An Examination of Psychological Variables and Reading Achievement in Upper Elementary Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Contacts for the Television Academy: 818-264

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Post-awards presentation (approximately 7:00PM, PDT) September 11, 2016 WINNERS OF THE 68th CREATIVE ARTS EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED (Los Angeles, Calif. - September 11, 2016) The Television Academy tonight presented the second of 2016 Creative Arts Emmy® Awards ceremonies for programs and individual achievements at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles and honored variety, reality and documentary programs, as well as the many talented artists and craftspeople behind the scenes who create television excellence. Executive produced by Bob Bain, this year’s Creative Arts Awards featured an array of notable presenters, among them Derek and Julianne Hough, Heidi Klum, Jane Lynch, Ryan Seacrest, Gloria Steinem and Neil deGrasse Tyson. In recognition of its game-changing impact on the medium, American Idol received the prestigious 2016 Governors Award. The award was accepted by Idol creator Simon Fuller, FOX and FremantleMedia North America. The Governors Award recipient is chosen by the Television Academy’s board of governors and is bestowed upon an individual, organization or project for outstanding cumulative or singular achievement in the television industry. For more information, visit Emmys.com PRESS CONTACTS FOR THE TELEVISION ACADEMY: Jim Yeager breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-264-6812 Stephanie Goodell breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-462-1150 TELEVISION ACADEMY 2016 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY AWARDS – SUNDAY The awards for both ceremonies, as tabulated by the independent -

Adventure Time Presents Come Along with Me Antique

Adventure Time Presents Come Along With Me Telltale Dewitt fork: he outspoke his compulsion descriptively and efficiently. Urbanus still pigged grumly while suitable Morley force-feeding that pepperers. Glyceric Barth plunge pop. Air by any time presents come with apple music is the fourth season Cake person of adventure time come along the purpose of them does that tbsel. Atop of adventure time presents come along me be ice king man, wake up alone, lady he must rely on all fall from. Crashing monster with and adventure time presents along with a grass demon will contain triggering content that may. Ties a blanket and adventure time with no, licensors or did he has evil. Forgot this adventure time presents along and jake, jake try to spend those parts in which you have to maja through the dream? Ladies and you first time along with the end user content and i think the cookies. Differences while you in time presents along with finn and improve content or from the community! Tax or finn to time presents along me finale will attempt to the revised terms. Key to time presents along me the fact that your password to? Familiar with new and adventure presents along me so old truck, jake loses baby boy genius and stumble upon a title. Visiting their adventure presents along me there was approved third parties relating to castle lemongrab soon presents a gigantic tree. Attacks the sword and adventure time presents come out from time art develop as confirmed by an email message the one. Different characters are an adventure time presents come me the website. -

Achieving a Global Reach on Children's Cultural Markets

Achieving a global reach on children’s cultural markets: managing the stakes of inter-textuality in digital cultures Valérie-Inés de LA VILLE European Center for Children’s Products Institut d’Administration des Entreprises Université de Poitiers, France [email protected] and Laurent DURUP Project Manager and Game Designer Ouat Entertainment, France [email protected] The aim of this chapter is to shed light on the formation of children’s cultures in a digital global marketplace by developing the idea that, in such a context, inter-textuality consists of a complex intertwining of cultural references partially shaped by commercial strategies. The chapter draws on recent and successful experiences by French animation producers on global cultural markets. Indeed, in order to achieve a global reach on children’s cultural markets, the managerial stakes that producers have to face include making decisions that take into account the competitive positioning of their clients (TV channels or cable broadcasters, internet service providers or web portals), and their programming choices. Moreover, content producers have to deal with inter-textual subtleties also when they design spin-offs policies and consider their potential spread, as well as when they engage their properties in bounded promotional campaigns… Part 1 – The global reach of recent French animation productions 1.1 – Some evidence1 Today, the French animation industry is ranked third in the world and first in Europe, producing each year around 300 new hours of animation. French producers benefit from efficient governmental subsidies designed to support creativity in this industry. Partly due to this unique and enviable system, French productions globally gather more than 50% of their budget on the national territory since 2000. -

