Acoustics of Palaeolithic Caves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Den Himmel Stützen! Prozeß, Kognition, Macht, Geschlecht - Soziologische Reflexionen Zum Jung- Paläolithikum Hennings, Lars

www.ssoar.info Den Himmel stützen! Prozeß, Kognition, Macht, Geschlecht - soziologische Reflexionen zum Jung- Paläolithikum Hennings, Lars Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Hennings, L. (2014). Den Himmel stützen! Prozeß, Kognition, Macht, Geschlecht - soziologische Reflexionen zum Jung-Paläolithikum. Berlin. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-383212 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Basic Digital Peer Publishing-Lizenz This document is made available under a Basic Digital Peer zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den DiPP-Lizenzen Publishing Licence. For more Information see: finden Sie hier: http://www.dipp.nrw.de/lizenzen/dppl/service/dppl/ http://www.dipp.nrw.de/lizenzen/dppl/service/dppl/ Den Himmel stützen! Prozeß, Kognition, Macht, Geschlecht – soziologische Reflexionen zum Jung-Paläolithikum Lars Hennings Berlin 2014 Den Himmel stützen! Prozeß, Kognition, Macht, Geschlecht – soziologische Reflexionen zum Jung-Paläolithikum Lars Hennings Jede Form des Kopierens – Text und Abbildungen – ist untersagt. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Berlin 2014 ISBN 978-1-291-84271-5 29.04.14 frei > www.LarsHennings.de [email protected] 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis Kasten A: Zeiträume .....................................................................4 Annäherung an eine Soziologie der Steinzeit ................................................5 Grundlagen .........................................................................................8 -

Homo Aestheticus’

Conceptual Paper Glob J Arch & Anthropol Volume 11 Issue 3 - June 2020 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Shuchi Srivastava DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2020.11.555815 Man and Artistic Expression: Emergence of ‘Homo Aestheticus’ Shuchi Srivastava* Department of Anthropology, National Post Graduate College, University of Lucknow, India Submission: May 30, 2020; Published: June 16, 2020 *Corresponding author: Shuchi Srivastava, Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, National Post Graduate College, An Autonomous College of University of Lucknow, Lucknow, India Abstract Man is a member of animal kingdom like all other animals but his unique feature is culture. Cultural activities involve art and artistic expressions which are the earliest methods of emotional manifestation through sign. The present paper deals with the origin of the artistic expression of the man, i.e. the emergence of ‘Homo aestheticus’ and discussed various related aspects. It is basically a conceptual paper; history of art begins with humanity. In his artistic instincts and attainments, man expressed his vigour, his ability to establish a gainful and optimistictherefore, mainlyrelationship the secondary with his environmentsources of data to humanizehave been nature. used for Their the behaviorsstudy. Overall as artists findings was reveal one of that the man selection is artistic characteristics by nature suitableand the for the progress of the human species. Evidence from extensive analysis of cave art and home art suggests that humans have also been ‘Homo aestheticus’ since their origins. Keywords: Man; Art; Artistic expression; Homo aestheticus; Prehistoric art; Palaeolithic art; Cave art; Home art Introduction ‘Sahityasangeetkalavihinah, Sakshatpashuh Maybe it was the time when some African apelike creatures to 7 million years ago, the first human ancestors were appeared. -

HYBRID BEINGS and REPRESENTATION of POWER in the PREHISTORIC PERIOD PREHISTORİK DÖNEMDE KARIŞIK VARLIKLAR VE GÜCÜN TEMSİLİ Sevgi DÖNMEZ

TAD, C. 37/ S. 64, 2018, 97-124. HYBRID BEINGS AND REPRESENTATION OF POWER IN THE PREHISTORIC PERIOD PREHISTORİK DÖNEMDE KARIŞIK VARLIKLAR VE GÜCÜN TEMSİLİ Sevgi DÖNMEZ Makale Bilgisi Article Info Başvuru:31 Ocak 2018 Recieved: January 21, 2018 Kabul: 29 Haziran 2018 Accepted: June 29, 2018 Abstract A great change in humankind's cognitive and symbolic world with the start of the Upper Paleolithic period around 40 thousand B.C.E. Depicted works of art describing hybrid creatures have emerged during the Upper Paleolithic period in parallel with emergence of hunter cultures. Ancient forms of Shamanism, a popular belief system among hunter cultures, had an effect on emergence of these hybrid figures. Imitation of the strong and the intelligent within the animal kingdom and the humankind's thirst for merging developing its physical and intellectual capacity with this power are among the main dynamics behind emergence of hybrid figures. The humankind of the Upper Paleolithic period, which has seen the world with a sense of permeability among species and an animalistic sensitivity and vigor, had a cognitive world within which things and humans must have been at the same level and forming a unity. During breakage of this unity and a sense of "togetherness," the hunter tries to balance the fear and suspense caused by prohibition of violence against those that exist at the same level and spiritual unity with mythical thinking. Prohibition of violence gave way to a cognitive status that identifies with the prey. This new symbolic consciousness which has emerged during the Upper Paleolithic period has tried to find a balance between controlling the suspense and fear caused by violence directed against the strong and the wild and the strength of the victim. -

