Defining Suburbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

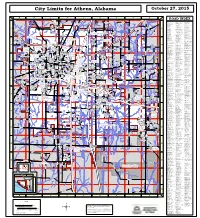

City Limits Map (PDF)

City Limits for Athens, Alabama October 27, 2015 M N O P Q R S T U Ella Grace M Al Hwy 127 Way o Sugar Hill 206 o Rd r ROAD INDEX Ln e Kimzy Carr Rd Sardis Springs s v i ielding l Johnson St F l # FRANK ST, S-15 PALMER ST, N-17 J Berzett Rd e L d o Ruff Cemetery R n R FRAZIER ST, P-15, P-14 PAMELA DR, M-13 r 10TH AV, O-14 d d Wood Ln d a 10TH ST, O-16 FREEMAN AV, P-16, Q-16 PANSY CIR, P-15 n R 12TH ST, O-16, N-16 FRENCH FARMS BLVD, P-16 PARIS LN, P-13 n ris Ln o 14TH ST, N-16 FRENCH WAY, P-16 PARK LN, N-16 Pa t k Muddy Creek l 1ST AV, O-15 FYNE DR, R-15 PARK PL, P-16 E 17 1ST ST, O-15 G PAT INGRAM ST, O-16 127 2ND AV, O-15 GABLES END DR, U-17 PAT ST, N-15 Looney Rd C 2ND ST, O-16 GALE LN, O-15 PATTOCK CT, N-15 Airfield St op I 65 N el A an 3RD AV, O-15 GARDENIA MANOR, U-20 PATTON ST, O-15 HeronDr Holt Rd r d c Rd 3RD ST, O-16 GARRETT DR, P-14 PAULA ST, N-15 13 Runway St t 13 i Airport Rd c 4TH AV, O-15 GARY REDUS DR, P-20 PAVILION CT, R-18 ClemAcre L GEORGE BRALY WAY, Q-20, R- PEACHTREE ST, O-15 n 4TH ST, O-16 Broadwater Pvt Dr Compton Rd E 5TH AV, O-15, N-15 21 PEETE RD, P-23, Q-23 18 260 d Jw Bobo Rd 5TH ST, O-16 GEORGE WASHINGTON ST, P- PEPPER RD, R-16, S-16, U- g 230 th Panther e r o 16, T-16 w r 6TH AV, O-14 20, P-21 w D Branch o t 6TH ST, O-16 GEORGIE EDITH LN, S-15 PHYLLIS ST, S-14 o 258 206. -

Fuori Le Mura: the Productive Compartmentaliztion of the Megalopolis

Fuori le Mura: The productive compartmentaliztion of the megalopolis Joshua Stein Woodbury University Fuori le Mura is a radical speculative proposal provoking inquiry into right- sizing the contemporary megalopolis. Through a size comparison of vari- ous urban configurations with strictly defined perimeter boundaries, from the Italian city-state to the urban growth boundaries exemplified in con- temporary cities like Portland, OR, a cohesive urban identity and scale is The Walled City defined. Could “walled” mega-enclaves (scaled to match the ideal city size Medieval Siena’s wall operates as more than a simple fortification against the outside of Portland) create manageable urban nodes with a territory of free experi- world. Instead it fosters a complex negotiation between the extra-urban activities still very much networked to those inside the walls. mentation replacing suburbia. Fuori le Mura—Outside the Walls—is a proposal for Los Angeles that draws a dividing line between two complementary modes of living, rein- stating the historical concept of Urbs vs. Rure. No longer prolonging the corrosive dynamic between City and Suburb, where the suburb is simul- taneously culturally subservient to the city and parasitic in its consump- tion of resources, Fuori le Mura instead proposes two different modes of sustainable development and resource management that operate in par- allel. Outside the walls the ultimate fantasy of “no government” prevails— the obvious repercussions being the lack of infrastructure or utilities. The only dictates outside the walls are proscriptive: no impact/no emissions. Beyond this anything is possible. Within the walls infrastructure and utili- ties are heavily regulated, providing inhabitants with easy, prescriptive models for sustainable living. -