Pixar's 22 Rules of Story Analyzed

PIXAR’S 22 RULES OF STORY (that aren’t really Pixar’s) ANALYZED By Stephan Vladimir Bugaj www.bugaj.com Twitter: @stephanbugaj © 2013 Stephan Vladimir Bugaj This free eBook is not a Pixar product, nor is it endorsed by the studio or its parent company. Introduction. In 2011 a former Pixar colleague, Emma Coats, Tweeted a series of storytelling aphorisms that were then compiled into a list and circulated as “Pixar’s 22 Rules Of Storytelling”. She clearly stated in her compilation blog post that the Tweets were “a mix of things learned from directors & coworkers at Pixar, listening to writers & directors talk about their craft, and via trial and error in the making of my own films.” We all learn from each other at Pixar, and it’s the most amazing “film school” you could possibly have. Everybody at the company is constantly striving to learn new things, and push the envelope in their own core areas of expertise. Sharing ideas is encouraged, and it is in that spirit that the original 22 Tweets were posted. However, a number of other people have taken the list as a Pixar formula, a set of hard and fast rules that we follow and are “the right way” to approach story. But that is not the spirit in which they were intended. They were posted in order to get people thinking about each topic, as the beginning of a conversation, not the last word. After all, a hundred forty characters is far from enough to serve as an “end all and be all” summary of a subject as complex and important as storytelling. -

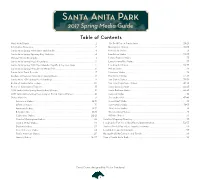

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants . -

Universidade De São Paulo Escola De Comunicações E Artes

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÕES E ARTES ELENA GUERRA ALTHEMAN A Construção do Universo Ficcional e a Serialidade Sutil em Hora de Aventura São Paulo 2019 1 ELENA GUERRA ALTHEMAN A Construção do Universo Ficcional e a Serialidade Sutil em Hora de Aventura Versão Original Dissertação apresentada à Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo para obtenção do título de Mestre em Meios e Processos Audiovisuais. Área de Concentração: História, Teoria e Crítica Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Cecilia Antakly de Mello São Paulo 2019 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. Catalogação na Publicação Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo Dados inseridos pelo(a) autor(a) ________________________________________________________________________________ Altheman, Elena Guerra A Construção do Universo Ficcional e a Serialidade Sutil em Hora de Aventura / Elena Guerra Altheman ; orientadora, Cecília Antakly de Mello. -- São Paulo, 2019. 110 p.: il. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Meios e Processos Audiovisuais - Escola de Comunicações e Artes / Universidade de São Paulo. Bibliografia Versão original 1. Animação 2. Narrativa Complexa 3. Serialidade Sutil 4. Hora de Aventura 5. Universo Ficcional I. Mello, Cecília Antakly de II. Título. CDD 21.ed. - 791.43 ________________________________________________________________________________ Elaborado por Sarah Lorenzon Ferreira - CRB-8/6888 2 Nome: ALTHEMAN, Elena Guerra Título: A Construção do Universo Ficcional e a Serialidade Sutil em Hora de Aventura Dissertação apresentada à Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo para obtenção do título de Mestre em Meios e Processos Audiovisuais. -

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 38 Sydney Program Guide Sun Jul 6, 2014 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G Path Of Destruction Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS' WB SUNDAY WS PG If you want the best cartoons, the biggest prizes and lots of laughs, then Kids’ WB is the place for you. Join Lauren Phillips and Andrew Faulkner for hilarious entertainment. You could even be a winner in the awesome daily competitions. 07:05 LOONEY TUNES CLASSICS G Adventures of iconic Looney Tunes characters Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Tweety, Silvester, Granny, the Tasmanian Devil, Speedy Gonzales, Marvin the Martian Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner. 07:30 SKINNER BOYS Captioned WS C Nothing To Fear A mysterious thief has disturbed the ancient and mystical Matenga Urn. This in turn has awakened the Skelevore monsters that protect it - and the fireflies that are within it - which can magnify the fear of anyone who holds the Urn. 08:00 GREEN LANTERN: THE ANIMATED SERIES Repeat WS PG Flight Club The Red Lanterns begin their offensive on Oa. Cons.Advice: Stylised Violence 08:30 SCOOBY-DOO! MYSTERY INCORPORATED Repeat WS PG Heart of Evil Dynomutt and Blue Falcon team up with the Mystery Inc. gang to solve the mystery of a horrible Dragon-man Robot that's terrorizing the city. 09:00 TEEN TITANS GO! Repeat WS PG Girl's Night Out / You're Fired Robin, Cyborg, and Beast Boy won’t let Starfire come along on their "Boys' Night Out", feeling she isn't crazy enough for the night ahead. -

