THE Iffilville REVIVAL a Study of Twentieth Century Criticism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christian Nonprofit Ceos:Ethical Idealism, Relativism, and Motivation

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Dissertations Graduate School Spring 2016 Christian Nonprofit EC Os:Ethical Idealism, Relativism, and Motivation Sharlene Garces Baragona Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/diss Part of the Applied Behavior Analysis Commons, Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Commons, and the Industrial and Organizational Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Baragona, Sharlene Garces, "Christian Nonprofit EC Os:Ethical Idealism, Relativism, and Motivation" (2016). Dissertations. Paper 100. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/diss/100 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHRISTIAN NONPROFIT CEOS: ETHICAL IDEALISM, RELATIVISM, AND MOTIVATION A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Educational Leadership Doctoral Program Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education By Sharlene Sameon Garces Baragona May 2016 I humbly dedicate this work to my Creator, Lord of heaven and earth, Constant Provider, Ultimate Moral Law Giver, Loving Savior, and the Great I Am. Almighty God, You alone are worthy of all honor, glory, and praise. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Lord has blessed me with wonderful people who helped me complete this doctoral degree. I could not take this journey without Earnest, my loving husband and best friend, by my side. God gave me more than I asked when Earnest came into my life. I have been very fortunate to have an excellent team of mentors who challenged and inspired me to succeed. -

Antipascha—Saint Thomas Sunday

Holy Ghost Orthodox Church 714 Westmoreland Avenue PO Box 3 Slickville, PA 15684-0003 www.holyghostorthodoxchurch.org Very Rev. Father Robert Popichak, Pastor 23 Station Street Carnegie, PA 15106-3014 [412] 279-5640 home [412] 956-6626 cell ANTIPASCHA—SAINT THOMAS SUNDAY ON THE MEND: Please keep the following parishioners and others in your prayers for recovery from their illnesses and injuries: Archbishop Daniel, Metropolitan Antony, Metropolitan Yurij, Anastasia [Metropolitan Yurij’s mom], Metropolitan Theodosius [OCA], Archbishop Jovan, Bishop Robert, Father George & Pani Lillian Hnatko, Father Jakiw Norton, Father Paul Stoll, Father Igor Soroka, Father Joseph Kopchak, Father Elias Warnke, Father Nestor Kowal, Father George Yatsko, Father Paul Bigelow, Father Emilian Balan, Father John & Pani Mary Anne Nakonachny, Father Steve Repa, Protopresbyter William Diakiw, Archpriest Dionysi Vitali, Protodeacon Joseph Hotrovich, Father Adam Yonitch, Pani-Dobrodijka Sonia Diakiw, Father Paisius McGrath, Father Michael Smolynec, Father Lawrence & Matushka Sophia Daniels, Father Joe Cervo, Father John Harrold [Saint Sylvester], Joshua Agosto and his family, Eva Malesnick, Nick Behun, Grace Holupka, Joseph Sliwinsky, Gary & Linda Mechtly, Evelyn Misko, Jeanne Boehing, Alex Drobot, Rachelle, Jane Golofski, Doug Diller, Harry Krewsun, Mary Alice Babcock, Dorie Kunkle, Andrea, & Melissa [Betty O’Masta’s relatives], Mary Evelyn King, Sam Wadrose, Isabella Olivia Lindgren, Ethel Thomas, Donna, Erin, Michael Miller, Grace & Owen Ostrasky, Patti Sinecki, -

Great Revival Stories

Great Revival Stories from the Renewal Journal Geoff Waugh (Editor) Copyright © Geoff Waugh, 2014 Compiled from two books: Best Revival Stories and Transforming Revivals See details on www.renewaljournal.com Including free digital revival books ISBN-13: 978-1466384262 ISBN-10: 1466384263 Printed by CreateSpace, Charleston, SC, USA, 2011 Renewal Journal Publications www.renewaljournal.com PO Box 2111, Mansfield, Brisbane, Qld, 4122 Australia Power from on High Contents Introduction: “Before they call, I will answer” Part 1: Best Revival Stories 1 Power from on High, by John Greenfield 2 The Spirit told us what to do, by Carl Lawrence 3 Pentecost in Arnhem Land, by Djiniyini Gondarra 4 Speaking God’s Word, by David Yonggi Cho 5 Worldwide Awakening, by Richard Riss 6 The River of God, by David Hogan Part 2: Transforming Revivals 7 Solomon Islands 8 Papua New Guinea 9 Vanuatu 10 Fiji 11 Snapshots of Glory, by George Otis Jr 12 The Transformation of Algodoa de Jandaira Conclusion Appendix: Renewal and Revival Books Expanded Contents These chapters give details of many events 5 Worldwide Awakening, by Richard Riss Argentina Rodney Howard-Browne Kenneth Copeland Karl Strader Bud Williams Oral Roberts Charles and Frances Hunter Ray Sell Mona And Paul Johnian Jerry Gaffney The Vineyard Churches Randy Clark Argentina as a Prelude to the “Toronto Blessing” John Arnott Worldwide Effects of the Vineyard Revival Impact upon the United Kingdom Holy Trinity Brompton Sunderland Christian Centre Vietnam and Cambodia Melbourne, Florida Revival Mott Auditorium, -

