The Validity of Extraterritorial Municipal Zoning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

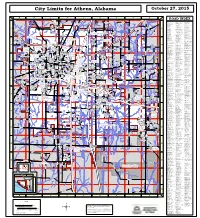

City Limits Map (PDF)

City Limits for Athens, Alabama October 27, 2015 M N O P Q R S T U Ella Grace M Al Hwy 127 Way o Sugar Hill 206 o Rd r ROAD INDEX Ln e Kimzy Carr Rd Sardis Springs s v i ielding l Johnson St F l # FRANK ST, S-15 PALMER ST, N-17 J Berzett Rd e L d o Ruff Cemetery R n R FRAZIER ST, P-15, P-14 PAMELA DR, M-13 r 10TH AV, O-14 d d Wood Ln d a 10TH ST, O-16 FREEMAN AV, P-16, Q-16 PANSY CIR, P-15 n R 12TH ST, O-16, N-16 FRENCH FARMS BLVD, P-16 PARIS LN, P-13 n ris Ln o 14TH ST, N-16 FRENCH WAY, P-16 PARK LN, N-16 Pa t k Muddy Creek l 1ST AV, O-15 FYNE DR, R-15 PARK PL, P-16 E 17 1ST ST, O-15 G PAT INGRAM ST, O-16 127 2ND AV, O-15 GABLES END DR, U-17 PAT ST, N-15 Looney Rd C 2ND ST, O-16 GALE LN, O-15 PATTOCK CT, N-15 Airfield St op I 65 N el A an 3RD AV, O-15 GARDENIA MANOR, U-20 PATTON ST, O-15 HeronDr Holt Rd r d c Rd 3RD ST, O-16 GARRETT DR, P-14 PAULA ST, N-15 13 Runway St t 13 i Airport Rd c 4TH AV, O-15 GARY REDUS DR, P-20 PAVILION CT, R-18 ClemAcre L GEORGE BRALY WAY, Q-20, R- PEACHTREE ST, O-15 n 4TH ST, O-16 Broadwater Pvt Dr Compton Rd E 5TH AV, O-15, N-15 21 PEETE RD, P-23, Q-23 18 260 d Jw Bobo Rd 5TH ST, O-16 GEORGE WASHINGTON ST, P- PEPPER RD, R-16, S-16, U- g 230 th Panther e r o 16, T-16 w r 6TH AV, O-14 20, P-21 w D Branch o t 6TH ST, O-16 GEORGIE EDITH LN, S-15 PHYLLIS ST, S-14 o 258 206. -

City of Bassett Iola & Bassett

1000 RD. 1400 RD. 1600 RD. TO GARNETT R 18 E R 19 E 17 16 15 14 13 169 1800 RD. 18 BOYERS NEOSHO LAKE Prairie Spirit Rail-Trail IOLA # 281 & BASSETT # 041 CITY OF OREGON RD. OREGON RD. HOLIDAY LN. IOLA & BASSETT ALLEN COUNTY KANSAS HOLIDAY OSAGE AVE. CT. DODGE DR. T 24 S, T 25 S, R 18 E, R 19 E OKLAHOMA RD. PREPARED BY THE KANSAS AVE. STATE ST. KANSAS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION KENTUCKY ST. BUREAU OF TRANSPORTATION PLANNING PRYOR ST. IN COOPERATION WITH THE 1000 RD. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 21 22 DEWITT MILLER RD. ST. FEDERAL HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION 23 DR. AVE. 24 FUNSTON 19 20 NORTHRUP CANARY SCALE LANE CANARY 0 CARDINAL 1000 2000 CIR. 3000 FEET SEWAGE DR. DISPOSAL 0 200 400 600 800 1000 HIGHLAND METERS CEMETERY PONDS FEBRUARY, 2007 ST. ALLEN COUNTY COMM. JR. COLLEGE POP. 6,081 & 22 PRAIRIEDR POPULATION - U.S. BUREAU OF THE CENSUS 2000 TIMBER WALNUT DR. CERTIFIED TO SECRETARY OF STATE, 7/1/2006 WALNUT RD PROJECTION - LAMBERT CONFORMAL CONIC PATTERSON RD. NORTH DAKOTA RD. BLVD WITH TWO STANDARD PARALLELS WHITE NORTHWESTERN ALAMOSA AT LATITUDE 39o oN AND 38 N BLVD. KDOT makes no warranties, guarantees, or representations for accuracy ST. ALAMOSA CIR. W. ALAMOSA CIR. E. of this information and assumes no liability for errors or omissions. GARFIELD RD. N. JIM ST. MUSTANG CIR. GARFIELD ST. MARSHMALLOW LN. REDBUD LN. EDWARDS ST. W. CIRCLE BUCHANAN ST. BUCHANAN KENWOOD Prairie Spirit Rail-Trail 28 ST. HENRY ST. DEWEY ST. MEADOWBROOK RD. 29 27 MEADOWBROOK RD. -

