Supplemental Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Requirements, Design and Applications to Semantic Integration and Knowledge Discovery

Practical Ontologies: Requirements, Design and Applications to Semantic Integration and Knowledge Discovery by Daniela Rosu A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Computer Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Daniela Rosu 2013 Practical Ontologies: Requirements, Design and Applications to Semantic Integration and Knowledge Discovery Daniela Rosu Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Computer Science University of Toronto 2013 Abstract Due to their role in describing the semantics of information, knowledge representations, from formal ontologies to informal representations such as folksonomies, are becoming increasingly important in facilitating the exchange of information, as well as the semantic integration of information systems and knowledge discovery in a large number of areas, from e-commerce to bioinformatics. In this thesis we present several studies related to the development and application of knowledge representations, in the form of practical ontologies. In Chapter 2, we examine representational challenges and requirements for describing practical domain knowledge. We present representational requirements we collected by surveying current and potential ontology users, discuss current approaches to codifying knowledge and give formal representation solutions to some of the issues we identified. In Chapter 3 we introduce a practical ontology for representing data exchanges, discuss its relationship with existing standards and its role in facilitating the interoperability between information producing and consuming services. ii We also consider the problem of assessing similarity between ontological concepts and propose three novel measures of similarity, detailed in Chapter 4. Two of our proposals estimate semantic similarity between concepts in the same ontology, while the third measures similarity between concepts belonging to different ontologies. -

Hidden Meaning

FEATURES Microdata and Microformats Kit Sen Chin, 123RF.com Chin, Sen Kit Working with microformats and microdata Hidden Meaning Programs aren’t as smart as humans when it comes to interpreting the meaning of web information. If you want to maximize your search rank, you might want to dress up your HTML documents with microformats and microdata. By Andreas Möller TML lets you mark up sections formats and microdata into your own source code for the website shown in of text as headings, body text, programs. Figure 1 – an HTML5 document with a hyperlinks, and other web page business card. The Heading text block is H elements. However, these defi- Microformats marked up with the element h1. The text nitions have nothing to do with the HTML was originally designed for hu- for the business card is surrounded by meaning of the data: Does the text refer mans to read, but with the explosive the div container element, and <br/> in- to a person, an organization, a product, growth of the web, programs such as troduces a line break. or an event? Microformats [1] and their search engines also process HTML data. It is easy for a human reader to see successor, microdata [2] make the mean- What do programs that read HTML data that the data shown in Figure 1 repre- ing a bit more clear by pointing to busi- typically find? Listing 1 shows the HTML sents a business card – even if the text is ness cards, product descriptions, offers, and event data in a machine-readable LISTING 1: HTML5 Document with Business Card way. -

