TV Guidelines.2.Pub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015/2016 WGSA Council V

2015/2016 WGSA Council v Chairperson - Theoline Maphutha THEOLINE MAPHUTHA CHAIRPERSON Theoline Maphutha is a self-employed writer with over five years’ experience in the film and television industry. Before pursuing a career as a writer, she studied and worked in the information and communications technology (ICT) industry for almost 10 years as a support administrator, systems implementer, and project manager. Although skilled in lifestyle/magazine program writing, she’s a published poet, lyricist, and blogger, passionate about kaizen, constant self-improvement. Contribution is one of her highest values (ever since she was a Brownie in the girl scouts). Her life’s goal is to empower people to follow their purpose using the knowledge, experience, and resources available to her. Theoline is an independent soul with nimble flexibility, and a deliberate, succinct style of communication, who delivers autonomously creative ideas and solutions. Vice Chair - Peter Goldsmid PETER GOLDSMID LEGAL SERVICES Writer-director-producer Peter Goldsmid has a background in legal philosophy and politics and a keen interest in the interface between morality, justice, crime, social issues – and drama. This would his final year on Council where, if elected, he would continue to giving advice to writers in their dealings with producers. This includes advising on legal issues (such as contracts), helping writers access professional legal help if necessary, and mediating in disputes. Having worked both as producer and writer for hire, he has a balanced perspective on the issues that affect writers and brings this to bear in his contributions to Council. He is currently nominated for a 2015 writing SAFTA (as part of the “Traffic” writing team) and a Muse Award for documentary writing on Dance up from the street. -

TV News, Reporting and Production MCM 516 Table of Contents Page No

TV News Reporting and Production – MCM 516 VU TV News, reporting and Production MCM 516 Table of Contents Page No. Lesson 1 Creativity and idea generation for television 3 Lesson 2 Pre-requisites of a Creative Producer/Director 7 Lesson 3 Refining an idea for Production 10 Lesson 4 Concept Development 14 Lesson 5 Research and reviews 16 Lesson 6 Script Writing 18 Lesson 7 Pre-production phase 21 Lesson 8 Selection of required Content and talent 25 Lesson 9 Programme planning 29 Lesson 10 Production phase 35 Lesson 11 Camera Work 38 Lesson 12 Light and Audio 43 Lesson 13 Day of Recording/Production 52 Lesson 14 Linear editing and NLE 61 Lesson 15 Mixing and Uses of effects 64 Lesson 16 Selection of the News 69 Lesson 17 Writing of the News 72 Lesson 18 Editing of the News 75 Lesson 19 Compilation of News Bulletin 77 Lesson 20 Presentation of News Bulletin 80 Lesson 21 Making Special Bulletins 82 Lesson 22 Technical Codes, Terminology, and Production Grammar 84 Lesson 23 Types of TV Production 89 Lesson 24 Drama and Documentary 91 Lesson 25 Sources of TV News 93 Lesson 26 Functions of a Reporter 97 Lesson 27 Beats of Reporting 98 Lesson 28 Structure of News Department 99 Lesson 29 Electronic Field Production 101 Lesson 30 Live Transmissions 103 Lesson 31 Qualities of a news producer 108 Lesson 32 Duties of a news producer 111 Lesson 33 Assignment/News Editor 112 Lesson 34 Shooting a News film 114 Lesson 35 Preparation of special reports 117 Lesson 36 Interviews, vox pops and public opinions 121 Lesson 37 Back Ground voice and voice over -

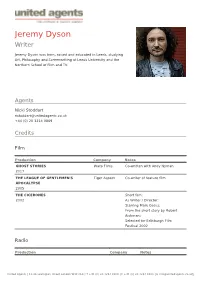

Jeremy Dyson Writer

Jeremy Dyson Writer Jeremy Dyson was born, raised and educated in Leeds, studying Art, Philosophy and Screenwriting at Leeds University and the Northern School of Film and TV. Agents Nicki Stoddart [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0869 Credits Film Production Company Notes GHOST STORIES Warp Films Co-written with Andy Nyman 2017 THE LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN'S Tiger Aspect Co-writer of feature film APOCALYPSE 2005 THE CICERONES Short film; 2002 As Writer / Director; Starring Mark Gatiss; From the short story by Robert Aickman; Selected for Edinburgh Film Festival 2002 Radio Production Company Notes United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] THE UNSETTLED DUST: THE STRANGE STORIES BBC Radio 4 OF ROBERT AICKMAN 2011 RINGING THE CHANGES BBC Radio 4 Co-written with Mark 2000 Gatiss Adapted from the short story by Robert Aickman ON THE TOWN WITH THE LEAGUE OF BBC Radio 4 Co-writer GENTLEMEN Sony Silver Award 1997 Television Production Company Notes THE LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN'S BBC2 ANNIVERSARY SPECIALS 2017 TRACEY ULLMAN'S SHOW BBC1 2016 - 2017 PSYCHOBITCHES (SERIES 1 & 2) Tiger Aspect/Sky Arts Director/Co-writer 2012 - 2015 Nominated for two British Comedy Awards 2013; Winner of the Rose d'Or for Best TV Comedy THE ARMSTRONG & MILLER Hat Trick / BBC1 Series 1, 2 & 3 SHOW Script Editor/ Writer 2007 - 2010 BAFTA Award Best Comedy 2010 BILLY GOAT Hat Trick / BBC 1 x 60' 2008 Northern Ireland /BBC1 FUNLAND BBC2 Co-creator, co-writer and Associate 2006 -