Seasonal and Spatial Characteristics of Urban Heat Islands (Uhis) in Northern West Siberian Cities

remote sensing Article Seasonal and Spatial Characteristics of Urban Heat Islands (UHIs) in Northern West Siberian Cities Victoria Miles * and Igor Esau Nansen Environmental and Remote Sensing Center/Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, Thormøhlensgt 47, 5006 Bergen, Norway; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +47-97-088-029 Received: 28 July 2017; Accepted: 18 September 2017; Published: 27 September 2017 Abstract: Anthropogenic heat and modified landscapes raise air and surface temperatures in urbanized areas around the globe. This phenomenon is widely known as an urban heat island (UHI). Previous UHI studies, and specifically those based on remote sensing data, have not included cities north of 60◦N. A few in situ studies have indicated that even relatively small cities in high latitudes may exhibit significantly amplified UHIs. The UHI characteristics and factors controlling its intensity in high latitudes remain largely unknown. This study attempts to close this knowledge gap for 28 cities in northern West Siberia (NWS). NWS cities are convenient for urban intercomparison studies as they have relatively similar cold continental climates, and flat, rather homogeneous landscapes. We investigated the UHI in NWS cities using the moderate-resolution imaging spectroradiometer (MODIS) MOD 11A2 land surface temperature (LST) product in 8-day composites. The analysis reveals that all 28 NWS cities exhibit a persistent UHI in summer and winter. The LST analysis found differences in summer and winter regarding the UHI effect, and supports the hypothesis of seasonal differences in the causes of UHI formation. Correlation analysis found the strongest relationships between the UHI and population (log P). -

1999 Design Standards for Central Business District

Design Standards for the Central Business District City of Lubbock, Texas June 1999 Design Standards Credits CREDITS LUBBOCK CITY COUNCIL 1999 LUBBOCK URBAN DESIGN AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION 1999 Windy Sitton, Mayor David Miller, Chair Victor Hernandez Betty Carr, Vice Chair T.J. Patterson Paul Nash David Nelson Marsha Jackson Max Ince Robert Brodkin Marc McDougal Grant Hall Alex K. “Ty” Cooke, Jr. Michael Peters Jim Shearer CITY OF LUBBOCK STAFF FORMER URBAN DESIGN AND HISTORIC P RESERVATION Sally Still Abbe, Planner COMMISSION MEMBERS Jan B. Matthews Gary W. Smith, AIA, Facilities Manager Mary Crites Bill Boon, Planner David Driskill Randy Henson, Senior Planner Garry Kelly Linda Chamales, Supervising Attorney David Murrah Jim Bertram, Director of Strategic Planning CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT AD HOC COMMITTEE CONSULTANT John Berry Dennis Wilson, J.D. Wilson & Associates, Dallas Mackie Bobo Ken Flagg Doris Fletcher Don Kittrell Larry Simmons Abby Quinn JUNE 1999 Page 2 DESIGN STANDARDS FOR THE CBD June 1999 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Background 5 Goal of the Standards 5 Objectives of the Standards 5 Mandated by Zoning Ordinance 6 Improvements Not Required 6 Using the Standards 6 CB-1 West Broadway CB-2 Downtown Site and Building Orientation 7 Site and Building Orientation 13 Building Mass and Scale 7 Building Mass and Scale 13 Proportion and Shape of Elements 8 Proportion and Shape of Elements 14 Building Materials 8 Building Materials 14 Security 9 Security 15 Awnings and Canopies 9 Awnings and Canopies -

