Australia's Oldest Wreck. English East India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue Summer 2012

JONATHAN POTTER ANTIQUE MAPS CATALOGUE SUMMER 2012 INTRODUCTION 2012 was always going to be an exciting year in London and Britain with the long- anticipated Queen’s Jubilee celebrations and the holding of the Olympic Games. To add to this, Jonathan Potter Ltd has moved to new gallery premises in Marylebone, one of the most pleasant parts of central London. After nearly 35 years in Mayfair, the move north of Oxford Street seemed a huge step to take, but is only a few minutes’ walk from Bond Street. 52a George Street is set in an attractive area of good hotels and restaurants, fine Georgian residential properties and interesting retail outlets. Come and visit us. Our summer catalogue features a fascinating mixture of over 100 interesting, rare and decorative maps covering a period of almost five hundred years. From the fifteenth century incunable woodcut map of the ancient world from Schedels’ ‘Chronicarum...’ to decorative 1960s maps of the French wine regions, the range of maps available to collectors and enthusiasts whether for study or just decoration is apparent. Although the majority of maps fall within the ‘traditional’ definition of antique, we have included a number of twentieth and late ninteenth century publications – a significant period in history and cartography which we find fascinating and in which we are seeing a growing level of interest and appreciation. AN ILLUSTRATED SELECTION OF ANTIQUE MAPS, ATLASES, CHARTS AND PLANS AVAILABLE FROM We hope you find the catalogue interesting and please, if you don’t find what you are looking for, ask us - we have many, many more maps in stock, on our website and in the JONATHAN POTTER LIMITED gallery. -

Geographic Board Games

GSR_3 Geospatial Science Research 3. School of Mathematical and Geospatial Science, RMIT University December 2014 Geographic Board Games Brian Quinn and William Cartwright School of Mathematical and Geospatial Sciences RMIT University, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract Geographic Board Games feature maps. As board games developed during the Early Modern Period, 1450 to 1750/1850, the maps that were utilised reflected the contemporary knowledge of the Earth and the cartography and surveying technologies at their time of manufacture and sale. As ephemera of family life, many board games have not survived, but those that do reveal an entertaining way of learning about the geography, exploration and politics of the world. This paper provides an introduction to four Early Modern Period geographical board games and analyses how changes through time reflect the ebb and flow of national and imperial ambitions. The portrayal of Australia in three of the games is examined. Keywords: maps, board games, Early Modern Period, Australia Introduction In this selection of geographic board games, maps are paramount. The games themselves tend to feature a throw of the dice and moves on a set path. Obstacles and hazards often affect how quickly a player gets to the finish and in a competitive situation whether one wins, or not. The board games examined in this paper were made and played in the Early Modern Period which according to Stearns (2012) dates from 1450 to 1750/18501. In this period printing gradually improved and books and journals became more available, at least to the well-off. Science developed using experimental techniques and real world observation; relying less on classical authority. -

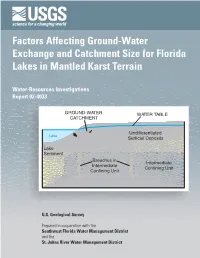

Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain

Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4033 GROUND-WATER WATER TABLE CATCHMENT Undifferentiated Lake Surficial Deposits Lake Sediment Breaches in Intermediate Intermediate Confining Unit Confining Unit U.S. Geological Survey Prepared in cooperation with the Southwest Florida Water Management District and the St. Johns River Water Management District Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain By T.M. Lee U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4033 Prepared in cooperation with the SOUTHWEST FLORIDA WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT and the ST. JOHNS RIVER WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT Tallahassee, Florida 2002 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. GROAT, Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Suite 3015 Box 25286 227 N. Bronough Street Denver, CO 80225-0286 Tallahassee, FL 32301 888-ASK-USGS Additional information about water resources in Florida is available on the World Wide Web at http://fl.water.usgs.gov CONTENTS Abstract................................................................................................................................................................................. -

A High-Quality Historical Humidity Database for Australia

The Centre for Australian Weather and Climate Research A partnership between CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology A High-quality Historical Humidity Database for Australia Chris Lucas CAWCR Technical Report No. 024 July 2010 A High-quality Historical Humidity Database for Australia Chris Lucas1 1The Centre for Australian Weather and Climate Research - a partnership between CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology CAWCR Technical Report No. 024 July 2010 ISSN: 1835-9884 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Lucas, Chris. Title: A High-quality Historical Humidity Database for Australia [electronic resource] / Chris Lucas. ISBN: 9781921605864 (pdf) Series: CAWCR technical report; 24. Notes: Included bibliography references and index. Subjects: Humidity--Australia--Databases. Meteorology--Australia--Databases. Australia--Climate. Dewey Number: 551.5710994 Enquiries should be addressed to: Chris Lucas Centre for Australian Weather & Climate Research GPO Box 1289 Melbourne Victoria 3001, Australia [email protected] Copyright and Disclaimer © 2010 CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology. To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology. CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology advise that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. No reliance or actions must therefore be made on that information without seeking prior expert professional, scientific and technical advice. -

