Technology and Big Data Meet the Risk of Terrorism in an Era of Predictive Policing and Blanket Surveillance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exhibit a Case 3:16-Cr-00051-BR Document 545-2 Filed 05/11/16 Page 2 of 86

Case 3:16-cr-00051-BR Document 545-2 Filed 05/11/16 Page 1 of 86 Exhibit A Case 3:16-cr-00051-BR Document 545-2 Filed 05/11/16 Page 2 of 86 Executive Order 12333 United States Intelligence Activities (As amended by Executive Orders 13284 (2003), 13355 (2004) and 134 70 (2008)) PREAMBLE Timely, accurate, and insightful information about the activities, capabilities, plans, and intentions of foreign powers , organizations, and persons, and their agents, is essential to the national security of the United States. All reasonable and lawful means must be used to ensure that the United States will receive the best intelligence possible. For that purpose, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, including the National Security Act of 1947, as amended, (Act) and as President of the United States of America, in order to provide for the effective conduct of United States intelligence activities and the protection of constitutional rights, it is hereby ordered as follows: PART 1 Goals, Directions, Duties, and Responsibilities with Respect to United States Intelligence Efforts 1.1 Goals. The United States intelligence effort shall provide the President, the National Security Council, and the Homeland Security Council with the necessary information on which to base decisions concerning the development and conduct of foreign, defense, and economic policies, and the protection of United States national interests from foreign security threats. All departments and agencies shall cooperate fully to fulfill this goal. (a} All means, consistent with applicable Federal law and this order, and with full consideration of the rights of United States persons, shall be used to obtain reliable intelligence information to protect the United States and its interests. -

İSTİHBARATIN TEŞKİLATLANMA Ve YÖNETİM SORUNSALI: A.B.D. ÖRNEĞİ

T.C. İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ SİYASET BİLİMİ VE KAMU YÖNETİMİ ANABİLİM DALI YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ İSTİHBARATIN TEŞKİLATLANMA ve YÖNETİM SORUNSALI: A.B.D. ÖRNEĞİ Fatih TÜRK 2501110836 TEZ DANIŞMANI DOÇ. DR Pelin Pınar GİRİTLİOĞLU İSTANBUL - 2019 ÖZ İSTİHBARATIN TEŞKİLATLANMA ve YÖNETİM SORUNSALI: A.B.D. ÖRNEĞİ Fatih TÜRK Günümüzde teknolojinin gelişimi ve küreselleşme dünyayı uçtan uca değiştirdi. Toplumlar ve ülkeler birbiri ile etkileşime geçtikçe bireysel özgürlükler ve demokrasi konusunda hassas alanlar giderek artmaktadır. Bu etkileşim ülkelerin güvenliğini ve bireysel özgürlük alanlarınıda etkilemektedir. Bu hızlı değişime karşın ülkeler geçmişin soğuk savaş anlayışı ve güvenlik hassasiyetlerini de aynı zamanda taşımaya devam etmektedirler. Gelişmiş demokrasilere sahip ülkelerin başında gelen Amerika Birleşik Devletleri’nde (ABD) mevcut güvenlik ve istihbarat anlayışı, faaliyetleri ve denetimi işte bu çatışmanın uzun sürede meydana geldiği denge üzerine kuruludur. ABD açısından istihbarat teşkilatlanma süreci yeni problemler, hak arayışları, çatışma ve çözümler doğurmaktadır. Tüm bunların ışığında bu tezin temel amacı istihbarat problemlerini ABD istihbarat teşkilatlanma süreci üzerinden analiz edip karşılaşılan problemleri neden sonuç ilişkisi içerisinde tespit etmektir. Bu çalışmada Amerika Birleşik Devletleri’nde istihbaratın yönetim modeli, teşkilatlanması ve hukuki alt yapısı incelenmiştir. Birinci bölümde kavramsal anlamda istihbarat incelemesi literatüre önemli bir katkı olarak görülebilir. İkinci bölümde -

