Populism and Political Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

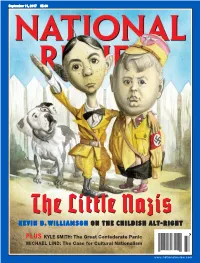

The Little Nazis KE V I N D

20170828 subscribers_cover61404-postal.qxd 8/22/2017 3:17 PM Page 1 September 11, 2017 $5.99 TheThe Little Nazis KE V I N D . W I L L I A M S O N O N T H E C HI L D I S H A L T- R I G H T $5.99 37 PLUS KYLE SMITH: The Great Confederate Panic MICHAEL LIND: The Case for Cultural Nationalism 0 73361 08155 1 www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 1/3/2017 5:38 PM Page 1 !!!!!!!! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! "e Reagan Ranch Center ! 217 State Street National Headquarters ! 11480 Commerce Park Drive, Santa Barbara, California 93101 ! 888-USA-1776 Sixth Floor ! Reston, Virginia 20191 ! 800-USA-1776 TOC-FINAL_QXP-1127940144.qxp 8/23/2017 2:41 PM Page 1 Contents SEPTEMBER 11, 2017 | VOLUME LXIX, NO. 17 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 22 Lucy Caldwell on Jeff Flake The ‘N’ Word p. 15 Everybody is ten feet tall on the BOOKS, ARTS Internet, and that is why the & MANNERS Internet is where the alt-right really lives, one big online 35 THE DEATH OF FREUD E. Fuller Torrey reviews Freud: group-therapy session The Making of an Illusion, masquerading as a political by Frederick Crews. movement. Kevin D. Williamson 37 ILLUMINATIONS Michael Brendan Dougherty reviews Why Buddhism Is True: The COVER: ROMAN GENN Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment, ARTICLES by Robert Wright. DIVIDED THEY STAND (OR FALL) by Ramesh Ponnuru 38 UNJUST PROSECUTION 12 David Bahnsen reviews The Anti-Trump Republicans are not facing their challenges. -

The Honourable Christine Elliott Minister of Health College Park 5Th Floor 777 Bay Street Toronto on M7A 2J3 by Email: [email protected]

The Honourable Christine Elliott Minister of Health College Park 5th Floor 777 Bay Street Toronto ON M7A 2J3 By Email: [email protected] December 4, 2020 Dear Minister Elliott, I am writing today regarding an issue of great concern to some 435 Ontario health care workers represented by the Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada (PIPSC). During the first wave of the pandemic, hospital employees who were unable to work due to a self-isolation requirement arising from a suspected COVID-19 exposure were provided leave with pay in instances where they were asymptomatic and not eligible for sick leave or WSIB. In accordance with direction received from the provincial government through the Ontario Ministry of Health, individual hospitals have begun to implement a very significant change in direction on this critical issue. Asymptomatic employees required to self-isolate due to a suspected exposure while awaiting test results will no longer be paid and are instead being urged to use other forms of leave such as vacation days. This is also being applied to situations where exposure is known to have occurred in the workplace. This new approach is completely unacceptable to our members. While there is no disputing the importance of self-isolation for any and all suspected cases of exposure to COVID-19, particularly in health care, it is abhorrent to penalize essential services workers unable to work due to self-isolation requirements meant to protect their colleagues and their patients. This is especially so when the exposure may have occurred in the workplace itself. -

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

Core 1..39 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 40th PARLIAMENT, 3rd SESSION 40e LÉGISLATURE, 3e SESSION Journals Journaux No. 2 No 2 Thursday, March 4, 2010 Le jeudi 4 mars 2010 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE DAILY ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AFFAIRES COURANTES ORDINAIRES TABLING OF DOCUMENTS DÉPÔT DE DOCUMENTS Pursuant to Standing Order 32(2), Mr. Lukiwski (Parliamentary Conformément à l'article 32(2) du Règlement, M. Lukiwski Secretary to the Leader of the Government in the House of (secrétaire parlementaire du leader du gouvernement à la Chambre Commons) laid upon the Table, — Government responses, des communes) dépose sur le Bureau, — Réponses du pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), to the following petitions: gouvernement, conformément à l’article 36(8) du Règlement, aux pétitions suivantes : — Nos. 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, — nos 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, 402- 402-1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 402- 402-1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 and 402-1513 1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 et 402-1513 au sujet du concerning the Employment Insurance Program. — Sessional régime d'assurance-emploi. — Document parlementaire no 8545- Paper No. 8545-403-1-01; 403-1-01; — Nos. 402-1129, 402-1174 and 402-1268 concerning national — nos 402-1129, 402-1174 et 402-1268 au sujet des parcs parks. — Sessional Paper No. 8545-403-2-01; nationaux. — Document parlementaire no 8545-403-2-01; — Nos. -

