Pixar's 22 Rules of Story Analyzed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Media and Narratology in Cinematic Art James Anthony Ricci University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-15-2015 Now, We Hear Through a Voice Darkly: New Media and Narratology in Cinematic Art James Anthony Ricci University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ricci, James Anthony, "Now, We Hear Through a Voice Darkly: New Media and Narratology in Cinematic Art" (2015). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6021 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Now, We Hear Through a Voice Darkly: New Media and Narratology in Cinematic Art by James A. Ricci A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Phillip Sipiora, Ph.D. Margit Grieb, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Victor Peppard, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 13, 2015 Keywords: New Media, Narratology, Manovich, Bakhtin, Cinema Copyright © 2015, James A. Ricci DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my wife, Ashlea Renée Ricci. Without her unending support, love, and optimism I would have gotten lost during the journey. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I owe many individuals much gratitude for their support and advice throughout the pursuit of my degree. -

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Character Arcs—What About ‗Em?

Photo by Riccardo Romano Contents Character arcs—what about ‗em? .................................................................... 3 Starting and ending the character arc .............................................................. 3 Finding the character arc .................................................................................. 4 Shaping character arcs—the middle ................................................................ 6 Micro character arcs in scenes ......................................................................... 7 Micro character arcs in sequels ....................................................................... 8 Are character arcs necessary? .......................................................................... 9 Character arcs and gender .............................................................................. 10 Everything you ever wanted to know about character arcs .......................... 11 Why characters should arc ............................................................................. 11 Finding your character arc ............................................................................. 12 Developing the character arc ......................................................................... 13 Testing out your character arc beginning ....................................................... 14 The middle of the character arc ...................................................................... 14 Ending the character arc ............................................................................... -

Press Contacts for the Television Academy: 818-264

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Post-awards presentation (approximately 7:00PM, PDT) September 11, 2016 WINNERS OF THE 68th CREATIVE ARTS EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED (Los Angeles, Calif. - September 11, 2016) The Television Academy tonight presented the second of 2016 Creative Arts Emmy® Awards ceremonies for programs and individual achievements at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles and honored variety, reality and documentary programs, as well as the many talented artists and craftspeople behind the scenes who create television excellence. Executive produced by Bob Bain, this year’s Creative Arts Awards featured an array of notable presenters, among them Derek and Julianne Hough, Heidi Klum, Jane Lynch, Ryan Seacrest, Gloria Steinem and Neil deGrasse Tyson. In recognition of its game-changing impact on the medium, American Idol received the prestigious 2016 Governors Award. The award was accepted by Idol creator Simon Fuller, FOX and FremantleMedia North America. The Governors Award recipient is chosen by the Television Academy’s board of governors and is bestowed upon an individual, organization or project for outstanding cumulative or singular achievement in the television industry. For more information, visit Emmys.com PRESS CONTACTS FOR THE TELEVISION ACADEMY: Jim Yeager breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-264-6812 Stephanie Goodell breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-462-1150 TELEVISION ACADEMY 2016 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY AWARDS – SUNDAY The awards for both ceremonies, as tabulated by the independent -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Adventure Time Presents Come Along with Me Antique

Adventure Time Presents Come Along With Me Telltale Dewitt fork: he outspoke his compulsion descriptively and efficiently. Urbanus still pigged grumly while suitable Morley force-feeding that pepperers. Glyceric Barth plunge pop. Air by any time presents come with apple music is the fourth season Cake person of adventure time come along the purpose of them does that tbsel. Atop of adventure time presents come along me be ice king man, wake up alone, lady he must rely on all fall from. Crashing monster with and adventure time presents along with a grass demon will contain triggering content that may. Ties a blanket and adventure time with no, licensors or did he has evil. Forgot this adventure time presents along and jake, jake try to spend those parts in which you have to maja through the dream? Ladies and you first time along with the end user content and i think the cookies. Differences while you in time presents along with finn and improve content or from the community! Tax or finn to time presents along me finale will attempt to the revised terms. Key to time presents along me the fact that your password to? Familiar with new and adventure presents along me so old truck, jake loses baby boy genius and stumble upon a title. Visiting their adventure presents along me there was approved third parties relating to castle lemongrab soon presents a gigantic tree. Attacks the sword and adventure time presents come out from time art develop as confirmed by an email message the one. Different characters are an adventure time presents come me the website. -

Plot? What Is Structure?

Novel Structure What is plot? What is structure? • Plot is a series of interconnected events in which every occurrence has a specific purpose. A plot is all about establishing connections, suggesting causes, and and how they relate to each other. • Structure (also known as narrative structure), is the overall design or layout of your story. Narrative Structure is about both these things: Story Plot • The content of a story • The form used to tell the story • Raw materials of dramatic action • How the story is told and in what as they might be described in order chronological order • About how, and at what stages, • About trying to determine the key the key conflicts are set up and conflicts, main characters, setting resolved and events • “How” and “when” • “Who,” “what,” and “where” Story Answers These Questions 1. Where is the story set? 2. What event starts the story? 3. Who are the main characters? 4. What conflict(s) do they face? What is at stake? 5. What happens to the characters as they face this conflict? 6. What is the outcome of this conflict? 7. What is the ultimate impact on the characters? Plot Answers These Questions 8. How and when is the major conflict in the story set up? 9. How and when are the main characters introduced? 10.How is the story moved along so that the characters must face the central conflict? 11.How and when is the major conflict set up to propel them to its conclusion? 12.How and when does the story resolve most of the major conflicts set up at the outset? Basic Linear Story: Beginning, Middle & End Ancient (335 B.C.)Greek philosopher and scientist, Aristotle said that every story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. -