Les Matières Colorantes Au Début Du Paléolithique Supérieur : Sources, Transformations Et Fonctions Hélène Salomon

Les matières colorantes au début du Paléolithique supérieur : sources, transformations et fonctions Hélène Salomon To cite this version: Hélène Salomon. Les matières colorantes au début du Paléolithique supérieur : sources, transforma- tions et fonctions. Archéologie et Préhistoire. Université Bordeaux 1, 2009. Français. tel-02430482 HAL Id: tel-02430482 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02430482 Submitted on 7 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. N◦ d’ordre : 3971 THÈSE présentée à L’UNIVERSITÉ BORDEAUX 1 ÉCOLE DOCTORALE :SCIENCES ET ENVIRONNEMENTS par Hélène SALOMON POUR OBTENIR LE GRADE DE DOCTEUR Spécialité : Préhistoire LES MATIÈRES COLORANTES AU DÉBUT DU PALÉOLITHIQUE SUPÉRIEUR S OURCES, TRANSFORMATIONS ET FONCTIONS Soutenue publiquement le 22 décembre 2009 Après avis de : M. Pierre Bodu Chargé de Recherche CNRS ArcScAn-Nanterre Rapporteur M. Marcel Otte Professeur de préhistoire Université de Liège Rapporteur Devant la commission d’examen formée de : M. Pierre Bodu Chargé de Recherche, CNRS ArcScAn-Nanterre Rapporteur M. Francesco d’Errico Directeur de Recherche CNRS PACEA, Université Bordeaux 1 Examinateur M. Jean-Michel Geneste Conservateur du Patrimoine, Directeur du CNP Périgueux et PACEA Universiré Bordeaux 1 Directeur de thèse M. -

Symbolic Territories in Pre-Magdalenian Art?

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321909484 Symbolic territories in pre-Magdalenian art? Article in Quaternary International · December 2017 DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2017.08.036 CITATION READS 1 61 2 authors, including: Eric Robert Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle 37 PUBLICATIONS 56 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: An approach to Palaeolithic networks: the question of symbolic territories and their interpretation through Magdalenian art View project Karst and Landscape Heritage View project All content following this page was uploaded by Eric Robert on 16 July 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Quaternary International 503 (2019) 210e220 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Symbolic territories in pre-Magdalenian art? * Stephane Petrognani a, , Eric Robert b a UMR 7041 ArscAn, Ethnologie Prehistorique, Maison de l'Archeologie et de l'Ethnologie, Nanterre, France b Departement of Prehistory, Museum national d'Histoire naturelle, Musee de l'Homme, 17, place du Trocadero et du 11 novembre 75116, Paris, France article info abstract Article history: The legacy of specialists in Upper Paleolithic art shows a common point: a more or less clear separation Received 27 August 2016 between Magdalenian art and earlier symbolic manifestations. One of principal difficulty is due to little Received in revised form data firmly dated in the chronology for the “ancient” periods, even if recent studies precise chronological 20 June 2017 framework. Accepted 15 August 2017 There is a variability of the symbolic traditions from the advent of monumental art in Europe, and there are graphic elements crossing regional limits and asking the question of real symbolic territories existence. -

