Report of the Eighth Session of the Coordination Committee on Multilateral Payments Arrangements and Monetary Co-Operation Among Developing Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

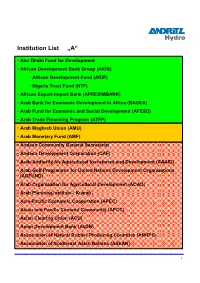

Institution List „A“

Institution List „A“ • Abu Dhabi Fund for Development • African Development Bank Group (AfDB) • African Development Fund (AfDF) • Nigeria Trust Fund (NTF) • African Export-Import Bank (AFREXIMBANK) • Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa (BADEA) • Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development (AFESD) • Arab Trade Financing Program (ATFP) • Arab Maghreb Union (AMU) • Arab Monetary Fund (AMF) • Andean Community General Secretariat • Andean Development Corporation (CAF) • Arab Authority for Agricultural Investment and Development (AAAID) • Arab Gulf Programme for United Nations Development Organizations (AGFUND) • Arab Organization for Agricultural Development (AOAD) • Arab Planning Institute - Kuwait • Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) • Asian and Pacific Coconut Community (APCC) • Asian Clearing Union (ACU) • Asian Development Bank (AsDB) • Association of Natural Rubber Producing Countries (ANRPC) • Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) 1 Institution List „B-C“ • Bank of Central African States (BEAC) • Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO) • Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) • Baltic Council of Ministers • Bank for International Settlements (BIS) • Black Sea Trade and Development Bank (BSTDB) • Caribbean Centre for Monetary Studies (CCMS) • Caribbean Community (CARICOM) • Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) • Caribbean Regional Technical Assistance Centre (CARTAC) • Center for Latin American Monetary Studies (CEMLA) • Center for Marketing Information and Advisory Services for Fishery Products -

Development of Payment and Settlement System

CHAPTER 7 Development of Payment and Settlement System Khin Thida Maw This chapter should be cited as: Khin Thida Maw, 2012. “Development of Payment and Settlement System.” In Economic Reforms in Myanmar: Pathways and Prospects, edited by Hank Lim and Yasuhiro Yamada, BRC Research Report No.10, Bangkok Research Center, IDE- JETRO, Bangkok, Thailand. Chapter 7 Development of Payment and Settlement System Khin Thida Maw ______________________________________________________________________ Abstract The new government of Myanmar has proved its intention to have good relations with the international community. Being a member of ASEAN, Myanmar has to prepare the requisite measures to assist in the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community in 2015. However, the legacy of the socialist era and the tight control on the banking system spurred people on to cash rather than the banking system for daily payment. The level of Myanmar’s banking sector development is further behind the standards of other regional banks. This paper utilizes a descriptive approach as it aims to provide the reader with an understanding of the current payment and settlement system of Myanmar’s financial sector and to recommend some policy issues for consideration. Section 1 introduces general background to the subject matter. Section 2 explains the existing domestic and international payment and settlement systems in use by Myanmar. Section 3 provides description of how the information has been collected and analyzed. Section 4 describes recent banking sector developments and points for further consideration relating to payment and settlement system. And Section 5 concludes with the suggestions and recommendation. ______________________________________________________________________ 1. Introduction Practically speaking, Myanmar’s economy was cash-based due to the prolonged decline of the banking system after nationalization beginning in the early 1960s. -

Introduction Establishment

ACU 1974 INTRODUCTION OBJECTIVES Secretary General settlement periods by a decision taken by unanimous vote of all of the Directors. Asian Clearing Union (ACU) is the simplest form of • To provide a facility to settle payments, on a multilateral The Board is authorized to appoint a Secretary General payment arrangements whereby the participants settle basis, for current international transactions among for a term of three years. The Secretary General may Interest payments for intra-regional transactions among the the territories of participants; be reappointed and shall cease to hold office when the Interest shall be paid by net debtors and transferred to participating central banks on a multilateral basis. The Board so decides. • To promote the use of participants’ currencies net creditors on daily outstandings between settlement main objectives of a clearing union are to facilitate in current transactions between their respective Agent dates. The rate of interest applicable for a settlement payments among member countries for eligible territories and thereby effect economies in the use period will be the closing rate on the first working day transactions, thereby economizing on the use of foreign The Board of Directors may make arrangements with of the participants’ exchange reserves; of the last week of the previous calendar month offered exchange reserves and transfer costs, as well as a central bank or monetary authority of a participant by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) for one promoting trade among the participating countries. The • To promote monetary cooperation among the to provide the necessary services and facilities for the month US dollar and Euro deposits. -

Toward a More Universal Currency: the Impact of the Clearing Mechanism on Developing Economies