BUILDING from SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg After Apartheid

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH 471 DOI:10.1111/1468-2427.12180 — BUILDING FROM SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg after Apartheid claire w. herbert and martin j. murray Abstract By the start of the twenty-first century, the once dominant historical downtown core of Johannesburg had lost its privileged status as the center of business and commercial activities, the metropolitan landscape having been restructured into an assemblage of sprawling, rival edge cities. Real estate developers have recently unveiled ambitious plans to build two completely new cities from scratch: Waterfall City and Lanseria Airport City ( formerly called Cradle City) are master-planned, holistically designed ‘satellite cities’ built on vacant land. While incorporating features found in earlier city-building efforts, these two new self-contained, privately-managed cities operate outside the administrative reach of public authority and thus exemplify the global trend toward privatized urbanism. Waterfall City, located on land that has been owned by the same extended family for nearly 100 years, is spearheaded by a single corporate entity. Lanseria Airport City/Cradle City is a planned ‘aerotropolis’ surrounding the existing Lanseria airport at the northwest corner of the Johannesburg metropole. These two new private cities differ from earlier large-scale urban projects because everything from basic infrastructure (including utilities, sewerage, and the installation and maintenance of roadways), -

The Hub's Metropolis: a Glimpse Into Greater Boston's Development

James C. O’Connell, “The Hub’s Metropolis: Greater Boston’s Development” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 42, No. 1 (Winter 2014). Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/ number/ date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.wsc.ma.edu/mhj. 26 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2014 Published by The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 7x9 hardcover, 326 pp., $34.95. To order visit http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/hubs-metropolis 27 EDITor’s choicE The Hub’s Metropolis: A Glimpse into Greater Boston’s Development JAMES C. O’CONNELL Editor’s Introduction: Our Editor’s Choice selection for this issue is excerpted from the book, The Hub’s Metropolis: Greater Boston’s Development from Railroad Suburbs to Smart Growth (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2013). All who live in Massachusetts are familiar with the compact city of Boston, yet the history of the larger, sprawling metropolitan area has rarely been approached as a comprehensive whole. As one reviewer writes, “Comprehensive and readable, James O’Connell’s account takes care to orient the reader in what is often a disorienting landscape.” Another describes the book as a “riveting history of one of the nation’s most livable places—and a roadmap for how to keep it that way.” James O’Connell, the author, is intimately familiar with his topic through his work as a planner at the National Park Service, Northeast Region, in Boston. -

Satellite Towns

24 Satellite Towns Introduction 'Satellite town' was a term used in the year immediately after the World War I as an alternative to Garden City. It subsequently developed a much wider meaning to include any town that is closely related to or dependent on a larger city. The first specific usage of the word ‘satellite town’ was in 1915 by G.R. Taylor in ‘ Satellite Cities’ referring to towns around Chicago, St. Louis and other American cities where industries had escaped congestion and crafted manufacturer’s town in the surrounding area. The new town is planned and built to serve a particular local industry, or as a dormitory or overspill town for people who work in and nearby metropolis. Satellite Town, can also be defined as a town which is self contained and limited in size, built in the vicinity of a large town or city and houses and employs those who otherwise create a demand for expansion of the existing settlement, but dependent on the parent city to some extent for population and major services. A distinction is made between a consumer satellite (essentially a dormitory suburb with few facilities) and a production satellite (with a capacity for commercial, industrial and other production distinct from that of the parent town, so a new town) town or satellite city is a concept of urban planning and referring to a small or medium-sized city that is near a large metropolis, but predates that metropolis suburban expansion and is atleast partially independent from that metropolis economically. CITIES, URBANISATION AND URBAN SYSTEMS 414 Satellite and Dormitory Towns The suburb of an urban centre where due to locational advantage the residential, industrial and educational centres are developed are known as "satellite or dormitory towns." It has a benefit of providing clean environment and spacious ground for residential and industrial expansion. -

