100 the SOUTH-WEST CORNER of QUEENSLAND. (By S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report to Office of Water Science, Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation, Brisbane

Lake Eyre Basin Springs Assessment Project Hydrogeology, cultural history and biological values of springs in the Barcaldine, Springvale and Flinders River supergroups, Galilee Basin and Tertiary springs of western Queensland 2016 Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation Prepared by R.J. Fensham, J.L. Silcock, B. Laffineur, H.J. MacDermott Queensland Herbarium Science Delivery Division Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation PO Box 5078 Brisbane QLD 4001 © The Commonwealth of Australia 2016 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence Under this licence you are free, without having to seek permission from DSITI or the Commonwealth, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the source of the publication. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5725 Citation Fensham, R.J., Silcock, J.L., Laffineur, B., MacDermott, H.J. -

DUCK HUNTING in VICTORIA 2020 Background

DUCK HUNTING IN VICTORIA 2020 Background The Wildlife (Game) Regulations 2012 provide for an annual duck season running from 3rd Saturday in March until the 2nd Monday in June in each year (80 days in 2020) and a 10 bird bag limit. Section 86 of the Wildlife Act 1975 enables the responsible Ministers to vary these arrangements. The Game Management Authority (GMA) is an independent statutory authority responsible for the regulation of game hunting in Victoria. Part of their statutory function is to make recommendations to the relevant Ministers (Agriculture and Environment) in relation to open and closed seasons, bag limits and declaring public and private land open or closed for hunting. A number of factors are reviewed each year to ensure duck hunting remains sustainable, including current and predicted environmental conditions such as habitat extent and duck population distribution, abundance and breeding. This review however, overlooks several reports and assessments which are intended for use in managing game and hunting which would offer a more complete picture of habitat, population, abundance and breeding, we will attempt to summarise some of these in this submission, these include: • 2019-20 Annual Waterfowl Quota Report to the Game Licensing Unit, New South Wales Department of Primary Industries • Assessment of Waterfowl Abundance and Wetland Condition in South- Eastern Australia, South Australian Department for Environment and Water • Victorian Summer waterbird Count, 2019, Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research As a key stakeholder representing 17,8011 members, Field & Game Australia Inc. (FGA) has been invited by GMA to participate in the Stakeholder Meeting and provide information to assist GMA brief the relevant Ministers, FGA thanks GMA for this opportunity. -

Birdsville Desert Escape

9 DAYS BIRDSVILLE DESERT ESCAPE colours in Welford National Park; golden Day 1 | WEDNESDAY | LONGREACH green spinifex, white-barked ghost Arrive in Longreach for the start of your TOUR HIGHLIGHTS gums and stunning red sand dunes. Late Outback Queensland adventure. You afternoon in Windorah, we’ll take a short Qantas Founders Museum will be met at either Longreach Railway trip out of town to toast the sunset from Australian Stockman’s Hall of Fame Station or Longreach Airport by your beautiful wind-swept red sandhills. Have Drover’s Sunset Cruise including Savannah Guides Operator driver and your cameras ready! Smithy’s Outback Dinner & Show host. Transfer to your accommodation for Overnight Cooper Cabins or Welford National Park a Welcome Supper and tour briefing. Western Star Hotel, Windorah Sunset Sandhill nibbles, Windorah 2 nights Albert Park Motor Inn, Longreach Betoota Ghost Town and Day 4 | SATURDAY | BIRDSVILLE JC Hotel Ruins See the JC Hotel Ruins, once part of the Day 2 | THURSDAY | LONGREACH Deon’s Lookout and Dreamtime Enjoy an orientation tour of Longreach old township site of Canterbury. Visit Serpent Art Sculpture then visit the world-class Qantas Founders Betoota, originally established to collect Sunset nibbles atop Big Red Museum, eloquently telling the story of the cattle tolls and later as a Cobb & Co change (Sand Dune) founding of Qantas. Discover the inspiring station. It’s now a ghost town. Take in Inland Hospital Ruins stories of our pioneering heroes at the spectacular views and enjoy a picnic lunch Channel Country Touring Australian Stockman’s Hall of Fame. Late at Deon’s Lookout. -

