD segments: Introduction (1 min.); 1) The Last Supper (11 min.); 2) The Garden of Gethsemane (7 min.); 3) Condemned by the Righteous (9 min.); 4) Jesus, Barabbas, and Pilate (9 min.); 5) The Torture and Humiliation of the King (9 min.); 6) The Crucifixion (13 min.); 7) Christ the Victor (11 min.); Bonus: What If Judas Had Lived? (5 min.); Promotional segment (1 min.). Includes leader's guide and hardback book. Age: YA. 77 Minutes. Related book: 24 HOURS THAT CHANGED THE WORLD: 40 DAYS OF REFLECTION (811018) Author: Hamilton, Adam. In this companion volume that can also function on its own, Adam Hamilton offers 40 days of reflection and meditation enabling us to pause, dig deeper, and emerge changed forever. -

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as Representation of Women in Media Sara Mecatti Prof. Emiliana De Blasio Matr. 082252 SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Index 1. History of Comic Books and Feminism 1.1 The Golden Age and the First Feminist Wave………………………………………………...…...3 1.2 The Early Feminist Second Wave and the Silver Age of Comic Books…………………………....5 1.3 Late Feminist Second Wave and the Bronze Age of Comic Books….……………………………. 9 1.4 The Third and Fourth Feminist Waves and the Modern Age of Comic Books…………...………11 2. Analysis of the Changes in Women’s Representation throughout the Ages of Comic Books…..........................................................................................................................................................15 2.1. Main Measures of Women’s Representation in Media………………………………………….15 2.2. Changing Gender Roles in Marvel Comic Books and Society from the Silver Age to the Modern Age……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.3. Letter Columns in DC Comics as a Measure of Female Representation………………………..23 2.3.1 DC Comics Letter Columns from 1960 to 1969………………………………………...26 2.3.2. Letter Columns from 1979 to 1979 ……………………………………………………27 2.3.3. Letter Columns from 1980 to 1989…………………………………………………….28 2.3.4. Letter Columns from 19090 to 1999…………………………………………………...29 2.4 Final Data Regarding Levels of Gender Equality in Comic Books………………………………31 3. Analyzing and Comparing Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) in a Framework of Media Representation of Female Superheroes…………………………………….33 3.1 Introduction…………………………….…………………………………………………………33 3.2. Wonder Woman…………………………………………………………………………………..34 3.2.1. Movie Summary………………………………………………………………………...34 3.2.2.Analysis of the Movie Based on the Seven Categories by Katherine J. -

The Castle and the Virgin in Medieval

I 1+ M. Vox THE CASTLE AND THE VIRGIN IN MEDIEVAL AND EARLY RENAISSANCE DRAMA John H. Meagher III A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 1976 Approved by Doctoral Committee BOWLING GREEN UN1V. LIBRARY 13 © 1977 JOHN HENRY MEAGHER III ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 11 ABSTRACT This study examined architectural metaphor and setting in civic pageantry, religious processions, and selected re ligious plays of the middle ages and renaissance. A review of critical works revealed the use of an architectural setting and metaphor in classical Greek literature that continued in Roman and medieval literature. Related examples were the Palace of Venus, the House of Fortune, and the temple or castle of the Virgin. The study then explained the devotion to the Virgin Mother in the middle ages and renaissance. The study showed that two doctrines, the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption of Mary, were illustrated in art, literature, and drama, show ing Mary as an active interceding figure. In civic pageantry from 1377 to 1556, the study found that the architectural metaphor and setting was symbolic of a heaven or structure which housed virgins personifying virtues, symbolically protective of royal genealogy. Pro tection of the royal line was associated with Mary, because she was a link in the royal line from David and Solomon to Jesus. As architecture was symbolic in civic pageantry of a protective place for the royal line, so architecture in religious drama was symbolic of, or associated with the Virgin Mother. -

