Recasting Genre in Tennessee Williams's Apprentice Plays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Transcultural Perspective on the Casting of the Rose Tattoo

RSA JOU R N A L 25/2014 GIULIANA MUS C IO A Transcultural Perspective on the Casting of The Rose Tattoo A transcultural perspective on the film The Rose Tattoo (Daniel Mann, 1955), written by Tennessee Williams, is motivated by its setting in an Italian-American community (specifically Sicilian) in Louisiana, and by its cast, which includes relevant Italian participation. A re-examination of its production and textuality illuminates not only Williams’ work but also the cultural interactions between Italy and the U.S. On the background, the popularity and critical appreciation of neorealist cinema.1 The production of the film The Rose Tattoo has a complicated history, which is worth recalling, in order to capture its peculiar transcultural implications in Williams’ own work, moving from some biographical elements. In the late 1940s Tennessee Williams was often traveling in Italy, and visited Sicily, invited by Luchino Visconti (who had directed The Glass Managerie in Rome, in 1946) for the shooting of La terra trema (1948), where he went with his partner Frank Merlo, an occasional actor of Sicilian origins (Williams, Notebooks 472). Thus his Italian experiences involved both his professional life, putting him in touch with the lively world of Italian postwar theater and film, and his affections, with new encounters and new friends. In the early 1950s Williams wrote The Rose Tattoo as a play for Anna Magnani, protagonist of the neorealist masterpiece Rome Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945). However, the Italian actress was not yet comfortable with acting in English and therefore the American stage version (1951) starred Maureen Stapleton instead and Method actor Eli Wallach. -

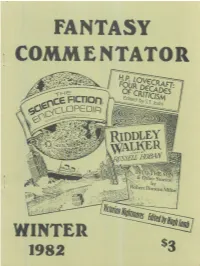

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR and PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR and PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A. Langley Searles Lee Becker, T. G. Cockcroft, 7 East 235th St. Sam Moskowitz, Lincoln Bronx, N. Y. 10470 Van Rose, George T. Wetzel Vol. IV, No. 4 -- oOo--- Winter 1982 Articles Needle in a Haystack Joseph Wrzos 195 Voyagers Through Infinity - II Sam Moskowitz 207 Lucky Me Stephen Fabian 218 Edward Lucas White - III George T. Wetzel 229 'Plus Ultra' - III A. Langley Searles 240 Nicholls: Comments and Errata T. G. Cockcroft and 246 Graham Stone Verse It's the Same Everywhere! Lee Becker 205 (illustrated by Melissa Snowind) Ten Sonnets Stanton A. Coblentz 214 Standing in the Shadows B. Leilah Wendell 228 Alien Lee Becker 239 Driftwood B. Leilah Wendell 252 Regular Features Book Reviews: Dahl's "My Uncle Oswald” Joseph Wrzos 221 Joshi's "H. P. L. : 4 Decades of Criticism" Lincoln Van Rose 223 Wetzel's "Lovecraft Collectors Library" A. Langley Searles 227 Moskowitz's "S F in Old San Francisco" A. Langley Searles 242 Nicholls' "Science Fiction Encyclopedia" Edward Wood 245 Hoban's "Riddley Walker" A. Langley Searles 250 A Few Thorns Lincoln Van Rose 200 Tips on Tales staff 253 Open House Our Readers 255 Indexes to volume IV 266 This is the thirty-second number of Fantasy Commentator^ a non-profit periodical of limited circulation devoted to articles, book reviews and verse in the area of sci ence - fiction and fantasy, published annually. Subscription rate: $3 a copy, three issues for $8. All opinions expressed herein are the contributors' own, and do not necessarily reflect those of the editor or the staff. -

The Satanic Rituals Anton Szandor Lavey

The Rites of Lucifer On the altar of the Devil up is down, pleasure is pain, darkness is light, slavery is freedom, and madness is sanity. The Satanic ritual cham- ber is die ideal setting for the entertainment of unspoken thoughts or a veritable palace of perversity. Now one of the Devil's most devoted disciples gives a detailed account of all the traditional Satanic rituals. Here are the actual texts of such forbidden rites as the Black Mass and Satanic Baptisms for both adults and children. The Satanic Rituals Anton Szandor LaVey The ultimate effect of shielding men from the effects of folly is to fill the world with fools. -Herbert Spencer - CONTENTS - INTRODUCTION 11 CONCERNING THE RITUALS 15 THE ORIGINAL PSYCHODRAMA-Le Messe Noir 31 L'AIR EPAIS-The Ceremony of the Stifling Air 54 THE SEVENTH SATANIC STATEMENT- Das Tierdrama 76 THE LAW OF THE TRAPEZOID-Die elektrischen Vorspiele 106 NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTAIN-Homage to Tchort 131 PILGRIMS OF THE AGE OF FIRE- The Statement of Shaitan 151 THE METAPHYSICS OF LOVECRAFT- The Ceremony of the Nine Angles and The Call to Cthulhu 173 THE SATANIC BAPTISMS-Adult Rite and Children's Ceremony 203 THE UNKNOWN KNOWN 219 The Satanic Rituals INTRODUCTION The rituals contained herein represent a degree of candor not usually found in a magical curriculum. They all have one thing in common-homage to the elements truly representative of the other side. The Devil and his works have long assumed many forms. Until recently, to Catholics, Protestants were devils. To Protes- tants, Catholics were devils. -

