Development of Payment and Settlement System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BANKING and FINANCE in MYANMAR BANKING and FINANCE in MYANMAR Iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This Paper Was Written by Sean Turnell

II BANKING AND FINANCE IN MYANMAR BANKING AND FINANCE IN MYANMAR III ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper was written by Sean Turnell. The author is grateful for comments and suggestions on earlier drafts from Steve Parker, Lynn Salinger, Daniel Swift (USAID), Tocher Mitchell, Bruce Bolnick, Timothy Buehrer, Show Ei Ei Tun, BANKING and other participants in the Economic Reform and Growth Dynamics Study workshop held at the PSDA office in Yangon, Myanmar, on January 13–14, 2016. The author also benefited from useful discussions with Declan McGee AND FINANCE (the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development), from the members of the National League for Democracy’s Economic Committee, and from a wide variety of people in Myanmar’s banking fraternity. IN MYANMAR PRESENT REALITIES, FUTURE POSSIBILITIES PHOTO CREDITS DISCLAIMER The team would like to thank the following for the photos provided. This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for - Jeffrey Barth International Development (USAID). Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not - Soe Zeya Tun necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government. - Tom Cheatham - Asian Development Bank II- World Bank BANKING AND FINANCE IN MYANMAR BANKING AND FINANCE IN MYANMAR III ECONOMIC REFORM AND GROWTH DYNAMICS DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES LIST OF ACRONYMS In 2015, as Myanmar prepared for new elections, the United States Agency AGD Asia Green Development Bank for International Development (USAID) commissioned a set of discussion AML Anti-money laundering papers to review Myanmar’s economic status, benchmark its performance ANZ Australia and New Zealand Banking Group relative to other countries, and identify priority policy reforms, investments, APG Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering and institutional innovations to re-establish the country on a new, ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations inclusive growth path. -

Institution List „A“

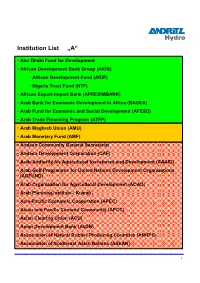

Institution List „A“ • Abu Dhabi Fund for Development • African Development Bank Group (AfDB) • African Development Fund (AfDF) • Nigeria Trust Fund (NTF) • African Export-Import Bank (AFREXIMBANK) • Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa (BADEA) • Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development (AFESD) • Arab Trade Financing Program (ATFP) • Arab Maghreb Union (AMU) • Arab Monetary Fund (AMF) • Andean Community General Secretariat • Andean Development Corporation (CAF) • Arab Authority for Agricultural Investment and Development (AAAID) • Arab Gulf Programme for United Nations Development Organizations (AGFUND) • Arab Organization for Agricultural Development (AOAD) • Arab Planning Institute - Kuwait • Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) • Asian and Pacific Coconut Community (APCC) • Asian Clearing Union (ACU) • Asian Development Bank (AsDB) • Association of Natural Rubber Producing Countries (ANRPC) • Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) 1 Institution List „B-C“ • Bank of Central African States (BEAC) • Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO) • Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) • Baltic Council of Ministers • Bank for International Settlements (BIS) • Black Sea Trade and Development Bank (BSTDB) • Caribbean Centre for Monetary Studies (CCMS) • Caribbean Community (CARICOM) • Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) • Caribbean Regional Technical Assistance Centre (CARTAC) • Center for Latin American Monetary Studies (CEMLA) • Center for Marketing Information and Advisory Services for Fishery Products -

Financial Institutions of Myanmar Law (1990) 1

Financial Institutions of Myanmar Law (1990) 1 The State Law and Order Restoration Council The Financial Institutions of Myanmar Law (The State Law and Order Restoration Council Law No. 16/90) The 13th Waxing Day of Waso, 1352 M.E. (4th July, 1990) The State Law and Order Restoration Council hereby enacts the following Law:- Chapter I Title and Definition This Law shall be called the Financial Institutions of Myanmar Law. 2. The following expressions contained in this Law shall have the meanings given hereunder:- (a) Financial Institution means an enterprise established in the State, whose corporate purpose is intermediation on the money or capital markets through the collection of financial resources from third parties for investment on their own account in credit operations, credit and public debt instruments, securities, or other authorized financial activities; (b) Central Bank means the Central Bank of Myanmar; (c) Board means the Board of Directors of the Financial Institution; (d) Chairman means the Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Financial Institution; (e) Member means the member of the Board of Directors of the Financial Institution. 1 http://www.investinmyanmar.com/myanmar-investment-laws/ 26 September 2014. 2 Chapter II Establishment 3. (a) The Financial Institutions other than those specifically established under this Law shall be established as limited liability company in accordance with the Myanmar Companies Act as well as with the Special Company Act, 1950; (h) This Law shall apply to the financial institutions. 4. The shares and stock any financial institution, with or without voting rights, shell be registered. Preferencial shares shall not be converted into share or stock with voting rights. -

The Role of Central Banks in Scaling up Sustainable Finance: What Do Monetary Authorities in Asia and the Pacific Think? ADBI Working Paper 1099