September 91 H, 2014 the Honourable Kathleen Wynne

TOWNSHIP OF NAIRN AND HYMAN 64 Mcintyre Street • Nairn Centre, Ontario • POM 2LO • (705) 869-4232 • Fax: (705) 869-5248 Established: March 7, 1896 Office of the Clerk Treasurer, CAO E-mail: [email protected] web page: www.nairncentre.ca 1 September 9 h, 2014 The Honourable Kathleen Wynne Premier of Ontario Legislative Building Queen's Park Toronto, Ontario M7A 1A1 Re: Power Dam Special Payment Program Dear Premier Wynne: Please be advised that our Council adopted the following motion at their meeting of September 2nd, 2014: RESOLUTION# 2014-12-189 MOVED BY: Edward Mazey SECONDED BY: Charlene Y. Martel WHEREAS: in December 2000, the Province of Ontario passed the Continued Protection for Property Taxpayers Act, (Bill 140); and WHEREAS: the Continued Protection for Property Taxpayers Act, among other matters, exempted certain hydro-electric stations and poles & wires from municipal taxation as of January 1, 2001; and WHEREAS: the Continued Protection for Property Taxpayers Act removed the right and authority of affected municipalities across the Province to levy property tax notices to hydro-electric stations, poles & wires, representing significant taxable property assessment; and WHEREAS: the Province of Ontario replaced the above noted rights and authority to tax hydro-electric stations, poles & wires with a compensatory payment, known as the Power Dam Special Payment Program, equivalent to the taxes levied on the subject structures in 2000; and Premier of Ontario 1 September 9 h, 2014 Page2 WHEREAS: the amount of payments -

Public Comments

Timestamp Meeting Date Agenda Item First and Last Name Zip Code Representing Comments It is inappropriate to use an obviously biased company for Arizona’s redistricting mapping process. Bernie Sanders and Barack Obama should have zero say in what our maps look like, and these companies are funded by them at the national level. We want you to hire the National Demographics Corporation – Douglas Johnson in order to assure Arizonans of fair representation and elections. The “Independent” Review Council should make amends for ten years of incompetence and corruption. The commissioners met as many as five times at the home of the AZ 4/27/2021 9:12:25 April 27, 2021 Redistricting Marta 85331 Democratic Party’s Executive Director! It is inappropriate to use an obviously biased company for Arizona’s redistricting mapping process. Bernie Sanders and Barack Obama should have zero say in what our maps look like, and these companies are funded by them at the national level. We want you to hire the National Demographics Corporation – Douglas Johnson in order to assure Arizonans of fair representation and elections. The “Independent” Review Council should make amends for ten years of incompetence Redistricting and corruption. The commissioners met as many as five times at the home of the AZ 4/27/2021 9:12:47 April 27, 2021 Company Michael MacBan 85331 Democratic Party’s Executive Director! I would l ke to request that the company to be hired is the National Demographics Corporation – Douglas Johnson, in order to assure Arizonans fair representation and redistricting elections. mapping It would be inappropriate to use a biased company for the redistricting mapping process. -