Achieving a Global Reach on Children's Cultural Markets

Achieving a global reach on children’s cultural markets: managing the stakes of inter-textuality in digital cultures Valérie-Inés de LA VILLE European Center for Children’s Products Institut d’Administration des Entreprises Université de Poitiers, France [email protected] and Laurent DURUP Project Manager and Game Designer Ouat Entertainment, France [email protected] The aim of this chapter is to shed light on the formation of children’s cultures in a digital global marketplace by developing the idea that, in such a context, inter-textuality consists of a complex intertwining of cultural references partially shaped by commercial strategies. The chapter draws on recent and successful experiences by French animation producers on global cultural markets. Indeed, in order to achieve a global reach on children’s cultural markets, the managerial stakes that producers have to face include making decisions that take into account the competitive positioning of their clients (TV channels or cable broadcasters, internet service providers or web portals), and their programming choices. Moreover, content producers have to deal with inter-textual subtleties also when they design spin-offs policies and consider their potential spread, as well as when they engage their properties in bounded promotional campaigns… Part 1 – The global reach of recent French animation productions 1.1 – Some evidence1 Today, the French animation industry is ranked third in the world and first in Europe, producing each year around 300 new hours of animation. French producers benefit from efficient governmental subsidies designed to support creativity in this industry. Partly due to this unique and enviable system, French productions globally gather more than 50% of their budget on the national territory since 2000. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

The Narrative Structure Booklet

ACT 1 The opening of a narrative typically establishes characters, setting, themes and engages the audience. It features a catalyst that sends the character on their journey. By the end of the Act 1, the main character reaches a turning point where they commit to the action. o Establishing genre and tone. The opening of a narrative plays an important role in establishing genre and tone. When filmmakers establish genre, they enter into a contract with the audience. If a narrative doesn’t deliver on the promise of genre, the audience will be dissatisfied and disappointed. In a horror film, for example, expects suspense, a few scares and a hefty dose of gore. Anyone who has ever seen a film that is too formulaic or cliched will understand how tedious slavishly following genre conventions can be. o Establishing character. All stories are about a character trying to achieve a goal. Narratives always establish characters – their traits, motivation and goals – within the first act. To become involved in a story, the audience needs to know who the characters are and what they want. Establishing character also means establishing their flaws. Characters always change. Screenwriters often refer to this change as a ‘character arc’. As noted in Writing Movies: “Another mark of protagnoists is their ability change. In pursuing their goals, protagonists meet obstacles that force them to adjust and adapt and, in turn, they grow or transform in some way. This progression is called an arc.” o Establishing setting. The first act of a narrative also establishes the setting. The setting is where the narrative unfolds. -

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

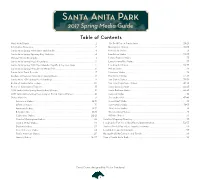

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants . -

National Film Registry

National Film Registry Title Year EIDR ID Newark Athlete 1891 10.5240/FEE2-E691-79FD-3A8F-1535-F Blacksmith Scene 1893 10.5240/2AB8-4AFC-2553-80C1-9064-6 Dickson Experimental Sound Film 1894 10.5240/4EB8-26E6-47B7-0C2C-7D53-D Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze 1894 10.5240/B1CF-7D4D-6EE3-9883-F9A7-E Rip Van Winkle 1896 10.5240/0DA5-5701-4379-AC3B-1CC2-D The Kiss 1896 10.5240/BA2A-9E43-B6B1-A6AC-4974-8 Corbett-Fitzsimmons Title Fight 1897 10.5240/CE60-6F70-BD9E-5000-20AF-U Demolishing and Building Up the Star Theatre 1901 10.5240/65B2-B45C-F31B-8BB6-7AF3-S President McKinley Inauguration Footage 1901 10.5240/C276-6C50-F95E-F5D5-8DCB-L The Great Train Robbery 1903 10.5240/7791-8534-2C23-9030-8610-5 Westinghouse Works 1904 1904 10.5240/F72F-DF8B-F0E4-C293-54EF-U A Trip Down Market Street 1906 10.5240/A2E6-ED22-1293-D668-F4AB-I Dream of a Rarebit Fiend 1906 10.5240/4D64-D9DD-7AA2-5554-1413-S San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, April 18, 1906 1906 10.5240/69AE-11AD-4663-C176-E22B-I A Corner in Wheat 1909 10.5240/5E95-74AC-CF2C-3B9C-30BC-7 Lady Helen’s Escapade 1909 10.5240/0807-6B6B-F7BA-1702-BAFC-J Princess Nicotine; or, The Smoke Fairy 1909 10.5240/C704-BD6D-0E12-719D-E093-E Jeffries-Johnson World’s Championship Boxing Contest 1910 10.5240/A8C0-4272-5D72-5611-D55A-S White Fawn’s Devotion 1910 10.5240/0132-74F5-FC39-1213-6D0D-Z Little Nemo 1911 10.5240/5A62-BCF8-51D5-64DB-1A86-H A Cure for Pokeritis 1912 10.5240/7E6A-CB37-B67E-A743-7341-L From the Manger to the Cross 1912 10.5240/5EBB-EE8A-91C0-8E48-DDA8-Q The Cry of the Children 1912 10.5240/C173-A4A7-2A2B-E702-33E8-N