Debt Vulnerabilities in Developing Countries: a New Debt Trap?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

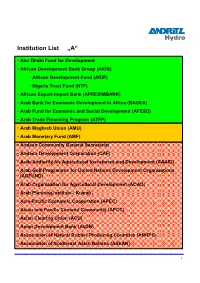

Institution List „A“

Institution List „A“ • Abu Dhabi Fund for Development • African Development Bank Group (AfDB) • African Development Fund (AfDF) • Nigeria Trust Fund (NTF) • African Export-Import Bank (AFREXIMBANK) • Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa (BADEA) • Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development (AFESD) • Arab Trade Financing Program (ATFP) • Arab Maghreb Union (AMU) • Arab Monetary Fund (AMF) • Andean Community General Secretariat • Andean Development Corporation (CAF) • Arab Authority for Agricultural Investment and Development (AAAID) • Arab Gulf Programme for United Nations Development Organizations (AGFUND) • Arab Organization for Agricultural Development (AOAD) • Arab Planning Institute - Kuwait • Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) • Asian and Pacific Coconut Community (APCC) • Asian Clearing Union (ACU) • Asian Development Bank (AsDB) • Association of Natural Rubber Producing Countries (ANRPC) • Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) 1 Institution List „B-C“ • Bank of Central African States (BEAC) • Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO) • Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) • Baltic Council of Ministers • Bank for International Settlements (BIS) • Black Sea Trade and Development Bank (BSTDB) • Caribbean Centre for Monetary Studies (CCMS) • Caribbean Community (CARICOM) • Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) • Caribbean Regional Technical Assistance Centre (CARTAC) • Center for Latin American Monetary Studies (CEMLA) • Center for Marketing Information and Advisory Services for Fishery Products -

Development of Payment and Settlement System

CHAPTER 7 Development of Payment and Settlement System Khin Thida Maw This chapter should be cited as: Khin Thida Maw, 2012. “Development of Payment and Settlement System.” In Economic Reforms in Myanmar: Pathways and Prospects, edited by Hank Lim and Yasuhiro Yamada, BRC Research Report No.10, Bangkok Research Center, IDE- JETRO, Bangkok, Thailand. Chapter 7 Development of Payment and Settlement System Khin Thida Maw ______________________________________________________________________ Abstract The new government of Myanmar has proved its intention to have good relations with the international community. Being a member of ASEAN, Myanmar has to prepare the requisite measures to assist in the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community in 2015. However, the legacy of the socialist era and the tight control on the banking system spurred people on to cash rather than the banking system for daily payment. The level of Myanmar’s banking sector development is further behind the standards of other regional banks. This paper utilizes a descriptive approach as it aims to provide the reader with an understanding of the current payment and settlement system of Myanmar’s financial sector and to recommend some policy issues for consideration. Section 1 introduces general background to the subject matter. Section 2 explains the existing domestic and international payment and settlement systems in use by Myanmar. Section 3 provides description of how the information has been collected and analyzed. Section 4 describes recent banking sector developments and points for further consideration relating to payment and settlement system. And Section 5 concludes with the suggestions and recommendation. ______________________________________________________________________ 1. Introduction Practically speaking, Myanmar’s economy was cash-based due to the prolonged decline of the banking system after nationalization beginning in the early 1960s. -

The Coronavirus Crisis and Debt Relief Loan Forbearance and Other Debt Relief Have Been Part of the Effort to Help Struggling Households and Businesses

The Coronavirus Crisis and Debt Relief Loan forbearance and other debt relief have been part of the effort to help struggling households and businesses By John Mullin he pandemic’s harmful financial effects have been distributed unevenly — so much so that the headline macroeconomic numbers generally have not captured the experiences of those T who have been hardest hit financially. Between February and April, for example, the U.S. personal savings rate actually increased by 25 percentage points. This macro statistic reflected the reality that the majority of U.S. workers remained employed, received tax rebates, and reduced their consumption. But the savings data did not reflect the experiences of many newly unemployed service sector workers. And there are additional puzzles in the data. The U.S. economy is now in the midst of the worst economic downturn since World War II, yet the headline stock market indexes — such as the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500 — are near record highs, and housing prices have gener- ally remained firm. How can this be? Many observers agree that the Fed’s expansionary monetary policy is playing a substantial role in supporting asset prices, but another part of the explanation may be that the pandemic’s economic damage has been concentrated among firms that are too small to be included in the headline stock indexes and among low-wage workers, who are not a major factor in the U.S. housing market. 4 E con F ocus | s Econd/T hird Q uarTEr | 2020 Share this article: https://bit.ly/debt-covid Policymakers have taken aggressive steps to miti- borrowers due to the pandemic.” They sought to assure gate the pandemic’s financial fallout. -