Christian Nonprofit Ceos:Ethical Idealism, Relativism, and Motivation

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Dissertations Graduate School Spring 2016 Christian Nonprofit EC Os:Ethical Idealism, Relativism, and Motivation Sharlene Garces Baragona Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/diss Part of the Applied Behavior Analysis Commons, Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Commons, and the Industrial and Organizational Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Baragona, Sharlene Garces, "Christian Nonprofit EC Os:Ethical Idealism, Relativism, and Motivation" (2016). Dissertations. Paper 100. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/diss/100 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHRISTIAN NONPROFIT CEOS: ETHICAL IDEALISM, RELATIVISM, AND MOTIVATION A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Educational Leadership Doctoral Program Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education By Sharlene Sameon Garces Baragona May 2016 I humbly dedicate this work to my Creator, Lord of heaven and earth, Constant Provider, Ultimate Moral Law Giver, Loving Savior, and the Great I Am. Almighty God, You alone are worthy of all honor, glory, and praise. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Lord has blessed me with wonderful people who helped me complete this doctoral degree. I could not take this journey without Earnest, my loving husband and best friend, by my side. God gave me more than I asked when Earnest came into my life. I have been very fortunate to have an excellent team of mentors who challenged and inspired me to succeed. -

ONLINE INCIVILITY and ABUSE in CANADIAN POLITICS Chris

ONLINE INCIVILITY AND ABUSE IN CANADIAN POLITICS Chris Tenove Heidi Tworek TROLLED ON THE CAMPAIGN TRAIL ONLINE INCIVILITY AND ABUSE IN CANADIAN POLITICS CHRIS TENOVE • HEIDI TWOREK COPYRIGHT Copyright © 2020 Chris Tenove; Heidi Tworek; Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions, University of British Columbia. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. CITATION Tenove, Chris, and Heidi Tworek (2020) Trolled on the Campaign Trail: Online Incivility and Abuse in Canadian Politics. Vancouver: Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions, University of British Columbia. CONTACT DETAILS Chris Tenove, [email protected] (Corresponding author) Heidi Tworek, [email protected] CONTENTS AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES ..................................................................................................................1 RESEARCHERS ...............................................................................................................................1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................5 FACING INCIVILITY IN #ELXN43 ....................................................................................................8 -

Great Expectations: the Experienced Credibility of Cabinet Ministers and Parliamentary Party Leaders

Great expectations: the experienced credibility of cabinet ministers and parliamentary party leaders Sabine van Zuydam [email protected] Concept, please do not cite Paper prepared for the NIG PUPOL international conference 2016, session 4: Session 4: The Political Life and Death of Leaders 1 In the relationship between politics and citizens, political leaders are essential. While parties and issues have not become superfluous, leaders are required to win support of citizens for their views and plans, both in elections and while in office. To be successful in this respect, credibility is a crucial asset. Research has shown that credible leaders are thought to be competent, trustworthy, and caring. What requires more attention is the meaning of competent, caring, and trustworthy leaders in the eyes of citizens. In this paper the question is needed to be credible according to citizens in different leadership positions, e.g. cabinet ministers and parliamentary party leaders. To answer this question, it was studied what is expected of leaders in terms of competence, trustworthiness, and caring by conducting an extensive qualitative analysis of Tweets and newspaper articles between August 2013 and June 2014. In this analysis, four Dutch leadership cases with a contrasting credibility rating were compared: two cabinet ministers (Frans Timmermans and Mark Rutte) and two parliamentary party leaders (Emile Roemer and Diederik Samsom). This analysis demonstrates that competence relates to knowledgeability, decisiveness and bravery, performance, and political strategy. Trustworthiness includes keeping promises, consistency in views and actions, honesty and sincerity, and dependability. Caring means having an eye for citizens’ needs and concern, morality, constructive attitude, and no self-enrichment. -

