BUILDING from SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg After Apartheid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gauteng Provincial Gazette Vol 19 No 110 Dated 24 April 2013

T E U N A G THE PROVINCE OF G DIE PROVINSIE UNITY DIVERSITY GAUTENG P IN GAUTENG R T O N V E IN M C RN IAL GOVE Provincial Gazette Extraordinary Buitengewone Provinsiale Koerant Vol. 19 PRETORIA, 24 APRIL 2013 No. 110 We oil hawm he power to preftvent kllDc AIDS HEIRINE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 301707—A 110—1 2 No. 110 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY, 24 APRIL 2013 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS • INHOUD Page Gazette No. No. No. GENERAL NOTICE 1021 Gauteng Gambling Act, 1995: Application for a gaming machine licence..................................................................... 3 110 BUITENGEWONE PROVINSIALE KOERANT, 24 APRIL 2013 No. 110 3 GENERAL NOTICE NOTICE 1021 OF 2013 Gauteng Gambling and Betting Act 1995 Application for a Gaming Machine Licence Notice is hereby given that: 1. -

Significant Changes in Dividend Policy and Insider Trading Activity on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange

S.AfrJ.Bus.Mgmt.1991,22(4) 75 Significant changes in dividend policy and insider trading activity on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange Narendra Shana Graduate School of Business, University of Durban-Westville, Private Bag X54001, Durban 4000, Republic of South Africa Received 29 July 1991; accepted 30 September 1991 The objectiv~ with this article was to dete~ine whether insider trading related to unannounced dividend policy chan~es. provided abnormal returns fo~ ~hares listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE). 1ne results indicate wthat insidersd te ted as da group· th seem· to exhibitth . 'remarkable. timing ability' · Significant chan ges m· ms1· 'der tradi ng act1v1ty· · er~ e ~ u~~g e s1x-mon penod pnor to the resumption (omission) announcement. Company insiders tradm_g pnor to dividend chw:iges announcements earned consistently large positive abnormal returns (avoid large negative a~no~al returns) .• It 1s recom~ended that company insiders be required to make public the market positions they t~e m therr ~mpany s sh~es. ThlS can be expected to reduce the abnormal returns derived from insider tradin and will also contnbute towards improving the efficiency of the JSE. g Die doel m«:1 hi~die. ~el was_ om te ~paal of binnelcring-handelstransaksies, wat betrelcking het op onaangelcondig de verandermge m div1den~le1d,. ge!e1 het tot abnormale opbrengste vir aandele wat op die Johannesburgse Effekte beurs (JE) g_enoteer word. Die bev1ndmgs het d~op gedui dat lede van die binnelcring, as 'n groep, 'n merlcwaardige tydsberek~nmgsvermoi! geopenbaar het: Beteken~v~lle veranderinge in biMekring-handelstransaksies is ontdelc ge d_urende die ses m~de tydperk wat ~1e a~kond1gmg van hervatting (weglating) voorafgegaan het. -

Company Profile 2019/20

Company Profile 2019/20 Fourways Airconditioning: a story of continuous growth and expansion From selling home airconditioning units from a small outlet in 1999, Fourways Airconditioning has grown to become a national – and international – operation, offering a wide range of aircons as well as Domestic and Commercial Heat Pumps plus home appliances. Fourways Airconditioning began as a small company in Kya-Sands selling Samsung airconditioners to COD customers in 1999. Since those early days, Fourways Johannesburg has expanded twice to new premises, while our Pretoria branch, established in 2009 to serve local customers, has also moved premises to accommodate ever-increasing volumes. Appointed as authorised importers and distributors of Samsung airconditioners in South Africa in 2004, Fourways supplies everything from small domestic split units to large Samsung DVM units. In 2006, Fourways also launched its own range of Alliance airconditioners and Heat Pumps. OUR VISION OUR MISSION To become the No. 1 Supplier of To provide our dealers – and customers – with Airconditioning and Heat Pumps units, the best-quality units, backed up by the best spares and service in South Africa. service and marketed by top-class people in a responsible and strategic manner. Our Samsung range of products Fourways Airconditioning stocks and sells a wide range of Samsung airconditioners from small midwall splits up to large DVM S units and Chillers offering world-class energy efficiency. Our Samsung product range includes split airconditioners, cassette units, ducted units, Free Joint Multis, underceilings and floor standing airconditioners (all available in inverter and non-inverter form). Samsung’s large DVM S is an innovative system utilizing new 3rd generation Samsung Scroll Compressor technology. -