RTS TV Jobs Guide 2018

TV JOBS GUIDE HOWHOW TOTO TELETELE VVGETGET INTO INTO II SS II ON ON HOW TO SURVIVE AS A FREELANCER LOUIS THEROUX’S INTERVIEW TIPS WRITE THE NEXT LINE OF DUTY HOW TO GET THE PERFECT SHOT 5 Smart moves 6 A running start A foot in the door is the It’s the ultimate entry- first step, says Holly Close. level job and a hard Now you need to graft, but it can open keep it up all kinds of futures there 8 Cast your net wide Without you, the show would have no exclusives, no guests and no archive footage 12 Headline snapper Covering the news is all about hitting deadlines in the Story first face of unforseen 10 events Good storytelling is central to editing – and editing is central to all TV shows 14 Hear this! It’s all about knowing what’s possible, says Strictly’s Tony Revell It’s all in the light 13 The pros shed light on shooting Centre of big-budget 16 attention dramas Keep it raw, rather than falsely polished – you can be yourself and still stand out, says Chris Stark 2 20 Write now Line of Duty creator Jed Mercurio Making headlines took time out of filming 18 series 5 to share his advice for writers Follow your curiosity, says who want to see their work on screen Louis Theroux – but don’t forget your audience 22 Freelance survival guide Job hunting How to make a success 24 What employers of self-employment – are looking for in and who to turn to for your CV, letter advice and support and interview 26 Get in training 28 Love TV? So do we Find out about a wide variety The RTS is committed to of training schemes from helping young people make broadcasters, producers and their way in television professional organisations Television is not an industry for the faint hearted, but the results can be hugely rewarding. -

Script Development As a ‘Wicked Problem’

CRAIG BATTY RMIT University RADHA O’MEARA University of Melbourne STAYCI TAYLOR RMIT University HESTER JOYCE La Trobe University PHILIPPA BURNE University of Melbourne NOEL MALONEY La Trobe University MARK POOLE RMIT University MARILYN TOFLER Swinburne University of Technology Script Development as a ‘Wicked Problem’ Abstract Both a process and a set of products, influenced by policy as well as people, and incorporating objective agendas at the same time as subjective experiences, script development is a core practice within the screen industry – yet one that is hard to pin down and, to some extent, define. From an academic research perspective, we might say that script development is a ‘wicked problem’ precisely because of these complex and often contradictory aspects. Following on from a recent Journal of Screenwriting special issue on script development (2017, vol. 8.3), and in particular an article therein dedicated to reviewing the literature and ‘defining the field’ (Batty et al 2017), an expanded team of researchers follow up on those ideas and insights. In this article, then, we attempt to theorise script development as a ‘wicked problem’ that spans a range of themes and disciplines. As a ‘wicked’ team of authors, our expertise encompasses screenwriting theory, screenwriting practice, film and television studies, cultural policy, ethnography, gender studies and comedy. By drawing on these critical 1 domains and creative practices, we present a series of interconnected themes that we hope not only suggests the potential for script development as a rich and exciting scholarly pursuit, but that also inspires and encourages other researchers to join forces in an attempt to solve the script development ‘puzzle’. -

Commissioning Process for Scriptwriting Commissioning Editor

The commissioning process for scriptwriting Commissioning Editor ! " The main role of the commissioning editor is to select programme ideas that they think are good enough to be aired. They will look through all of the submitted scripts before choosing the ones that they will think will work the best. Once they have chosen the best ideas they will give the production company a budget. ! " The commissioning editors work closely with the script writers. Each commissioning editor has an area that they specialise in e.g. drama, comedy… ! " They follow the production from when they give the production company the money all the way through until it is completed and released. Producer ! " The role of a producer is to deal with all areas of the production that the director does not deal with. These things include legal issues, cast and crew, budget and the marketing of a product. They work closely with the directors and other crew on set. The producer has control over who the director is and who is cast to play the characters. ! " Producers are responsible for making sure that the production stays within the allocated budget. ! " The producer is responsible for organizing everything. They organize props, costumes, actors and make sure facts are correct. Director ! " The director takes the pitched idea and turns it into the final product that the audience will see. ! " The director is responsible for all parts of the shoot. They have to supervise the placement of cameras, lighting equipment, microphones and props etc. ! " The director has complete control on what is happening on set. -