Australian Nursing Federation – Registered Nurses, Midwives

2021 WAIRC 00144 WA HEALTH SYSTEM - AUSTRALIAN NURSING FEDERATION - REGISTERED NURSES, MIDWIVES, ENROLLED (MENTAL HEALTH) AND ENROLLED (MOTHERCRAFT) NURSES - INDUSTRIAL AGREEMENT 2020 WESTERN AUSTRALIAN INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS COMMISSION PARTIES NORTH METROPOLITAN HEALTH SERVICE, CHILD AND ADOLESCENT HEALTH SERVICE, EAST METROPOLITAN HEALTH SERVICE & OTHERS APPLICANTS -v- AUSTRALIAN NURSING FEDERATION, INDUSTRIAL UNION OF WORKERS PERTH RESPONDENT CORAM COMMISSIONER T EMMANUEL DATE MONDAY, 24 MAY 2021 FILE NO/S AG 8 OF 2021 CITATION NO. 2021 WAIRC 00144 Result Agreement registered Representation Applicants Mr L Martyr (as agent) Respondent Mr M Olson (as agent) Order HAVING heard from Mr L Martyr (as agent) on behalf of the applicants and Mr M Olson (as agent) on behalf of the respondent, the Commission, pursuant to the powers conferred under the Industrial Relations Act 1979 (WA), orders – THAT the agreement made between the parties filed in the Commission on 6 May 2021 entitled WA Health System – Australian Nursing Federation – Registered Nurses, Midwives, Enrolled (Mental Health) and Enrolled (Mothercraft) Nurses – Industrial Agreement 2020 attached hereto be registered as an industrial agreement in replacement of the WA Health System – Australian Nursing Federation – Registered Nurses, Midwives, Enrolled (Mental Health) and Enrolled (Mothercraft) Nurses - Industrial Agreement 2018 which by operation of s 41(8) is hereby cancelled. COMMISSIONER T EMMANUEL WA HEALTH SYSTEM – AUSTRALIAN NURSING FEDERATION – REGISTERED NURSES, MIDWIVES, ENROLLED (MENTAL HEALTH) AND ENROLLED (MOTHERCRAFT) NURSES – INDUSTRIAL AGREEMENT 2020 INDUSTRIAL AGREEMENT NO: AG 8 OF 2021 PART 1 – APPLICATION & OPERATION OF AGREEMENT 1. TITLE This Agreement will be known as the WA Health System – Australian Nursing Federation – Registered Nurses, Midwives, Enrolled (Mental Health) and Enrolled (Mothercraft) Nurses – Industrial Agreement 2020. -

Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks

Department for Environment and Heritage Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks Part of the Far North & Far West Region (Region 13) Historical Research Pty Ltd Adelaide in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd Lyn Leader-Elliott Iris Iwanicki December 2002 Frontispiece Woolshed, Cordillo Downs Station (SHP:009) The Birdsville & Strzelecki Tracks Heritage Survey was financed by the South Australian Government (through the State Heritage Fund) and the Commonwealth of Australia (through the Australian Heritage Commission). It was carried out by heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd, in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd, Lyn Leader-Elliott and Iris Iwanicki between April 2001 and December 2002. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia and they do not accept responsibility for any advice or information in relation to this material. All recommendations are the opinions of the heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd (or their subconsultants) and may not necessarily be acted upon by the State Heritage Authority or the Australian Heritage Commission. Information presented in this document may be copied for non-commercial purposes including for personal or educational uses. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires written permission from the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to either the Manager, Heritage Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001, or email [email protected], or the Manager, Copyright Services, Info Access, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601, or email [email protected]. -