Glbtq >> Special Features >> You Are Not the Playwright I Was Expecting: Tennessee Williams's Late Plays

Special Features Index Tennessee Williams's Late Plays Newsletter April 1, 2012 Sign up for glbtq's You Are Not the Playwright I Was Expecting: free newsletter to Tennessee Williams's Late Plays receive a spotlight on GLBT culture by Thomas Keith every month. e-mail address If you are not familiar with the later plays of Tennessee Williams and would like to be, then it is helpful to put aside some assumptions about the playwright, or throw them out entirely. subscribe Except in snatches, snippets, and occasional arias, you will not find privacy policy Williams's familiar language--the dialogue that, as Arthur Miller unsubscribe declared, "plant[ed] the flag of beauty on the shores of commercial theater." Forget it. Let it go and, for better or worse, take the Encyclopedia dialogue as it comes. Discussion go Okay, some of it will still be beautiful. You'll find a few Southern stories, but even those are not your mother's Tennessee Williams. Certain elements of his aesthetic will be recognizable, but these works do not have the rhythms or tone of his most famous plays. No More Southern Belles Williams declared to the press in the early 1960s, "There will be no more Southern belles!" A decade later he told an interviewer, "I used to write symphonies; now I write chamber music, smaller plays." Log In Now You will recognize familiar themes: the plight of Forgot Your Password? outsiders--the fugitive, the sensitive, the Tennessee Williams in Not a Member Yet? isolated, the artist; the nature of compassion 1965. -

The Theatre of Tennessee Williams: Languages, Bodies and Ecologies

Barnett, David. "Index." The Theatre of Tennessee Williams: Languages, Bodies and Ecologies. London: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama, 2014. 295–310. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 29 Sep. 2021. <>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 29 September 2021, 17:43 UTC. Copyright © Brenda Murphy 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. INDEX Major discussions of plays are indicated in bold type . Williams ’ s works are entered under their titles. Plays by other authors are listed under authors ’ names. Actors Studio 87, 95 “ Balcony in Ferrara, Th e ” 55 Adamson, Eve 180 Bankhead, Tallulah 178 Adler, Th omas 163 Barnes, Clive 172, 177, Albee, Edward 167 268n. 17 Alpert, Hollis 189 Barnes, Howard 187 American Blues 95 Barnes, Richard 188 Ames, Daniel R. 196 – 8, Barnes, William 276 203 – 4 Barry, Philip 38 Anderson, Maxwell Here Come the Clowns 168 Truckline Caf é 215 Battle of Angels 2 , 7, 17, 32, Anderson, Robert 35 – 47 , 51, 53, 56, 64, 93, Tea and Sympathy 116 , 119 173, 210, 233, 272 “ Angel in the Alcove, Th e ” Cassandra motif 43 4, 176 censorship of 41 Ashley, Elizabeth 264 fi re scene 39 – 40 Atkinson, Brooks 72, 89, Freudian psychology in 44 104 – 5, 117, 189, 204, political content 46 – 7 209 – 10, 219 – 20 production of 39, 272 Auto-Da-Fe 264 reviews of 40 – 1, 211 Ayers, Lemuel 54, 96 Th eatre Guild production 37 Baby Doll 226 , 273, 276 themes and characters 35 Bak, John S. -