MWS Confirmation Package Distribution

20 OCTOBER - 26 OCTOBER 2013 TOURNAMENT CONFIRMATION PACKAGE www.worldindoorcricketfederation.com 01 Dear World Indoor Cricket Federation participants I would like to extend a warm South African welcome to all players, managers and officials taking part in the Indoor Cricket Masters World Series 2013. The tournament will take place in the Gauteng province which can be considered as the sporting hub of the African continent. South Africa has played host to a few major sporting world cups in the past, the largest three being the Soccer, Cricket and Rugby world cups, so we have developed a reputation for hosting fantastic international Indoor Cricket events. Gauteng Province is situated a stone throw away from some of the most spectacular tourist destinations we have, so visiting some of these before or after the tournament would be an experience not to be missed. There are a host of game reserves within a 3 hour drive where you could get a true experience of the famous African Bushveld. There you would be able to see the “big 5” which are the Lion, Elephant, Rhino, Leopard and Buffalo, in their natural environment. We will also be situated two hours away from Sun City, South Africa’s version of Las Vegas. Sun City is best known for playing host to the $2 mill golf tournament, five star hotels and casino’s all nestled into the Pilandsberg game reserve where you will also find the “Big 5”. Indoor Cricket or “Action Cricket” as it is better known in South Africa is one of the fastest growing sports in this sport mad country. -

Directions from M1 South to MICM Mtembu Street, Central Western

Directions from M1 South to MICM Mtembu Street, Central Western Jabavu, Soweto, 1809. We are behind the Morris Isaacson Secondary School. Copy and paste this link to Google Maps: https://goo.gl/maps/msUZX1WKjTL2 Alternatively get directions on Google maps www.maps.google.co.za A: M1 South, Randburg, Gauteng, South Africa B: Mtembu Street, Jabavu, Soweto, Gauteng, South Africa Coordinates: S 26.24701 ̊ E 27.87261 ̊ From M1 SOUTH De Villiers Graaf Motorway (Bloemfontein) • Pass Jan Smuts and Empire Exits • Cross elevated section through Newtown • BEAR RIGHT at end of elevated section: M1 SOWETO/BLOEMFONTEIN • Then IMMEDIATELY BEAR LEFT ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Take EXIT 10C for M1 BLOEMONTEIN • Pass Gold Reef City on your right • Pass M17 exit for Xavier Street & Apartheid Museum • Bear RIGHT following M1 BLOEMFONTEIN ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Take EXIT 391 M68 SOWETO/N12 KIMBERLEY/N1 BLOEMFONTEIN • Bear left and pass under Aerodrome Road ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Take EXIT M68 SOWETO/MONDEOR ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ At T-Junction TURN RIGHT on M68 SOWETO (Old Potchefstroom Road) • Continue straight for 7.5km • Pass Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital on your left • Becomes Chris Hani Road • Pass Orlando Towers (cooling towers) and lake on your right • Pass University of Johannesburg -

Sports Report 2019

Greenside High School Sports highlights and achievements 2019. Greenside High School believes strongly in the Nelson Mandela quote that says: “Sport has the power to change the world; it has the power to inspire. It has the power to unite people in a way that little else does. It speaks to the youth in a language they understand. Sport can create hope, where there was once only despair. It is more powerful than governments in breaking down racial barriers. It laughs in the faces of all types of discrimination. Sport is a game of lovers.” We are truly grateful as a school that our learners are exposed to 13 sporting codes and many see themselves having career opportunities in the respective sporting codes that we offer at our school. Even though we were faced with a few challenges in the year, we have also developed and our perspectives and goals have broadened. We would like to celebrate the achievements of our learners this far in all respective codes. SPORTS HIGHLIGHTS AND ACHIEVEMNTS 2019 | s Rugby The focus in every year is to introduce the girls to appropriate technique and develop a safe and competitive environment. They had a very successful league competing with 12 schools and the U16 girls being undefeated in 2019 and our U18 only losing 1 friendly game. Almost all the girls both u16 and u18s were invited to the National Rugby Week trials. Two senior girls unfortunately did not make it in the last trials and three players were chosen for the u18 National Week Team. -