![Or Later, but Before 1650] 687X868mm. Copper Engraving On](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3632/or-later-but-before-1650-687x868mm-copper-engraving-on-163632.webp)

Or Later, but Before 1650] 687X868mm. Copper Engraving On

60 Willem Janszoon BLAEU (1571-1638). Pascaarte van alle de Zécuften van EUROPA. Nieulycx befchreven door Willem Ianfs. Blaw. Men vintfe te coop tot Amsterdam, Op't Water inde vergulde Sonnewÿser. [Amsterdam, 1621 or later, but before 1650] 687x868mm. Copper engraving on parchment, coloured by a contemporary hand. Cropped, as usual, on the neat line, to the right cut about 5mm into the printed area. The imprint is on places somewhat weaker and /or ink has been faded out. One small hole (1,7x1,4cm.) in lower part, inland of Russia. As often, the parchment is wavy, with light water staining, usual staining and surface dust. First state of two. The title and imprint appear in a cartouche, crowned by the printer's mark of Willem Jansz Blaeu [INDEFESSVS AGENDO], at the center of the lower border. Scale cartouches appear in four corners of the chart, and richly decorated coats of arms have been engraved in the interior. The chart is oriented to the west. It shows the seacoasts of Europe from Novaya Zemlya and the Gulf of Sydra in the east, and the Azores and the west coast of Greenland in the west. In the north the chart extends to the northern coast of Spitsbergen, and in the south to the Canary Islands. The eastern part of the Mediterranean id included in the North African interior. The chart is printed on parchment and coloured by a contemporary hand. The colours red and green and blue still present, other colours faded. An intriguing line in green colour, 34 cm long and about 3mm bold is running offshore the Norwegian coast all the way south of Greenland, and closely following Tara Polar Arctic Circle ! Blaeu's chart greatly influenced other Amsterdam publisher's. -

Australian Nursing Federation – Registered Nurses, Midwives

2021 WAIRC 00144 WA HEALTH SYSTEM - AUSTRALIAN NURSING FEDERATION - REGISTERED NURSES, MIDWIVES, ENROLLED (MENTAL HEALTH) AND ENROLLED (MOTHERCRAFT) NURSES - INDUSTRIAL AGREEMENT 2020 WESTERN AUSTRALIAN INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS COMMISSION PARTIES NORTH METROPOLITAN HEALTH SERVICE, CHILD AND ADOLESCENT HEALTH SERVICE, EAST METROPOLITAN HEALTH SERVICE & OTHERS APPLICANTS -v- AUSTRALIAN NURSING FEDERATION, INDUSTRIAL UNION OF WORKERS PERTH RESPONDENT CORAM COMMISSIONER T EMMANUEL DATE MONDAY, 24 MAY 2021 FILE NO/S AG 8 OF 2021 CITATION NO. 2021 WAIRC 00144 Result Agreement registered Representation Applicants Mr L Martyr (as agent) Respondent Mr M Olson (as agent) Order HAVING heard from Mr L Martyr (as agent) on behalf of the applicants and Mr M Olson (as agent) on behalf of the respondent, the Commission, pursuant to the powers conferred under the Industrial Relations Act 1979 (WA), orders – THAT the agreement made between the parties filed in the Commission on 6 May 2021 entitled WA Health System – Australian Nursing Federation – Registered Nurses, Midwives, Enrolled (Mental Health) and Enrolled (Mothercraft) Nurses – Industrial Agreement 2020 attached hereto be registered as an industrial agreement in replacement of the WA Health System – Australian Nursing Federation – Registered Nurses, Midwives, Enrolled (Mental Health) and Enrolled (Mothercraft) Nurses - Industrial Agreement 2018 which by operation of s 41(8) is hereby cancelled. COMMISSIONER T EMMANUEL WA HEALTH SYSTEM – AUSTRALIAN NURSING FEDERATION – REGISTERED NURSES, MIDWIVES, ENROLLED (MENTAL HEALTH) AND ENROLLED (MOTHERCRAFT) NURSES – INDUSTRIAL AGREEMENT 2020 INDUSTRIAL AGREEMENT NO: AG 8 OF 2021 PART 1 – APPLICATION & OPERATION OF AGREEMENT 1. TITLE This Agreement will be known as the WA Health System – Australian Nursing Federation – Registered Nurses, Midwives, Enrolled (Mental Health) and Enrolled (Mothercraft) Nurses – Industrial Agreement 2020. -