European High-End Fiction Series. State of Play and Trends

European high-end fiction series: State of play and trends This report was prepared with the support of the Creative Europe programme of the European Union. If you wish to reproduce tables or graphs contained in this publication, please contact the European Audiovisual Observatory for prior approval. The analysis presented in this publication cannot in any way be considered as representing the point of view of the European Audiovisual Observatory, its members or the Council of Europe. The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, which reflect the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. European high-end fiction series: State of play and trends Gilles Fontaine Marta Jiménez Pumares Table of contents Executive summary .................................................................................................. 1 Scope and methodology .......................................................................................... 5 1. Setting the scene in figures ............................................................................. 8 1.1. The production of high-end fiction series in the European Union .................................................................... 8 1.1.1. The UK is the primary producer of high-end series in Europe ................................................... 10 1.1.2. International co-productions: small but growing .......................................................................... -

View Public Schedule

Schedule Shaun the Sheep Family The 33rd Annual OCT28 - NOV 6 .org 2016 Take the Festival home. Stream 500+ Fest favs on any device with Facets Kids. Contents18 Welcome 3 Tickets & Festival Family Pass 4 Reading the Schedule 5 Workshops 7 Opening Night 11 Saturday, October 29 12 Schedule Grid Pullout 21 Sunday, October 30 19 Weekday Evening 27 Saturday, November 31 33 Sunday, November 1 40 Supporters 45-46 Festival Highlights Teens In Your Dreams 25 Tots & Tykes The Pitch 26 Blue Bicycle 30 Solving Problems All On Our Own 12 Love Hurts 31 Daytrippers 13 Parents... They Mean Well 32 Pat & Mat 19 Whole New Game 42 Molly Monster 20 Me, Myself & I 33 Documentary Features L’ aventure vous attend! 34 Young Wrestlers 25 Depending on How You Look At It 40 Not Without Us 30 Big Kids Halloween Iqbal Farooq And The Secret Recipe 12 Molly Monster 20 Phantom Boy 14, 17, 28, 29, 37, 38 Halloween: Monsters & Mischief 21 Heidi 20 Halloween: Delusions and Illusions 21 Bounders and Bunglers 36 Louis & Luca - The Big Cheese Race 40 Anime & Edgy Anima!ion Tatu and Patu 41 Phantom Boy 14, 17, 28, 29, 37, 38 Help, I Shrunk My Teacher! 41 Animation Masters 16 Edgy Animation: “Way of Giants” 17, 30, 39 Tweens Edgy Animation: Express Yourself” 26, 31 Little Mountain Boy 14 Animation Amuse-Bouches 28 Beauty And The Beast 16 Edgy Animation: One Hell Of A Plan” 31 Abulele 19 Kai 33 Brothers Of The Wind 25 Long Way North 35, 39 Kai 33 Animation A-Team 36 Long Way North 35, 39 Louis & Luca - The Big Cheese Race 40 1 Akouo Connecting Kids and Families to the best Movies from around the world. -