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State Applied Economics Theses Economics and Finance 5-2019 Toward a More Universal Currency: The mpI act of the Clearing Mechanism on Developing Economies Evan Ross Kaderbeck State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College, [email protected] Advisor Dr. Ted Schmidt First Reader Dr. Ted Schmidt Second Reader Dr. Frederick Floss Third Reader Dr. Joelle LeClaire Department Chair Dr. Frederick Floss To learn more about the Economics and Finance Department and its educational programs, research, and resources, go to https://economics.buffalostate.edu/. Recommended Citation Kaderbeck, Evan Ross, "Toward a More Universal Currency: The mpI act of the Clearing Mechanism on Developing Economies" (2019). Applied Economics Theses. 40. https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/economics_theses/40 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/economics_theses Part of the Finance Commons, and the International Economics Commons Toward a More Universal Currency: The Impact of the Clearing Mechanism on Developing Economies by Evan Kaderbeck An Abstract of a Thesis in Applied Economics Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts May 2019 Buffalo State College State University of New York Department of Economics and Finance ii ABSTRACT OF THESIS Toward a More Universal Currency: The Impact of the Clearing Mechanism on Developing Economies As part of a broader plan to reform the system of international finance, experts have indicated the need to modify the system of international money. They point to problems such as the difficulties faced by developing countries in obtaining hard currency needed for imports, or the flows of hot money which make the financing of long-term development projects difficult. -

Duvvuri Subbarao: Currency Wars, Rural Development, Rising House Prices and the Deepening of Capital Markets

Duvvuri Subbarao: Currency wars, rural development, rising house prices and the deepening of capital markets Interview with Mr Duvvuri Subbarao, Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, published on ft.com/beyondbrics on 18 November 2010. * * * Currency wars and capital flows Rupee strength beyondbrics reader: Why is the RBI opposed to rupee appreciation? With billions of people, an increase in purchasing power enabled by a strong rupee could do wonders, rather than surrendering to handful of export industries. Since poverty is a serious problem in India, don’t you think a stronger rupee could help them? Duvvuri Subbarao: RBI is not opposed to appreciation or depreciation of the rupee. What RBI is typically concerned about is volatile movements in the exchange rate. Both large depreciation and appreciation could have significant costs, particularly in terms of inflation (with depreciation) and loss of external competitiveness (with appreciation). This is all the more so if appreciation, as in recent times, is due to volatile capital flows. The argument that a stronger currency has an anti-poverty impact by softening inflation is quite persuasive. However, the beneficial impact depends on the extent [to which] the exchange rate [passes] through to prices. Empirical research shows that, in the Indian context, the pass through is quite low – in the range of 0.4–0.9 per cent. Our exchange rate policy is not guided by a target or a band. Our policy has been to intervene in the market only to manage excessive volatility and prevent disruptions to the macroeconomic situation. QE2’s impact on India beyondbrics reader: How will the new US round of quantitative easing (QE2) affect India? Would you welcome it as a good source of cheap money to finance the infrastructure investments that India badly needs? DS: India needs to raise its investment by a quantum step if it has to realize its aspiration of a double digit growth. -

Regional Integration and Liberal Economic Order in SAARC: a Case Study of Trade Relations Between Pakistan and India Under SAFTA Regime (1997-2015)

Regional Integration and Liberal Economic order in SAARC: A Case Study of Trade Relations between Pakistan and India under SAFTA Regime (1997-2015) Sarfraz Batool Ph.D. (Political Science) Roll No. 04 Session: 2013-2018 Supervisor Prof. Dr. UMBREEN JAVAID Department of Political Science University of the Punjab Lahore. i Regional Integration and Liberal Economic order in SAARC: A Case Study of Trade Relations between Pakistan and India under SAFTA Regime (1997-2015) This thesis is submitted in Partial fulfilment of Ph.D. in Political Science, University of the Punjab, Lahore. Session 2013 – 2018 Supervisor Prof. Dr. Umbreen Javaid Chairperson Department of Political Science Submitted by Sarfraz Batool Ph.D. (Political Science) Roll No. 04 Session: 2013-2018 ii DEDICATION I dedicate my thesis to my loving mother and caring husband, without their support and encouragement I could not have completed this thesis. I also dedicate this work to the golden memories of my late father. May his soul rest in peace forever. Ameen iii DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the result of my individual research and I have not submitted this thesis concurrently to any other University or Institute for any other degree whatsoever Sarfraz Batool iv Certificate of Approval It is certified that this Ph.D. Thesis submitted by Sarfraz Batool on the topic of ―Regional Integration and Liberal Economic order in SAARC: A Case Study of Trade Relations between Pakistan and India under SAFTA Regime (1997-2015)” is an original work and result of her own efforts. In assessment of the ‗Examining Committee‘, this thesis is of sufficient standard to warrant the acceptance by the Department of Political Science, University of the Punjab, Lahore for the award of Ph.D. -