Performance Evaluation of the 19Th Century Clipper Ship Cutty Sark: a Comparative Study

Performance Evaluation of the 19th Century Clipper Ship Cutty Sark: A Comparative Study C. Tonry1, M. Patel1, C. Bailey1, W. Davies2, J. Harrap2, E. Kentley2, P. Mason2 1University of Greenwich, London, UK 2 Abstract The Cutty Sark, built in 1869 in Dumbarton, is the last intact composite tea clipper ship [1]. One of the last tea clippers built she took part in the tea races back from China. These races caught the public imagination of the day and were widely reported in newspapers [2]. They developed from a desire for 'fresh' tea and the first ship to return with the new season's tea could charge a higher price for the cargo. Clipper ships were built for speed rather than carrying capacity. The hull efficiency of the Cutty Sark and her contemporaries is currently unknown. However, with modern CFD techniques, virtual experiments can be performed to model the fluid flow past the hull and so based on the shear stress and the pressure over the surface of the hull to calculate the resistance. In order to compare the hull against other ships three other ships were selected. The Farquharson, an East Indiaman built in 1820 [3]; the Thermopylae, another composite clipper built in 1868 which famously raced the Cutty Sark in 1872 [1]; and finally the Erasmo a later Italian all-steel construction 4-masted barque built in 1903[4]. Fig. 1 shows images of these ships. As only one of these ships exists today, and she no longer sails, 3D geometries were constructed fromlines plans of the ships hulls. -

Hornblower's Ships

Names of Ships from the Hornblower Books. Introduction Hornblower’s biographer, C S Forester, wrote eleven books covering the most active and dramatic episodes of the life of his subject. In addition, he also wrote a Hornblower “Companion” and the so called three “lost” short stories. There were some years and activities in Hornblower’s life that were not written about before the biographer’s death and therefore not recorded. However, the books and stories that were published describe not only what Hornblower did and thought about his life and career but also mentioned in varying levels of detail the people and the ships that he encountered. Hornblower of course served on many ships but also fought with and against them, captured them, sank them or protected them besides just being aware of them. Of all the ships mentioned, a handful of them would have been highly significant for him. The Indefatigable was the ship on which Midshipman and then Acting Lieutenant Hornblower mostly learnt and developed his skills as a seaman and as a fighting man. This learning continued with his experiences on the Renown as a lieutenant. His first commands, apart from prizes taken, were on the Hotspur and the Atropos. Later as a full captain, he took the Lydia round the Horn to the Pacific coast of South America and his first and only captaincy of a ship of the line was on the Sutherland. He first flew his own flag on the Nonsuch and sailed to the Baltic on her. In later years his ships were smaller as befitted the nature of the tasks that fell to him. -

The Ninth Issue of Ngari Capes Marine Park News

Ngari Capes Newsletter Page 1 of 17 Issue 9 - Autumn 2021 Welcome to the ninth issue of Ngari Capes Marine Park News In this issue: • Introducing District Manager Wayne Elliott • The wreck of SS Pericles • Eight new angel rings installed within Ngari Capes • "Mutant" kelp found within the Ngari Capes Marine Park • 2021 Ngari Capes Seagrass Monitoring • Best science minds in underwater think tank • Do you know about marine park sanctuary zones? Above: Torpedo Rocks, Yallingup Introducing District Manager Wayne Elliott file:///C:/Users/NICOLE~1/AppData/Local/Temp/Low/WMCKOHD6.htm 27/04/2021 Ngari Capes Newsletter Page 2 of 17 I grew up in Cape Town, South Africa close enough to the Atlantic Ocean that on most mornings, I awoke to the sound of the waves in Table Bay. My earliest childhood memories were been stung by jellyfish everytime I swam in the ocean and just how cold the Atlantic Ocean was. Whilst at the University of Cape Town, I worked as a ranger at the Cape of Good Hope Nature Reserve. The reserve, now part of a larger national park was bounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the west and the Indian Ocean to the east which resulted in a very diverse marine environment. I had the privilege of monitoring the Black Oystercatcher population within a 7 km sanctuary zone and have fond memories of been the only person, apart from the baboons on the beach every day. In later years, I worked for a provincial conservation organisation in KwaZulu- Natal, much like DBCA and was responsible, amongst other duties, for the overall management of the many marine reserves. -

Ortelius's Typus Orbis Terrarum (1570)