City of Sunnyside

Yakima County Public Services Department Planning Division Yakima County’s 2017 Review of its UGAs and Permitted Densities (as required by the Growth Management Act) Urban Growth Area for City of Sunnyside Staff Report September 14, 2015 Staff contact: Marla Powers, Senior Project Planner [email protected], (509) 574-2924 Introduction The Growth Management Act (GMA) provides: “(a) Each county that designates urban growth areas under RCW 36.70A.110 shall review, according to the schedules established in subsection (5) of this section, its designated urban growth area or areas, and the densities permitted within both the incorporated and unincorporated portions of each urban growth area. In conjunction with this review by the county, each city located within an urban growth area shall review the densities permitted within its boundaries, and the extent to which the urban growth occurring within the county has located within each city and the unincorporated portions of the urban growth areas. “(b) The county comprehensive plan designating urban growth areas, and the densities permitted in the urban growth areas by the comprehensive plans of the county and each city located within the urban growth areas, shall be revised to accommodate the urban growth projected to occur in the county for the succeeding twenty-year period …” [RCW 36.70A.130(3)] Subsection (5) of section RCW 36.70A.130 requires Yakima County and its cities to complete these UGA reviews and revisions by June 30, 2017. [RCW 36.70A.130(5)(c)] This is the Sunnyside analysis of the second of two reports Yakima County will issue as a strategic milestone in meeting the mandate to review and update Yakima County Plan 2015. -

City of Richmond Richmond Etj Map Updated

LN OTHY TIM LGRIM JOURNEY DR R PI D IDGE D H O U S T O N E T JJ R ET R H K R MUS I E N P M M K AL A R L V M S A IC E F T E O OR TT S IA O N G F AR B E DE N R N R S D D RD R O Y O L LD L D D N IX H IE IN S D O R T KL P E U REGENCY CREEK DR S SANDY POINT C S F T ER O O H R J R Y A L C L O E N D N D R E N K L L E O L R N H O U S T O N E T J C H O U S T O N E T J A G D K O E R L U C C E LN R S SPANISH FOREST A A T T G I U D C E R R ST DR A SHADE CRE D G L R UCKE TTS T H O M SHELL LN P Y T 3 O PARR S E O 2 N N 7 A T C P C R H T M O D R C T S F R DR A G O IN E S S S ECAN CRO P 4 F E R D X I E INT Y PO N P SAND 6 N A I LLO PASS G CAVA N L 4 PECAN TRAIL D RAIL A EST T T 1 WC R C L W R RESIDENTIAL : A R I E N F V A I M M E A C Y 3 K C C E 5 F E 9 T A S R G M P TEXAS R any use, building or structure ( or portion of a building or structure ) used for premises that contain habitable rooms for C E P L C A A A T A N A EXTRATERRITORIAL I S N N N L I O 99 R T V L E non-transient occupancy, designed primarily for living, sleeping, cooking, and eating. -

JOHNSON 3 3 R 14 COUNTY 16 E 167TH ST 14 Clare IV RS 1638 RS L INDUSTRIA 16 Ek 16 15 17 14 13 Re R 4 2 22 38°50' 18 1 7 Four AIRPORT C 3 2 3 6 3 14 13 13 56 6 N Em