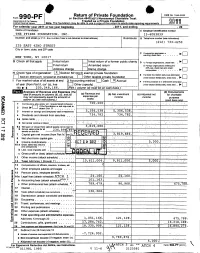

Return of Private Foundation CT' 10 201Z '

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirem M11 For calendar year 20 11 or tax year beainnina . 2011. and ending . 20 Name of foundation A Employer Identification number THE PFIZER FOUNDATION, INC. 13-6083839 Number and street (or P 0 box number If mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) (212) 733-4250 235 EAST 42ND STREET City or town, state, and ZIP code q C If exemption application is ► pending, check here • • • • • . NEW YORK, NY 10017 G Check all that apply Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D q 1 . Foreign organizations , check here . ► Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address chang e Name change computation . 10. H Check type of organization' X Section 501( exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 ( a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation q 19 under section 507(b )( 1)(A) , check here . ► Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method Cash X Accrual F If the foundation is in a60-month termination of year (from Part Il, col (c), line Other ( specify ) ---- -- ------ ---------- under section 507(b)(1)(B),check here , q 205, 8, 166. 16) ► $ 04 (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis) Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (The (d) Disbursements total of amounts in columns (b), (c), and (d) (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net for charitable may not necessanly equal the amounts in expenses per income income Y books purposes C^7 column (a) (see instructions) .) (cash basis only) I Contribution s odt s, grants etc. -

The Poetry of Alice Meynell and Its Literary Contexts, 1875-1923 Jared Hromadka Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 The al ws of verse : the poetry of Alice Meynell and its literary contexts, 1875-1923 Jared Hromadka Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hromadka, Jared, "The al ws of verse : the poetry of Alice Meynell and its literary contexts, 1875-1923" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1246. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1246 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE LAWS OF VERSE: THE POETRY OF ALICE MEYNELL AND ITS LITERARY CONTEXTS, 1875-1923 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Jared Hromadka B.A., Louisiana State University, 2004 M.A., Auburn University, 2006 August 2013 for S. M. and T. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Special thanks is due to Dr. Elsie Michie, without whose encouragement and guidance this project would have been impossible. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS..............................................................................................................iii -

Is Your Church Revival Ready?

a publication of Life Action Ministries Is Your Church Revival Ready? The Four-Question Challenge Fall 2013 Volume 44, Issue 3 www.LifeAction.org/revive CONTENTS FEATURES 6 Is Your Church Revival Ready? Dan Jarvis 8 Discovering a New Normal 6 Matt Bennett Breaking Out of Busy Christianity 12 Gregg Simmons 16 Altars That Transform Nations Mark Daniels 20 Reaching the Unreached 8 12 Samuel Stephens COLUMNS 3 Spirit of Revival The New Life of Jesus Byron Paulus 16 5 Conversations Do You Pray? Del Fehsenfeld III Executive Director: Byron Paulus Senior Editor: Del Fehsenfeld III Managing Editor: Daniel W. Jarvis Assistant Editor: Kim Gwin 25 From the Heart Creative Director: Aaron Paulus Art Director: Tim Ritter Don’t Lose the Intimacy Senior Designer: Thomas A. Jones Nancy Leigh DeMoss Graphic Designer: Ben Cabe Photography: istockphoto.com: tihov; Lightsource.com: Sarah & Rocky, Shaun Menary, Alan Perera, Paul Go Images, & 31 Next Step Mario Mattei Do or Die Dan Jarvis Volume 44, Issue 3 Copyright © 2013 by Life Action Ministries. All rights reserved. PERSPECTIVES Revive magazine is published quarterly as God provides, and made available at no cost to those who express a genuine burden for revival. It is financially 26 Real World supported by the gifts of God’s people as they respond to the promptings of His How Is God Working? Spirit. Its mission is to ignite movements of revival and authentic Christianity. 28 Making It Personal Life Action does not necessarily endorse the entire philosophy and ministry of Apply principles discussed in this issue. all its contributing writers. -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Ralph