Innamincka Regional Reserve About

<iframe src="https://www.googletagmanager.com/ns.html?id=GTM-5L9VKK" height="0" width="0" style="display:none;visibility:hidden"></iframe> Innamincka Regional Reserve About Check the latest Desert Parks Bulletin (https://cdn.environment.sa.gov.au/parks/docs/desert-parks-bulletin- 21092021.pdf) before visiting this park. Innamincka Regional Reserve is a park of contrasts. Covering more than 1.3 million hectares of land, ranging from the life-giving wetlands of the Cooper Creek system to the stark arid outback, the reserve also sustains a large commercial beef cattle enterprise, and oil and gas fields. The heritage-listed Innamincka Regional Reserve park headquarters and interpretation centre gives an insight into the natural history of the area, Aboriginal people, European settlement and Australia's most famous explorers, Burke and Wills. From the interpretation centre, visit the sites where Burke and Wills died, and the historic Dig Tree site (QLD) which once played a significant part in their ill-fated expedition. Shaded by the gums, the waterholes provide a relaxing place for a spot of fishing or explore the creek further by canoe or boat. Opening hours Open daily. Fire safety and information Listen to your local area radio station (https://www.cfs.sa.gov.au/public/download.jsp?id=104478) for the latest updates and information on fire safety. Check the CFS website (https://www.cfs.sa.gov.au/site/home.jsp) or call the CFS Bushfire Information Hotline 1800 362 361 for: Information on fire bans and current fire danger ratings (https://www.cfs.sa.gov.au/site/bans_and_ratings.jsp) Current CFS warnings and incidents (https://www.cfs.sa.gov.au/site/warnings_and_incidents.jsp) Information on what to do in the event of a fire (https://www.cfs.sa.gov.au/site/prepare_for_a_fire.jsp) Please refer to the latest Desert Parks Bulletin (https://cdn.environment.sa.gov.au/parks/docs/desert-parks-bulletin- 21092021.pdf) for current access and road condition information. -

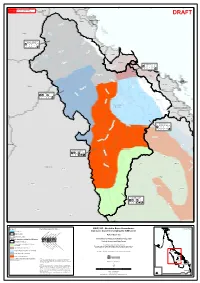

GWQ1203 - Burdekin Basin Groundwater Location Map Watercourse Cainozoic Deposits Overlying the GAB Zones

144°0'0"E 145°0'0"E 146°0'0"E 147°0'0"E 148°0'0"E 149°0'0"E Tully 18°0'0"S This map must not be used for marine navigation. 18°0'0"S Comprehensive and updated navigation WARNING information should be obtained from published Mitchell hydrographic charts. Murray DRAFT Hinchinbrook Island Herbert r ve Ri ekin urd B Ingham ! er iv D R ry Gilbert ry Ri D v er r e iv 19°0'0"S Scattered Remnants Northern R 19°0'0"S g Burdekin Headwaters in n n R u Black Townsville ! er r iv e R v rke i la R C r ta S Ross Broken River Ayr ! er ver Riv i ry lt R Haughton go Basa e r Don and Bogie Coastal Area G h t r u ve o i ton R S h ug Ha Bowen ! 20°0'0"S 20°0'0"S r Charters Towers e v ! i Don R B n o o g i D e Riv er Bur dek in R ive r Whitsunday Island Proserpine B owe Proserpine Flinders n ! er R Riv iver e sp a R amp C o Don River l l s to n R iv C e a r North West Suttor Catchment pe R r iv ve e i r R r o t t u S r e Broken v R i iv S e R e r llh L e e i O'Connell p im t t a l R e C iv er B o w e B u r d ekin n B u r d ekin R 21°0'0"S i 21°0'0"S v e BB a a s s in in r B ro Mackay ke ! n River Pioneer Plane Sarina ! Eastern Weathered Su ttor R Cainozoic Remnants Belyandor River iv e er iv R o d n lya e B r e v i R o d Moranbah n ! a ly 22°0'0"S e 22°0'0"S l R B ae iver ich Carm r ive R Diamantina s r o n n o C Styx Belyando River Saline Tertiary Sediments Dysart ! Is a a c R iv B Clermont Middlemount er e ! ! l y an do Riv e r er iv Cooper Creek R ie nz Aramac e ! k c a M 23°0'0"S 23°0'0"S Capella -

Innamincka/Cooper Creek State Heritage Area Innamincka/Cooper Creek Was Declared a State Heritage Area on 16 May 1985