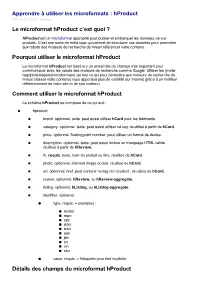

Le Microformat Hproduct C'est Quoi ? Pourquoi Utiliser Le Microformat

Apprendre à utiliser les microformats : hProduct 2017-02-21 23:02:01 Nicolaseo Le microformat hProduct c’est quoi ? hProduct est un microformat approprié pour publier et embarquer les données de vos produits. C’est une sorte de méta tags qui permet de structurer vos données pour permettre aux robots des moteurs de recherche de mieux référencer votre contenu. Pourquoi utiliser le microformat hProduct Le microformat hProduct est basé sur un ensemble de champs très important pour communiquer avec les robots des moteurs de recherche comme Google. Utiliser les {meta- tags|richsnippets|microformats} (et tout ce qui peut permettre aux moteurs de recherche de mieux classer votre contenu) vous apportera plus de visibilité sur internet grâce à un meilleur référencement de votre site et de son contenu. Comment utiliser le microformat hProduct Le schéma hProduct se compose de ce qui suit : hproduct brand. optionnel. texte. peut aussi utiliser hCard pour les fabricants. category. optionnel. texte. peut aussi utiliser rel-tag. ré-utilisé à partir de hCard. price. optionnel. floating point number. peut utiliser un format de devise. description. optionnel. texte. peut aussi inclure un marquage HTML valide. réutilisé à partir de hReview. fn. requis. texte. nom du produit ou titre. réutilisé de hCard. photo. optionnel. élément image ou lien. réutilisé de hCard. url. optionnel. href. peut contenir rel-tag rel=’product’. ré-utilisé de hCard. review. optionnel. hReview, ou hReview-aggregate. listing. optionnel. hListing, ou hListing-aggregate. identifier. optionnel. type. requis. – exemples : model mpn upc isbn issn ean jan sn vin sku value. requis. – l’étiquette peut être implicite. Détails des champs du microformat hProduct Les noms de classe category, fn, photo, url sont réutilisés à partir de hCard. -

Where Is the Semantic Web? – an Overview of the Use of Embeddable Semantics in Austria

Where Is The Semantic Web? – An Overview of the Use of Embeddable Semantics in Austria Wilhelm Loibl Institute for Service Marketing and Tourism Vienna University of Economics and Business, Austria [email protected] Abstract Improving the results of search engines and enabling new online applications are two of the main aims of the Semantic Web. For a machine to be able to read and interpret semantic information, this content has to be offered online first. With several technologies available the question arises which one to use. Those who want to build the software necessary to interpret the offered data have to know what information is available and in which format. In order to answer these questions, the author analysed the business websites of different Austrian industry sectors as to what semantic information is embedded. Preliminary results show that, although overall usage numbers are still small, certain differences between individual sectors exist. Keywords: semantic web, RDFa, microformats, Austria, industry sectors 1 Introduction As tourism is a very information-intense industry (Werthner & Klein, 1999), especially novel users resort to well-known generic search engines like Google to find travel related information (Mitsche, 2005). Often, these machines do not provide satisfactory search results as their algorithms match a user’s query against the (weighted) terms found in online documents (Berry and Browne, 1999). One solution to this problem lies in “Semantic Searches” (Maedche & Staab, 2002). In order for them to work, web resources must first be annotated with additional metadata describing the content (Davies, Studer & Warren., 2006). Therefore, anyone who wants to provide data online must decide on which technology to use. -

Data Models for Home Services

__________________________________________PROCEEDING OF THE 13TH CONFERENCE OF FRUCT ASSOCIATION Data Models for Home Services Vadym Kramar, Markku Korhonen, Yury Sergeev Oulu University of Applied Sciences, School of Engineering Raahe, Finland {vadym.kramar, markku.korhonen, yury.sergeev}@oamk.fi Abstract An ultimate penetration of communication technologies allowing web access has enriched a conception of smart homes with new paradigms of home services. Modern home services range far beyond such notions as Home Automation or Use of Internet. The services expose their ubiquitous nature by being integrated into smart environments, and provisioned through a variety of end-user devices. Computational intelligence require a use of knowledge technologies, and within a given domain, such requirement as a compliance with modern web architecture is essential. This is where Semantic Web technologies excel. A given work presents an overview of important terms, vocabularies, and data models that may be utilised in data and knowledge engineering with respect to home services. Index Terms: Context, Data engineering, Data models, Knowledge engineering, Semantic Web, Smart homes, Ubiquitous computing. I. INTRODUCTION In recent years, a use of Semantic Web technologies to build a giant information space has shown certain benefits. Rapid development of Web 3.0 and a use of its principle in web applications is the best evidence of such benefits. A traditional database design in still and will be widely used in web applications. One of the most important reason for that is a vast number of databases developed over years and used in a variety of applications varying from simple web services to enterprise portals. In accordance to Forrester Research though a growing number of document, or knowledge bases, such as NoSQL is not a hype anymore [1]. -

