JOHANNESBURG a Challenge to Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gauteng Provincial Gazette Vol 19 No 110 Dated 24 April 2013

T E U N A G THE PROVINCE OF G DIE PROVINSIE UNITY DIVERSITY GAUTENG P IN GAUTENG R T O N V E IN M C RN IAL GOVE Provincial Gazette Extraordinary Buitengewone Provinsiale Koerant Vol. 19 PRETORIA, 24 APRIL 2013 No. 110 We oil hawm he power to preftvent kllDc AIDS HEIRINE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 301707—A 110—1 2 No. 110 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY, 24 APRIL 2013 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS • INHOUD Page Gazette No. No. No. GENERAL NOTICE 1021 Gauteng Gambling Act, 1995: Application for a gaming machine licence..................................................................... 3 110 BUITENGEWONE PROVINSIALE KOERANT, 24 APRIL 2013 No. 110 3 GENERAL NOTICE NOTICE 1021 OF 2013 Gauteng Gambling and Betting Act 1995 Application for a Gaming Machine Licence Notice is hereby given that: 1. -

BUILDING from SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg After Apartheid

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH 471 DOI:10.1111/1468-2427.12180 — BUILDING FROM SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg after Apartheid claire w. herbert and martin j. murray Abstract By the start of the twenty-first century, the once dominant historical downtown core of Johannesburg had lost its privileged status as the center of business and commercial activities, the metropolitan landscape having been restructured into an assemblage of sprawling, rival edge cities. Real estate developers have recently unveiled ambitious plans to build two completely new cities from scratch: Waterfall City and Lanseria Airport City ( formerly called Cradle City) are master-planned, holistically designed ‘satellite cities’ built on vacant land. While incorporating features found in earlier city-building efforts, these two new self-contained, privately-managed cities operate outside the administrative reach of public authority and thus exemplify the global trend toward privatized urbanism. Waterfall City, located on land that has been owned by the same extended family for nearly 100 years, is spearheaded by a single corporate entity. Lanseria Airport City/Cradle City is a planned ‘aerotropolis’ surrounding the existing Lanseria airport at the northwest corner of the Johannesburg metropole. These two new private cities differ from earlier large-scale urban projects because everything from basic infrastructure (including utilities, sewerage, and the installation and maintenance of roadways), -

Infrastructures of Property and Debt: Making Affordable Housing, Race and Place in Johannesburg

Infrastructures of Property and Debt: making affordable housing, race and place in Johannesburg A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Siân Butcher IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advisors: Helga Leitner and Eric Sheppard Department: Geography, Environment and Society July 2016 ©2016 by Siân Butcher Acknowledgements This dissertation is not only about debt, but has been made possible through many debts, but also gifts of various kinds. I want to start by thanking the following for their material support of my graduate study at the University of Minnesota (UMN), my dissertation research and my writing time. Institutionally, my homes have been the department of Geography, Environment and Society (GES) and the Interdisciplinary Center for the Study of Global Change (ICGC). ICGC supported me for two years in partnership with the Center for Humanities Research (CHR) at the University of the Western Cape (UWC) through the generous ICGC-Mellon Scholar fellowship. Pre-dissertation fieldwork between 2010-2011 was supported by GES, ICGC, the York-Wits Global Suburbanisms project, and the Social Science Research Council’s Dissertation Proposal Development Fellowship (SSRC DPDF). Dissertation fieldwork in Johannesburg was made possible by UMN’s Global Spotlight Doctoral Dissertation International Research Grant (2012- 2013) and the immeasurable support of friends and family. My two years of writing was enabled by a semester’s residency at the CHR at UWC in Cape Town; a Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship from the University of Minnesota (2014-5), and a home provided by my partner Trey Smith and then my mother, Sue Butcher. -

