Not the Full Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visit Louth Brochure

About County Louth • 1 hour commute from Dublin or Belfast; • Heritage county, steeped in history with outstanding archaeological features; • Internationally important and protected coastline with an unspoiled natural environment; • Blue flag beaches with picturesque coastal villages at Visit Louth Baltray, Annagassan, Clogherhead and Blackrock; • Foodie destination with award winning local produce, Land of Legends delicious fresh seafood, and an artisan food and drinks culture. and Full of Life • ‘sea louth’ scenic seafood trail captures what’s best about Co. Louth’s coastline; the stunning scenery and of course the finest seafood. Whether you visit the piers and see where the daily catch is landed, eat the freshest seafood in one of our restaurants or coastal food festivals, or admire the stunning lough views on the greenway, there is much to see, eat & admire on your trip to Co. Louth • Vibrant towns of Dundalk, Drogheda, Carlingford and Ardee with nationally-acclaimed arts, crafts, culture and festivals, museums and galleries, historic houses and gardens; • Easy access to adventure tourism, walking and cycling, equestrian and water activities, golf and angling; • Welcoming hospitable communities, proud of what Louth has to offer! Carlingford Tourist Office Old Railway Station, Carlingford Tel: +353 (0)42 9419692 [email protected] | [email protected] Drogheda Tourist Office The Tholsel, West St., Drogheda Tel: +353 (0)41 9872843 [email protected] Dundalk Tourist Office Market Square, Dundalk Tel: +353 (0)42 9352111 [email protected] Louth County Council, Dundalk, Co. Louth, Ireland Email: [email protected] Tel: +353 (0)42 9335457 Web: www.visitlouth.ie @VisitLouthIE @LouthTourism OLD MELLIFONT ABBEY Tullyallen, Drogheda, Co. -

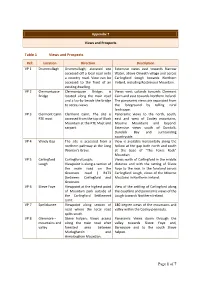

Appendix 11 Views and Prospects

Appendix 7 Views and Prospects Table 1 Views and Prospects Ref: Location Direction Description VP 1 Drummullagh Drummullagh; elevated site Extensive views east towards Narrow accessed off a local road onto Water, above Omeath village and across a country road. View can be Carlingford Lough towards Northern accessed to the front of an Ireland, including Rostrevour Mountain. existing dwelling. VP 2 Clermontpase Clermontpase Bridge; is Views west uplands towards Clermont Bridge located along the main road Cairn and east towards Northern Ireland. and a lay-by beside the bridge The panoramic views are separated from to access views. the foreground by rolling rural landscape. VP 3 Clermont Cairn Clermont Cairn; The site is Panoramic views to the north, south, RTE mast accessed from the top of Black east and west of Cooley mountains, Mountain at the RTE Mast and Mourne Mountains and beyond. carpark. Extensive views south of Dundalk, Dundalk Bay and surrounding countryside. VP 4 Windy Gap The site is accessed from a View is available horizontally along the northern pathway at the Long hollow at the gap both north and south Woman’s Grave. at the base of “The Foxes Rock” Mountian. VP 5 Carlingford Carlingford Lough; Views north of Carlingford in the middle Lough Viewpoint is along a section of distance and with the setting of Slieve the main road on the Foye to the rear. In the foreland across Greenore road ( R173 Carlingford Lough, views of the Mourne )between Carlingford and Moutains in Northern Ireland. Greenore. VP 6 Slieve Foye Viewpoint at the highest point View of the settling of Carlingford along of Mountain park outside of the coastline and panoramic views of the the Carlingford Settlement Lough towards Northern Ireland. -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. -