![City Against Suburb: the Culture Wars in an American Metropolis [Book Review]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5978/city-against-suburb-the-culture-wars-in-an-american-metropolis-book-review-285978.webp)

City Against Suburb: the Culture Wars in an American Metropolis [Book Review]

Haverford College Haverford Scholarship Faculty Publications Political Science 2001 City Against Suburb: The Culture Wars in an American Metropolis [book review] Stephen J. McGovern Haverford College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.haverford.edu/polisci_facpubs Repository Citation McGovern, Stephen. City Against Suburb: The Culture Wars in an American Metropolis, Joseph A. Rodriguez, Pacific Historical Review, 70(2): 332-334, May 2001. This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science at Haverford Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Haverford Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reviews of Books Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 70, No. 2 (May 2001), pp. 304-351 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/phr.2001.70.2.304 . Accessed: 29/03/2013 12:19 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Pacific Historical Review. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 165.82.168.47 on Fri, 29 Mar 2013 12:19:39 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Reviews of Books The World That Trade Created: Society, Culture, and the World Economy, 1400 to the Present . -

MEGALOPOLIS MEGALOPOLIS Megalopolis at Night

3/7/2013 MEGALOPOLIS • Term used to describe any large urban Regional Landscapes of the area created by the growth toward each United States and Canada other and eventual merging of two or MEGALOPOLIS more cities. • The French geographer Jean Gottman Prof. Anthony Grande adopted the term in 1961 for the title of his ©AFG 2013 book, “Megalopolis: The Urbanized Northeastern Seaboard of the United States.” Megalopolis Megalopolis at Night When used with a capital “M”, the term denotes the almost unbroken urban Megalopolis development that extends extends over 500 from north of Boston, MA miles from the to counties south of Wash- northern fringe of ington, DC (from Portsmouth, the Boston metro Boston NH approaching Richmond, VA). area (in NH) to Washington, DC New York City metro area. With a lower case “m” the Philadelphia term is applied to any string Some people have of adjoining very large it extending to Baltimore cities. Richmond, VA. Washington Richmond 4 LANDSCAPES of Megalopolis From the beginning: SETTLEMENT Includes large cities, small towns and rural areas where most of the A place where one people reside in an urban place. person or a group of people live. Settlements are differentiated on the basis of size = number of people present spacing = distance from each other function = reason for people grouping there 6 1 3/7/2013 HIERARCHY of SETTLEMENT HIERARCHY of SETTLEMENT The smallest settlements are greatest in number As the number of settlers (people) and located relatively close to each other. They increase from the single provide residents with basic necessities. dwelling (house ) to hamlet (group The larger settlements (cities) are more complicated, offer variety of goods and services of houses) to village to town to and are located at greater distances from each city, a hierarchy of form and other. -