The Meaning of the Dots on the Horses of Pech Merle

Arts 2013, 2, 476-490; doi:10.3390/arts2040476 OPEN ACCESS arts ISSN 2076-0752 www.mdpi.com/journal/arts Article The Meaning of the Dots on the Horses of Pech Merle Barbara Olins Alpert Professor Rhode Island School of Design, retired, 70 Esplanade, Middletown, RI 02842, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-401-847-4909 Received: 26 September 2013; in revised form: 19 November 2013 / Accepted: 20 November 2013 / Published: 13 December 2013 Abstract: Recent research in the DNA of prehistoric horses has resulted in a new interpretation of the well-known panel of the Spotted horses of Pech Merle. The conclusion that has been popularized by this research is that the artists accurately depicted the animals as they saw them in their environment. It has long been evident that some artists of the European Ice Age caves were able to realize graphic memesis to a remarkable degree. This new study of the genome of ancient horses appears to confirm the artist’s intention of creating the actual appearance of dappled horses. I will question this conclusion as well as the relevance of this study to the art by examining the Spotted horses in the context of the entire panel and the panel in the context of the whole cave. To further enlarge our view, I will consider the use of similar dots and dappling in the rock art of other paleolithic people. The visual effect of dots will be seen in terms of their psychological impact. Discoveries by neuroscientists regarding the effect of such stimuli on human cognition will be mentioned. -

Guide Pèlerins

GUIDE PÈLERINS GR®65 - GR®651 - GR®36/46 LE CHEMIN DE SAINT-JACQUES-DE-COMPOSTELLE DE LIMOGNE-EN-QUERCY À MONTLAUZUN e Lot ouvre ses chemins aux pèlerins en marche vers L Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle. Le sud du département est traversé d’est en ouest par la Via Podiensis, ou voie du Puy-en-Velay, aujourd’hui devenue GR®65. Il se trouve aussi à la croisée de 2 itinéraires supplémentaires : le GR®651, variante de la vallée du Célé, et le GR®46 venant de Rocamadour. GR®65 u St Jean-de-Laur/Limogne-en-Quercy 9 km u Limogne-en-Quercy/Varaire 8 km u Varaire/Vaylats 9 km u Vaylats/Flaujac-Poujols 20 km u Flaujac-Poujols/Cahors 9 km GR®651 u Cahors/Labastide-Marnhac 12 km u Labastide-Marnhac/Lascabanes 12 km u Marcilhac-sur-Célé/Cabrerets 19 km u Lascabanes/Montcuq 9 km u Cabrerets/Conduché 5 km u Montcuq/Montlauzun 7 km u Conduché/Bouziès 2 km GR®36/46 GR®36 u Bouziès/St Cirq Lapopie 4 km u Bouziès/Pasturat 12 km u St Cirq Lapopie/Concots 9 km u Pasturat/Vers 6 km u Concots/Bach 8 km u Vers/Cahors 21 km u Bach/Cahors 17 km De Limogne-en-Quercy à Montlauzun 4 étapes majeures Limogne-en-Quercy Limogne-en-Quercy est un bourg typique des Causses du Quercy et possède un important patrimoine vernaculaire. Dolmens, murets de pierre sèche, lavoirs et croix de chemin sont nombreux, visibles au hasard des chemins. Ses commerces, ses restaurants et ses terrasses lui donnent des airs de petite ville, avec une particularité : un marché aux truffes d’été du 1er dimanche de juin à mi-août, et un marché aux truffes d’hiver le vendredi de décembre à mars (10h30). -

C99 Official Journal

Official Journal C 99 of the European Union Volume 63 English edition Information and Notices 26 March 2020 Contents II Information INFORMATION FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2020/C 99/01 Non-opposition to a notified concentration (Case M.9701 — Infravia/Iliad/Iliad 73) (1) . 1 2020/C 99/02 Non-opposition to a notified concentration (Case M.9646 — Macquarie/Aberdeen/Pentacom/JV) (1) . 2 2020/C 99/03 Non-opposition to a notified concentration (Case M.9680 — La Voix du Nord/SIM/Mediacontact/Roof Media) (1) . 3 2020/C 99/04 Non-opposition to a notified concentration (Case M.9749 — Glencore Energy UK/Ørsted LNG Business) (1) . 4 IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2020/C 99/05 Euro exchange rates — 25 March 2020 . 5 2020/C 99/06 Summary of European Commission Decisions on authorisations for the placing on the market for the use and/or for use of substances listed in Annex XIV to Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) (Published pursuant to Article 64(9) of Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006) (1) . 6 EN (1) Text with EEA relevance. V Announcements PROCEDURES RELATING TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF COMPETITION POLICY European Commission 2020/C 99/07 Prior notification of a concentration (Case M.9769 — VW Group/Munich RE Group/JV) Candidate case for simplified procedure (1) . 7 OTHER ACTS European Commission 2020/C 99/08 Publication of a communication of approval of a standard amendment to a product specification for a name in the wine sector referred to in Article 17(2) and (3) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/33 . -