Gender Inequality and Screenwriters

GENDER INEQUALITY AND SCREENWRITERS A study of the impact of gender on equality of opportunity for screenwriters and key creatives in the UK film and television industries Authored By Alexis Kreager with Stephen Follows Introduction Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Foreword ............................................................................................................................................. 4 About the Commissioners ................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 6 Part One – Film ..................................................................................................................................... 20 1.1 Top-Level Stats ............................................................................................................................ 20 1.1a The Gender of UK Film Writers ............................................................................................. 20 1.1b Representation over Time .................................................................................................... 22 1.2 The Film Industry ........................................................................................................................ 24 1.2a -

Preserving Intellectual Freedom : Fighting Censorship in Our Schools / Edited by Jean F

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 374 463 CS 214 545 AUTHOR Brown, Jean E., Ed. TITLE Preserving Intellectual Freedom: Fighting Censorship in Our Schools. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-3671-0 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 261p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 36710-0015: $14.95 members, $19.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Freedom; * Censorship; Elementary Secondary Education; *English Curriculum; Intellectual Freedom; Language Arts; Moral Issues; Public Schools; *Student Rights; Teacher Response; Teaching Conditions IDENTIFIERS Controversial Materials; *Educational Issues; *Pressure Groups; Right to Education ABSTRACT Arguing that censorship is not simply an attempt to control what is taught in the schools but also an infringement on the legal learning rights of students, this collection of essays offers insights into how censorship can come about, its impacts and repercussions, and the ways it might be fought. The collection stresses action rather than reaction in guarding the preservation not just of the right to teach, but also. of the right to learn. After an introduction by the editor, the essays ar, as follows:(1) "In Defense of the Aesthetic: Technical Rationality and Cultural Censorship" (Philip M. Anderson);(2) "Policing Thought and Speech: What Happens to Intellectual Freedom?" (Jean E. Brown);(3) "Academic Freedom: Student Rights and Faculty Responsibilities" (David Moshman); (4) "Self-Censorship and the Elementary School Teacher" (Kathie Krieger Cerra);(5) "Literature, Intellectual Freedom, and the Ecology of the Imagination" (Hugh Agee);(6) "The Censorship of Young Adult Literature" (Margaret T. -

Bafta Rocliffe New Writing Showcase Ð Tv Drama 2019

A huge thank you to our script selection BAFTA Rocliffe patrons include: panellists and judges. They included: Christine Langan, Julian Fellowes, John Madden, Mike Newell, Richard Eyre, BAFTA ROCLIFFE David Parfitt, Peter Kosminsky, David Yates, TV Drama Jury Finola Dwyer, Michael Kuhn, Duncan NEW WRITING SHOWCASE Ð Kenworthy, Rebecca OÕBrien, Sue Perkins, POLLY HILL (Chair) Head of Drama, ITV John Bishop, Greg Brenmer, Olivia Hetreed, KATE ADORI Drama Development Executive, Channel 4 Television Andy Patterson and Andy Harries. TV DRAMA 2019 LUKE ALKIN Executive Producer, Drama, Big Talk Productions THURSDAY 28 NOVEMBER 2019 // ST JAMES'S PICCADILLY, 197 PICCADILLY, LONDON W1J 9LN CHLOE BEESON Development Assistant, Drama Republic Rocliffe Producers DANNY BROCKLEHURST Writer/Producer (Brassic, Shameless) VICTORIA FERGUSON [email protected] TARA FITZGERALD Actor (Game of Thrones) FARAH ABUSHWESHA BEN IRVING Drama Commissioning Editor, BBC [email protected] SARAH PHELPS is a screenwriter, FARAH ABUSHWESHA is a YVONNE ISIMEME IBAZEBO Producer (Top Boy, National Treasure) BAFTA Producer radio writer, playwright and BAFTA and European Film LOLA OLIYIDE Script Executive JULIA CARRUTHERS television producer. Early in her Academy nominated producer [email protected] ANNA PRICE Development Executive, The Forge career she began writing for the and Amazon best-selling author. SOPHIA RASHID Freelance Script Executive and Development Producer Directors popular soap EastEnders and has Her work includes The Singapore CAT RENTON Script Editor, Two Brothers -