ADBI Working Paper Series THE ROLE OF CENTRAL BANKS IN SCALING UP SUSTAINABLE FINANCE: WHAT DO MONETARY AUTHORITIES IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC THINK? Aziz Durrani, Ulrich Volz, and Masyitah Rosmin No. 1099 March 2020 Asian Development Bank Institute Aziz Durrani is a senior financial sector specialist at the South East Asian Central Banks (SEACEN) Research and Training Centre. Ulrich Volz is director of the SOAS Centre for Sustainable Finance and reader in economics at SOAS University of London; and senior research fellow at the German Development Institute. Masyitah Rosmin is a research associate at the SEACEN Centre. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. The Asian Development Bank refers to “China” as the People’s Republic of China. In this report, “$” refers to United States dollars, unless otherwise stated. Suggested citation: Durrani, A., U. -

Myanmar's Economy in 2006

0 MYANMAR – THE STATE, COMMUNITY AND THE ENVIRONMENT ASSESSING THE ECONOMIC SITUATION AFTER THE 2001–2002 BANKING CRISIS Myanmar’s economy in 00 Sean Turnell Myanmar was likely to experience moderate but superficial economic growth through 2006. The country’s ruling military regime, the self- styled State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), has claimed GDP growth rates in excess of 10 per cent per annum for almost a decade. If true, this would make Myanmar one of the world’s fastest and most consistently growing economies. These claims are without foundation, but a growth rate of between 1.5 and 4 per cent was not beyond reach for 2006. Such growth, however, would primarily be a consequence of the high prices Myanmar can now command for its exports of natural gas, and from greater export volumes of gas from new fields currently being brought on stream. In every other respect, Myanmar’s economy will continue to under-perform, in terms of its own potential and relative to that of its neighbours and peers. Indeed, to a large degree, Myanmar’s probable rising gas exports will bring about unfortunate consequences for the country—allowing the SPDC to postpone the economic and political reforms the country needs if its people are to enjoy any measure of economic security. Myanmar, in short, will likely experience a ‘gas curse’ MYANMAR’S ECONOMY IN 2006 0 every bit as inimical to good economic policymaking as has often been a by-product of oil elsewhere. Myanmar is one of the poorest countries in Southeast Asia, yet, only 50 years ago, it was one of the wealthiest. -

Introduction Establishment

ACU 1974 INTRODUCTION OBJECTIVES Secretary General settlement periods by a decision taken by unanimous vote of all of the Directors. Asian Clearing Union (ACU) is the simplest form of • To provide a facility to settle payments, on a multilateral The Board is authorized to appoint a Secretary General payment arrangements whereby the participants settle basis, for current international transactions among for a term of three years. The Secretary General may Interest payments for intra-regional transactions among the the territories of participants; be reappointed and shall cease to hold office when the Interest shall be paid by net debtors and transferred to participating central banks on a multilateral basis. The Board so decides. • To promote the use of participants’ currencies net creditors on daily outstandings between settlement main objectives of a clearing union are to facilitate in current transactions between their respective Agent dates. The rate of interest applicable for a settlement payments among member countries for eligible territories and thereby effect economies in the use period will be the closing rate on the first working day transactions, thereby economizing on the use of foreign The Board of Directors may make arrangements with of the participants’ exchange reserves; of the last week of the previous calendar month offered exchange reserves and transfer costs, as well as a central bank or monetary authority of a participant by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) for one promoting trade among the participating countries. The • To promote monetary cooperation among the to provide the necessary services and facilities for the month US dollar and Euro deposits. -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved. -

Five-Point Road Map of the State Administration Council

BEWARE OF FLOODING AND STRONG WINDS IN MONSOON PAGE-8 (OPINION) Vol. VIII, No. 111, 1st Waxing of Wagaung 1383 ME www.gnlm.com.mm Sunday, 8 August 2021 Five-Point Road Map of the State Administration Council 1. The Union Election Commission will be reconstituted and its mandated tasks, including the scrutiny of voter lists, shall be implemented in accordance with the law. 2. Effective measures will be taken with added momentum to prevent and manage the COVID-19 pandemic. 3. Actions will be taken to ensure the speedy recovery of businesses from the impact of COVID-19. 4. Emphasis will be placed on achieving enduring peace for the entire nation in line with the agreements set out in the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement. 5. Upon accomplishing the provisions of the state of emergency, free and fair multiparty democratic elections will be held in line with the 2008 Constitution, and further work will be undertaken to hand over State duties to the winning party in accordance with democratic standards. Message from Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, Chairman of State Administration Council on the occasion of 54th Anniversary of ASEAN to the people TODAY marks the 54th Anniversary of the founding of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). ASEAN was established with a common desire and collective will to live together in a region of lasting peace, security and stability, sustained economic growth, and shared prosperity and social progress. On this auspicious day, I have the pleasure to extend my warmest greetings and best wishes to our fellow citizens and to the peoples of ASEAN across the region. -