Debtbook Diplomacy China’S Strategic Leveraging of Its Newfound Economic Influence and the Consequences for U.S

POLICY ANALYSIS EXERCISE Debtbook Diplomacy China’s Strategic Leveraging of its Newfound Economic Influence and the Consequences for U.S. Foreign Policy Sam Parker Master in Public Policy Candidate, Harvard Kennedy School Gabrielle Chefitz Master in Public Policy Candidate, Harvard Kennedy School PAPER MAY 2018 Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. This paper was completed as a Harvard Kennedy School Policy Analysis Exercise, a yearlong project for second-year Master in Public Policy candidates to work with real-world clients in crafting and presenting timely policy recommendations. Design & layout by Andrew Facini Cover photo: Container ships at Yangshan port, Shanghai, March 29, 2018. (AP) Copyright 2018, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America POLICY ANALYSIS EXERCISE Debtbook Diplomacy China’s Strategic Leveraging of its Newfound Economic Influence and the Consequences for U.S. Foreign Policy Sam Parker Master in Public Policy Candidate, Harvard Kennedy School Gabrielle Chefitz Master in Public Policy Candidate, Harvard Kennedy School PAPER MARCH 2018 About the Authors Sam Parker is a Master in Public Policy candidate at Harvard Kennedy School. Sam previously served as the Special Assistant to the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs at the Department of Homeland Security. As an academic fellow at U.S. Pacific Command, he wrote a report on anticipating and countering Chinese efforts to displace U.S. -

Using Bankruptcy to Provide Relief from Tax Debt Explore All Options

USING BANKRUPTCY TO PROVIDE RELIEF FROM TAX DEBT EXPLORE ALL OPTIONS - Collection Statute End Date--IRC § 6502 - Offer in Compromise--IRC § 7122 - Installment Agreement--IRC § 6159 - Currently uncollectible status THE BANKRUPTCY OPTION - Chapter 7--liquidation - Chapter 13--repayment plan - Chapter 12--family farmers and fishers - Chapter 11--repayment plan, larger cases The names come from the chapters where the rules are found in Title 11 of the United States Code. This presentation focuses on federal income taxes in Chapter 7. In Chapter 13, the debt relief rules for taxes are similar to the Chapter 7 rules. VOCABULARY - Secured debt--payment protected by rights in property, e.g., mortgage or statutory lien - Unsecured debt--payment protected only by debtor’s promise to pay - Priority--ranking of creditor’s claim for purposes of asset distribution - Discharge--debtor’s goal in bankruptcy, eliminate the debt SECURED DEBT - Bankruptcy does not eliminate, i.e., discharge, secured debt - IRS creates secured debt with a properly filed notice of federal tax lien (NFTL) - Valid NFTL must identify taxpayer, tax year, assessment, and release date--Treas. Reg. § 301.6323-1(d)(2) - Rules for proper place to file NFTL vary by state SECURED DEBT CONTINUED - Properly filed NFTL attaches to all property - All means all; NFTL defeats exemptions (exemptions are debtor’s rights to protect some property from creditors) - Never assume NFTL is valid - If NFTL is valid, effectiveness of bankruptcy is problematic; it will depend on the debtor’s assets SECURED -

Introduction Establishment

ACU 1974 INTRODUCTION OBJECTIVES Secretary General settlement periods by a decision taken by unanimous vote of all of the Directors. Asian Clearing Union (ACU) is the simplest form of • To provide a facility to settle payments, on a multilateral The Board is authorized to appoint a Secretary General payment arrangements whereby the participants settle basis, for current international transactions among for a term of three years. The Secretary General may Interest payments for intra-regional transactions among the the territories of participants; be reappointed and shall cease to hold office when the Interest shall be paid by net debtors and transferred to participating central banks on a multilateral basis. The Board so decides. • To promote the use of participants’ currencies net creditors on daily outstandings between settlement main objectives of a clearing union are to facilitate in current transactions between their respective Agent dates. The rate of interest applicable for a settlement payments among member countries for eligible territories and thereby effect economies in the use period will be the closing rate on the first working day transactions, thereby economizing on the use of foreign The Board of Directors may make arrangements with of the participants’ exchange reserves; of the last week of the previous calendar month offered exchange reserves and transfer costs, as well as a central bank or monetary authority of a participant by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) for one promoting trade among the participating countries. The • To promote monetary cooperation among the to provide the necessary services and facilities for the month US dollar and Euro deposits. -