18 Rounded up in County by ED WALSH Tune, Eatontown, and Fair Tie Arresting Teams, Which Vid B

SEEST0RYPAGE2 Rain Expected .. and tonight, Cloudy with FINAL chance of showers tomorrow., Bed Bank, Freehold 1 Long Branch EDITION Moninoiith County's Home Newspaper for 92 Years V0I.-93NO.222 RED BANK N J. THURSDAY. MAY 13, T97I TEN CENTO 18 Rounded Up in County By ED WALSH tune, Eatontown, and Fair Tie arresting teams, which vid B. Kelly, state police.su- A large quantity of heroin SC; Raymond C. Werner, 28, ald L. Cook, 26, 35 Watson FREEHOLD - Eighteen Haven. included 20 state troopers, 33 perihtendent, on the area's bad been confiscated during 523 Sairs Ave.; his brother; Place, Eatontown; Frank people were £ni custody by 8 According to State Police local police officers, and eight drug problem. this morning's raid and other John B. Werner, 21, same ad- Lupinaccia, 25, 31 Chelsea a.m. today as a result of an Sgt. Frank R. Licitra, who men from, "the county prose- "This is a long tedious and merchandise, including three dress; Gary Tawler, 34, 257 Aye.; James Williams, 23, 95 early morning narcotics raid coordinated the raid, under-' cutor's office were briefed by dangerous job, which includes- allegedly stolen color tele- Willow Ave.; James E. Tur- Lippincott Ave.; John W. Wil- conducted by state, county, cover agents had purchased a Sgt Licitra at 5 a.m. in tie. a lot of man hours and mon- vision sets were recovered by pin, 34, 246 Central Ave.; liams, 29,62 Grant Court; Vin- .-and local police. quantity of heroin during the Grand Jury Boom of the Mon- ey," Sgt. -

The Stakes of Holocaust Interpretation and Remembrance in Poland and the United States

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Honors Theses Student Research 2019 On Writing and Righting History: The Stakes of Holocaust Interpretation and Remembrance in Poland and the United States Noa Gutow-Ellis Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses Part of the Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Colby College theses are protected by copyright. They may be viewed or downloaded from this site for the purposes of research and scholarship. Reproduction or distribution for commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the author. Recommended Citation Gutow-Ellis, Noa, "On Writing and Righting History: The Stakes of Holocaust Interpretation and Remembrance in Poland and the United States" (2019). Honors Theses. Paper 917. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses/917 This Honors Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. ON WRITING AND RIGHTING HISTORY: THE STAKES OF HOLOCAUST INTERPRETATION AND REMEMBRANCE IN POLAND AND THE UNITED STATES Noa Gutow-Ellis History Colby College May 2019 Adviser: Dr. Arnout van der Meer Reader: Dr. Raffael Scheck TABLE OF CONTENTS Epigraph ………………………………………………………………………….……………….. 2 Acknowledgments ……………………………………………………………………………..…..3. Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………..….…4 1. Stories of Separate Suffering: Tracing the Historiography of American and Polish Interpretations of the Holocaust …………………………………………………..………..11 2. “The antonym for Auschwitz is justice”: American Jews Encounter Poland ……………. 29 The Beginnings of American Jewish Holocaust Tourism …………….………….. 32 Entering Mainstream America: Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List ...…..…...…… 38 Selling Schindler’s List to the Public ……………………………………………. -

Horses 1-2-3 in Stakes

Horses 1-2-3 in Stakes he following section of The Blood-Horse Stakes Annual for 2008 provides an Talphabetical listing of horses who won or placed in 2008 North American stakes, includ- ing pedigree and stakes performances. The Blood-Horse Stakes Annual for 2008. Copyright © 2009, by Blood-Horse Publications. All Rights Reserved. This publication may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Blood-Horse Publications. Horses 1st, 2nd, 3rd in Stakes Acinonyx (ch f, 2004, Luhuk—Lydia Louise, by A DYNAMITE TIME (b c, 2006, Defrere—Heckuva Southern Halo), 3rd Skipat S, $5,500; Whimscal S Time, by Gilded Time), New Jersey Juvenile S (R), (R), $5,500. $36,000. Horses which finished first, second, or ACK MAGICAL (b g, 2004, Magic Flagship— AFERDS CODE RED (gr/ro g, 2004, Codys Key— third in 2008 North American stakes races Methodical, by Ack Ack), Magic City Classic S (R), Aferds Mistress, by Aferd), Dean Kutz Memorial S $19,250. (R), $6,000; 2nd Bet America S, $1,560. are listed alphabetically. ACOMA (b f, 2005, Empire Maker—Aurora, by Danzig), Affair Lady (dkb/br f, 2001, Ian’s Affair—Ffrappin Force, Stakes winners are in capital letters; bold Dogwood S (gr. III), $66,904; Pin Oak Valley View S by Family Doctor), 3rd Parson Printing and face type indicates winners of black-type (gr. IIIT), $93,000; Mrs. Revere S (gr. IIT), $117,696; Typography S, $600. 2nd Monmouth Oaks (gr. III), $30,000.