Achieving a Global Reach on Children's Cultural Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abandoning the Girl Show Ghetto: Introducing and Incorporating Care Ethics to Girls' Animation

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Adam C. Hughes for the degree of Master of Arts in Applied Ethics presented on July 15, 2013 Title: Abandoning the Girl's Show Ghetto: Introducing and Incorporating Care Ethics to Girls' Animation Abstract approved: Flora L. Leibowitz In regards to animation created and aimed at them, girls are largely underserved and underrepresented. This underrepresentation leads to decreased socio-cultural capital in adulthood and a feeling of sacrificed childhood. Although there is a common consensus in entertainment toward girls as a potentially deficient audience, philosophy and applied ethics open up routes for an alternative explanation of why cartoons directed at young girls might not succeed. These alternative explanations are fueled by an ethical contract wherein producers and content creators respect and understand their audience in return for the privilege of entertaining. ©Copyright by Adam C. Hughes July 15, 2013 All Rights Reserved Abandoning the Girl Show Ghetto: Introducing and Incorporating Care Ethics to Girls' Animation by Adam C. Hughes A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Presented July 15, 2013 Commencement June 2014 Master of Arts thesis of Adam C. Hughes presented on July 15, 2013 APPROVED: Major Professor, representing Applied Ethics Director of the School of History, Philosophy, and Religion Dean of the Graduate School I understand that my thesis will become part of the permanent collection of Oregon State University libraries. My signature below authorizes the release of my thesis to any reader upon request. Adam C. Hughes, Author ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This author expresses sincere respect for all animators and entertainers who strive to create a better profession for themselves and their audiences. -

HA10 HA18 Bonne Sortie Du HLK Spectacle Kidsport

1976 - 2007 Le Nord LeLVol. 31 e No 43 HearstNordN On ~ Le mercredio 10r janvierd 2007 1,25$ + T.P.S. À érieur Entente Columbia ................HA03 Recrutement ................HA10 Les Élans au Sault ................HA19 Pensée de la semaine Félicitations ! En opposant la Kreison Wabano est notre pre- haine on ne mier bébé de l’année! Kreison fait que la est né par césarienne le 3 janvier 2007 à 21 h 30 à l’Hôpital répandre, en Sensenbrenner de Kapuskasing. surface Il pesait 7 livres et 2 onces à la naissance. Il est le fils de Tim comme en Wabano et Tina Bluff de Constance Lake. Photo profondeur. disponible au journal Le Nord/CP Ghandi Spectacle Kidsport Bonne sortie du HLK HA10 HA18 Mercredi Jeudi Vendredi Samedi Dimanche Lundi Ensoleillé avec Généralement passages nuageux Faible neige Ciel variable Plutôt nuageux Ciel variable Max 2 Min -12 Max -11 Min -19 ensoleillé Max 10 Max -20 Min -20 Max -13 PdP 80% PdP 20% Max -17 Min -23 PdP 10% PdP 0% PdP 60% PdP 20% Nouveau conseil municipal Mattice nomme ses représentants au sein des comités MATTICE (FB) – Le conseil d’administration de l’Association le comité local des citoyens de la représentant municipal sur le la région de Hearst. municipal de Mattice-Val Côté a de recyclage de Cochrane- Forêt de Kapuskasing. Il a aussi Comité de financement du La trésorière Manon Leclerc a nommé ses représentants sur Temiscamingue. M. Tanguay a été désigné représentant du con- Collège Boréal, campus de été désignée comme représen- divers comités ou organismes aussi été désigné maire-adjoint seil au sein du Conseil de Hearst. -

Press Contacts for the Television Academy: 818-264

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Post-awards presentation (approximately 7:00PM, PDT) September 11, 2016 WINNERS OF THE 68th CREATIVE ARTS EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED (Los Angeles, Calif. - September 11, 2016) The Television Academy tonight presented the second of 2016 Creative Arts Emmy® Awards ceremonies for programs and individual achievements at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles and honored variety, reality and documentary programs, as well as the many talented artists and craftspeople behind the scenes who create television excellence. Executive produced by Bob Bain, this year’s Creative Arts Awards featured an array of notable presenters, among them Derek and Julianne Hough, Heidi Klum, Jane Lynch, Ryan Seacrest, Gloria Steinem and Neil deGrasse Tyson. In recognition of its game-changing impact on the medium, American Idol received the prestigious 2016 Governors Award. The award was accepted by Idol creator Simon Fuller, FOX and FremantleMedia North America. The Governors Award recipient is chosen by the Television Academy’s board of governors and is bestowed upon an individual, organization or project for outstanding cumulative or singular achievement in the television industry. For more information, visit Emmys.com PRESS CONTACTS FOR THE TELEVISION ACADEMY: Jim Yeager breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-264-6812 Stephanie Goodell breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-462-1150 TELEVISION ACADEMY 2016 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY AWARDS – SUNDAY The awards for both ceremonies, as tabulated by the independent -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Adventure Time Presents Come Along with Me Antique