Boc-Boe Sovereign Default Database: What's New in 2021

BoC–BoE Sovereign Default Database: What’s new in 2021? by David Beers1, 1 Elliot Jones2, Zacharie Quiviger and John Fraser Walsh3 The views expressed this report are solely those of the authors. No responsibility for them should be attributed to the Bank of Canada or the Bank of England. 1 [email protected], Center for Financial Stability, New York, NY 10036, USA 2 [email protected], Financial Markets Department, Reserve Bank of New Zealand, Auckland 1010, New Zealand 3 [email protected], [email protected] Financial and Enterprise Risk Department Bank of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1A 0G9 1 Acknowledgements We are grateful to Mark Joy, James McCormack, Carol Ann Northcott, Alexandre Ruest, Jean- François Tremblay and Tim Willems for their helpful comments and suggestions. We thank Banu Cartmell, Marie Cavanaugh, John Chambers, James Chapman, Stuart Culverhouse, Patrisha de Leon-Manlagnit, Archil Imnaishvili, Marc Joffe, Grahame Johnson, Jamshid Mavalwalla, Philippe Muller, Papa N’Diaye, Jean-Sébastien Nadeau, Carolyn A. Wilkins and Peter Youngman for their contributions to earlier research papers on the database, Christian Suter for sharing previously unpublished data he compiled with Volker Bornschier and Ulrich Pfister in 1986, Carole Hubbard for her excellent editorial assistance, and Michael Dalziel and Natalie Brule, and Sandra Newton, Sally Srinivasan and Rebecca Mari, respectively, for their help designing the Bank of Canada and Bank of England web pages and Miranda Wang for her efforts updating the database. Any remaining errors are the sole responsibility of the authors. 2 Introduction Since 2014, the Bank of Canada (BoC) has maintained a comprehensive database of sovereign defaults to systematically measure and aggregate the nominal value of the different types of sovereign government debt in default. -

Debt Relief Services & the Telemarketing Sales Rule

DEBT RELIEF SERVICES & THE TELEMARKETING SALES RULE: A Guide for Business Federal Trade Commission | ftc.gov Many Americans struggle to pay their credit card bills. Some turn to businesses offering “debt relief services” – for-profit companies that say they can renegotiate what consumers owe or get their interest rates reduced. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the nation’s consumer protection agency, has amended the Telemarketing Sales Rule (TSR) to add specific provisions to curb deceptive and abusive practices associated with debt relief services. One key change is that many more businesses will now be subject to the TSR. Debt relief companies that use telemarketing to contact poten- tial customers or hire someone to call people on their behalf have always been covered by the TSR. The new Rule expands the scope to cover not only outbound calls – calls you place to potential customers – but in-bound calls as well – calls they place to you in response to advertisements and other solicita- tions. If your business is involved in debt relief services, here are three key principles of the new Rule: ● It’s illegal to charge upfront fees. You can’t collect any fees from a customer before you have settled or other- wise resolved the consumer’s debts. If you renegotiate a customer’s debts one after the other, you can collect a fee for each debt you’ve renegotiated, but you can’t front-load payments. You can require customers to set aside money in a dedicated account for your fees and for payments to creditors and debt collectors, but the new Rule places restrictions on those accounts to make sure customers are protected. -

Sovereign Default: Which Shocks Matter?

Sovereign default: which shocks matter? Bernardo Guimaraes∗ April 2010 Abstract This paper analyses a small open economy that wants to borrow from abroad, cannot commit to repay debt but faces costs if it decides to default. The model generates analytical expressions for theimpactofshocksontheincentivecompatiblelevel of debt. Debt reduction generated by severe output shocks is no more than a couple of percentage points. In contrast, shocks to world interest rates can substantially affect the incentive compatible level of debt. Keywords: sovereign debt; default; world interest rates; output shocks. Jel Classification: F34. 1Introduction What generates sovereign default? Which shocks are behind the episodes of debt crises we observe? The answer to the question is crucial to policy design. If we want to write contingent contracts,1 build and operate a sovereign debt restructuring mechanism,2 or an international lender of last resort,3 we need to know which economic variables are subject to shocks that significantly increase incentives for default or could take a country to “bankruptcy”. I investigate this question by studying a small open economy that wants to borrow from abroad, cannot commit to repay debt but faces costs if it decides to default. There is an incentive compatible level of sovereign debt – beyond which greater debt triggers default –anditfluctuates with economic conditions. The renegotiation process is costless and restores debt to its incentive compatible level. The model yields analytical expressions ∗London School of Economics, Department of Economics, and Escola de Economia de Sao Paulo, FGV-SP; [email protected]. I thank Giancarlo Corsetti, Nicola Gennaioli, Alberto Martin, Silvana Tenreyro, Alwyn Young and, especially, Francesco Caselli for helpful comments, several seminar participants for their inputs and ZsofiaBaranyand Nathan Foley-Fisher for excellent research assistance financed by STICERD. -