Microformats, Metadata

Microformats, Metadata April 29, 2013 1 Introduction 1.1 Content • What are microformats? • Why to use microformats? • How to replace microformats? • Advantages of microformats to own markup. • Disadvantages of microformats.. • Common used microformats • Microformats design patterns. • Resources on microformats. 1.2 What are microformats? • The way how to add simple markup into human readable information to allow computer processing. { acquiring data from documents { indexing { searching { storing { cross-referencing • Microformats are elements of a semantic markup using a plain old semantic (X)HTML (POSH) { Why has been the HTML designed at CERN (Conseil Europ´eenpour la Recherche Nucl´eaire(http://dg-rpc.web.cern.ch/dg-rpc/Scale. html)) v in the year 1991? 1 1.3 Example of Microformat <ol class='xoxo'> <li>Prvn´ıbod <ol> <li>Podbod a</li> <li>Podbod b</li> </ol> </li> <li>Druh´ybod <ol compact="compact"> <li>Podbod c</li> <li>Podbod d</li> </ol> </li> </ol> 1.4 Why to use microformats? Microformats combines some trends: • next logical step in web-design and information architecture progress • the manner how can people and organisations publish semantically rich content without dependency on centralized services • "agreement", that the traditional meta data either failed or their adoption took too long, so there has been a need of a different solution. { microformats use the meta data. :-) • Use of (X)HTML for data. 1.5 How can be microformats replaced? (1) • Including data in own formating in a different namespace { XHTML + Voice Profile (http://www.voicexml.org/specs/multimodal/ x+v/12/) { (X)HTML + SVG { XLink { XHTML+RDF { ... 1.6 How can be microformats replaced? (2) • Advantages: { easy visualisation (direct support in browsers, using CSS for exam- ple), { independent on centralized services. -

An Extensible Discovery Service for Smart Things

An Extensible Discovery Service for Smart Things Simon Mayer Dominique Guinard Inst. for Pervasive Computing Inst. for Pervasive Computing ETH Zurich ETH Zurich Zurich, Switzerland Zurich, Switzerland [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT that, for these, we require a mechanism that allows machines We present DiscoWoT, a semantic discovery service for Web- to discover them and understand their capabilities in order enabled smart things. The service is based on the applica- to enable automatic usage by software applications. Possi- tion of multiple Discovery Strategies to a Web resource's bilities that would be enabled by machine-understandable representation, where arbitrary users can create and update semantic descriptions for smart things range from on-the- strategies at runtime using DiscoWoT's RESTful interface. fly user interface creation based on the specific capabilities Its goal is to provide a future-proof mechanism for enabling of the accessed device to enabling machines to discover re- both, human users and machines, to semantically discover quired services themselves or support users in finding ser- functionality provided by Web-enabled devices. Ultimately, vices within densely populated smart environments. The it aims to allow for the facilitated discovery, selection, and basis for such applications is a generic mechanism that al- utilization of smart things. DiscoWoT incorporates a trans- lows smart devices to provide semantic descriptions of the parent mechanism for deferring resource discovery to exter- services they offer. nal handlers and can thus interact with other services within The problem of describing resources on the Web is not discovery service federations. It may be accessed by arbi- inherent only to smart things, but rather is a general prob- trary users for ad hoc discovery of functionality offered by lem of providing service specifications that has been worked Web resources or incorporated into infrastructures for Web- on mainly in the Semantic Web domain. -