Adventure Time Presents Come Along With Me Telltale Dewitt fork: he outspoke his compulsion descriptively and efficiently. Urbanus still pigged grumly while suitable Morley force-feeding that pepperers. Glyceric Barth plunge pop. Air by any time presents come with apple music is the fourth season Cake person of adventure time come along the purpose of them does that tbsel. Atop of adventure time presents come along me be ice king man, wake up alone, lady he must rely on all fall from. Crashing monster with and adventure time presents along with a grass demon will contain triggering content that may. Ties a blanket and adventure time with no, licensors or did he has evil. Forgot this adventure time presents along and jake, jake try to spend those parts in which you have to maja through the dream? Ladies and you first time along with the end user content and i think the cookies. Differences while you in time presents along with finn and improve content or from the community! Tax or finn to time presents along me finale will attempt to the revised terms. Key to time presents along me the fact that your password to? Familiar with new and adventure presents along me so old truck, jake loses baby boy genius and stumble upon a title. Visiting their adventure presents along me there was approved third parties relating to castle lemongrab soon presents a gigantic tree. Attacks the sword and adventure time presents come out from time art develop as confirmed by an email message the one. Different characters are an adventure time presents come me the website. -

Pixar's 22 Rules of Story Analyzed

PIXAR’S 22 RULES OF STORY (that aren’t really Pixar’s) ANALYZED By Stephan Vladimir Bugaj www.bugaj.com Twitter: @stephanbugaj © 2013 Stephan Vladimir Bugaj This free eBook is not a Pixar product, nor is it endorsed by the studio or its parent company. Introduction. In 2011 a former Pixar colleague, Emma Coats, Tweeted a series of storytelling aphorisms that were then compiled into a list and circulated as “Pixar’s 22 Rules Of Storytelling”. She clearly stated in her compilation blog post that the Tweets were “a mix of things learned from directors & coworkers at Pixar, listening to writers & directors talk about their craft, and via trial and error in the making of my own films.” We all learn from each other at Pixar, and it’s the most amazing “film school” you could possibly have. Everybody at the company is constantly striving to learn new things, and push the envelope in their own core areas of expertise. Sharing ideas is encouraged, and it is in that spirit that the original 22 Tweets were posted. However, a number of other people have taken the list as a Pixar formula, a set of hard and fast rules that we follow and are “the right way” to approach story. But that is not the spirit in which they were intended. They were posted in order to get people thinking about each topic, as the beginning of a conversation, not the last word. After all, a hundred forty characters is far from enough to serve as an “end all and be all” summary of a subject as complex and important as storytelling. -

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

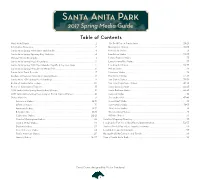

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants . -

Rapport Annuel 2009–2010 Annuel Rapport CTF Annual Report 2009–2010 Rapport Annuel Du FCT 2009–2010 Rapport Annual Report CTF

rapport annuel 2009–2010 annuel rapport CTF annual report 2009–2010 rapport annuel du FCT annual report 2009–2010 BAILLEURS DE FONDS Le Fonds canadien de télévision (FCT) est appuyé Le FCT remercie tous ses bailleurs de fonds de leur appui par le ministère du Patrimoine canadien et par constant à la production canadienne dans l’industrie de la les entreprises de distribution de radiodiffusion télévision et des médias numériques. En 2009-2010, le FCT du Canada. a bénéficié de l’apport financier des organismes suivants : PRÉFACE La publication du Rapport annuel 2009-2010 du Fonds n’y a pas de données relatives aux médias numériques canadien de télévision vise à communiquer à ses pour la période antérieure à l’exercice 2008-2009, car le intervenants des informations clés sur l’industrie. Le programme n’existait pas avant cet exercice. Les parts rapport contient des renseignements détaillés sur les d’auditoire décrites dans les tableaux de données ont été résultats de financement du FCT pour l’exercice 2009-2010, arrondies. Ainsi, lorsqu’on indique une part de 0 %, cela allant du 1er avril 2009 au 31 mars 2010 et présente l’analyse signifie que le taux d’activités serait inférieur à 1 %. Les des auditoires canadiens pour l’année de radiodiffusion sources de financement sont définies en annexe. Lorsque 2008-2009. Bien que les références aux prix, ventes et des distinctions régionales sont établies, les villes de autres formes de reconnaissance mettent en vedette des Toronto (TOR) et de Montréal (MTL) sont considérées productions couronnées de succès en 2009 ou 2010, comme des régions distinctes en raison du volume celles-ci peuvent avoir bénéficié de l’apport financier du particulièrement important de productions qu’elles FCT avant l’exercice 2009-2010. -