MHM Yangon Newsletter Vol.18

March 2021 Newsletter In light of the ongoing situation in Myanmar, we have prepared this summary of recent developments in Myanmar Key Contacts in order to ensure our clients are informed of the current situation. 1. ANNOUNCEMENT OF US AND UK SANCTIONS President Biden issued a new Executive Order 14014 titled Blocking Property With Respect To The Situation In Burma on 11 February 2021 requiring assets held in the US or by US persons or certain foreign persons determined by the Secretary to the Treasury and Secretary of State of the US to not be transferred, paid, exported, withdrawn or otherwise dealt in for certain prescribed purposes, including for the benefit of the Myanmar military. Julian Barendse TEL+95-1-9253650 In addition, twelve current and former military leaders (including six members of the State Administration [email protected] Council (“SAC”)) were added to the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control’s list of Specifically Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons pursuant to Executive Order 14014. Of these twelve individuals, two (the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Services (“CIC”) and Deputy Commander-in-Chief, who are the Chairman and Vice Chairman of the SAC respectively) were already sanctioned individuals. Three companies (Cancri Gems & Jewellery Co., Ltd., Myanmar Imperial Jade Co., Ltd. and Myanmar Ruby Enterprise) were also sanctioned. The US Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security has also restricted exports of sensitive items which require a licence for export or re-export, to Myanmar’s Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Home Nirmalan Amirthanesan TEL+95-1-9253657 Affairs, the Myanmar military and other security forces, and announced it is considering further measures. -

Afford Two, Eat One. Financial Inclusion in Rural Myanmar

Afford TWO, Eat ONE Financial Inclusion in Rural Myanmar 1 2 CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................................4 Myanmar: Past & Present ...........................................................................................................................................6 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................................12 Archetypes .....................................................................................................................................................................30 Diversity of the Financial Landscape .......................................................................................................................60 Insights & Findings ..............................................................................................................76 Case Study: Monastery Lending Group ..............................................................................................................90 Case Study: Novitiate Ordination Ceremony .....................................................................................................146 Case Study: The Betel Business .............................................................................................................................168 Looking Ahead ..............................................................................................................................................................180 -

The Central Bank of Myanmar Law Pyidaungsu Hlattaw Law No.16/2013 the 4Th Waxing Day of Waso, 1375 ME 11 July 2013 Pyidaungsu Hluttaw Hereby Enacts This Law

CONVENIENCE TRANSLATION – for further information, contact [email protected] The Central Bank of Myanmar Law Pyidaungsu Hlattaw Law No.16/2013 The 4th waxing day of Waso, 1375 ME 11 July 2013 Pyidaungsu Hluttaw hereby enacts this Law Chapter 1 Title and Definition 1. This law shall be called the Central Bank of Myanmar Law. 2. The following expressions contained in this law shall have the meaning given hereunder; (a) State means the Republic of the Union of Myanmar (b) Government means the Union Government, the Republic of the Union of Myanmar. (c) Ministry means Ministry of finance of the Union Government. (d) Central Bank means the Central Bank of Myanmar established under this Law. (e) Bank means the Bank established under the Myanmar Financial Institution Law. (f) The Financial Institution means the institution permitted to establish under the Myanmar Financial Institution Law. (g) The Note means the notes legally issued by the Central Bank under this Law or previously issued by it. (h) The coin means the coins and the denominations legally issued by the Central Bank under this Law or previously issued by it. (i) In the expansion 'Foreign Currency', the following are inclusive; (1) Foreign Currency notes. (2) The Contract to be paid in Foreign Currency notes or to be paid in abroad. (3) Deposits entrusted in the International Government Financial Institutions, Foreign Central Banks, treasury and Commercial banks. (4) Contracts using in remitting the money from one country to another. (5) Foreign Currency accounts open in the Local banks. (j) Gold means standard gold bars and gold coins using in the international transaction. -

COVID-19 Active Response and Expenditure Support Program: Report and Recommendation of the President

Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors Project Number: 54255-001 August 2020 Proposed Countercyclical Support Facility Loan Republic of the Union of Myanmar: COVID-19 Active Response and Expenditure Support Program Distribution of this document is restricted until it has been approved by the Board of Directors. Following such approval, ADB will disclose the document to the public in accordance with ADB's Access to Information Policy. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 3 August 2020) Currency unit – kyat/s (MK) MK1.00 = $0.00073 $1.00 = MK1,363.69 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank CARES – COVID-19 Active Response and Expenditure Support CBM – Central Bank of Myanmar CERP – COVID-19 Economic Relief Plan COVID-19 – coronavirus disease CPRO – COVID-19 pandemic response option GDP – gross domestic product HSCP – Health Sector Contingency Plan IMF – International Monetary Fund MOHS – Ministry of Health and Sports MOPFI – Ministry of Planning, Finance and Industry MSMEs – micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises OP – operational priority PFM – public financial management PRC – People’s Republic of China TWG – technical working group WHO – World Health Organization NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of Myanmar ends on 30 September. “FY” before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends, e.g., FY2020 ends on 30 September 2020. (ii) In this report, “$” refers to United States dollars. Vice-President Ahmed M. Saeed, Operations 2 Director General Ramesh Subramaniam, Southeast Asia