Download Yeoville Then And

YEOVILLE STUDIO_housing// arpl 2000 wits school of architecture & planning 2 3 YEOVILLE STUDIO_housing// arpl 2000 wits school of architecture & planning YEOVILLE THEN AND NOW INTRODUCTION BASED IN YEOVILLE, THE GROUP SET OUT IN DOCUMENTING THE PERSONAL HISTORIES OF THE PEOPLE AND THE PLACES THEY’VE LIVED. THEIR JOURNEYS WERE MAPPED INTO AND WITHIN YEO- URBAN (HIS)STORIES VILLE. AFTER THOUROUGH RESEARCH A BRIEF HISTORY OF YEO- VILLE IN THE CONTEXT OF JOHANNESBURG IS PROVIDED. DATA INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY SUCH AS PHOTOGRAPHS, AERIAL MAPS, TIMELINES,PORTRAITS YEOVILLE THEN AND NOW AND WRITTEN TRANSCRIP OF INTERVIEWS OF THE JOURNEY ARE DEMONSTRED. METHODOLOEGY A CLEAR AND PRECISE METHOD OF NETWORKING FLOWS THROUGH THE PROJECT SHOWING A DEFINED MOVEMENT OF THE JOURNEY AND THE RELATIONSHIPS WITHIN YEOVILLE. BY MEANS OF GROUP INTERVIEWS WE WERE ABLE TO SET A COM- FORT LEVEL GAINING MORE CONFIDENCE IN THE INTERVIEWEES AND THEREFORE WERE ABLE TO COLLECT MORE VAST AND DEEP INFORMATION. WE FOUND THIS METHOD EXTREMELY SUCCESFUL AS ONE PERSON BEGAN TO LEAD US TO THE NEXT CREATING A JOURNEY PATH AS WELL AS AN INTERESTING LINE OF INTERAC- TIONS. THERE WAS ALSO AN EMPHASIS PLACED ON BUILDINGS AND THERIR SOCIALAND HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE. arpl 2000 wits school of architecture & planning arpl 2000 wits school of architecture & planning YEOVILLE STUDIO_housing// YEOVILLE STUDIO_housing// 4 5 YEOVILLE NETWORKING In order to understand and analyse a space and the people that move through it one needs to recognize the history and culture of the place in cohesion with the physical and personal now. We must understand the links and connections that form part of the human matrix; how do we communicate, how do we survive amongst each other? These answers coincide within the network that each individu- al shares with another, whether it is a geographical or personal link. -

37908 15-8 Roadcarrierp

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA August Vol. 590 Pretoria, 15 2014 Augustus No. 37908 PART 1 OF 2 N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 403005—A 37908—1 2 No. 37908 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 15 AUGUST 2014 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS INHOUD Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. Transport, Department of Vervoer, Departement van Cross Border Road Transport Agency: Oorgrenspadvervoeragentskap aansoek- Applications for permits:.......................... permitte: .................................................. Menlyn..................................................... 3 37908 Menlyn..................................................... 3 37908 Applications concerning Operating Aansoeke -

The City of Johannesburg Is One of South Africa's Seven Metropolitan Municipalities

NUMBER 26 / 2010 Urbanising Africa: The city centre revisited Experiences with inner-city revitalisation from Johannesburg (South Africa), Mbabane (Swaziland), Lusaka (Zambia), Harare and Bulawayo (Zimbabwe) By: Editors Authors: Alonso Ayala Peter Ahmad Ellen Geurts Innocent Chirisa Linda Magwaro-Ndiweni Mazuba Webb Muchindu William N. Ndlela Mphangela Nkonge Daniella Sachs IHS WP 026 Ahmad, Ayala, Chirisa, Geurts, Magwaro, Muchindu, Ndlela, Nkonge, Sachs Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited 1 Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited Experiences with inner-city revitalisation from Johannesburg (South Africa), Mbabane (Swaziland), Lusaka (Zambia), Harare and Bulawayo (Zimbabwe) Authors: Peter Ahmad Innocent Chirisa Linda Magwaro-Ndiweni Mazuba Webb Muchindu William N. Ndlela Mphangela Nkonge Daniella Sachs Editors: Alonso Ayala Ellen Geurts IHS WP 026 Ahmad, Ayala, Chirisa, Geurts, Magwaro, Muchindu, Ndlela, Nkonge, Sachs Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited 2 Introduction This working paper contains a selection of 7 articles written by participants in a Refresher Course organised by IHS in August 2010 in Johannesburg, South Africa. The title of the course was Urbanising Africa: the city centre revisited - Ensuring liveable and sustainable inner-cities in Southern African countries: making it work for the poor. The course dealt in particular with inner-city revitalisation in Southern African countries, namely South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Inner-city revitalisation processes differ widely between the various cities and countries; e.g. in Lusaka and Mbabane few efforts have been undertaken, whereas Johannesburg in particular but also other South Africa cities have made major investments to revitalise their inner-cities. The definition of the inner-city also differs between countries; in Lusaka the CBD is synonymous with the inner-city, whereas in Johannesburg the inner-city is considered much larger than only the CBD. -