Opening and Closing Credits

Opening and closing credits Opening credits: This section provides information on what categories may be used in Opening Credits. Note that opening credits may not credit the commissioning channel (e.g. "BBC ONE presents...") Programme-makers may choose from the following list of credits only. Note: Words in round brackets are optional; words in square brackets and sub-headings should not appear on screen. Opening Credits Credits that can be used Title [programme title] [and selection from the following, where appropriate] Performers (Cast) [main characters only] Starring [main characters only] Commentary by / Commentator Introduced by Presented by / Presenter Narrated by / Narrator Writers, creators, formats etc. Adapted by Based on an original idea by Based on the book by By Devised by / Deviser Dramatised by Format devised by From an idea by Screenplay by Series created by / Series creator Series devised by / Series deviser Written by / Writer Production / Editorial Producer / Produced by Director / Directed by [Only credits for performers may appear also in closing credits] Closing credits This section provides information on what categories may be used in Closing Credits. Programme-makers may choose from the following list of credits only. Note: Words in round brackets are optional; words in square brackets and sub-headings should not appear on screen. Reviewed February 2015 Performers (Cast) Cast/ Performers (in order of appearance) Commentary by / Commentator Guest(s) / Panellist(s) / Participant(s) Introduced by Presented by / -

1 Roles Will Normally Be Treated As

1 Roles will normally be treated as self-employed provided specific criteria from either column A or B, or both are met. (formerly Appendix 1). Column A - Criteria Column B - * Refer to the Production role What they do criteria in ESM 4115. DIRECTOR OF Has control over execution * Director of Photography Designs lighting and photography. PHOTOGRAPHY of tasks and conducts Responsible for the overall look of the preparatory work away from production. Decides on cameras and engager's premises. For lighting and other technical equipment further details see to be used. Is often autonomous in ESM0520, ESM0522 and decision making in relation to look, feel ESM0542 and technical equipment and advises the director. Responsible to the Director. AERIAL/UNDERWATER Has control over execution * Aerial/Underwater Specialises in Arial or Underwater DIRECTOR of tasks and conducts Director sequences. Designs lighting and preparatory work away from photography. Responsible for the engager's premises. For overall look of the production. Decides further details see on cameras and lighting and other ESM0520, ESM0522 and technical equipment to be used. Is ESM0542 often autonomous in decision making in relation to look, feel and technical equipment and advises the director. CAMERA OPERATOR Where the contract requires * Camera Supervisor Studio or Outdoor broadcasting (OB) the provision of substantial based, senior camera person. equipment to provide the Responsible for the look of the service without increased production and management of camera fee or other payment. For team. OFFICIAL 2 further details see ESM0540 Camera Operator Provides and operates camera and ESM0542 equipment, may work to a Director of Photography or camera supervisor. -

Following Hampton University's Censorship and Seizure of Its School

INSIDE:INSIDE: BrothersBrothers inin ChargeCharge inin Jackson,Jackson, MississippiMississippi || NABJ’sNABJ’s 15th15th PresidentPresident AimsAims HighHigh NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BLACK JOURNALISTS • WINTER 2004 NNABJAJOURNALBJ Staff of the Hampton Script The Silent Treatment Following Hampton University’s censorship and seizure of its school paper, NABJ examines HBCUs, student rights and the mis-education of black college journalists Nonprofit Org. U.S. Postage Paid Permit No. 161 Harrisonburg, VA NABJ members from around the nation form the association’s first gospel choir and sing praise at the Gospel Brunch in Dallas. PAGE 40 PHOTOGRAPH BY JO-ANN PIRSON SPECIAL REPORT FROM THE TOP ALSO INSIDE HBCU Mis-education? Black and in Charge Message from the Paper seizure at Hampton Executive editor Ronnie Executive Director University poses questions Agnew and managing editor PAGE 7 about what journalism Don Hudson are leading the Student’s Corner students are learning. way at The Clarion-Ledger in PAGE 34 PAGE 20 Jackson, Miss. PAGE 14 Associate’s Corner THE NABJ INTERVIEW PAGE 35 Q&A with NABJ’s CHAPTER SPOTLIGHT Talkin’ Tech 15th President Making Moves in S.D. PAGE 37 The San Diego Association of Herbert Lowe shares his Message from the vision for the association for Black Journalists makes its mark in the community. UNITY President the 2003-2005 term. PAGE 46 PAGE 33 PAGE 10 The NABJ Journal (USPS number pending) is published four times a year by the National Association of Black Journalists—the largest organization of journalists of color in the world. To discuss news items, photos and letters, call (301) 445-7100, ext.