City of Bassett Iola & Bassett

1000 RD. 1400 RD. 1600 RD. TO GARNETT R 18 E R 19 E 17 16 15 14 13 169 1800 RD. 18 BOYERS NEOSHO LAKE Prairie Spirit Rail-Trail IOLA # 281 & BASSETT # 041 CITY OF OREGON RD. OREGON RD. HOLIDAY LN. IOLA & BASSETT ALLEN COUNTY KANSAS HOLIDAY OSAGE AVE. CT. DODGE DR. T 24 S, T 25 S, R 18 E, R 19 E OKLAHOMA RD. PREPARED BY THE KANSAS AVE. STATE ST. KANSAS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION KENTUCKY ST. BUREAU OF TRANSPORTATION PLANNING PRYOR ST. IN COOPERATION WITH THE 1000 RD. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 21 22 DEWITT MILLER RD. ST. FEDERAL HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION 23 DR. AVE. 24 FUNSTON 19 20 NORTHRUP CANARY SCALE LANE CANARY 0 CARDINAL 1000 2000 CIR. 3000 FEET SEWAGE DR. DISPOSAL 0 200 400 600 800 1000 HIGHLAND METERS CEMETERY PONDS FEBRUARY, 2007 ST. ALLEN COUNTY COMM. JR. COLLEGE POP. 6,081 & 22 PRAIRIEDR POPULATION - U.S. BUREAU OF THE CENSUS 2000 TIMBER WALNUT DR. CERTIFIED TO SECRETARY OF STATE, 7/1/2006 WALNUT RD PROJECTION - LAMBERT CONFORMAL CONIC PATTERSON RD. NORTH DAKOTA RD. BLVD WITH TWO STANDARD PARALLELS WHITE NORTHWESTERN ALAMOSA AT LATITUDE 39o oN AND 38 N BLVD. KDOT makes no warranties, guarantees, or representations for accuracy ST. ALAMOSA CIR. W. ALAMOSA CIR. E. of this information and assumes no liability for errors or omissions. GARFIELD RD. N. JIM ST. MUSTANG CIR. GARFIELD ST. MARSHMALLOW LN. REDBUD LN. EDWARDS ST. W. CIRCLE BUCHANAN ST. BUCHANAN KENWOOD Prairie Spirit Rail-Trail 28 ST. HENRY ST. DEWEY ST. MEADOWBROOK RD. 29 27 MEADOWBROOK RD. -

Seasonal and Spatial Characteristics of Urban Heat Islands (Uhis) in Northern West Siberian Cities

remote sensing Article Seasonal and Spatial Characteristics of Urban Heat Islands (UHIs) in Northern West Siberian Cities Victoria Miles * and Igor Esau Nansen Environmental and Remote Sensing Center/Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, Thormøhlensgt 47, 5006 Bergen, Norway; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +47-97-088-029 Received: 28 July 2017; Accepted: 18 September 2017; Published: 27 September 2017 Abstract: Anthropogenic heat and modified landscapes raise air and surface temperatures in urbanized areas around the globe. This phenomenon is widely known as an urban heat island (UHI). Previous UHI studies, and specifically those based on remote sensing data, have not included cities north of 60◦N. A few in situ studies have indicated that even relatively small cities in high latitudes may exhibit significantly amplified UHIs. The UHI characteristics and factors controlling its intensity in high latitudes remain largely unknown. This study attempts to close this knowledge gap for 28 cities in northern West Siberia (NWS). NWS cities are convenient for urban intercomparison studies as they have relatively similar cold continental climates, and flat, rather homogeneous landscapes. We investigated the UHI in NWS cities using the moderate-resolution imaging spectroradiometer (MODIS) MOD 11A2 land surface temperature (LST) product in 8-day composites. The analysis reveals that all 28 NWS cities exhibit a persistent UHI in summer and winter. The LST analysis found differences in summer and winter regarding the UHI effect, and supports the hypothesis of seasonal differences in the causes of UHI formation. Correlation analysis found the strongest relationships between the UHI and population (log P). -