The Dramaturgy of Thomas Heywood 1594-1613 Carson, R

The dramaturgy of Thomas Heywood 1594-1613 Carson, R. Neil The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/jspui/handle/123456789/1390 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] THE DRAMATURGYOF THOMAS HEYWOOD 1594-1613 THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR JANUARY, 1974 OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE R. NEIL CARSON UNIVERSITY OF LONDON WESTFIELD COLLEGE I)IN 1 ABSTRACT This dissertation is an attempt to describe the characteristics of Thomas Heywood's dramatic style. The study is divided into three parts. The first deals with the playwright's theatrical career and discusses how his practical experience as actor and sharer might have affected his technique as a dramatic writer. The second part defines the scope of the investigation and contains the bulk of the analysis of Heywood's plays. My approach to the mechanics of playwriting is both practical and theoretical. I have attempted to come to an understanding of the technicalities of Heywood's craftsmanship by studying the changes he made in Sir Thomas Moore and in the sources he used for his plays. At the same time, I have tried to comprehend the aesthetic framework within which he worked by referring to the critical ideas of the period and especially to opinions expressed by Heywood him- self in An Apology for Actors and elsewhere. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

NPC Worship Bulletin PDF®

April 13, 2014 The National Presbyterian Church A MINISTRY OF GRACE, PASSIONATE ABOUT CHRIST’S MISSION IN THE WORLD PALM SUNDAY Lo, your king comes to you; triumphant and victorious is he, humble and riding on a donkey Zechariah 9:9 Dr. David Renwick, Senior Pastor . Dr. Quinn Fox, Associate Pastor Rev. Donna Marsh, Associate Pastor . Rev. Evangeline Taylor, Associate Pastor Parish Associates: Rev. Nancy T. Fox and Dr. Donald R. Wilson Rev. Michael Denham, Director of Music Ministries William Neil, Organist . Hilda Gore, Contemporary Music Leader Order of Worship 9:15 & 11 a.m. Kindly turn off your cell phone and other electronic devices. Entering God’s Presence Prelude Prelude in E flat Major BWV 552 J.S. Bach Erik Suter, guest organist Call to Worship Rev. Donna Marsh One Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion! Isaiah 9:6 All Shout aloud, O daughter of Jerusalem! One Lo, your king comes to you; All Triumphant and victorious is he; humble and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey. Hymn Hosanna, Loud Hosanna Ellacombe Children and Chancel Choir in procession: Hosanna to the King of Kings! Hosanna, let the praises ring! Hosanna to the King of Kings! Hosanna, let them ring! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord. Hosanna! Hosanna to the King of Kings! Hosanna to the King! p Congregation standing, singing as directed Hosanna, loud hosanna the little children sang. Through pillared court and temple the lovely anthem rang. To Jesus, who had blessed them close folded to his breast, The children sang their praises, the simplest and the best. -

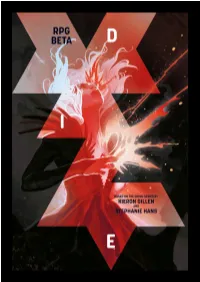

DIE RPG Beta Manual V1.Pdf

DIE: A ROLE-PLAYING GAME KIERON GILLEN ©2019 ART BY STEPHANIE HANS COVER DESIGN BY RIAN HUGHES Copyright © 2019 Kieron Gillen Ltd & Stéphanie Hans. All rights reserved. DIE, the Die logos, and the likenesses of all characters herein or hereon are trademarks of Kieron Gillen Ltd & Stéphanie Hans. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means (except for short excerpts for journalistic or review purposes) without the express written permission of Kieron Gillen Ltd or Stéphanie Hans. All names, characters, events, and places herein are entirely fictional. Any resemblance to actual persons (living or dead), events, or places is coincidental. Representation: Law Offices of Harris M. Miller II, P.C. ([email protected]) CONTENTS 1) INTRODUCTION 2) THE WORLD OF DIE 3) PREPARATION 4) THE FIRST SESSION 5) PREPARING THE SECOND SESSION 6) THE SECOND SESSION 7) THE RULES 8) RUNNING THE ARCHETYPES 9) ADVICE FOR GAMESMASTERS 10) OTHER RESOURCES WELCOME I have a habit of being a little extra around my comics. I fear this is the most extra thing I’ve ever done. Alongside creating the comic DIE with Stephanie Hans, I developed the role-playing game you hold in your hands. Er… figure of speech. “PDF on your hard drive” doesn’t quite have the same ring. This RPG creates, in a miniaturized form, your own version of the first arc of DIE. As such, there’s some possible structural spoilers for the comic. I say “possible” because it really is your own version of the comic. -