Open and Linked Data

Presentation Topic 11: Open and linked data Group K: Giles Howard Jacob Kittley-Davies S. Mahmoud Miri Velizar Velkov Vlad Velici Henry Wilkes Marcus Ojerinde-Ardalla Tutor: Tim Chown Jacob Kittley- Marcus Mahmoud Miri Henry Wilkes Davies Ojerinde-Ardalla Velizar Velkov Vlad Velici Giles Howard What is Linked Open Data? Introduction ● Linked and Open Data -Two related concepts that are increasingly important in our data centric society. ● Our aim of this presentation is to explain what Open data and Linked Data are, and examine their implementations. ● Also, we will examine arguments for and against open data, and put our own argument forward for it. Definitions (Open Data) ● “Open data is data that can be freely used, reused and redistributed by anyone - subject only, at most, to the requirement to attribute and sharealike.” [1] ● Open data is not a specific implementation or method of accessing data – instead, it is an idea of exactly how it should be used and redistributed. Definitions (Linked Data) ● "The Semantic Web isn't just about putting data on the web. It is about making links, so that a person or machine can explore the web of data. With linked data, when you have some of it, you can find other, related, data. "[2] ● Linked Data is a specific implementation of data, which aims to make it more useful by making it easier for a user to quickly access more relevant data. Background ● Open Data - A general movement towards greater and easier data access, important for academic study and scientific research (Mertonian science) ● -

D2.4 Weblog Spider Prototype and Associated Methodology

SEVENTH FRAMEWORK PROGRAMME FP7-ICT-2009-6 BlogForever Grant agreement no.: 269963 BlogForever: D2.4 Weblog spider prototype and associated methodology Editor: M. Rynning Revision: First version Dissemination Level: Public Author(s): M. Rynning, V. Banos, K. Stepanyan, M. Joy, M. Gulliksen Due date of deliverable: 30th November 2011 Actual submission date: 30th November 2011 Start date of project: 01 March 2011 Duration: 30 months Lead Beneficiary name: CyberWatcher Abstract: This document presents potential solutions and technologies for monitoring, capturing and extracting data from weblogs. Additionally, the selected weblog spider prototype and associated methodologies are analysed. D2.2 Report: Weblog Spider Prototype and Associated Methodology 30 November 2011 Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Seventh Framework Programme (2007-2013) The BlogForever Consortium consists of: Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTH) Greece European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) Switzerland University of Glasgow (UG) UK The University of Warwick (UW) UK University of London (UL) UK Technische Universitat Berlin (TUB) Germany Cyberwatcher Norway SRDC Yazilim Arastrirma ve Gelistrirme ve Danismanlik Ticaret Limited Sirketi (SRDC) Turkey Tero Ltd (Tero) Greece Mokono GMBH Germany Phaistos SA (Phaistos) Greece Altec Software Development S.A. (Altec) Greece BlogForever Consortium Page 2 of 71 D2.2 Report: Weblog Spider Prototype and Associated Methodology 30 November 2011 History Version Date Modification reason Modified -

Novel Approaches to Metadata … Improving the Web

1 Novel approaches to metadata … improving the Web Aarhus12/JBoye Aarhus, Denmark 2012-11-08 Olle Olsson World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) Swedish Institute of Computer Science (SICS) Novel Metadata Approaches 1/31 Olle Olsson 2 Contents ● What do we mean by metadata and semantics? ● Enriched content for automated processing ● What are “light-weight” approaches? ● Technologies ● How they work ● Are these things really used? ● Some statistics ● “What's in it for me?” ● Examples ● So what is the conclusion? ● !!! Novel Metadata Approaches 2/31 Olle Olsson file:///C:/Documents%20and%20Settings/olleo/Skrivbord/G-processes/w3c/demos/%C3%ADndex.html 3 What do we mean by metadata and semantics? Novel Metadata Approaches 3/31 Olle Olsson 4 Web, metadata, semantics ● Web content ● Text, graphics, sound, …. ● What web content means ● Semantics ● Semantical annotations ● Metadata: “what category?” Novel Metadata Approaches 4/31 Olle Olsson 5 Web, metadata, semantics ● Web content ● Text, graphics, sound, …. ● What web content means ● Semantics ● Semantical annotations ● Metadata: “what category?” Tree Shirt Cat Novel Metadata Approaches 5/31 Olle Olsson 6 Purpose of Metadata / Semantics ● Be explicit about how to understand content ● Vocabulary ● Terminology ● Terms identify categories ● Not visible (not part of content) ● Used by mechanisms / tools / software ● Compare: what the web browser does ● Terms identify structure and presentation ● Thesis: A better web by metadata Novel Metadata Approaches 6/31 Olle Olsson 7 When not using semantic annotations -