RIS BIBLIOGRAPHY on SOUTH-SOUTH COOPERATION

NeST fodkl'khy ns'kksa dh vuqla/ku ,oa lwpuk iz.kkyh Network of Southern Think-Tanks Hkkjrh; fodkl lg;ksx eap fons'k ea=kky; la;qDr jk"Vª Hkkjr ljdkj RIS BIBLIOGRAPHY on SOUTH-SOUTH COOPERATION fodkl'khy ns'kksa dh vuqla/ku ,oa lwpuk iz.kkyh South - South Cooperation Select Bibliography* 2016 * On-going work: by no means exhaustive. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the RIS Bibliography on South-South Cooperation, we have compiled selected books/ documents and research articles on five selected broad sectors viz. Broad Themes, Trade and Investment, Sectoral Studies, Technology and Technology Transfer and Miscellaneous. It is a result of collective efforts made by a research team led by Dr. Beena Pandey. A special mention must be made of the core support provided by Ms. Kashika Arora, Ms. Akanksha Batra, Mr. Pratyush, Mr. Divya Prakash, and Mrs. Jyoti and Mrs. Sushila from the RIS Library. Contents I Broad Themes II Trade and Investment III Sectoral Studies IV Technology and Technology Transfer V Miscellaneous I Broad Themes Abbasi, M. 2012. “Sustainable Practices in Pakistani Manufacturing Supply Chains: Motives, Sharing Mechanism and Performance Outcome”. Journal of Quality and Technology Management. 8 (2). 51–74. Abdenur, Adriana Erthal, and João Moura Estevão Marques Da Fonseca. 2013. "The North’s growing role in South–South cooperation: Keeping the Foothold”. Third World Quarterly. 34 (8). Abduraxmonovich, Abdurahim Okunov. 2003. “Economic Cooperation between India and Central Asian Republics with Special Reference to Uzbekistan”. RIS Discussion Paper, No.53. RIS, New Delhi. 23p. Abe, M. 2013. Expansion of Global Value Chains in Asian Developing Countries: Automotive Case Study in the Mekong Subregion. -

List of Acronyms

List of Acronyms ACU Asian Clearing Union CDIS Co-ordinated Direct Investment Survey ADB Asian Development Bank CDS Credit Demand Survey AOD Academy of Design CE Compensation of Employees APPFs Approved Pension and Provident Funds CEA Central Environmental Authority APREA Asia Pacific Real Estate Association CEB Ceylon Electricity Board APTA Asia-Pacific Trade Agreement CEFTS Common Electronic Fund Transfer Switch ARF Agency Results Framework CEMD Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths ASI Annual Survey of Industries CEO Chief Executive Officer ASPI All Share Price Index CEP Central Expressway Project ATMs Automated Teller Machines CEPAs Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements ATI Advanced Technological Institutions CFC Consumption of Fixed Capital ATM Average Time to Maturity CFC Ceylon Fisheries Corporation ATMs Advanced Traffic Management System CGSPA Credit Guarantee Scheme for Pawning Advances ATPF Asian Trade Promotion Forum CHOGM Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting ATS Automated Trading System CICT Colombo International Container Terminal AWCMR Average Weighted Call Money Rate CIF Cost, Insurance and Freight AWDR Average Weighted Deposit Rate CINEC Colombo International Nautical and Engineering AWFDR Average Weighted Fixed Deposit Rate College AWLR Average Weighted Lending Rate CIS Commonwealth of Independent States AWNDR Average Weighted New Deposit Rate CIT Cheque Imaging and Truncation AWNLR Average Weighted New Lending Rate CKAH Colombo-Kandy Alternate Highway AWPR Average Weighted Prime Lending Rate CKDu Chronic -

South Asia Economic Union

Towards South Asia Economic Union Proceedings of the 7th South Asia Economic Summit (SAES) 5-7 November 2014 New Delhi, India Copyright © RIS ISBN: 81-7122-144-9 Published in 2015 by: Core IV-B, Fourth Floor, India Habitat Centre Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110 003, India Ph.: +91-11-24682177-80, Fax: +91-11-24682173-74 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ris.org.in Table of Contents Foreword by Ambassador Shyam Saran, Chairman, RIS ...........................................v Preface by Prof. Sachin Chaturvedi, Director General, RIS .....................................vii Acknowledgements .....................................................................................................ix List of Abbreviations ...................................................................................................xi Part I Summary and Recommendations ..........................................................................1 Part II Agenda......................................................................................................................17 Welcome Address by Prof. Sachin Chaturvedi, Director General, RIS ..........27 Opening Address by Amb. Shyam Saran, Chairman, RIS ...............................31 Inaugural Address by Hon’ble M. Hamid Ansari, ..........................................35 Vice-President of India Vote of Thanks by Prof. Prabir De, RIS ................................................................39 Part III South Asia Economic Union: Challenges and Tasks Ahead.............................43 Selim Raihan -