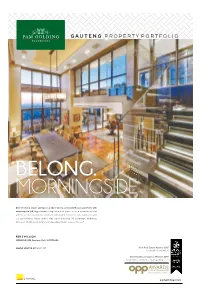

Gauteng Property Portfolio

GAUTENG PROPERTY PORTFOLIO BELONG. MORNINGSIDE One-of-a-kind, secure and spacious triple-storey, corner penthouse apartment, with uninterrupted 270-degree views. Refrigerated walk-in wine room, 4 palatial bedrooms with the wooden floor theme continued, with marble covered en suite bathrooms and a state-of-the-art home cinema with top-of-the-range AV equipment. Numerous balconies, all with views, with a heated pool and steam-room on the roof. R39.5 MILLION MORNINGSIDE, Gauteng Ref# HP1139604 WAYNE VENTER 073 254 1453 Best Real Estate Agency 2015 South Africa and Africa Best Real Estate Agency Website 2015 South Africa and Africa / pamgolding.co.za pamgolding.co.za EXERCISE YOUR FREEDOM 40KM HORSE RIDING TRAILS Our ultra-progressive Equestrian Centre, together with over 40 kilometres of bridle paths, is a dream world. Whether mastering an intricate dressage movement, fine-tuning your jump approach, or enjoying an exhilarating outride canter, it is all about moments in the saddle. The accomplished South African show jumper, Johan Lotter, will be heading up this specialised unit. A standout health feature of our Equestrian Centre is an automated horse exerciser. Other premium facilities include a lunging ring, jumping shed, warm-up arena and a main arena for show jumping and dressage events. The total infrastructure includes 36 stables, feed and wash areas, tack- rooms, office, medical rooms and groom accommodation. Kids & Teens Wonderland · Sport & Recreation · Legendary Golf · Equestrian · Restaurants & Retail · Leisure · Innovative Infrastructure -

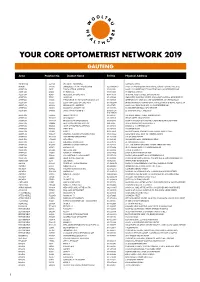

Your Core Optometrist Network 2019 Gauteng

YOUR CORE OPTOMETRIST NETWORK 2019 GAUTENG Area Practice No. Doctor Name Tel No. Physical Address ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE AKASIA 478490 ENGELBRECHT A J A - WONDERPARK 012 5490086/7 SHOP 404 WONDERPARK SHOPPING C, CNR OF HEINRICH AVE & OL ALBERTON 58017 TORGA OPTICAL ALBERTON 011 8691918 SHOP U 142, ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING MALL, VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 141453 DU PLESSIS L C 011 8692488 99 MICHELLE AVENUE ALBERTON 145831 MEYERSDAL OPTOMETRISTS 011 8676158 10 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 177962 JANSEN N 011 9074385 LEMON TREE SHOPPING CENTRE, CNR SWART KOPPIES & HEIDELBERG RD ALBERTON 192406 THEOLOGO R, DU TOIT M & PRINSLOO C M J 011 9076515 ALBERTON CITY, SHOP S03, CNR VOORTREKKER & DU PLESSIS ROAD ALBERTON 195502 ZELDA VAN COLLER OPTOMETRISTS 011 9002044 BRACKEN GARDEN SHOPPING CNTR, CNR DELPHINIUM & HENNIE ALBERTS STR ALBERTON 266639 SIKOSANA J T - ALBERTON 011 9071870 SHOP 23-24 VILLAGE SQUARE, 46 VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 280828 RAMOVHA & DOWLEY INC 011 9070956 53 VOORTREKKER ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 348066 JANSE VAN RENSBURG C Y 011 8690754/ 25 PADSTOW STREET, RACEVIEW 072 7986170 ALBERTON 650366 MR IZAT SCHOLTZ 011 9001791 172 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN P 011 9078745 1E FORE STREET, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7009259 BRACKEN CITY OPTOMETRISTS 011 8673920 SHOP 26 BRACKEN CITY, HENNIE ALBERTS ROAD, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7010834 NEW VISION OPTOMETRISTS CC 090 79235 19 NEW QUAY ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7010893 I CARE OPTOMETRISTS ALBERTON 011 9071046 SHOPS -