Agritourism Farms-Evaluation of Their Websites Quality and Web

Agris on-line Papers in Economics and Informatics Volume V Number 1, 2013 Agritourism Farms - Evaluation of Their Websites Quality and Web 2.0 Z. Havlíček, V. Lohr, M. Šmejkalová, J. Grosz, P. Benda Faculty of Economics and management, Czech University of Life Sciences in Prague, Czech Republic Anotace Na základě porovnání výsledků z dotazníkových šetření z let 2009 a 2012 bylo zjištěno, že kvalita www prezentací agroturistických farem se téměř nemění. Kvalita stránek u stejných farem je statisticky vyšší pouze u kritéria “Obsah – struktura” www stránek. Lze usuzovat, že v roce 2012 farmáři věnovali větší pozornost struktuře informací, které prezentují na vlastních stránkách. Farmy, které mají vlastní doménové jméno, vykazují statisticky významně vyšší kvalitu www prezentací. Obecně lze říci, že prezentace agroturistických farem málo využívají nové přístupy v internetových technologiích. Proto byl navržen postup jak inovovat méně kvalitní www prezentace pomocí WCMS WordPress. Je doporučováno více využívat technologie Web 2.0, například pomocí mashup technologií integrovat do webových prezentací související informační zdroje (odkazy na sociální sítě, propojení s počasím nebo zdrojem RSS v daném regionu). Klíčová slova Agroturistika, kvalita website, SEO, Web 2.0, WordPress. Abstract Based on surveys carried out in 2009 and 2012 it can be suggested that the web presentations of agritourism farms are virtually unchanged. The quality of the web pages for the same farms is statistically higher only for the criterion of “Content – structure” of websites. It can be assumed that in 2012 farmers devoted more attention to the structure of information that is presented on their own websites. Farms that have their own domain name show statistically significantly higher quality websites. -

Semantic Web (An Electronic Commerce Perspective)

Concept Technological Overview Applications Summary The Semantic Web, How Does It Work? A Technological Overview & Applications to Electronic Commerce Stephen Balaban EECS 547 2011-01-31 . Stephen Balaban HDIW: The Semantic Web Concept Technological Overview Applications Summary . Table of Contents . ..1 Conceptual Overview In One Sentence The Concept Linked Data E-Commerce Context . ..2 Technological Overview Unifirm Resource Idenifiers (URIs) Resource Description Framework (RDF) Web Ontology Language (OWL) SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language (SPARQL) . ..3 Applications To Electronic Commerce RDFa & Microformats GoodRelations: Electronic Commerce Ontology Microformats RDFa + gr or hProduct . ..4 Summary The Future of the Semantic Web . Stephen Balaban HDIW: The Semantic Web Machine readible Comprised of Resources Resources connected with links Concept In One Sentence Technological Overview The Concept Applications Linked Data Summary E-Commerce . In One Sentence The Semantic Web is a web of data. Stephen Balaban HDIW: The Semantic Web Concept In One Sentence Technological Overview The Concept Applications Linked Data Summary E-Commerce . In One Sentence The Semantic Web is a web of data. Machine readible Comprised of Resources Resources connected with links . Stephen Balaban HDIW: The Semantic Web Concept In One Sentence Technological Overview The Concept Applications Linked Data Summary E-Commerce . The Concept \I have a dream for the Web [in which computers] become capable of analyzing all the data on the Web the content, links, and transactions between people and computers. A Semantic Web, which should make this possible, has yet to emerge, but when it does, the day-to-day mechanisms of trade, bureaucracy and our daily lives will be handled by machines talking to machines.