Le Grand Cahors

Programme Local de l’Habitat (PLH) 2018 - 2023 Bureau CRHH Le 15 Mai 2018, Carcassonne ARCAMBAL BELLEFONT -LA -RAUZE BOISSIÈRES BOUZIÈS CABRERETS CAHORS CAILLAC CALAMANE CATUS CIEURAC CRAYSSAC DOUELLE ESPÈRE FONTANES FRANCOULÈS GIGOUZAC LES JUNIES LABASTIDE - DU -VERT LABASTIDE -MARNHAC LAMAGDELAINE LHERM MAXOU MECHMONT MERCUÈS LE MONTAT MONTGESTY NUZÉJOULS PONTCIRQ PRADINES SAINT -CIRQ -LAPOPIE SAINT -DENIS -CATUS SAINT -GÉRY -VERS SAINT -MÉDARD SAINT -PIERRE -LAFEUILLE TOUR -DE -FAURE TRESPOUX -RASSIELS L’ ARTICULATION ENTRE LE PLH DU GRAND CAHORS ET LES AUTRES DOCUMENTS STRATEGIQUES PLUI Projet de Territoire Porter à Gd Cahors du connaissance Grand Cahors Etat, PDH, Schémas 2015-2020 dptx PLH Gd Cahors SCOT de Cahors et du Sud du Lot LE GRAND CAHORS •De 8 à 36 communes Une jeune •41.300 habitants •593 km² agglomération •Cahors : préfecture du Lot •1er Projet de territoire en 2015 •56 % habitants dans le pôle urbain •1/3 de communes de moins de 300 Un territoire habitants pluriel •Des paysages et un patrimoine d’exception •Cahors: ville préfecture •Porté par les nouveaux arrivants •Lié à l’évolution des emplois Un dynamisme présentiels démographique •Ralentissement depuis 2008 •Un territoire vieillissant •Fort développement périurbain Accentuation •Personnes âgées sur Cahors et zone des rurale spécialisations •Familles en couronne périurbaine résidentielles •Repli des populations vulnérables sur le pôle urbain 3 CHIFFRES CLÉS / HABITAT Une consommation foncière soutenue 24.721 LOGEMENTS (INSEE 2014) (1 571 m²/lgt construit) et une -

CAHORS ST-CIRQ-LAPOPIE Le Lot CAJARC

LE LOT SANS VOITURE LE LOT SANS VOITURE CAHORS - ST CIRQ LAPOPIE 6 circuits de découverte sans ST-DENIS-LES-MARTEL voiture des grands sites du Lot SOUILLAC La Dordogne ST-CÉRÉ ROCAMADOUR GOURDON LACAPELLE-MARIVAL LABASTIDE-MURAT FIGEAC Le Célé ORNIAC PUY L’ÉVÊQUE CAHORS ST-CIRQ-LAPOPIE Le Lot CAJARC BACH LALBENQUE CAHORS ST-CIRQ-LAPOPIE Vous n'avez pas de voiture mais souhaitez découvrir ce département qui offre une diversité exceptionnelle d'espaces Découvrir la Vallée du Lot en BUS depuis Cahors et de sites : voici une proposition de circuits faite pour vous ! jusqu’au village perché de St-Cirq-Lapopie >> BUS TER - LIGNE 889 (CARS DELBOS) Vous avez aimé ? £ DÉPART 3 DURÉE GCOÛT € Retrouvrez aussi : Gare SNCF 45 minutes 6,70 / pers. de Cahors (25,4 km) par trajet St Cirq Lapopie - Figeac Figeac - Rocamadour Rocamadour - Souillac a HORAIRES Souillac - Gourdon Gourdon - Cahors 6h, 9h, 12h34, 17h27, 18h51, 20h28 LUNDI AU VENDREDI (du Lun au Jeu un horaire supp. à 20h20) sur www.tourisme-lot.com SAMEDI 6h, 9h, 12,34, 20h28 DIMANCHE & FÉRIÉS 9h, 14h10, 18h30, 20h28 PARTAGEZ VOS PHOTOS ⚠ Les horaires et tarifs sont susceptibles d'être modifiés, il est préférable AVEC #TOURISMELOTDORDOGNE ! de les confirmer sur le site TER.Occitanie Achetez votre billet sur www.ter.sncf.com/occitanie/acheter Cahors De la place du marché en passant par les terrasses du boulevard Gambetta, Cahors la capitale du Lot conjugue ambiance méridionale, richesses historiques et plaisirs gourmands pour séduire Saint Cirq Lapopie autant les passionnés Accroché sur une falaise à 100 mètres au-dessus du de patrimoine que les Lot, Saint-Cirq-Lapopie comptabilise 13 monuments amoureux d’art de vivre. -