Discovering the Lost Race Story: Writing Science Fiction, Writing Temporality

Discovering the Lost Race Story: Writing Science Fiction, Writing Temporality This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia 2008 Karen Peta Hall Bachelor of Arts (Honours) Discipline of English and Cultural Studies School of Social and Cultural Studies ii Abstract Genres are constituted, implicitly and explicitly, through their construction of the past. Genres continually reconstitute themselves, as authors, producers and, most importantly, readers situate texts in relation to one another; each text implies a reader who will locate the text on a spectrum of previously developed generic characteristics. Though science fiction appears to be a genre concerned with the future, I argue that the persistent presence of lost race stories – where the contemporary world and groups of people thought to exist only in the past intersect – in science fiction demonstrates that the past is crucial in the operation of the genre. By tracing the origins and evolution of the lost race story from late nineteenth-century novels through the early twentieth-century American pulp science fiction magazines to novel-length narratives, and narrative series, at the end of the twentieth century, this thesis shows how the consistent presence, and varied uses, of lost race stories in science fiction complicates previous critical narratives of the history and definitions of science fiction. In examining the implicit and explicit aspects of temporality and genre, this thesis works through close readings of exemplar texts as well as historicist, structural and theoretically informed readings. It focuses particularly on women writers, thus extending previous accounts of women’s participation in science fiction and demonstrating that gender inflects constructions of authority, genre and temporality. -

1385280318233.Pdf

™ CORE ™ SERIOUSly? Free-to-Play? Imagination is powerful. To quote Albert Einstein, “Imagination is more impor- tant than knowledge. For knowledge is limited to all we now know and under- stand, while imagination embraces the entire world, and all there ever will be to know and understand.” Well said. We believe in the power of imagination and how it creates wonder and inspira- tion. Roleplaying games are one of the few things that can do what they do. Some might say they are the last frontier for wild imagination and creativity. We certainly believe so. That’s why we make roleplaying games – to help make that possible. Making roleplaying games the way we have hasn’t helped us spark imagination the way we’d hoped. We want to try something different. First, we’re adopting the Creative Commons license, so that you can contribute to the game in a meaningful way. That way, we can support you in your awesome ideas and help you get them out to your fellow players. Then, we’re going to give away electronic copies of the core book for free. We’ve all bought games that didn’t end up working out for us. That’s why we’re giving this to you for free – so that you can figure out if you like the game before you decide to spend money on it. If you like The Void and you play it, we’re going to put out a bunch of cool ma- terial at very reasonable prices. We’re going to do it buffet-style, so you can pick and choose what works best for you and your group. -

NLA Newsleather November 2020

Issue 5: November 2020 NewsLeather Leather: It’s who you are, not what you wear NLA-Dallas is about Education * Activism * Community A Review of BV Online Attendees at Beyond Vanilla Online on October 3, 2020, were treated to a smorgasbord of kinky information and fun conversation. A couple of classes had wow moments that got us excited and ready for more. Master TC ended his Negotiation class with a demo that left us all reaching for our fans and praying to our gods the scene actually happens when we are nearby, and Doctor Bubbles and KitKat Ann’s look at Fear Play culminated with a surprise mini scene that clearly demonstrated the difference between surprise and suspense. Beginning our journey in exploring the gender spectrum, Maverick introduced us to some of their friends who showed us unequivocally that one’s parts do not always define one’s gender and that assumptions based on appearances can be way off base. Lee Harrington’s thought provoking exploration of Intentional Relationship Design was interwoven with his signature melange of spiritual appreciation and pragmatic application. Throughout the day, classes alternated with pre-recorded videos to keep the educational opportunities going. Butterscotch’s enthusiasm for tea service shined brightly as she walked us through her take on tea. Ursus’ demonstration of a bar shine gave us a glimpse into the world of the bootblacking, offering something for those interested in being a bootblack, as well as those who seek out their service. Fred illuminated the world of cigars and cigar service for attendees, information that was later put to good use at the post-event hybrid virtual and in-person Beyond Vanilla After Dark. -

This Generation a Shifter Will Arise, Hidden Amongst the Lost and Lies

“This generation a Shifter will arise, Hidden amongst the lost and lies. A great many will see The life that could be. The universe will shake; The greatest among us will quake. The towers will fall. The ruled will rule all.” Douglas and Angelia Pershing Prologue Rian growled when a small group of Shifters entered The Council chamber following Navin and Lena. Lena sauntered in, her hips swaying dangerously from side to side. Other than Rian, all eyes in the room were on her. Her long auburn hair was undulating behind her in a tight ponytail. Her green eyes were bright and cold. Her smirk revealed straight white teeth, poised and ready for the kill. “My Lord,” Lena said in her throaty alto. She bowed then, carefully positioning her body in the most flattering way. The new Seer on The Council, a small mousy man with flat brown eyes and little ability to see anything, gulped audibly as he watched Lena. “I am not a feudal lord,” Rian snapped at Lena. “Of course not,” Lena said, rising slowly, allowing the eyes in the room to linger on her lithe body. “You are my god.” Rian’s eyes flicked to her, somehow his copper eyes were both irritated and pleased. He then returned them to the piece of Shifter trash that had entered the room with her. His copper eyes flashed red for a brief moment, appearing more vibrant and cruel than any eyes before. “Navin,” he growled. It was almost as though when Rian ordered the deaths of the Shifter Young nearly 1 thirteen years ago, he had become less than human. -