Regional and Global Liquidity Arrangements

Regional and Global Liquidity Arrangements Ulrich Volz / Aldo Caliari (Editors) Regional and global liquidity arrangements Ulrich Volz / Aldo Caliari (eds.) Bonn 2010 German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE) The German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE) is a multidisciplinary research, consultancy and training institute for Germany’s bilateral and for multilateral development co-ope- ration. On the basis of independent research, it acts as consultant to public institutions in Germany and abroad on current issues of co-operation between developed and developing countries. Through its 9-months training course, the German Development Institute prepares German and European University graduates for a career in the field of development policy. Ulrich Volz is Senior Economist at the German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungs- politik (DIE) in Bonn. He also teaches courses in international monetary relations and international finance at Freie Universität Berlin. Aldo Caliari is Director of the Rethinking Bretton Woods Project at the Centre of Concern, Washington, DC. © Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik gGmbH Tulpenfeld 6, 53113 Bonn, Germany +49 (0)228 94927-0 +49 (0)228 94927-130 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.die-gdi.de Contents Abbreviations Introduction 1 Aldo Caliari / Ulrich Volz The world’s liquidity arrangements: The easiest item on a holistic agenda for international monetary reform? 8 Graham Bird The IMF as an international lender of last resort 13 Edwin M. Truman Regional and global liquidity arrangements for a more democratic and human world: The potential of SDRs 17 Pedro Páez Pérez A suggestion for the IMF: Embrace regionalism 20 Raj M. -

Enhancing South-South Trade and Investment Finance

11 October 2005 English Only ENHANCING SOUTH-SOUTH TRADE AND INVESTMENT FINANCE Background note by the UNCTAD secretariat Executive summary South-South trade grows much faster than world trade, and so do South-South investments. The latter now account for more than one third of investment flows into developing countries. This is despite the fact that financing support for such South-South flows are weak: the generic gaps that exist in the financing system for commodity trade and investments in developing countries are even more pronounced for such non-traditional transactions. The availability of finance, in particular for the medium- to long-term, is often poor for developing country exporters, importers and investors. International banks apply strict country credit ceilings, and impose high risk premiums on lending to developing countries. Financing for South-South investments and trade is particularly scarce. While the institutional capacity of developing country banks to provide finance to non-traditional sectors is improving, several factors are hurting the availability of funds – in particular, the consolidation of the international banking sector (which reduces overall country credit lines), and the forthcoming Basel 2 New Capital Accord (which also will reduce country credit lines for the more “risky” countries, and will lead to higher risk premiums for non-investment grade clients). While gaps in trade and investment finance remain (and continue leading to a non-level playing field for non-OECD companies), these institutional developments have to be taken into account when considering the shape and form of a prospective new arrangement to deal with the financing gap for South-South trade and investments. -

India As the Engine of Recovery for South Asia | 5

REPORT INDIA AS THE ENGINE OF RECOVERY FOR SOUTH ASIA A Multi-Sectoral Plan for India’s Covid-19 Diplomacy in the Region August 2020 Shyam Saran Gautam Mukhopadhaya Nimmi Kurian Sandeep Bhardwaj www.cprindia.org The Covid-19 pandemic presents an unparalleled challenge to the peace and prosperity of South Asia, home to one-fourth of the world population. Aside from the immediate health crisis, the pandemic also threatens to undo decades of economic development in the region and destabilize it socially and politically. It is imperative that India take on the “ leadership role in the region during this time of crisis. As the largest nation in South Asia, it needs to assume the responsibility of assisting its neighbourhood in combating the pandemic and getting on the path of a sustained recovery. This report, from the International Relations team at the Centre for Policy Research, offers a multi-sectoral action plan for India’s Covid-19 diplomacy in the region, covering critical areas of health, food security, ecology, trade and finance. Focusing on the immediate problems as well as long-term challenges, the report envisions a prosperous South Asia, with India as its engine of recovery. ” Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Yamini Aiyar for her leadership and support. Special thanks to Sanjay Kathuria and Namrata Raju for their helpful advice. This report is a product of collaboration from the International Relations team at the Centre for Policy Research. www.cprindia.org TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 4 2. Key Challenges Facing South Asia Due to COVID-19 6 FIG.