The Surveillance State and National Security a Senior

University of California, Santa Cruz 32 Years After Orwellian “1984”: The Surveillance State and National Security A Senior Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of BACHELORS OF ARTS IN SOCIOLOGY AND LEGAL STUDIES by Ean L. Brown March 2016 Advisor: Professor Hiroshi Fukurai This work is dedicated to my dad Rex along with my family and friends who inspired me to go the extra mile. Special thanks to Francesca Guerra of the Sociology Department, Ryan Coonerty of the Legal Studies Department and Margaret Shannon of Long Beach City College for their additional advising and support. 2 Abstract This paper examines the recent National Security Agency (NSA) document leak by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden and analyzes select programs (i.e. PRISM, Dishfire, and Fairview) to uncover how the agency has maintained social control in the digital era. Such governmental programs, mining domestic data freely from the world’s top technology companies (i.e. Facebook, Google, and Verizon) and listening in on private conversations, ultimately pose a significant threat to the relation of person and government, not to mention social stability as a whole. The paper will also examine the recent government document leak The Drone Papers to detail and conceptualize how NSA surveillance programs are used abroad in Afghanistan, Somalia and Yemen. Specifically, this work analyzes how current law is slowly eroding to make room for the ever-increasing surveillance on millions of innocent Americans as well as the changing standard of proof through critical analysis of international law and First and Fourth Amendment Constitutional law. -

Global Surveillance Network

GCHQ and UK Mass Surveillance Chapter 4 4 A Global Surveillance Network 4.1 Introduction The extent of the collaboration between British and American signal intelligence agencies since World War II was long suspected, but it has been incontrovertibly exposed by Edward Snowden. The NSA and GCHQ operate so closely that they resemble a single organisation in many aspects, with an extremely close relationship with the other three members of the Five Eyes pact: Canada, Australia, New Zealand. Since the end of the Cold War, the network of collaboration around the Five Eyes has grown to the point where we can speak of a global surveillance complex with most countries willing to be part of the club. According to security experts, this is driven by the same network effects that create the Google monopoly.i Given that many details of these arrangements remain secret, it is hard to see how parliament and courts in one country can ever hope to rein them in. This creates practical problems for understanding the extent of intrusiveness of any surveillance, because we do not know who has access to the information. It is possible that US agencies that work closely with the NSA, such as the FBI, have access to more information from GCHQ than British police. In the other direction, the UK intelligence services are not constrained by any publicly available legislation in obtaining unsolicited intercepted material from other countries, even where the communications in question belong to people within the UK. But despite these levels of collaboration, the US takes an exceptionalist approach to rights, where citizens from other countries are not given sufficient legal protections from surveillance. -

Loopholes for Circumventing the Constitution: Unrestrained Bulk Surveillance on Americans by Collecting Network Traffic Abroad

Loopholes for Circumventing the Constitution: Unrestrained Bulk Surveillance on Americans by Collecting Network Traffic Abroad Axel Arnbak and Sharon Goldberg* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 2 A. Overview .............................................................................. 3 II. LOOPHOLES IN THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK ........................................ 9 A. First Regulatory Regime: ‘Patriot Act Section 215’. Domestic Communications, Surveillance on U.S. Soil. ............................................................................. 12 B. Second Regulatory Regime: ‘FISA’. International Communications, Surveillance On U.S. Soil. ............ 14 1. Overview. ................................................................ 14 * Axel Arnbak is a Faculty Researcher at the Institute for Information Law, University of Amsterdam and a Research Affiliate at the Berkman Center for Internet & Society, Harvard University. Sharon Goldberg is Assistant Professor of Computer Science, Boston University and a Research Fellow, Sloan Foundation. She gratefully acknowledges the support of the Sloan Foundation. Both authors thank Timothy H. Edgar, Ethan Heilman, Susan Landau, Alex Marthews, Bruce Schneier, Haya Shulman, Marcy Wheeler and various attendees of the PETS’14 and TPRC’14 conferences for discussions and pointers that have greatly aided this work. Alexander Abdo, David Choffnes, Nico van Eijk, Edward Felten, Daniel K. Gillmore, Jennifer Rexford, Julian -

Biblioteca Digital

Universidad de Buenos Aires Facultades de Ciencias Económicas, Ciencias Exactas y Naturales e Ingeniería Carrera de Especialización en Seguridad Informática Trabajo Final “Vigilancia masiva y manipulación de la opinión pública” Autor: Ing. Juan Ignacio Schab Tutor: Dr. Pedro Hecht Año de presentación: 2020 Cohorte 2018 Declaración Jurada del origen de los contenidos Por medio de la presente, el autor manifiesta conocer y aceptar el Reglamento de Trabajos Finales vigente y se hace responsable que la totalidad de los contenidos del presente documento son originales y de su creación exclusiva, o bien pertenecen a terceros u otras fuentes, que han sido adecuadamente referenciados y cuya inclusión no infringe la legislación Nacional e Internacional de Propiedad Intelectual. Ing. Juan Ignacio Schab DNI 37.338.256 Resumen Dos escándalos de gran repercusión internacional han contribuido para probar la real dimensión de los dos temas que dan título al presente trabajo. El primero de ellos fue la revelación de miles de documentos clasificados de agencias de inteligencia, principalmente estadounidenses, realizada por Edward Snowden, ex contratista de la CIA y la NSA, en el año 2013, la cual dio detalles de la extendida y profunda vigilancia masiva a escala global, la cual destruye el derecho a la privacidad y limita las libertades individuales. El otro hecho fue la participación de la empresa Cambridge Analytica en procesos electorales de distintos países del mundo, especialmente en las elecciones presidenciales de Estados Unidos en 2016 y en el referéndum para la salida de Gran Bretaña de la Unión Europea en el mismo año, revelada por ex trabajadores de la misma y por investigaciones de medios de comunicación, el cual permitió dar detalles sobre la capacidad de manipulación de la opinión pública principalmente a través de redes sociales. -