THE ORDER of APPEARANCES Urban Renewal in Johannesburg Mpho Matsipa

THE ORDER OF APPEARANCES Urban Renewal in Johannesburg By Mpho Matsipa A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Nezar Alsayyad, Chair Professor Greig Crysler Professor Ananya Roy Spring 2014 THE ORDER OF APPEARANCES Urban Renewal in Johannesburg Mpho Matsipa TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract i Acknowledgements ii List of Illustrations iii List of Abbreviations vi EAVESDROPPING 1 0.1 Regimes of Representation 6 0.2 Theorizing Globalization in Johannesburg 9 0.2.1 Neo‐liberal Urbanisms 10 0.2.2 Aesthetics and Subject Formation 12 0.2.3 Race Gender and Representation 13 0.3 A note on Methodology 14 0.4 Organization of the Text 15 1 EXCAVATING AT THE MARGINS 17 1.1 Barbaric Lands 18 1.1.1 Segregation: 1910 – 1948 23 1.1.2 Grand Apartheid: 1948 – 1960s 26 1.1.3 Late Apartheid: 1973 – 1990s 28 1.1.4 Post ‐ Apartheid: 1994 – 2010 30 1.2 Locating Black Women in Johannesburg 31 1.2.1 Excavations 36 2 THE LANDSCAPE OF PUBLIC ART IN JOHANNESBURG 39 2.1 Unmapping the City 43 2.1.1 The Dying Days of Apartheid: 1970‐ 1994 43 2.1.2 The Fiscal Abyss 45 2.2 Pioneers of the Cultural Arc 49 2.2.1 City Visions 49 2.2.2 Birth of the World Class African City 54 2.2.3 The Johannesburg Development Agency 58 2.3 Radical Fragments 61 2.3.1 The Johannesburg Art in Public Places Policy 63 3 THE CITY AS A WORK OF ART 69 3.1 Long Live the Dead Queen 72 3.1.2 Dereliction Can be Beautiful 75 3.1.2 Johannesburg Art City 79 3.2 Frontiers 84 3.2.1 The Central Johannesburg Partnership 19992 – 2010 85 3.2.2 City Improvement Districts and the Urban Enclave 87 3.3 Enframing the City 92 3.3.1 Black Woman as Trope 94 3.3.2 Branding, Art and Real Estate Values 98 4 DISPLACEMENT 102 4.1 Woza Sweet‐heart 104 4.1.1. -

Spatial Distribution and Source Identification of Mercury in Dust Affected by Gold Mining in Johannesburg, South Africa