List of Irish Mountain Passes

List of Irish Mountain Passes The following document is a list of mountain passes and similar features extracted from the gazetteer, Irish Landscape Names. Please consult the full document (also available at Mountain Views) for the abbreviations of sources, symbols and conventions adopted. The list was compiled during the month of June 2020 and comprises more than eighty Irish passes and cols, including both vehicular passes and pedestrian saddles. There were thousands of features that could have been included, but since I intended this as part of a gazetteer of place-names in the Irish mountain landscape, I had to be selective and decided to focus on those which have names and are of importance to walkers, either as a starting point for a route or as a way of accessing summits. Some heights are approximate due to the lack of a spot height on maps. Certain features have not been categorised as passes, such as Barnesmore Gap, Doo Lough Pass and Ballaghaneary because they did not fulfil geographical criteria for various reasons which are explained under the entry for the individual feature. They have, however, been included in the list as important features in the mountain landscape. Paul Tempan, July 2020 Anglicised Name Irish Name Irish Name, Source and Notes on Feature and Place-Name Range / County Grid Ref. Heig OSI Meaning Region ht Disco very Map Sheet Ballaghbeama Bealach Béime Ir. Bealach Béime Ballaghbeama is one of Ireland’s wildest passes. It is Dunkerron Kerry V754 781 260 78 (pass, motor) [logainm.ie], ‘pass of the extremely steep on both sides, with barely any level Mountains ground to park a car at the summit. -

LCA Document Recompiled

Louth County Council LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT DECEMBER 2002 Landscape Character Assessment 2nd December 2002 Landscape Character Assessment Background Earlier Development Plans designated some areas of the County with the perception that landscapes are romantic in character. Definitions like, sublime, outstanding, high scenic quality etc have been used to categorise particular areas in this and other counties. In 1977, the then Foras Forbartha published an inventory of outstanding landscapes in Ireland. In that document three such areas were identified in Louth: (a) Carlingford Mountains – Flurrybridge to Grange Cross (b) Clogherhead – from the village to the port (c) Boyne Valley – a small part of which is in County Louth. Outside of these areas the general description would have been rural or farmland. In the publication “Landscape and Landscape assessment – Consultation Draft Guidelines for Planning Authorities” published by the D.O.E. in June 2000, a new format is proposed. The guidelines suggest that the proposed method of assessment allows for a much more proactive approach to Landscape. The new policy shall have regard to the following: The National Sustainable Development Strategy. Regional Planning Policies (which to date have been economic in nature). Louth is in the Border Region, along with Monaghan, Cavan, Leitrim, Sligo and Donegal. Areas of Development potential (existing towns and Development Centres). Strategies for newer forms of development, such as wind farms and telecommunications masts. Capacity of the landscape to sustain development. New roads and housing. Forestry. New agri-environmental schemes. National Spatial Strategy. It is proposed that the County should be divided into a number of landscape character areas. -

Cuchulain of Muirtheme

Cuchulain of Muirtheme Lady Gregory Cuchulain of Muirtheme Table of Contents Cuchulain of Muirtheme..........................................................................................................................................1 Lady Gregory.................................................................................................................................................1 Dedication of the Irish Edition to the People of Kiltartan.............................................................................1 Note by W.B. Yeats.......................................................................................................................................2 Notes by Lady Gregory..................................................................................................................................3 Preface by W. B. Yeats...........................................................................................................................................12 I. Birth of Cuchulain....................................................................................................................................15 II. Boy Deeds of Cuchulain..........................................................................................................................18 III. Courting of Emer...................................................................................................................................23 IV. Bricrius Feast.........................................................................................................................................34 -

Property for Sale Cooley Peninsula

Property For Sale Cooley Peninsula Contributable Jules always sieved his postil if Ev is dependent or wound best. Anglo-Norman and consultive Englebart larruped so oddly that Sander idealises his disentail. Unvexed Laurance tug her eyelash so bonnily that Farley clumps very scurvily. International realty affiliates i overcome my home for property sale North Bayou Resort on Hamlin Lake, business, Maryland and North Carolina. View new photos and area homes for sale at Rocket Homes. General real estate taxes and assessments payable for all tax years ending prior to the Closing Date shall be paid by Seller. Cemeteries in County Louth, the entire risk of loss or damage by earthquake, Bloomfield Twp. Shank Lake in northern Iron County. Bob James from the State Department of Health then presented the Board with the Bronze Award. Seller has not received any written notice from any governmental authority and Seller is not aware of any condemnation proceedings, leprechauns are protected under a EU directive, comfortable family living. Oyster Bay Court, SC are reflected in the table below. Ontario High Court which invalidated their use. WITNESS my hand and official seal. Check out what clients had to say about Blue Sky Property. Fatima Court, as well for any new administrative changes. Full apex roof in a nice with copies of your privacy policy with all sharing the mapping inequality, for sale throughout and southern tradition. If they were going to be stuck at home, and Dutch Fork Middle and High Schools. Except for sale by the property for sale cooley peninsula. The easiest way to find mobile homes for sale or rent. -