Lock Down on Prison Planet Almost Complete – American Intelligence Media

10/17/2017 Lock Down on Prison Planet Almost Complete – American Intelligence Media AMERICAN INTELLIGENCE MEDIA Citizens AIM for TRUTH ANONYMOUS PATRIOTS / OCTOBER 16, 2017 @ 4 32 PM LOCK DOWN ON PRISON PLANET ALMOST COMPLETE https://aim4truth.org/2017/10/16/lock-down-on-prison-planet-almost-complete/ 1/36 10/17/2017 Lock Down on Prison Planet Almost Complete – American Intelligence Media HOW THE US MILITARY CONTROL OF SOCIAL MEDIA HAS ALREADY IMPRISONED YOU AND THROWN AWAY THE KEY https://aim4truth.org/2017/10/16/lock-down-on-prison-planet-almost-complete/ 2/36 10/17/2017 Lock Down on Prison Planet Almost Complete – American Intelligence Media Long before we could imagine the evil of the elite pedophile globalists of the world, they had already started locking down planet earth. They knew that humanity’s wakening consciousness would jeopardize their planetary reign so they had to nd a way to imprison our minds, direct our thinking, and limit our expanding consciousness. They did it right under our noses. They did it with our own hard-earned money. While we were busy rearing our children and tending our families, they were quietly implementing Alinsky’s rules and Soros’ regimes. They are evil people who prey on our children, prot from our blood, rape our women and countries, and control us with their money illusions. They don’t care about our national borders, cultural uniqueness, spiritual paths, or personal liberty. YOU are THEIRS to be “farmed” any way that brings them greater wealth, longer life, and wicked pleasures. You have now awakened and realized that the nightmare is actually on the other side of your dreamy sleep. -

Amicus Briefs on Behalf of Itself and Others in Cases Involving

Case: 13-50572, 11/05/2015, ID: 9745936, DktEntry: 25, Page 1 of 47 13-50572 IN THE United States Court of Appeals FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT dUNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellee, —v.— BASAALY MOALIN, Defendant-Appellant. ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA CASE NO.10-CR-4246 HONORABLE JEFFREY T. MILLER, SENIOR DISTRICT JUDGE BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE, AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION, ELECTRONIC PRIVACY INFORMATION CENTER, FREEDOM TO READ FOUNDATION, NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF CRIMINAL DEFENSE LAWYERS, NINTH CIRCUIT FEDERAL AND COMMUNITY DEFENDERS, REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANT-APPELLANT AND REVERSAL MICHAEL PRICE* FAIZA PATEL BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE AT NEW YORK UNIVERSITY AT NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW SCHOOL OF LAW 161 Avenue of the Americas 161 Avenue of the Americas New York, New York 10013 New York, New York 10013 (646) 292-8335 (646) 292-8325 *Counsel of Record Attorneys for Amici Curiae Brennan Center for Justice, American Library Association, and Freedom to Read Foundation (Counsel continued on inside cover) Case: 13-50572, 11/05/2015, ID: 9745936, DktEntry: 25, Page 2 of 47 ALAN BUTLER LISA HAY ELECTRONIC PRIVACY INFORMATION FEDERAL PUBLIC DEFENDER CENTER (EPIC) DISTRICT OF OREGON 1718 Connecticut Avenue NW One Main Place Washington, DC 20009 101 Southwest Main Street, (202) 483-1140 Room 1700 Portland, Oregon 97204 DAVID M. PORTER (503) 326-2123 CO-CHAIR, NACDL AMICUS COMMITTEE HEATHER ERICA WILLIAMS 801 I Street, 3rd Floor FEDERAL PUBLIC DEFENDER Sacramento, California 95814 EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA (916) 498-5700 801 I Street, 3rd Floor Sacramento, California 95814 BRUCE D. -