Proceedings of the International Conference of Recent Trends in Environmental Science and Engineering (RTESE'17) Toronto, Canada – August 23 – 25, 2017 Paper No. 104 DOI: 10.11159/rtese17.104 Spatial Distribution and Source Identification of Mercury in Dust Affected by Gold Mining in Johannesburg, South Africa Ewa M. Cukrowska, Bongani N. Yalala, Hlanganani Tutu, Luke Chimuka Molecular Sciences Institute, School of Chemistry, University of the Witwatersrand P. Bag X3, WITS 2050, Johannesburg, South Africa [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract - Mercury concentrations (HgTOT) were analysed in total and size fractions in urban dust. The results showed that HgTOT -1 ranged from 270 to 1350 µg kg for PM25 particle size fraction. The distribution was as follows: HgIndustrial > HgCBD > HgResidential. The HgTOT showed a positive correlation with percent volume of the PM25 size fraction. This indicated that as the particles size decreased, the HgTOT increased. The dust was mainly characterized by high concentration levels of quartz (74.3 to 97.6 wt. %). The tailings dumps showed similar levels of quartz (65 to 81 wt. %), which indicated that tailings are the major anthropogenic sources of mercury in the dust. Both, the tailings dumps and the dust samples showed well defined crystalline structures of the quartz coated with trace elements. Keywords: Mercury, Particulate Matter, Dust, Tailings dumps 1. Introduction Gold mining in the Witwatersrand basin commenced in 1886, and the initial method of extraction was the mercury amalgamation. This process led to the generation of sand dumps, which are characterized by large particle sizes, are often domed shaped, and still contain small amount of gold (0.6 g t-1) [1]. -

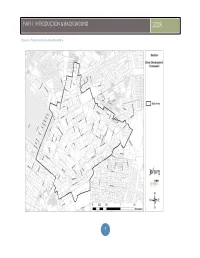

Part 1: Introduction & Background

PART 1: INTRODUCTION & BACKGROUND 2008 Figure 3: Proposed Study Area Boundary 3 PART 1: INTRODUCTION & BACKGROUND 2008 3. Sandton Context The Sandton of today is the result of an extensive journey of transformation, collaboration and the pursuit of a specific vision during the past 30 years. According to the Sandton Management District (2007) Sandton is without a doubt one of the most important business and financial districts in South Africa, as well as sub-Saharan Africa. Looking back over the past three decades, the rich heritage of the Sandton and Sandton Central of today is clear. The history of Sandton as described by the Sandton Central Management District (2007) can be summarised as follows: 10 000 years ago the plains of Sandton were traversed by stone-age hunters 1000 years ago tribesmen watered their herds at Sandton's many streams and springs 400 years ago the tribesmen ran an iron-smelting economy 120 years ago the richest gold field on earth was discovered 100 years ago Sandton comprised Johannesburg's lush market garden 50 years ago Sandton comprised a world of rich estates and sandy horse trails. Sandtonions were dubbed the 'mink and manure set' Figure 4: The Sandton Skyline 30 years ago the country's premier shopping mall, Sandton City, was built. The 'Southern Suburbs' of Sandton were laid out quite early in the century and by the thirties, they were well established as 'gentleman estate' areas with the majority of the properties being one morgen or larger in size. At this stage they formed the 'northern' suburbs of Johannesburg and in some cases, extended beyond the boundaries of the city. -

Water and Development in the Context of the Greater

Gold, Scorched Earth and Water: The Hydropolitics of Development in Johannesburg Paper presented to the Seminar on Water Management in Megacities at the Stockholm Water Symposium on 15 August 2004 By Anthony Turton Gibb-SERA Chair in IWRM & Universities Partnership for Transboundary Waters [email protected] With various inputs from Craig Schultz, Hannes Buckle, Mapule Kgomongoe, Tinyiko Maluleke & Mikael Drackner CSIR Report No: ENV-P-CONF 2004-022 Abstract Johannesburg is one of the few major cities of the world that does not lie on a river, a lake or a seafront. Since the discovery of gold in 1886, Johannesburg has grown from a dusty mining town to a major urban and industrial conurbation that houses and sustains a quarter of the total population of South Africa, accounting for 10% of the economic activity on the entire African continent. Water supply to Johannesburg is done by Rand Water, which is credited with sustaining the largest human concentration in the southern hemisphere that is not located on a river. This poses major challenges to engineers because the geology of the gold-bearing reef is also associated with the watershed between two major international river basins in Southern Africa – the Orange and the Limpopo. Being classified as Pivotal Basins1 in the Southern African Hydropolitical Complex, these two river basins form the strategic backbone to the economies of the four most economically developed countries in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region - South Africa, Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe. In order to sustain the urban and industrial complex in the Greater Johannesburg Conurbation, massive Inter-Basin Transfers (IBTs) are necessary, posing a challenge to the notion of a river basin as a fundamental unit of management within the framework of Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM), because in essence every river basin in South Africa is now hydraulically connected to every other river basin, with this pattern starting to cross international borders in an increasingly complex web of transfer schemes. -