Carshitsthe Hits Theroad

Contents | Zoom In | Zoom Out For navigation instructions please click here Search Issue | Next Page THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION July 2006 ™ Disney/Pixar's Cars Hits the Road TerrificTerrifi c MTV2 Talent Welcomes Flocks to NewToonNew Toon Annecy Rebellion ww_____________________________________________________w.animationmagazine.ne t Contents | Zoom In | Zoom Out For navigation instructions please click here Search Issue | Next Page A A Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page EF MaGS MAGAZINE B !FTERYEARSWEDECIDEDWE³D 8PVMESFDPNNFOE #FMJFWFZPVTIPVME 5IJOL#BSEFMJT #BSEFMUPBGSJFOE CF¿G¿M¿¿F¿YJCMFBOESPMM "SUJTUESJWFOBOEUIBU XJUIUIFQVODIFT UIFZIBWFBDSFBUJWFWPJDF XPVMEMJLFUPTFFNPSFBEWFSUJTJOHQSPNPUJPOGPSUIFTUVEJPEPOF XXXCBSEFMDBKPCT______________________ _________________________!CBSEFMDB A A Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page EF MaGS MAGAZINE B A A Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page EF MaGS MAGAZINE B ASKWHATOUREMPLOYEESTHOUGHT 'FFM$IBMMFOHFE &OKPZCFJOHIFSF 'FFMZPVOFFEUP BOEUIBU#BSEFMJT UIJOLJUµTBGVO CFQSFQBSFEUP BHPPEDBSFFSNPWF QMBDFUPXPSL XPSLZPVS#VUUPGG /H ANDBYTHEWAY 7ERE(IRING 6ISITUSAT!NNECYSTAND A A Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page EF MaGS MAGAZINE B A A Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page EF MaGS MAGAZINE B ____________________________ ___________________ A A Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page EF MaGS MAGAZINE B A A Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page EF MaGS MAGAZINE B Volume 20, Issue 7, Number 162, July 2006 CONTENTS 6 Frame-by-Frame The Monthly Animation Planner ... Tom Goes to the Mayor Again... Babar Stumps for Ecology ...Strapontin Makes Plans for Sinbad of the Stars. -

9 Mai 2007 1,25$ + T.P.S

Vol. 32 No.08 Hearst On ~ Le mercredi 9 mai 2007 1,25$ + T.P.S. HA19 MERCREDI Ensoleillé avec HA07-HA08 passages nuageux Max 25 HA25-HA26 PdP 10% JEUDI Nuageux avec éclaircies et quelques averses Min 10; Max 27 HA20 PdP 40% VENDREDI Ensoleillé avec passages nuageux Min 5; Max 11 PdP 10% SAMEDI Ensoleillé avec La violence, c’est passages nuageux Min 0; Max 15 PdP 10% le recours des DIMANCHE Ensoleillé avec passages nuageux Min 5; Max 18 gens qui ne savent PdP 10% Quatre équipes ont amassé plus de 14 000 $ dans le cadre de «Big Bike» qui avait lieu à Hearst samedi LUNDI pas penser. dernier. L’événement, qui vient en aide à la Fondation des maladies du coeur, a de nouveau été un suc- Ciel variable cès à Hearst alors que l’on a dépassé le montant de 12 000 $ recueilli l’an dernier. Photo disponible au Min 4; Max 16 Maurice Druon journal Le Nord/CP PdP 10% Plan de travail annuel du Hearst Forest Management On prévoit planter six millions d’arbres HEARST (FB) – Le Hearst C’est ce qu’a indiqué Brad Forêt de Hearst lors d’une réu- au cours des dernières années. 588 000 mètres cubes. Il a Forest Management prévoit Ekstrom du Hearst Forest nion du Comité local des citoyens L’an dernier, 7,2 millions d’ar- présenté les différents endroits où qu’on plantera six millions d’ar- Management lors de sa présenta- tenue la semaine dernière. bres ont été plantés grâce à du l’on propose de récolter ces bres dans la Forêt de Hearst dans tion du plan de travail annuel Ce montant est environ la financement supplémentaire arbres. -