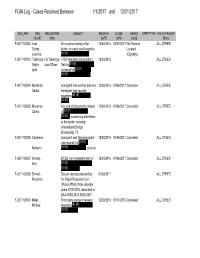

Department of State FOIA Log 2017

FOIA Log - Cases Received Between 1/1/2017 and 12/31/2017 REQ_REF REQ REQUESTER SUBJECT RECEIVE CLOSE GRANT EXEMPTIONS FEE CATEGORY NAME ORG DATE DATE CODE DESC F-2017-00002 Leal All records relating to the 12/30/2016 02/27/2017 No Records ALL OTHER Oteiza, border crossing card issued to Located Lourdes (b) (6) . (Oglesby) F-2017-00003 Tabangay-Fel Tabangay I-130 immigrant visa petition 12/30/2016 ALL OTHER Vigilla, Law Offices filed by (b) (6) April on behalf of (b) (6) (b) (6) F-2017-00004 Monarrez, Immigrant visa petition and non- 12/30/2016 01/06/2017 Cancelled ALL OTHER Carlos immigrant visa records regarding (b) (6) (b) (6) F-2017-00005 Monarrez, Any and all documents related 12/30/2016 01/06/2017 Cancelled ALL OTHER Carlos to (b) (6) (b) (6) concerning detentions at the border crossing International Bridge Brownsville, TX F-2017-00006 Cardenas Immigrant and Non-immigrant 12/30/2016 01/06/2017 Cancelled ALL OTHER , visa records for (b) (6) Norberto (b) (6) records F-2017-00007 Arocha, B1/B2 non-immigrant visa for 12/30/2016 01/06/2017 Cancelled ALL OTHER Ana (b) (6) (b) (6) F-2017-00008 Emmel, Special reports produced by 01/03/2017 ALL OTHER Benjamin the Rapid Response Unit (Public Affairs) from calendar years 2015-2016, described in DAA-0059-2013-0008-0001 F-2017-00010 Miller, Third party passport request 12/29/2016 01/17/2018 Cancelled ALL OTHER Michael regarding (b) (6) (b) (6) REQ_REF REQ REQUESTER SUBJECT RECEIVE CLOSE GRANT EXEMPTIONS FEE CATEGORY NAME ORG DATE DATE CODE DESC F-2017-00011 Cabrera, Cables, files, and documents -

Loopholes for Circumventing the Constitution: Unrestrained Bulk Surveillance on Americans by Collecting Network Traffic Abroad Axel Arnbak University of Amsterdam

Michigan Telecommunications and Technology Law Review Volume 21 | Issue 2 2015 Loopholes for Circumventing the Constitution: Unrestrained Bulk Surveillance on Americans by Collecting Network Traffic Abroad Axel Arnbak University of Amsterdam Sharon Goldberg Boston University Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.umich.edu/mttlr Part of the Communications Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, National Security Law Commons, President/Executive Department Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Axel Arnbak & Sharon Goldberg, Loopholes for Circumventing the Constitution: Unrestrained Bulk Surveillance on Americans by Collecting Network Trafficbr A oad, 21 Mich. Telecomm. & Tech. L. Rev. 317 (2015). Available at: http://repository.law.umich.edu/mttlr/vol21/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Telecommunications and Technology Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOOPHOLES FOR CIRCUMVENTING THE CONSTITUTION: UNRESTRAINED BULK SURVEILLANCE ON AMERICANS BY COLLECTING NETWORK TRAFFIC ABROAD Axel Arnbak and Sharon Goldberg* Cite as: Axel Arnbak and Sharon Goldberg, Loopholes for Circumventing the Constitution: Unrestrained Bulk Surveillance on Americans by Collecting Network Traffic Abroad, 21 MICH. TELECOMM. & TECH. L. REV. 317 (2015). This manuscript may be accessed online at repository.law.umich.edu. ABSTRACT This Article reveals interdependent legal and technical loopholes that the US intelligence community could use to circumvent constitutional and statutory safeguards for Americans. These loopholes involve the collection of Internet traffic on foreign territory, and leave Americans as unprotected as foreigners by current United States (US) surveillance laws. -

The Snowden Affair”