January 27, 2020

Queen’s Park Today – Daily Report January 27, 2020 Quotation of the day “Peace room.” What the premier’s office says it is calling its logistics office dealing with teachers’ strikes. Today at Queen’s Park On the schedule There are three more weeks left of the winter break. The house will reconvene on Tuesday, February 18, 2020. Premier watch Premier Doug Ford was in Mississauga Friday to re-announce funding for community policing. Specifically, the Peel Regional Police is getting $20.5 million from the Community Safety and Policing grant program, a $195-million envelope the PCs announced in mid-December. In Peel, some of the cash will go towards more neighbourhood watch services, police town halls and “cultural community outreach.” "My message to the criminals that are watching us now: we are coming for you, we are going to find you and we are going to lock you up for a long time,” Ford said at the news conference, which featured a well-armed police backdrop. Solicitor General Sylvia Jones, Attorney General Doug Downey, local PC MPPs and ex-PC leader-turned-mayor-of-Brampton Patrick Brown were also in tow. Brown and Ford had their first official sit-down since Ford took office at the Peel police station where the announcement took place. The pair discussed crime, CCTV cameras, courthouse resources and health care, according to the mayor. “I appreciate the cooperative tone,” Brown tweeted, alongside a “prayer hands” emoji. Ford defended the decision to appoint Toronto police constable Randall Arsenault to the Ontario Human Rights Commission, despite the fact he was not part of the official candidate selection process. -

COPE 343 June 6, 2019 for IMMEDIATE RELEASE One Year

June 6, 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE One year after the Ford government’s election, people want answers from Conservative MPPs TORONTO — This week, people across Toronto and Ontario are taking action to put pressure on the Conservatives to reverse a series of unpopular cuts that have brought Premier Doug Ford’s popularity to record lows. Activities across the region are shining a light on the issues. Events include school walk-ins at over 300 schools on Thursday, “lunch and learn” events in workplaces and demonstrations in public spaces on Friday, and community canvasses in eleven Conservative ridings on Saturday. The events are part of ongoing grassroots efforts led by community- and labour-based organizations to inform and empower people to take action and influence government. Toronto & York Region Labour Council, Progress Toronto, Urban Alliance on Race Relations, and the Campaign for Public Education are just a few groups who have organized locally, helping tens of thousands of people to make their voices heard. “One year after the election, the people of this province are shocked with the poor decisions this government is making. Taking away rights of temp agency workers, rolling back the minimum wage increase for over a million Ontarians and imposing reductions of real earnings of another million front- line workers—there is a pattern here. It’s called abuse of power,” said John Cartwright, President of the Toronto & York Region Labour Council. “Since the Conservatives never released a proper platform during last year’s election, most of their policies have been a complete surprise to Ontarians. People did not vote for these cuts, or the undermining of democracy every day.” Programs and services like education, child care, and public health are on the chopping block. -

FEMA FOIA Log – 2018

Mirandra Abrams, Monique any and all records concerning clients. Kindly provide our office with 10/4/2017 Sambursky a complete copy of clients entire file as it pertains as it pertains to Slone Sklarin Inquiry Number (b) (6) ; Voucher Number (b) (6) ; Payee Verveniotis Reference Number (b) (6) in your possession. 2017-FEFO-02138 - Masters, Mark all contract documents related to temporary staffing services 10/5/2017 contracts for emergency call center support for FEMA in the last five 2017-FEFO-02177 (5) years 2017-FEFO-02187 - (b) (6) all files, correspondence, or other records concerning yourself 10/6/2017 Dallas News Benning, Tom 1) All active FEMA contracts for manufactured housing units. 2) All 10/13/2017 active FEMA individual assistance/technical assistance contracts (IATACs). 3) All pre-event contracts for debris removal that are overseen by FEMA Region 6. 4) All pre-event contracts for housing assistance that are overseen by FEMA Region 6. 5) All noncompetitive disaster relief contracts approved by FEMA since August 14, 2017. 6) All non-local disaster relief contracts approved by FEMA since August 14, 2017, including the written justification 2017-FEFO-02214 for choosing a non-local vendor. FCI Keys, Clay a copy of any and all records related to [FEMA's] response to 10/23/2017 SEAGOVILLE hurricane Katrina, including all memoranda, communications and records of any kind and from any source from August 29, 2005 to 2012. (Date Range for Record Search: From 8/29/2005 To 2017-FEFO-02239 12/1/2012) - (b) (6) Any files related to yourself (Date Range for Record Search: From 10/24/2017 2017-FEFO-02240 1/1/2000 To 9/11/2017) - McClain, Don every individual who has requested assistance by FEMA from both 10/31/2017 Hurricane Irma and Harvey.