Ortelius’s Typus Orbis Terrarum (1570) by Giorgio Mangani (Ancona, Italy) Paper presented at the 18th International Conference for the History of Cartography (Athens, 11-16th July 1999), in the "Theory Session", with Lucia Nuti (University of Pisa), Peter van der Krogt (University of Uthercht), Kess Zandvliet (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), presided by Dennis Reinhartz (University of Texas at Arlington). I tried to examine this map according to my recent studies dedicated to Abraham Ortelius,1 trying to verify the deep meaning that it could have in his work of geographer and intellectual, committed in a rather wide religious and political programme. Ortelius was considered, in the scientific and intellectual background of the XVIth century Low Countries, as a model of great morals in fact, he was one of the most famous personalities of Northern Europe; he was a scholar, a collector, a mystic, a publisher, a maps and books dealer and he was endowed with a particular charisma, which seems to have influenced the work of one of the best artist of the time, Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Dealing with the deep meaning of Ortelius’ atlas, I tried some other time to prove that the Theatrum, beyond its function of geographical documentation and succesfull publishing product, aimed at a political and theological project which Ortelius shared with the background of the Familist clandestine sect of Antwerp (the Family of Love). In short, the fundamentals of the familist thought focused on three main points: a) an accentuated sensibility towards a mysticism close to the so called devotio moderna, that is to say an inner spirituality searching for a direct relation with God. -

100 the SOUTH-WEST CORNER of QUEENSLAND. (By S

100 THE SOUTH-WEST CORNER OF QUEENSLAND. (By S. E. PEARSON). (Read at a meeting of the Historical Society of Queensland, August 27, 1937). On a clear day, looking westward across the channels of the Mulligan River from the gravelly tableland behind Annandale Homestead, in south western Queensland, one may discern a long low line of drift-top sandhills. Round more than half the skyline the rim of earth may be likened to the ocean. There is no break in any part of the horizon; not a landmark, not a tree. Should anyone chance to stand on those gravelly rises when the sun was peeping above the eastem skyline they would witness a scene that would carry the mind at once to the far-flung horizons of the Sahara. In the sunrise that western region is overhung by rose-tinted haze, and in the valleys lie the purple shadows that are peculiar to the waste places of the earth. Those naked, drift- top sanddunes beyond the Mulligan mark the limit of human occupation. Washed crimson by the rising sun they are set Kke gleaming fangs in the desert's jaws. The Explorers. The first white men to penetrate that line of sand- dunes, in south-western Queensland, were Captain Charles Sturt and his party, in September, 1845. They had crossed the stony country that lies between the Cooper and the Diamantina—afterwards known as Sturt's Stony Desert; and afterwards, by the way, occupied in 1880, as fair cattle-grazing country, by the Broad brothers of Sydney (Andrew and James) under the run name of Goyder's Lagoon—and the ex plorers actually crossed the latter watercourse with out knowing it to be a river, for in that vicinity Sturt describes it as "a great earthy plain." For forty miles one meets with black, sundried soil and dismal wilted polygonum bushes in a dry season, and forty miles of hock-deep mud, water, and flowering swamp-plants in a wet one. -

WA998 Houtman Abrolhos Easter Group

998 WA HOUTMAN ABROLHOS - EASTER GROUP EASTER - ABROLHOS HOUTMAN SEE RELATED PUBLICATIONS: Notice to Mariners (http://www.transport.wa.gov.au/imarine/coastaldata/), Symbols, Abbreviations DEPTHS IN METRES and Terms (INT 1), Tide Tables, Sailing Directions. For surveys beyond this chart refer to RAN Charts AUS 332 and AUS 751. E= 7 60 000 E= 7 68 000 E= 7 76 000 38' 39' 40' 41' 42' 43' 44' 113° E45' 46' 47' 48' 49' 50' 51' 52' 53' 54' 9 10 2 10 31 27 32 32 7 1 8 6 36 97 44 42 43 28° 30' 06" S 29 26 27 63 46 32 12 3 18 97 4 18 32 28 2 21 113° 45' E THE HOUTMAN ABROLHOS 9 3 21 39 1 5 6 37 5 6 5 40 28° 30' 06" S HOUTMAN ABROLHOS The Houtman Abrolhos and it's surrounding coral reef 32 4 4 175 38 20 2 22 communities form one of Western Australia's most unique marine 26 2 33 18 18 114 113° 54' 12" E areas. The islands' environments - both marine and terrestrial - 19 5 15 CHART LAYOUT are very fragile, and need the protection of residents and visitors 62 41 29 29 37 alike. 68 18 113° 54' 12" E 29 32 93 18 22 41 The Abrolhos is part of the aquatic heritage of all West Australians 4 34 29 24 17 40 -itis our task to ensure that we hand the islands, their fish stocks 8 99 31’ 94 124 8 12 43 31’ 39 4 32 42 and their wildlife onto future generations, undamaged and still 30 27 productive.