LEGEND ROADS AND ROADWAY FEATURES Controlled Access (With Interchange) - Interstate CONSERVATION AND RECREATION Kansas Turnpike (KTA) (With Interchange) US Route - Controlled Access (With Interchange) Public Recreation US Route - Divided Scenic, Tourist, or Historical Site US Route - Undivided Trailer Park State Route - Controlled Access (With Interchange) Hotel or Motel State Route - Divided Camp or Lodge (Permanent Site with Building) State Route - Undivided Small Park ( SP - State Park, CP - County Park, RS Route - Divided MP = Municipal Park, SR - Safety Rest Area) RS Route - Paved Fish Hatchery RS Route - Unpaved Game Farm ' 0 Minor Road - Paved Game Preserve or Bird Sanctuary 5 ° 4 Minor Road - Stone or Gravel Rifle Club (Public) 9 Minor Road - Soil Golf Course or Country Club T Side Road or Street in Unincorporated Area Riding Academy, Saddle Club, or Stables 4 O I 30 29 3 - J 5 7 C Race Course or Speedway Ch/Cem. 6 0 T 0 ROAD SYSTEM DESIGNATION 25 14 . KUMP . 2 16 . 2 2 2 W 3 16 5 AVE. T Marina . O S . 4 30 RS T . Rural Secondary System . T O . S S W ' Y S K T . T D 3 T Rodeo Grounds . A O H 3 K V . S 2 0 . OA GRO E RD I 32 H N . E T 0 5 E H E C 2 E E 0 5 2. S C B T 1 1 2 T 2 . 3 s T 4 A 3 D 1 T N J H t P 7 7 3 S 0 8 . C 3 S . t 6 C N 3 F 4 4 8 Y 4 O D V . -

Urban Service Area Plan COMMUNITY FACILITIES

07 Urban Service Area Plan | COMMUNITY FACILITIES COMMUNITY WHAT IS IT? Investment and redevelopment within the existing boundary of the City of Columbia is a priority, but with over 60% of the area population living in unincorporated areas, it is prudent to consider what areas the City can efficiently provide with services beyond its borders. However, any growth presents challenges we should plan 2036 Envision Compass: | Columbia for along with the opportunities that may be presented. The Urban Service Area plan provides a prioritization tool for City Council, staff, and the public to consider about the areas that present the best opportunities for the City’s long-term growth, while minimizing both short-term and long-term challenges. A review of existing infrastructure as well as the reach of our community facilities and services helps define how we classify areas Urban Service Areas (2009 plan) overlaid against City boundaries (February 2019) within the Urban Service Area plan. Areas have been classified as Primary, Secondary, and Long Range areas - or as Donut Holes - in order to represent the general level of priority based on this review. Importantly, this Urban Service Area plan is a policy guide, and not a determination about annexation on any individual property. Annexation of private property in South Carolina is by petition and except in limited circumstances a municipality cannot annex without the participation of the residents or owners of an area being considered for annexation. Whether it is presented with a petition from an owner, a group of freeholders, or a group of electors, City Council is tasked with making the determination of whether or not any proposed annexation is in the best interest of the City. -

Cbd 219-1 Section 219 Cbd Central Business District

CBD SECTION 219 CBD CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT (As amended by Ordinance Nos. O03-10-20, O05-04-06, O09-10-19, O11-02-02, O14-04-05, O15-08-21 and O17-11-20) SECTION 219.1 GENERAL DESCRIPTION The CBD district, with complementary office and related uses, forms the center for commercial, financial, professional, governmental, and cultural activities. These regulations are intended to protect and upgrade the Central Business District for the performance of its primary functions. Pedestrian oriented uses are encouraged. SECTION 219.2 PERMITTED USES AND STRUCTURES 219.2A Retail and other commercial establishments intended to serve the general population of the city. Examples of such establishments include: antiques, appliance, electronics, furniture, general merchandise, office supply and hardware stores, clothing stores, book stores, news stands, jewelers, pet stores, convenience and grocery stores, and restaurants (excluding drive-through) 219.2B Private service establishments intended to serve the general population of the city and requiring a central location. Examples of such establishments include: hotels, banks and similar financial institutions, barber and beauty shops, funeral homes, real estate sales, small appliance repair, shoe repair, income tax service, check advance and title loans, pawnbrokers, and self-service laundries 219.2C General offices; professional offices for doctors, dentists, lawyers, architects, artists, engineers and the like 219.2D Private recreational and amusement establishments including billiards, taverns, -