A Poetics of Uncertainty: a Chorographic Survey of the Life of John Trevisa and the Site of Glasney College, Cornwall, Mediated Through Locative Arts Practice

VAL DIGGLE: A POETICS OF UNCERTAINTY A poetics of uncertainty: a chorographic survey of the life of John Trevisa and the site of Glasney College, Cornwall, mediated through locative arts practice By Valerie Ann Diggle Page 1 VAL DIGGLE: A POETICS OF UNCERTAINTY VAL DIGGLE: A POETICS OF UNCERTAINTY A poetics of uncertainty: a chorographic survey of the life of John Trevisa and the site of Glasney College, Cornwall, mediated through locative arts practice By Valerie Ann Diggle Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of the Arts London Falmouth University October 2017 Page 2 Page 3 VAL DIGGLE: A POETICS OF UNCERTAINTY VAL DIGGLE: A POETICS OF UNCERTAINTY A poetics of uncertainty: a chorographic survey of the life of John Trevisa and the site of Glasney College, Penryn, Cornwall, mediated through locative arts practice Connections between the medieval Cornishman and translator John Trevisa (1342-1402) and Glasney College in Cornwall are explored in this thesis to create a deep map about the figure and the site, articulated in a series of micro-narratives or anecdotae. The research combines book-based strategies and performative encounters with people and places, to build a rich, chorographic survey described in images, sound files, objects and texts. A key research problem – how to express the forensic fingerprint of that which is invisible in the historic record – is described as a poetics of uncertainty, a speculative response to information that teeters on the brink of what can be reliably known. This poetics combines multi-modal writing to communicate events in the life of the research, auto-ethnographically, from the point of view of an artist working in the academy. -

2.2 Final.Indd

Wickedly Devotional Comedy in the York Temptation of Christ1 Christopher Crane United States Naval Academy Make rome belyve, and late me gang! [let me pass!] Who makes here al þis þrang? High you hense, high myght ou hang Right with a roppe. I drede me þat I dwelle to lang [I’m delayed too long] To do a jape. [mischief, joke] (York Plays 22.1-6) Satan opens the York Temptation of Christ2 pageant with these words, employing a complex and subtle rhetorical comedy aimed at moving fi fteenth-century spectators toward lives of greater devotion. With “late me gang!” Satan (“Diabolus” in the text) achieves more in these lines than just making a scene; he draws his audience members into the action. Medieval staging in York likely had Satan approach the pageant wagon stage through the audience, addressing them as he enters. As spectators respond, perhaps stepping aside, smiling, or even egging him on, they both submit to and celebrate him. However, the central action of this pageant is Christ’s successful resistance to the devil’s efforts to entice him to sin.3 Theologically and thematically, this victory parallels the pageant of Adam and Eve’s temptation earlier in the cycle4 and establishes Christ’s qualifi cation to redeem the fall of mankind with his death, which follows in the series of passion pageants that follow this scene. If the purpose of this pageant is to illustrate Christ’s victory, why does it open with this entertaining portrayal of Satan? Why not portray Jesus in prayer or meditating on the Scriptures he will use to resist Satan’s tactics? Can the pageant provide an orthodox message about the devil after endowing him with such charisma? The exemplary and biblical nature of the mystery plays in general (whether humorous or not) gives them a homiletic quality that frequently invites the audience to 29 30 Christopher Crane participate vicariously in the enacted stories and to appropriate the lessons of Scripture.