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Ralph H. Records Collection Records, Ralph Hayden. Papers, 1871–1968. 2 feet. Professor. Magazine and journal articles (1946–1968) regarding historiography, along with a typewritten manuscript (1871–1899) by L. S. Records, entitled “The Recollections of a Cowboy of the Seventies and Eighties,” regarding the lives of cowboys and ranchers in frontier-era Kansas and in the Cherokee Strip of Oklahoma Territory, including a detailed account of Records’s participation in the land run of 1893. ___________________ Box 1 Folder 1: Beyond The American Revolutionary War, articles and excerpts from the following: Wilbur C. Abbott, Charles Francis Adams, Randolph Greenfields Adams, Charles M. Andrews, T. Jefferson Coolidge, Jr., Thomas Anburey, Clarence Walroth Alvord, C.E. Ayres, Robert E. Brown, Fred C. Bruhns, Charles A. Beard and Mary R. Beard, Benjamin Franklin, Carl Lotus Belcher, Henry Belcher, Adolph B. Benson, S.L. Blake, Charles Knowles Bolton, Catherine Drinker Bowen, Julian P. Boyd, Carl and Jessica Bridenbaugh, Sanborn C. Brown, William Hand Browne, Jane Bryce, Edmund C. Burnett, Alice M. Baldwin, Viola F. Barnes, Jacques Barzun, Carl Lotus Becker, Ruth Benedict, Charles Borgeaud, Crane Brinton, Roger Butterfield, Edwin L. Bynner, Carl Bridenbaugh Folder 2: Douglas Campbell, A.F. Pollard, G.G. Coulton, Clarence Edwin Carter, Harry J. Armen and Rexford G. Tugwell, Edward S. Corwin, R. Coupland, Earl of Cromer, Harr Alonzo Cushing, Marquis De Shastelluz, Zechariah Chafee, Jr. Mellen Chamberlain, Dora Mae Clark, Felix S. Cohen, Verner W. Crane, Thomas Carlyle, Thomas Cromwell, Arthur yon Cross, Nellis M. Crouso, Russell Davenport Wallace Evan Daview, Katherine B. -

The Nineteenth Century Wasteland: the Void in the Works of Byron, Baudelaire, and Melville

The Woman's College of The University of North Carolina LIBRARY COLLEGE COLLECTION cq no. 636 Gift of MARY GATES BRITTAIN BRITTAIN, MARY GATES. The Nineteenth Century Wasteland: The Void In The Works Of Byron, Baudelaire, And Melville. (1969) Directed by: Dr. Arthur W. Dixon. pp. I**1* The theme of the twentieth century "wasteland" began with T. S. Eliot's influential poem, and has reached its present culmination point in the literature of the Absurd. In a wasteland or an Absurd world, man is out of harmony with his universe, with his fellow man, and even with himself. There is Nothingness in the center of the universe, and Noth- ingness in the heart or center of man as well. "God Is Dead" in the wasteland and consequently it is an Iconoclastic world without religion, and without love; a world of aesthetic and spiritual aridity and ster- ility. Most writers, critics, and students of literature are familiar with the concept of the wasteland, but many do not realize that this is not a twentieth century thematic phenomenon. The contemporary wasteland has its parallel in the early and middle nineteenth century with the Romantics; with such writers as Byron, Baudelaire, and Melville. The disillusionment of western man at the end of World War I was similar in many respects to that experienced by the Romantics at the end of the French Revolution. Furthermore, the break-up of the old order, and the disappearance of iod from the cosmos in the closing years of the eighteenth century, along with the shattering of many illusions by the discoveries of science, the loss of both religious and secular values, and the break-down in the political order in the early nineteenth century, left man alienated, isolated, homeless, and friend- less. -