1999 Design Standards for Central Business District

Design Standards for the Central Business District City of Lubbock, Texas June 1999 Design Standards Credits CREDITS LUBBOCK CITY COUNCIL 1999 LUBBOCK URBAN DESIGN AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION 1999 Windy Sitton, Mayor David Miller, Chair Victor Hernandez Betty Carr, Vice Chair T.J. Patterson Paul Nash David Nelson Marsha Jackson Max Ince Robert Brodkin Marc McDougal Grant Hall Alex K. “Ty” Cooke, Jr. Michael Peters Jim Shearer CITY OF LUBBOCK STAFF FORMER URBAN DESIGN AND HISTORIC P RESERVATION Sally Still Abbe, Planner COMMISSION MEMBERS Jan B. Matthews Gary W. Smith, AIA, Facilities Manager Mary Crites Bill Boon, Planner David Driskill Randy Henson, Senior Planner Garry Kelly Linda Chamales, Supervising Attorney David Murrah Jim Bertram, Director of Strategic Planning CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT AD HOC COMMITTEE CONSULTANT John Berry Dennis Wilson, J.D. Wilson & Associates, Dallas Mackie Bobo Ken Flagg Doris Fletcher Don Kittrell Larry Simmons Abby Quinn JUNE 1999 Page 2 DESIGN STANDARDS FOR THE CBD June 1999 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Background 5 Goal of the Standards 5 Objectives of the Standards 5 Mandated by Zoning Ordinance 6 Improvements Not Required 6 Using the Standards 6 CB-1 West Broadway CB-2 Downtown Site and Building Orientation 7 Site and Building Orientation 13 Building Mass and Scale 7 Building Mass and Scale 13 Proportion and Shape of Elements 8 Proportion and Shape of Elements 14 Building Materials 8 Building Materials 14 Security 9 Security 15 Awnings and Canopies 9 Awnings and Canopies -

Beyond Megalopolis: Exploring Americaâ•Žs New •Œmegapolitanâ•Š Geography

Brookings Mountain West Publications Publications (BMW) 2005 Beyond Megalopolis: Exploring America’s New “Megapolitan” Geography Robert E. Lang Brookings Mountain West, [email protected] Dawn Dhavale Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/brookings_pubs Part of the Urban Studies Commons Repository Citation Lang, R. E., Dhavale, D. (2005). Beyond Megalopolis: Exploring America’s New “Megapolitan” Geography. 1-33. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/brookings_pubs/38 This Report is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Report in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Report has been accepted for inclusion in Brookings Mountain West Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. METROPOLITAN INSTITUTE CENSUS REPORT SERIES Census Report 05:01 (May 2005) Beyond Megalopolis: Exploring America’s New “Megapolitan” Geography Robert E. Lang Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech Dawn Dhavale Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech “... the ten Main Findings and Observations Megapolitans • The Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech identifi es ten US “Megapolitan have a Areas”— clustered networks of metropolitan areas that exceed 10 million population total residents (or will pass that mark by 2040). equal to • Six Megapolitan Areas lie in the eastern half of the United States, while four more are found in the West. -

The New Metropolis: Rethinking Megalopolis

Regional Studies, Vol. 43.6, pp. 789–802, July 2009 The New Metropolis: Rethinking Megalopolis ROBERT LANGÃ and PAUL K. KNOX† ÃVirginia Tech – Metropolitan Institute, 1021 Prince Street, Suite 100, Alexandria, VA 22314, USA. Email: [email protected] †The Metropolitan Institute, School of Public and International Affairs, 123C Burruss Hall (0178), Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA. Email: [email protected] (Received January 2007: in revised form May 2007) LANG R. and KNOX P. K. The new metropolis: rethinking megalopolis, Regional Studies. The paper explores the relationship between metropolitan form, scale, and connectivity. It revisits the idea first offered by geographers Jean Gottmann, James Vance, and Jerome Pickard that urban expansiveness does not tear regions apart but instead leads to new types of linkages. The paper begins with an historical review of the evolving American metropolis and introduces a new spatial model showing changing metropolitan morphology. Next is an analytic synthesis based on geographic theory and empirical findings of what is labelled here the ‘new metropolis’. A key element of the new metropolis is its vast scale, which facilitates the emergence of an even larger trans-metropolitan urban structure – the ‘megapolitan region’. Megapolitan geography is described and includes a typology to show variation between regions. The paper concludes with the suggestion that the fragmented post-modern metropolis may be giving way to a neo-modern extended region where new forms of networks and spatial connectivity reintegrate urban space. Metropolitan morphology New metropolis Spatial connectivity Megapolitan region Spatial model American metropolis LANG R. et KNOX P.K. La nouvelle metropolis: repenser la me´gapole, Regional Studies.