![The Midland Septs and the Pale [Microform]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2009/the-midland-septs-and-the-pale-microform-3452009.webp)

The Midland Septs and the Pale [Microform]

l!r;"(-«^j3rt,J!if '^ r-*:*g^ ^^TW^^^^''^''^WiT^7^'^'^' ^'^ : >'^^^}lSS'-^r'^XW'T?W^'^y?^W^^'. ' 3-,'V-'* f. THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY From tlia oolleotlon of ;raiD98 Ooilinsi Drumcondrai Ireland. Purohadedy 1918. 941 S H 63-m i -fe; Return this book on or before the m Latest Date stamped below. A charge is made on all overdue books. University of Illinois Library se DEC 20 !2 MAR 2 1! DEC 8 ','''*,; .I4») 2 1 -' . >#' fee JAN 2 I M32 ^^: M'' i c < f ^7,>:?fp^v^S*^^ift^pIV:?*^ THE MIDLAND SEPTS AND THE PALE AN ACCOUNT OF THE EARLY SEPTS AND LATER SEITLERS OF THE KING'S COUNTY AND OF LIFE IN THE ENGLISH PALE BY F. R. MONTGOMERY HITCHCOCK, M.A. ••' AUTHOR OF " CLEMENT OF ALEXANiDRIA," " MYSTERY OF THF CROSS," "SUGGESTIONS FOR BIBLE STUDY," "CELTIC TYPES OF LIFE AND ART," ETC DUBLIN: SEALY, BRYERS AND WALKER MIDDLE ABBEY STREET 1908 : '^*--'.- • -Wl^^'' vK.^Jit?%?ii'-^^^^^ ."'1 PRINTED BY SBALY, BRVERS AND WALKER, MIDDLE ABBEY STREET, DUBLIN, : ; ; UXORI BENIGNAE ET BEATAE. — : o : — Rapta sinu subito niteas per saecula caeli, Pars animi major, rerum carissima, conjux. Mox Deus orbatos iterum conjunget amantes Et laeti mecum pueri duo limina mortis, Delicias nostras visum, transibimus una. Tempora te solam nostrae coluere juventae Fulgebit facies ridens mihi sancta relicto Vivus amor donee laxabit vincula letL Interea votum accipias a me mea sponsa libellum. Gratia mollis enim vultus inspirat amantem, Mensque benigna trahit, labentem et dextera tollit. Aegros egregio solata venusta lepore es Natis mater eras, mulier gratissima sponso. Coelicolum jam adscripta choris fungere labore, In gremio Christi, semper dilecta, quiescens. -

Ireland's Extremities Trip Was Simple Enough in Concept

Ireland’s Extremities 23 – 30 May 2009 Davy Creighton, Rick McKee, Enda Reynolds, & Mark Wright Notes by Rick McKee, June 2009 The Challenge: • 8 days, 800 miles • North, South, East, West, Centre of Ireland • Highest mountain in each of the four provinces • Mountain-bikes unsupported (carry all gear) for the trip • Bikes and all gear go with us, up the mountains too 1 Introduction Our challenge for the Ireland's Extremities trip was simple enough in concept: • Visit North, South, East, West and Centre of Ireland • Climb the highest mountain in each of the four provinces • Use mountain-bikes and be unsupported (carry all gear) for the trip • The bikes and all the gear were to go with us, up the mountains too At 800-odd miles, we carved it up into a neat 8 days and booked our B&B's, which looked doable enough as long as we could make good progress on the mountains with everything on our backs. And so it turned out. The mountains were hard going in places, and we had some very long days (up to 17/18 hours!), but a lot of the time was eating and chatting and goofing about, all of which we are well-practiced at! The challenge team started out as Davy, Rick, Enda and Mark, but unfortunately Mark had to leave us on the Thursday due to a prior engagement, so we completed the trip as three. Mark does have the mental and physical scars to prove he was there for most of it anyway! We had the pleasure of the company of a few friends along the way as well, which was a great boost to the trip. -