Conditionality, Debt Relief, and the Developing Country Debt Crisis

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Developing Country Debt and Economic Performance, Volume 1: The International Financial System Volume Author/Editor: Jeffrey D. Sachs, editor Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-73332-7 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/sach89-1 Conference Date: September 21-23, 1987 Publication Date: 1989 Chapter Title: Conditionality, Debt Relief, and the Developing Country Debt Crisis Chapter Author: Jeffrey D. Sachs Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8992 Chapter pages in book: (p. 255 - 296) 6 Conditionality, Debt Relief, and the Developing Country Debt Crisis Jeffrey D. Sachs 6.1 Introduction This chapter examines the role of high-conditionality lending by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank as a part of the overall management of the debt crisis. High-conditionality lending re- fers to the process in which the international institutions make loans based on the promise of the borrowing countries to pursue a specified set of policies. High-conditionality lending by both institutions has played a key role in the management of the crisis since 1982, though the results of such lending have rarely lived up to the advertised hopes. One major theme of this chapter is that the role for high-conditionality lending is more restricted than generally believed, since the efficacy of conditionality is inherently limited. A related theme is that many programs involving high-conditionality lending could be made more effective by including commercial bank debt relief as a component of such programs. -

Student Loan Repayment Guide

Can’t afford your student Maura Healey loans? Worried about your Attorney General credit score? If you’re struggling with student loan debt, it’s important to explore your federal student loan repayment options. Maura Healey You may find that you have surprisingly affordable options to Attorney General lower your monthly payment, avoid default, and preserve your credit score. Your repayment options depend Student Loan upon your loan type and repayment status. Repayment There are also very limited If you’re struggling with student circumstances in which your loan debt, you may have Guide debt can be cancelled. options. Managing student loan debt isn’t File a Student Loan easy. But you should never pay File a Student Loan Help companies for student loan help. Help Request with the Request on our website: Attorney General’s To get free help with your student www.mass.gov/ago/studentloans loans, file a Student Loan Help or call our Student Loan Helpline Student Loan Request on our website: for free help and information: Ombudsman WWW.MASS.GOV/AGO/STUDENTLOANS 1-888-830-6277 WWW.MASS.GOV/AGO/STUDENTLOANS or call our Student Loan Helpline at 1-888-830-6277. Call the Student Loan Helpline Student Loan Helpline: 1-888-830-6277 1-888-830-6277 WWW.MASS.GOV/AGO/STUDENTLOANS If you enroll in an IDR plan, you need to recertify income information each year. Failure to annually recertify will undo many of the benefits of enrolling. To learn more about federal loan repayment options, including IDR plans, visit the U.S. -

Debt Trap? Chinese Loans and Africa’S Development Options

AUGUST 2018 POLICY INSIGHTS 66 DEBT TRAP? CHINESE LOANS AND AFRICA’S DEVELOPMENT OPTIONS ANZETSE WERE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Africa’s growing public debt has sparked a renewed global debate about debt sustainability on the continent. This is largely owing to the emergence of China as a major financier of African infrastructure, resulting in a narrative that China is using debt to gain geopolitical leverage by trapping poor countries in unsustainable loans. This policy insight uses data on African debt to interrogate this notion. It explains why African debt is rising and why Chinese loans are particularly attractive from the viewpoint of African governments. It concludes that the debt trap narrative underestimates the decision-making power of African governments. ABOUT THE AUTHOR However, there are important caveats for African governments. These include the impact of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) on African ANZETSE WERE development agendas, the possible impact of spiralling debt on African is a Development sovereignty, and the complex impact of corruption. Economist with an MA in Economics from the INTRODUCTION University of Sydney and a BA from Brown The increase in public debt in Africa has been a subject of scrutiny in recent University. She is a years. This policy insight examines the rise of sovereign debt in Africa, with a weekly columnist for focus on Chinese lending. It seeks to understand why African debt is growing, Business Daily Africa taking into account the geopolitical context of China–Africa relations that (anzetsewere.wordpress. informs the uptake of, response to, and implications of rising public debt in com).