Innamincka/Cooper Creek State Heritage Area Innamincka/Cooper Creek was declared a State Heritage Area on 16 May 1985. HISTORY Innamincka and Cooper Creek have a rich history. The area has also been associated with many other facets of the state's history since colonial settlement. Names such as Charles Sturt, Sidney Kidman, Cordillo Downs, the Australian Inland Mission and the Reverend John Flynn are intrinsically woven into the stories of Innamincka and the Cooper Creek. Its significance for Aboriginal people spans thousands of years as a trade route and a source of abundant food and fresh water. The area's Aboriginal history also includes significant contacts with explorers, pastoralists and settlers. Many sources believe that the name 'Innamincka' comes from two Aboriginal words meaning ' your shelter' or 'your home'. European contact with the region came first with the explorers and later with the establishment of the pastoral industry, transport routes and service centres. Cooper Creek was named by Captain Charles Sturt on 13 October 1845, when he crossed the watercourse at a point approximately 24 kilometres west of the current Innamincka township. The water was very low at the time, hence his use of the term 'creek' rather than 'river' to describe what often becomes a deep torrent of water. Charles Cooper, after whom the waterway was named, was a South Australian judge - later Chief Justice Sir Charles Cooper. On the same expedition, Sturt also named the Strzelecki Desert after the eccentric Polish explorer, Paul Edmund de Strzelecki, who was the first European to climb and name Mount Kosciusko. -

Into Queensland, to Within 45 Km of the Georgina River Floodout Complex

into Queensland, to within 45 km of the Georgina River floodout complex. As a consequence, it is correctly included in the Georgina Basin. There is one river of moderate size in the Georgina basin that does not connect to any of the major rivers and that is Lucy Creek, which runs east from the Dulcie Ranges and may once have connected to the Georgina via Manners Creek. Table 7. Summary statistics of the major rivers and creeks in Lake Eyre Drainage Division Drainage Major Tributaries Initial Interim Highest Point Height of Lowest Straight System Bioregion & in Catchment highest Point Line Terminal (m asl) Major in NT Length Bioregions Channel (m asl) (km) (m asl) Finke River Basin: Finke R. Hugh R., Palmer R., MAC FIN, STP, 1,389 700 130 450† Karinga Ck., SSD Mt Giles Coglin Ck. Todd River Basin: Todd R. Ross R. BRT MAC, SSD 1,164 625 220 200 Mt Laughlin Hale R. Cleary Ck., Pulya Ck. MAC SSD 1,203 660 200 225 Mt Brassey Illogwa Ck. Albarta Ck. MAC BRT, SSD 853 500 230 140 Mt Ruby Hay River Basin: Plenty R. Huckitta Ck., Atula MAC BRT, SSD 1,203 600 130 270 Ck., Marshall R. Mt Brassey Corkwood (+ Hay R.) Bore Hay R. Marshall R., Arthur MAC, BRT, SSD 594 440 Marshal 70 355 Ck. (+ Plenty R.) CHC 340 Arthur Georgina River Basin: Georgina R. Ranken R., James R., MGD, CHC, SSD 220 215 190 >215 † (?Sandover R.) (?BRT) Sandover R. Mueller Ck., Waite MAC, BRT, BRT, 996 550 260 270 Ck., Bundey R., CHC, DAV CHC, Bold Hill Ooratippra Ck. -

Cowarie Station Hasn't Seen a Flood Since 2011, and a New Generation

STATIONS The Oldfields are focused on cleaning up their core herd of Shorthorn/Santa Gertrudis composites. RIDING THE INLAND TIDE Cowarie Station hasn’t seen a flood since 2011, and a new generation is standing by ready to make a splash. STORY GRETEL SNEATH PHOTOS ROBERT LANG STATIONS he chopper cuts through cobalt sky, bringing news like a carrier pigeon. Craig Oldfield leaps from the cockpit onto the sunburnt soil of Cowarie Station with the T message his family has been waiting to hear for seven long years: “The floodwaters are coming!” Higher up the Birdsville Track, the behemoth to see; when that flood’s coming and you know the Clifton Hills Station has been inundated with water potential of it, it just makes you smile.” that began as a record-breaking deluge of rain over Craig’s mother, Sharon Oldfield, flies up in a fixed- Winton in Queensland eight weeks prior. Slowly it’s wing Piper Lance aircraft the following day to see the snaking down the Diamantina River into Goyder spectacle, and shares her eldest son’s joy. She used to Lagoon, the Warburton Creek and, eventually, Lake tell her children that mirages were magic puddles, but Eyre. It’s a sight to behold as it generously spills this is the real deal. The magic lies with nature. “It’s far beyond the channels, across the gibber plains of like veins bringing the country to life,” she says. “In two Sturt Stony Desert and the sandy Simpson Desert, weeks’ time, this will all be green.” sending a saturating lifeline to the long-suffering Seen from 1000 feet above, the headwaters are easy outback landscape. -