Population Distribution

Population distribution Ernesto F. L. Amaral April 29–30, 2019 Population and Society (SOCI 312) Outline • Introduction • World population distribution • Residential distribution and urbanization • Economic distribution • Distribution of the US population • Metropolitanization and micropolitanization • Megalopolis • Trends toward deconcentration • Consequences of population distribution 2 Introduction • In some countries, people are more likely to live in rural than urban areas • However, there is an urbanization movement throughout the world – “Without question, the dominant feature of spatial distribution in the United States and other developed countries is the concentration of population in densely settled urban areas” (Fossett 2005) • This chapter examines – How the inhabitants of the world are distributed – How most of us have become city dwellers rather than cave dwellers, as was the case thousands of years ago 3 World population distribution • About 1/3 of the earth’s land is permanently inhabited – Areas such as the Arctic, the Antarctic, vast deserts (e.g., the Sahara) have very few people – Areas with rugged mountains make it almost impossible for humans to survive • Most populated regions of the world – South Asia (mainly India) – East Asia (mainly China) • Oceania (primarily Australia) is the least 5 World 7,238 Estimated midyear Africa 1,136 Northern Africa 217 population by major Western Africa 339 Eastern Africa 378 areas and regions, Middle Africa 142 Southern Africa 61 2014 (in millions) Americas 972 Northern America 353 Central America 165 Caribbean 43 South America 410 Asia 4,351 Western Asia 255 Central Asia 67 South Asia 1,806 Southeast Asia 621 East Asia 1,601 Europe 741 Western Europe 190 Northern Europe 102 Eastern Europe 294 Southern Europe 154 Oceania 39 Source: Population Reference Bureau, 2014. -

Population of Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas: 1960 and 1950

1960 SUPPL:EM.ENTAR Y Census of R~PD;RIS Population April 10, 1961 PC( Sl) -1 POPULATION OF STANDARD METROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREAS: 1960 AND 1950 (The data shown here are being issued in advance of their publication in Final Report PC(l)-lA, which is scheduled to be published in May 1961 and which will contain additional sumnary information on the numbers and geographic distribution of the population. The discussion in the text of the present report refers to the 212 SMSA•s in the 50 States and the District of Columbia; however, statistics for the three SMSA's in Puerto Rico are given in table 3, This report supersedes Pre liminary Report PC(P3)-4) Approximately 84 percent of the increase from 36~9 million persons.to 54,9 million. The in the total population of the United States nonmetropolitan territory increased from 62.0 between 1950 and 1960 occurred in standard million persons to 66.4 million, an increase metropolitan statistical areas (SMSA 1 s), that of about 7 percent. is, in cities of 50,000 or more and the out lying areas surrounding them. The 212 SMSA's This general pattern of metropolitan increased by 23.6 million persons, and of this nonmetropoli tan growth represents a continu increase 17. 9 million occurr'ed in the outlying ation of a similar pattern which occurred in parts of the SMSA 1 s and 5,6 million in the the decade 1940 to 1950. In that decade, central cities. Thus the population increase nearly 80 percent of the population growth of in the outlying parts of the SMSA 1 s accounted the country occurred in standard metropolitan for nearly two-thirds of the total population statistical areas. -

Amended and Restated Redevelopment Plan for the Merged Central Business District and West End Redevelopment Project

AMENDED AND RESTATED REDEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR THE MERGED CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT AND WEST END REDEVELOPMENT PROJECT Prepared by the REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY OF THE CITY OF AZUSA AZUSA, CALIFORNIA TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. [Section 100] INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................ 1 A. [Section 101] General.............................................................................................................. 1 B. [Section 102] Goals and Objectives ........................................................................................ 2 C. [Section 103] Merged Project .................................................................................................. 3 II. [Section 200] MERGED PROJECT AREA BOUNDARY AND LEGAL DESCRIPTION .................................................................................................. 3 III. [Section 300] REDEVELOPMENT ACTIVITIES................................................................................... 3 A. [Section 301] General.............................................................................................................. 3 B. [Section 302] Owner Participation and Business Reentry Preferences................................... 4 1. [Section 303] Owner Participation .............................................................................. 4 2. [Section 304] Business Reentry Preferences ............................................................. 5 3. [Section 305] Participation Agreements