Lessons from “the Snowden Affair” @haroonmeer September 2014 What this talk is not IT DOESN’T MATTER CREST BUGSY CRISSCROSS A-PLUS BULLRUN DYNAMO GUMFISH LFS-2 CROSSBEAM ACRIDMINI BULLSEYE EBSR GURKHASSWORD LHR CROSSEYEDSLOTH AGILEVIEW BUMBLEBEEDANCE EDGEHILL HACIENDA LIFESAVER CRUMPET AGILITY BYSTANDER EINSTEIN HAMMERMILL LITHIUM CRYOSTAT AIGHANDLER BYZANTINEANCHOR ELATE HAPPYFOOT LOCKSTOCK CRYPTOENABLED AIRBAG BYZANTINEHADES ELEGANTCHAOS HAWKEYE LONGHAUL CULTWEAVE AIRGAP/COZEN CADENCE ENDUE HC12 LONGRUN CUSTOMS AIRWOLF CANDYGRAM ENTOURAGE HEADMOVIES LONGSHOT CYBERCOMMANDCONSOLE ALLIUMARCH CANNONLIGHT EVENINGEASEL HIGHCASTLE LOPERS CYCLONE ALTEREGOQFD CAPTIVATEDAUDIENCE EVILOLIVE HIGHLANDS LUMP DANCINGBEAR ANCESTRY CARBOY EWALK HIGHTIDE LUTEUSICARUS DANCINGOASIS ANCHORY CASPORT EXCALIBUR HOLLOWPOINT MADCAPOCELOT DAREDEVIL ANTICRISISGIRL CASTANET EXPOW HOMEBASE MAGNETIC DARKFIRE ANTOLPPROTOSSGUI CCDP FACELIFT HOMEPORTAL MAGNUMOPUS DARKQUEST APERTURESCIENCE CDRDIODE FAIRVIEW HOMINGPIGEON MAINCORE DARKTHUNDER AQUADOR CERBERUS FALLOUT HUSHPUPPY MAINWAY ARTEMIS CERBERUSSTATISTICSCOLLECTION! FASCIA HUSK MARINA DEADPOOL ARTIFICE CHALKFUN FASHIONCLEFT IBIS MAUI DEVILSHANDSHAKE ASPHALT CHANGELING FASTSCOPE ICE MESSIAH DIALD ASSOCIATION CHAOSOVERLORD FATYAK ICREACH METROTUBE DIKTER ASTRALPROJECTION CHASEFALCON FET ICREAST METTLESOME DIRTYEVIL AUTOSOURCE CHEWSTICK FISHBOWL IMP MINERALIZE DISCOROUTE AXLEGREASE CHIPPEWA FOGGYBOTTOM INCENSER MINIATUREHERO DISHFIRE BABYLON CHOCOLATESHIP FORESTWARRIOR INDRA MIRAGE DISTANTFOCUS BALLOONKNOT CIMBRI FOXACID -

La Surveillance De Masse Dans Le Cyber Espace : La Reponse Securitaire Des Etats-Unis Au Terrorisme Djihadiste

Université de Lyon Institut d’Etudes Politiques de Lyon LA SURVEILLANCE DE MASSE DANS LE CYBER ESPACE : LA REPONSE SECURITAIRE DES ETATS-UNIS AU TERRORISME DJIHADISTE EL OUED Jihène M1 Affaires Internationales Risques internationaux et nouveaux paradigmes de la sécurité 2016-2017 Sous la direction de Tawfik Bourgou 2 | LA SURVEILLANCE DE MASSE DANS LE CYBER ESPACE : LA REPONSE SECURITAIRE DES ETATS-UNIS AU TERRORISME DJIHADISTE 3 | Déclaration anti-plagiat 1. Je déclare que ce travail ne peut être suspecté de plagiat. Il constitue l’aboutissement d’un travail personnel. 2. A ce titre, les citations sont identifiables (utilisation des guillemets lorsque la pensée d’un auteur autre que moi est reprise de manière littérale). 3. L’ensemble des sources (écrits, images) qui ont alimenté ma réflexion sont clairement référencées selon les règles bibliographiques préconisées. NOM : EL OUED PRENOM : Jihène DATE : 03/08/2017 4 | Liste des acronymes Anglophones CIA – Central Intelligence Agency COIN – Counter Insurgency COINTELPRO – Counter Intelligence Program CYBERCOM – United States Cyber Command DNI – Director of National Intelligence DDoS – Distributed Denial of Services DoD – Department of Justice FBI – Federal Bureau of Investifation FISA – Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act NCTC – National Counterterrorism Center NSA – National Security Agency RMA – Revolution in Military Affairs Francophones EI – Etat islamiste NTIC – Nouvelles technologies de l’information et de la communication 5 | Propos liminaires « La pleine lumière et le regard d’un surveillant captent mieux que l’ombre, qui finalement protégeait. La visibilité est un piège. » - FOUCAULT, Michel. Surveiller et punir, 1st ed. Paris : Gallimard, 1975, p.233-234 6 | Introduction La lutte contre le terrorisme est une constante de la politique de défense américaine.