Service Books of the Orthodox Church

SERVICE BOOKS OF THE ORTHODOX CHURCH THE DIVINE LITURGY OF ST. JOHN CHRYSOSTOM THE DIVINE LITURGY OF ST. BASIL THE GREAT THE LITURGY OF THE PRESANCTIFIED GIFTS 2010 1 The Service Books of the Orthodox Church. COPYRIGHT © 1984, 2010 ST. TIKHON’S SEMINARY PRESS SOUTH CANAAN, PENNSYLVANIA Second edition. Originally published in 1984 as 2 volumes. ISBN: 978-1-878997-86-9 ISBN: 978-1-878997-88-3 (Large Format Edition) Certain texts in this publication are taken from The Divine Liturgy according to St. John Chrysostom with appendices, copyright 1967 by the Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of America, and used by permission. The approval given to this text by the Ecclesiastical Authority does not exclude further changes, or amendments, in later editions. Printed with the blessing of +Jonah Archbishop of Washington Metropolitan of All America and Canada. 2 CONTENTS The Entrance Prayers . 5 The Liturgy of Preparation. 15 The Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom . 31 The Divine Liturgy of St. Basil the Great . 101 The Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts. 181 Appendices: I Prayers Before Communion . 237 II Prayers After Communion . 261 III Special Hymns and Verses Festal Cycle: Nativity of the Theotokos . 269 Elevation of the Cross . 270 Entrance of the Theotokos . 273 Nativity of Christ . 274 Theophany of Christ . 278 Meeting of Christ. 282 Annunciation . 284 Transfiguration . 285 Dormition of the Theotokos . 288 Paschal Cycle: Lazarus Saturday . 291 Palm Sunday . 292 Holy Pascha . 296 Midfeast of Pascha . 301 3 Ascension of our Lord . 302 Holy Pentecost . 306 IV Daily Antiphons . 309 V Dismissals Days of the Week . -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS Benjamin Franklin, Pennsylvania, and the First Nations: The Treaties of 1736–62. Edited by SUSAN KALTER. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006. xiv, 453 pp. Illustrations, notes, glossary, index. $45.) Between 1736 and 1762, Benjamin Franklin published thirteen treaties made between Pennsylvania and the Six Nations Iroquois and their native allies, including the Lenapes and the Shawnees. At these treaty negotiations, leaders from different cultures gathered to determine vital issues of war and peace, regulate intercultural exchange, and seek justice from one another. William Penn’s secretary, James Logan, noted that the 1736 treaty talks in Philadelphia were conducted “in the presence and hearing of some Thousands of our People” (p. 56). Treaty negotiations were public spectacles in an age without many large- scale events. Of enormous importance in the eighteenth century, the treaties were largely forgotten in the nineteenth century, only to be rediscovered in the early twentieth century as a compelling and uniquely American literary form. In 1938, Julian P.Boyd republished the treaties in a single volume with an introduction by Carl Van Doren. According to Van Doren, the “stately folios” printed by Franklin were “after two hundred years the most original and engaging documents of their century in America” (Indian Treaties Printed by Benjamin Franklin, vii). Boyd reproduced the treaties in facsimile on legal-sized paper, in a beautiful edition of five hundred numbered copies. These large, unwieldy, and expensive books have rested in the special collections of major research libraries, often with their pages uncut and unread. This new edition by Susan Kalter will make these important documents much more accessible and available. -

About Natstand Family Documents

natstand: last updated 24/02/2018 URL: www.natstand.org.uk/pdf/MennellHT000.pdf Root person: Mennell, Henry Tuke (1835 - 1923) Description: Family document Creation date: 2018 January 26 Prepared by: Richard Middleton Notes: Press items reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk) About Natstand family documents: A Natstand family document is intended to provide background information concerning the family of a deceased naturalist. It is hoped that such information will form a framework which will help interpret their surviving correspondence, specimens and records. In some cases it will also give an insight into the influences on their early lives and the family constraints within which they worked and collected. We have found that published family data concerning individuals rarely contain justification for dates and relationships and not infrequently contain errors which are then perpetuated. The emphasis in Natstand family documents will be on providing references to primary sources, whenever possible, which will be backed-up with transcriptions. Although a Natstand biography page will always carry a link to a family document, in many cases these documents will be presented without any further biographical material. We anticipate that this will occur if the person is particularly well known or is someone we are actively researching or have only a peripheral interest in. The following conventions are used: Any persons in the family tree with known natural history associations will be indicated in red type. Any relationships will be to the root naturalist unless otherwise stated. Dates are presented Year – Month – Day e.g. 1820 March 9 or 1820.3.9 1820 March or 1820.3 Dates will be shown in bold type if a reliable reference is presented in the document. -

Melville Revival" Author(S): CATHERINE GANDER Source: Journal of American Studies, Vol

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by MURAL - Maynooth University Research Archive Library Muriel Rukeyser, America, and the "Melville Revival" Author(s): CATHERINE GANDER Source: Journal of American Studies, Vol. 44, No. 4 (November 2010), pp. 759-775 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the British Association for American Studies Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25790528 Accessed: 19-08-2019 10:36 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25790528?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Cambridge University Press, British Association for American Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of American Studies This content downloaded from 149.157.61.157 on Mon, 19 Aug 2019 10:36:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Journal of American Studies, 44 (2010), 4, 759?77$ ? Cambridge University Press 2010 doi:io.ioi7/Soo2i8758o999i435 First published online 5 February 2010 Muriel CATHERINE GANDER Abstract.