Judging the Suspect-Protagonist in True Crime Documentaries

Wesleyan University The Honors College Did He Do It?: Judging the Suspect-Protagonist in True Crime Documentaries by Paul Partridge Class of 2018 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors from the College of Film and the Moving Image Middletown, Connecticut April, 2018 Table of Contents Acknowledgments…………………………………...……………………….iv Introduction ...…………………………………………………………………1 Review of the Literature…………………………………………………………..3 Questioning Genre………………………………………………………………...9 The Argument of the Suspect-protagonist...…………………………………......11 1. Rise of a Genre……………………………………………………….17 New Ways of Investigating the Past……………………………………..19 Connections to Literary Antecedents…………………..………………...27 Shocks, Twists, and Observation……………………………..………….30 The Genre Takes Off: A Successful Marriage with the Binge-Watch Structure.........................................................................34 2. A Thin Blue Through-Line: Observing the Suspect-Protagonist Since Morris……………………………….40 Conflicts Crafted in Editing……………………………………………...41 Reveal of Delayed Information…………………………………………..54 Depictions of the Past…………………………………………………….61 3. Seriality in True Crime Documentary: Finding Success and Cultural Relevancy in the Binge- Watching Era…………………………………………………………69 Applying Television Structure…………………………………………...70 (De)construction of Innocence Through Long-Form Storytelling……….81 4. The Keepers: What Does it Keep, What Does ii It Change?..............................................................................................95 -

Camp Chemistry

Camp Chemistry concocts a petri dish of open, positive, progressive lifestyles; a pleasureable potion of lectures, workshops, and events that encourages a paradigm shift in modern relationships and human sexuality serving our mission of Illuminated Eroticism. Our experiments will take place in two uniquely different locations: The Chemistry Lab, located poolside on the second floor, is a sensual playground and party space. Chemistry Lab-yrinth – a lush secluded event space located at Camp Chemistry, near the Ramblewood Labyrinth south of cabins M-R. 4-5pm | Smooching 101 with CJ, in a way that is ultimately stultifying for Chemistry Schedule Sly & the Smoochdome Crew most people. Sexless marriages, affairs, For pairs who want some fresh practice, or and the high divorce rate all reflect the those looking for more kissy techniques, unsustainability of monogamy as it is IN THE CHEMISTRY LAB-YRINTH: this vintage Smoochdome experience is for commonly understood and practiced. you! Please come with a partner. This is a The Tantric model of relating offers an Friday Paramahansa Satyananda Saraswati. The lips-on experience – gawkers will be asked alternative to the monogamous model, to leave. 10-11pm | BDSM on a Budget practices are very similar, but Ananda Nidra although modern practitioners can with Benjamin Jones focuses specifically on pleasure. Lie back come closest to the spirit of authentic Whips, chains, leather, steel, vinyl, rubber. and enjoy! Sunday Tantra in the context of a long-term BDSM is often focused on stuff. Stuff relationship. These perspectives may 11am-12pm | Ananda Nidra (“blissful costs money and a lot of these things are 12-2pm – Avoiding “Poly-Agony” | seem paradoxical at first, but it is possible General Polyamory & Open Relationship sleep”) w/ Mark A. -

The Theatre of Tennessee Williams: Languages, Bodies and Ecologies

Barnett, David. "The 1930s’ Plays (1936–1940)." The Theatre of Tennessee Williams: Languages, Bodies and Ecologies. London: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama, 2014. 9–34. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 28 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472515452.0007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 28 September 2021, 04:57 UTC. Copyright © Brenda Murphy 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. CHAPTER 1 THE 1930s ’ PLAYS (1936 – 1940) Williams in the Thirties Much of Williams ’ s early playwriting was shaped by the social, economic, and artistic environment of the 1930s. His most important theatrical relationship at the time was with director Willard Holland and Th e Mummers of St Louis, a group dedicated to the drama of social action that was vital to American theatrical culture in the 1930s. Candles to the Sun (1937), based on a coal mining strike, and Fugitive Kind (1937), about the denizens of a seedy urban hotel, were both produced by Th e Mummers, and Not About Nightingales (1938), about brutal abuses in the American prison system, was intended for them, although they disbanded before the play was produced. Th e other major infl uence on Williams ’ s early development as a playwright was the playwriting program at the University of Iowa, which he attended in 1937 – 38. Its director, E. C. Mabie, had worked for the Federal Th eatre Project (FTP), the only federally subsidized theatre in American history, which existed briefl y from 1935 until 1939, when its funding was cut by a Congress that objected to its leftist leanings.