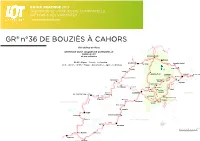

GR® N°36 DE BOUZIÈS À CAHORS

GUIDE PRATIQUE 2017 CHEMIN DE ST-JACQUES-DE-COMPOSTELLE GR® N°65 & SES VARIANTES www.tourisme-lot.com GR® n°36 DE BOUZIÈS À CAHORS Voie du Puy-en-Velay ne og rd o GR D 6 65 a 4 2 L CHEMIN DE SAINT JACQUES DE COMPOSTELLE R DANS LE LOT G et ses variantes ROCAMADOUR ! G R 2 6 65 !! Gramat 4 GR GR 65 : Figeac - Cahors - La Romieu GOURDON ! ! Lacapelle-Marival ! Le Vigan G GR 6 - GR 64 - GR 652 : Figeac - Rocamadour - Agen - La Romieu R 6 ! ! ! St Bressou Salviac lé é C Cazals e ! ! L 6 4 Labastide-Murat LOT R Espagnac FIGEAC Montredon G Ste Eulalie ! Béduer !! 65 ! ! GR Frayssinet-le-Gélat t ! Lo Montcabrier Marcilhac- 1 Le 65 ! ! sur-Célé ! GR Faycelles Cabrerets 65 ! ! GR t o L Puy-l'Evéque Luzech e Vers ! ! Bouziès L ! ! ! ! Cajarc St Cirq !! GR 36 Pasturat Lapopie Tournon CAHORS G AVEYRON VILLENEUVE SUR LOT d'Agenais R ! ! ! ! 3 Laburgade 6 ! ! Penne- Limogne-en-Quercy d'Agenais GR 6 2 Montcuq 5 ! GR 5 Varaire 36 6 ! ! ! Lascabanes ! Bach LOT ET GARONNE R G Vaylats 6 Montlauzun 4 ! R G ! Lauzerte La G aro nne !! AGEN Durfort-Lacapelette Roquefort! ! ! Moirax TARN ET GARONNE 5 GR 6 ! Aurillac ! ! MOISSAC 8 0 5 10 20 Km Source : Lot Tourisme - 2016 2 ! ! Miradoux 65 La Romieu GR !! CONDOM ! GERS Lectoure GR® n°36 DE BOUZIÈS À CAHORS BOUZIES – 46330 Chambres d’hôtes [email protected] Gîte d’étape Le Monde allant Vers Tél. 05 65 30 29 02 (mairie) Le Causse de Nezou (HORS GR) wwwlatruitedoree.fr Rue du château [email protected] Tél. -

Schéma D'aménagement Et De Gestion Des Eaux Du Bassin Du Célé

Schéma d’ Aménagement et de Gestion des Eaux du bassin du Célé CARTOGRAPHIE 24 allée V. Hugo - BP 118 46103 FIGEAC Cedex Tél : 05.65.11.47.65 Fax : 05.65.11.47.66 www.smbrc.com Version : mai 2011 - 2 - ! GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG ! "#$%&$GGGGG & " GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG # & ' ( " GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG ) #*+ + GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG , )- ! (GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG . ,*/ ! (GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG 1 .2 !3 %%&4%%,5GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG % 16 GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG % 7 " (!S/ " "/ 9 4 GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG 7 " !(!S/ " "/ 9 4 GGGGG 7 " !(("!S/ "/ 9 4 GGGGG & :7 "( (' !("/ / " 9 GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG # &:7 "( (' !("/ / 9 GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG ) # S !9 GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG, )2 ( ' !(/GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG . , ( / " 3 5GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG 1 .2 S GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG % 1 ( / GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG %! S S <&4, S !GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG ' ( GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG ' (GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG & 2 S !9 GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG # M - 3 - Direction Aurillac CARTE 1 Le Rouget St Mamet Géographie du bassin versant du Célé Direction aï z St-Céré CANTAL Bou re Latronquière lèg Mou Boisset Rance 22 D 217 Marcolès N 1 LOT r s D31 oi è e N Quézac n ru A et Ma Direction eau agu s D e 635 Sib Be ynh Brive St Cirgues ce e r uis n Le er vez sègu R g omb Ra s ue o Re s u Lacapelle Arc re y D 19 e Calvinet B V ur lan es