Our Areas of Finance Our Branches

OUR BRANCHES OUR AREAS OF FINANCE GAUTENG GAUTENG Johannesburg Pretoria JOHANNESBURG • Hillbrow • Rosettenville 12th Floor, Libridge Building 8th Floor, Olivetti House • Auckland Park • Jeppestown • Rouxville 25 Ameshoff street 100 Pretorius Street • Bellevue • Johannesburg CBD • Selby Braamfontein Cnr Pretorius & Schubart Str • Bellevue East • Joubert Park • Springs CBD Johannesburg, 2001 Pretoria, 0117 • Benoni • Judiths Paarl • Troyeville +27 (10) 595 9000 +27 (10) 595 9000 • Berea • Kempton Park CBD • Turf Club WELCOME • Bertrams • Kenilworth • Turffontein • Bezuidenhout KWAZULU NATAL • Kensington • Westdene Valley • Krugersdorp • Witpoortjie 27th Floor, Embassy Building • Boksburg North • La Rochelle • Yeoville TO TUHF 199 Anton Lembede Street • Braamfontein Durban, 4001 • Langbaagte • Brakpan +27 (31) 306 5036 • Lorentzville PRETORIA • Brixton • Marshall Town • Arcadia • City and Suburban • Melville • Capital Park CBD EASTERN CAPE • Doornfontein • New Doornfontein • Gezina CBD 2nd Floor, BCX Building • Fairview • Newtown • Hatfield 106 Park Drive • Florida • North Doornfontein • Pretoria CBD St. George’s Park • Forest Hill • Orange Grove • Pretoria North CBD Port Elizabeth, 6000 • Germiston • Primrose • Pretoria West +27 (41) 582 1450 • Highlands • Randburg CBD • Silverton CBD • Highlands North • Roodepoort • Sunnyside WESTERN CAPE KWAZULU NATAL 5th Floor South Block, Upper East Side 31 Brickfield Road DURBAN • Montclair • Wentworth Woodstock, • Albert Park • Overport Cape Town, 7925 • Bluff • Pinetown Central PIETERMARITZBURG +27 -

Exploring High Streets in Suburban Johannesburg

EXPLORING HIGH STREETS IN SUBURBAN JOHANNESBURG By Tatum Tahnee Kok A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Town and Regional Planning. Johannesburg, 2016 1 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation is my own unaided work. It is being submitted for the Degree of Master of Science to the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination to any other University. …………………………………………………………………………… (Signature of Candidate) ……….. Day of …………….., …………… (Day) (Month) (Year) 2 ABSTRACT Traditionally the high street serviced residents in the local suburb. The proliferation of entertainment and leisure activities on the high street in suburban Johannesburg has appealed to people in the broader region. These social spaces within the suburb provide a simultaneous interaction of individuals who can carry out their daily activities of shopping, dining and socializing and essentially has contributed to these high streets being successful destination points. Patrons, the foot traffic of the high street, sustain businesses on the high street. Some business owners neglect to implement city by-laws and comply with licensing regulations often perpetuating unfavourable circumstances for residents in the suburb. Noise, petty crime and parking constraints detract from the street's allure. Alternatively, some residents enjoy easy access to the street's activities. Using a mixed method research approach, this research reveals some of the perceptions, regulations and tensions regarding the prominence of entertainment and leisure activities on the high street. Three case studies (7th Street in Melville, 4th Avenue in Parkhurst and Rockey/Raleigh Street in Greater Yeoville) are explored to evaluate the role of entertainment and leisure on the suburban high street.