NAP3.119 Final Report

final report Project Code: NAP3.119 Prepared by: NT Department of Primary Industries, Fisheries and Mines Date published: June 2007 ISBN: 9781741911282 PUBLISHED BY Meat and Livestock Australia Limited Locked Bag 991 NORTH SYDNEY NSW 2059 Lake Nash Breeder Herd Efficiency Project Meat & Livestock Australia acknowledges the matching funds provided by the Australian Government to support the research and development detailed in this publication. This publication is published by Meat & Livestock Australia Limited ABN 39 081 678 364 (MLA). Care is taken to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this publication. However MLA cannot accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information or opinions contained in the publication. You should make your own enquiries before making decisions concerning your interests. Reproduction in whole or in part of this publication is prohibited without prior written consent of MLA. Lake Nash Breeder Herd Efficiency Project Abstract This study involved monitoring both breeder cow performance and pasture quality on the Barkly Tableland. It was designed to provide producers in the region with practical strategies to evaluate both livestock and pasture performance over a wide range of seasonal conditions. The study was able to highlight the losses that may be occurring annually between pregnancy diagnosis and weaning (approx 17%), and the pasture sampling techniques employed (NIRS) will be of great benefit to producers who wish to target their supplementation programs. The significance of the more common reproductive diseases in the regions has been documented and the beef industry will be confident in the management and expenditure on control programmes for these diseases – especially on the Barkly Tableland. -

Prairie Hotel William Creek Birdsville Innamincka

SIMPSON DESERT BOULIA NATIONAL WADDI IAMANTINA R QUEENSLAND C D RIVE PARK TREES NAPPANERICA SAND DUNE DEON’S (BIG RED) BETOOTA LOOKOUT TO BRISBANE POEPPEL CORNER QUEENSLAND DREAMTIME SERPENT TO KULGERA WITJIRA INE (Corner of SA, via FINKE H L BIRDSVILLE SOUTH AUSTRALIA HADDON CORNER MT DARE NATIONAL PARK FRENC QLD and NT) C ERINGA WATERHOLE O SIMPSON DESERT R (Stuart Campsite) A K D C REGIONAL RESERVE I RALIA A L O R L L DALHOUSIE SPRINGS T O D G E D H I D O A S N N W QUEENSLAND I D R E N A O L S SOUTH AUST U IL O T V GOYDER’S R R E S O A Y B D D LAGOON R R U I B B ALICE SPRINGS & ULURU (AYERS ROCK) A R SIMPSON DESERT R A MARLA INNAMINCKA W A REGIONAL L K RESERVE E R S D COONGIE LAKES S STURT OODNADATTA C T K R U E LLO STONY E O BURKE BU AL RD A MENT R S VELOP R G DESERT C S & WILLS DE T IN R G DIG TREE H E I THE PAINTED DESERT P INNAMINCKA G O H O KINGS MARKER W C BURKES GRAVE SITE A COPPER HILLS Y WILLS GRAVE SITE TO ALGEBUCKINA BRIDGE THARGOMINDAH AND WATERHOLE MUNGERANNIE E INNAMINCKA ROADHOUSE HOTEL ADVENTURE WAY CONNECTING F COAST WITH THE OUTBACK RANIE TTE K LAKE EYRE NATIONAL PARK NA SA ND C H A IL LAKE EYRE L R BETHESDA MISSION S STRZELECKI T O NORTH (1867 - 1917) I L DESERT K H D MOON PLAIN C G E H K OP AN C STRZELECKI L A THE BREAKAWAYS RESERVE R E L F OU A I T R REGIONAL Z EL E T D I E RESERVE R S OP L T AL L FI I S EL V D S COOBER PEDY S WILLIAM CREEK D BLE R COB I SA B ND LAKE H CAMERON CORNER IRRAPATANA SANDHILLS IL LAKE EYRE L O (Corner of QLD, J BLANCHE S P SOUTH CLAYTON WETLANDS NSW and SA) A COWARD CURDIMURKA L K MONTECOLLINA