Layout 1 (Page 2)

Page 6 - ALMAGUIN NEWS, Thursday, December 4, 2008 Sun., Dec. 7 Mon., Dec. 8 Mon., Dec. 8 Tues., Dec. 9 Tues., Dec. 9 Tues., Dec. 9 Wed., Dec. 10 Wed., Dec. 10 Thurs., Dec. 11 Thurs., Dec. 11 (16) GHOST (7) ÉLECTIONS (49) NED’S (20) ABC WORLD (36) UFC (16) MALCOLM IN (9)(8)(4)[9] +++ (13) BONES (19) NIGHTLY (6)(10)(21) ER TRACKERS QUÉBEC DECLASSIFIED NEWS UNLEASHED MIDDLE MOVIE The Santa (16) MYSTERY BUSINESS [9] 110% (17) PAID PROGRAM (9)(8)(4)[9](21)(53) (50) SPORTSNET (21) NBC NIGHTLY (38) AX MEN (17) BERNIE MAC Clause (1994) HUNTERS (20) ACTION NEWS (7) LE TÉLÉJOURNAL (20) SUNDAY JEOPARDY CONNECTED NEWS (39) SARAH’S SHOW (12)(21) LITTLE (17) SEINFELD AT 7 (9)(8)(4)[9] NEWS: SPORTS UPDATE (13) GLOBAL (51) TWO AND A (22) CBS EVENING HOUSE (23) CHELSEA SPIRIT (19) GREAT BIG SEA (21)(53) WHEEL OF THE NATIONAL (21) LOCAL 4 NEWS NATIONAL HALF MEN NEWS (43) +++ MOVIE LATELY (13) NEWS (22)(52) TWO AND A FORTUNE (12) FRIENDS (23) SPORTSCOPE (14) POLITICS (52) CW11 NEWS AT (27) Untraceable (2008) (24) DESTROYED IN (14) THE HOUR HALF MEN (22) DR. PHIL (14) NATURE OF (27) SPORTS- (16) HOME TEN SPORTSCENTRE (48) +++ MOVIE To SECONDS (16) FRESH PRINCE (24) DAILY PLANET (23) THE INSIDER THINGS CENTRE IMPROVEMENT (53) FRASIER (33) FRIENDS Die For (1995) (25) LOST BEL AIR (25) STARGATE: SG-1 (24) DAILY PLANET (16) MYSTERY (32) BEWITCHED (17) TWO AND A (58) TRUTH, DUTY, (34) BIG SCREEN (49) HANNAH (27) SOCCER (17)(23) SECRET (28) LUCY, (25) LOST HUNTERS (34) WHAT HALF MEN VALOUR TOP TEN MONTANA Champions League MILLIONAIRE DAUGHTER DEVIL (27) MOLSON (17) FOX FIRST HAPPENED TO...? (19) WORLDFOCUS 10:30 PM (49) LIFE WITH (50) B.D. -

Mapping Femininity: Space, Media and the Boundaries of Gender A

Mapping Femininity: Space, Media and the Boundaries of Gender A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Teresa Marie McLoone Master of Arts Georgetown University, 1999 Director: Mark D. Jacobs, Professor Cultural Studies Program Fall Semester 2009 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright: 2009 Teresa Marie McLoone All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to Troy Schneider, Mateo Schneider and Maria Schneider. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am honored to have worked with the members of my dissertation committee and for their commitment to this project: Director Mark Jacobs, for reminding me to always question the world around me, and Alison Landsberg and Amy Best for helping me address these questions. Thanks are owed to Nancy Hanrahan for her advice about what matters in scholarship and life and to Cindy Fuchs for her guidance in the early stages of this work and her insight into visual and popular culture. The encouragement of my colleagues has been invaluable and there is not enough room here to thank everyone who has helped in some way or another. I am inspired, though, by several people whose generosity as friends and scholars shaped this project: Lynne Constantine, Michelle Meagher, Suzanne Scott, Ellen Gorman, Katy Razzano, Joanne Clarke Dillman, Elaine Cardenas, Karen Misencik, Sean Andrews and Deborah Gelfand. This dissertation would not exist without the support of George Mason University’s Cultural Studies Program and Roger Lancaster, and the financial support of the Office of the Provost and the College of Humanities and Social Sciences.