Beyond Megalopolis: Exploring Americaâ•Žs New •Œmegapolitanâ•Š Geography

Brookings Mountain West Publications Publications (BMW) 2005 Beyond Megalopolis: Exploring America’s New “Megapolitan” Geography Robert E. Lang Brookings Mountain West, [email protected] Dawn Dhavale Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/brookings_pubs Part of the Urban Studies Commons Repository Citation Lang, R. E., Dhavale, D. (2005). Beyond Megalopolis: Exploring America’s New “Megapolitan” Geography. 1-33. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/brookings_pubs/38 This Report is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Report in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Report has been accepted for inclusion in Brookings Mountain West Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. METROPOLITAN INSTITUTE CENSUS REPORT SERIES Census Report 05:01 (May 2005) Beyond Megalopolis: Exploring America’s New “Megapolitan” Geography Robert E. Lang Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech Dawn Dhavale Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech “... the ten Main Findings and Observations Megapolitans • The Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech identifi es ten US “Megapolitan have a Areas”— clustered networks of metropolitan areas that exceed 10 million population total residents (or will pass that mark by 2040). equal to • Six Megapolitan Areas lie in the eastern half of the United States, while four more are found in the West. -

Government Gazette Republic of Namibia

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA N$2.55 WINDHOEK - 7 May 1999 No. 2101 0 CONTENTS Page TRADE MARKS ..................................................................................................................... 1 APPLICATIONS FOR REGISTRATION OF TRADE MARKS IN NAMIBIA (Applications accepted in terms of Act No. 48 of 1973) Any person who has grounds for objection to any of the following trade marks, may, within the prescribed time, lodge Notice of Opposition on form SM6 contained in the Second Schedule to the Trade Marks Rules in Namibia, 1973. The prescribed time is two months after the date of advertisement. This period may on application be extended by the Registrar. Where the Gazette is issued late, the period of opposition will count as from the date of issue and a notice relating thereto will be displayed on the public notice board in the Trade Marks Registry. Formal opposition should not be lodged until after notice has been given by letter to the applicant for registration so as to afford him an opportunity of withdrawing his application before the expense of preparing the Notice of Opposition is incurred. Failing such notice to the applicant an opponent may not succeed in obtaining an order for costs. "B" preceding the number indicates Part B of the Trade Mark Register. Neither the office mentioned hereunder nor Solitaire Press CC, acting on behalf of the Government of Namibia, guarantee the accuracy of this publication or undertake any responsibility for errors or omissions or their consequences. E.T. KAMBOUA -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Redefining Global Cities the Seven Types of Global Metro Economies

REDEFINING GLOBAL CITIES THE SEVEN TYPES OF GLOBAL METRO ECONOMIES REDEFINING GLOBAL CITIES THE SEVEN TYPES OF GLOBAL METRO ECONOMIES GLOBAL CITIES INITIATIVE A JOINT PROJECT OF BROOKINGS AND JPMORGAN CHASE JESUS LEAL TRUJILLO AND JOSEPH PARILLA THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION | METROPOLITAN POLICY PROGRAM | 2016 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ith more than half the world’s population now living in urban areas, cities are the critical drivers of global economic growth and prosperity. The world’s 123 largest metro areas contain a little Wmore than one-eighth of global population, but generate nearly one-third of global economic output. As societies and economies around the world have urbanized, they have upended the classic notion of a global city. No longer is the global economy driven by a select few major financial centers like New York, London, and Tokyo. Today, members of a vast and complex network of cities participate in international flows of goods, services, people, capital, and ideas, and thus make distinctive contributions to global growth and opportunity. And as the global economy continues to suffer from what the IMF terms “too slow growth for too long,” efforts to understand and enhance cities’ contributions to growth and prosperity become even more important. In view of these trends and challenges, this report redefines global cities. It introduces a new typology that builds from a first-of-its-kind database of dozens of indicators, standardized across the world’s 123 largest metro economies, to examine global city economic characteristics, industrial structure, and key competitive- ness factors: tradable clusters, innovation, talent, and infrastructure connectivity. The typology reveals that, indeed, there is no one way to be a global city.