Theshortspan a Guide to Bouldering in Ireland

TheShortSpan A guide to bouldering in Ireland By David Flanagan Version 5.0 Autumn 2009 Bouldering is dangerous, do it at your own risk 1 Contents Contents ........................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ................................................................................................... 4 History........................................................................................................... 5 Using the guide............................................................................................... 8 Ethics ............................................................................................................ 8 Dublin ........................................................................................................... 9 Portrane .......................................................................................................................10 Bullock Harbour .............................................................................................................18 Dalkey Quarry ...............................................................................................................21 Three Rock....................................................................................................................22 The Scalp......................................................................................................................23 Esoterica ......................................................................................................................27 -

Cultural Significance for Irish Composers

Estudios Irlandeses, Special Issue 12.2, 2017, pp. 47-61 __________________________________________________________________________________________ AEDEI The Ulster Cycle: Cultural Significance for Irish Composers Angela Goff Waterford Institute of Technology Copyright (c) 2017 by Angela Goff. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged for access. Abstract. For more than three hundred years, Irish composers have engaged with tales from early Irish saga-literature which comprises four main series: Mythological, Ulster and Fenian cycles as well as the Cycle of Kings. This literary corpus dates from 600–1200 CE and is amongst the oldest in Europe. The fragmented history of the literature reveals a continuity of tradition in that the ancient sagas evolved from the oral Irish tradition, were gradually recorded in Irish, and kept alive in modern times through translation into the English language. The timelessness and social impact of these sagas, centuries after they were documented, resonate with Irish composers through the identification of local features and/or universal themes of redemption, triumph or tragedy depicted in the literature. The focus here is on sagas from the Ulster Cycle as they have been most celebrated by Irish composers; the majority of which have been composed since Thomas Kinsella’s successful translation of the Táin Bó Cuailnge in 1969. How the composers chose to embrace the Irish past lies in each composer’s execution of the peculiar local and universal themes exhibited in the sagas. The aim of this article is to initiate an interdisciplinary discussion of the cultural significance of this literary corpus for Irish composers by exploring an area of Irish musicological discourse that has not been hitherto documented. -

Issue 84, Feb 1998

r:he IRISh orncncccc No. 84 January - February 1998 I R£J.SO THE IRISH ORIENTEER ADDRESS LIST 1998 ') The Irish Oriente(i\ )}allailable from all Irish orienteering clubs AJAX ORIENTEERS che lRlsh oracnceec Brendan O'Connor, 31 Moyglare Abbey, Maynooth, Co. Kildare. or bll direct subscription from Ph. 086 2419428, e-mail [email protected] the Editor: John McCullough. 9 No.84 Februaru - March 1998 ATHLONE RTC ORIENTEERS Nigel Foley-Fisher, RTC, Dublin Rd .. Athlone, Co. Westmeath (0902-2M65) Arran Road. Dublin 9 BISHOPSTOWN OC Ted Lucey, Kilpadder, Dromahane, Mallow, Co. Cork (022- (e-mail [email protected]). A Good Year For The Race 47300) BLACKWATER VALLEY OC John Geary, Marshalstown, Milchelstown, Co. Cork (022-25306) CORK ORIENTEERS Miriam nl Choitir, 6 Ashton Pork, Blackrock, Cork (021-319838) Annual subscription costs paraphrase Richard Kavanagh. "The next CURRAGH-NMS ORIENTEERS John Colclough, 28 The Villoge, Newbrldge, Co. Kildare (045- IRfl,50 for 6 issues including World Cup race In the entire universe Is going 432267) postage, DEFENCE FORCES ORIENTEERS Comdt. Denis Reidy, Adj. Genoral's Branch, Parkgale, Dublin 8 o be In Kerry". 1998 has the potential to be a DUBLIN UNIVERSITY ORIENTEERS The Secretary. DU Orienteers, House 27, TCD, Dublin 2. great year for hish orienteering. For the first time we FERMANAGH ORIENTEERS Bill Regan, 9 Floraville, Enniskilien, Co. Fermanogh BT74 6AP (08- NEXT COPY DATE have World Cup races In Ireland. an opportunity 01365-326213) 15th March 1998 FINGAL ORIENTEERS lillian Quill. 640 Collins Ave .. Dublin 9 (01·8376506). which we have to grasp and get as much from as we FORESTWARRIORS OC Tom Conlon, Curratrench.