The Total Filmmaker: Thinking of Screenwriting, Directing and Editing As One Role

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9780367508234 Text.Pdf

Development of the Global Film Industry The global film industry has witnessed significant transformations in the past few years. Regions outside the USA have begun to prosper while non-traditional produc- tion companies such as Netflix have assumed a larger market share and online movies adapted from literature have continued to gain in popularity. How have these trends shaped the global film industry? This book answers this question by analyzing an increasingly globalized business through a global lens. Development of the Global Film Industry examines the recent history and current state of the business in all parts of the world. While many existing studies focus on the internal workings of the industry, such as production, distribution and screening, this study takes a “big picture” view, encompassing the transnational integration of the cultural and entertainment industry as a whole, and pays more attention to the coordinated develop- ment of the film industry in the light of influence from literature, television, animation, games and other sectors. This volume is a critical reference for students, scholars and the public to help them understand the major trends facing the global film industry in today’s world. Qiao Li is Associate Professor at Taylor’s University, Selangor, Malaysia, and Visiting Professor at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon- Sorbonne. He has a PhD in Film Studies from the University of Gloucestershire, UK, with expertise in Chinese- language cinema. He is a PhD supervisor, a film festival jury member, and an enthusiast of digital filmmaking with award- winning short films. He is the editor ofMigration and Memory: Arts and Cinemas of the Chinese Diaspora (Maison des Sciences et de l’Homme du Pacifique, 2019). -

A Producer's Handbook

DEVELOPMENT AND OTHER CHALLENGES A PRODUCER’S HANDBOOK by Kathy Avrich-Johnson Edited by Daphne Park Rehdner Summer 2002 Introduction and Disclaimer This handbook addresses business issues and considerations related to certain aspects of the production process, namely development and the acquisition of rights, producer relationships and low budget production. There is no neat title that encompasses these topics but what ties them together is that they are all areas that present particular challenges to emerging producers. In the course of researching this book, the issues that came up repeatedly are those that arise at the earlier stages of the production process or at the earlier stages of the producer’s career. If not properly addressed these will be certain to bite you in the end. There is more discussion of various considerations than in Canadian Production Finance: A Producer’s Handbook due to the nature of the topics. I have sought not to replicate any of the material covered in that book. What I have sought to provide is practical guidance through some tricky territory. There are often as many different agreements and approaches to many of the topics discussed as there are producers and no two productions are the same. The content of this handbook is designed for informational purposes only. It is by no means a comprehensive statement of available options, information, resources or alternatives related to Canadian development and production. The content does not purport to provide legal or accounting advice and must not be construed as doing so. The information contained in this handbook is not intended to substitute for informed, specific professional advice. -

The Rise of Controversial Content in Film

The Climb of Controversial Film Content by Ashley Haygood Submitted to the Department of Communication Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Communication at Liberty University May 2007 Film Content ii Abstract This study looks at the change in controversial content in films during the 20th century. Original films made prior to 1968 and their remakes produced after were compared in the content areas of profanity, nudity, sexual content, alcohol and drug use, and violence. The advent of television, post-war effects and a proposed “Hollywood elite” are discussed as possible causes for the increase in controversial content. Commentary from industry professionals on the change in content is presented, along with an overview of American culture and the history of the film industry. Key words: film content, controversial content, film history, Hollywood, film industry, film remakes i. Film Content iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family for their unwavering support during the last three years. Without their help and encouragement, I would not have made it through this program. I would also like to thank the professors of the Communications Department from whom I have learned skills and information that I will take with me into a life-long career in communications. Lastly, I would like to thank my wonderful Thesis committee, especially Dr. Kelly who has shown me great patience during this process. I have only grown as a scholar from this experience. ii. Film Content iv Table of Contents ii. Abstract iii. Acknowledgements I. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………1 II. Review of the Literature……………………………………………………….8 a. -

FILM-1020: Story: Pre-Production Methods and the Art of Story in Motion Media 1

FILM-1020: Story: Pre-production Methods and the Art of Story in Motion Media 1 FILM-1020: STORY: PRE-PRODUCTION METHODS AND THE ART OF STORY IN MOTION MEDIA Cuyahoga Community College Viewing: FILM-1020 : Story: Pre-production Methods and the Art of Story in Motion Media Board of Trustees: 2018-05-24 Academic Term: Fall 2021 Subject Code FILM - Film and Media Arts Course Number: 1020 Title: Story: Pre-production Methods and the Art of Story in Motion Media Catalog Description: Study dramatic theory while writing an original script. Explore cultural uses of storytelling. Take real-life scenarios and respond to them with arguments constructed by the traditional elements of drama. Learn to write outlines, log lines, treatments, and character descriptions. Discuss facets of pre-production. Introduction to organizational tools and techniques used in film industry to prepare a script for production. Credit Hour(s): 3 Lecture Hour(s): 2 Lab Hour(s): 3 Requisites Prerequisite and Corequisite ENG-0995 Applied College Literacies, or appropriate score on English Placement Test; or departmental approval. Note: ENG-0990 Language Fundamentals II taken prior to Fall 2021 will also meet prerequisite requirements. Outcomes Course Outcome(s): Apply knowledge of story structure to a written treatment for a motion media production. Objective(s): 1. Identify the theme and dramatic or persuasive intent of the story. 2. Apply the art of storytelling to achieve a communications need (motivate and persuade) by creating a script for a short commercial or public service announcement (PSA). 3. Define the phases of a production from initial concept, treatment, pre-production, production, post-production and distribution. -

Project Information Form

PROJECT INFORMATION FORM - THEATRICAL This Project Information Form (PIF) should be filled out by an existing Directors Guild of America signatory company for each new theatrical film, low budget film or documentary film project or by a company requesting DGA signatory status. Please note that more detailed information may be required pending review by the Guild. Submission of this form does not constitute signatory acceptance. Please print clearly: Signatory Company: _________________________________________________________________________________________ Company Contact: ____________________________________________ Phone : _________________ E-Mail: _________________ Project Title: _______________________________________________________________________________________________ Copyright Holder: _______________________________________ Contact: ________________________ Phone: _______________ Screenwriter/s :_______________________________________________________________________________________________ Type: Feature Freelance Short Documentary Other:______________________ Low Budget Agreement : Yes No Budget: (U.S. ) $ ________________________________ Produced on : Film Digital Other (specify):__________________ Length (in minutes) : _______ Location/s: ________________________________________________________________________ Start Dates: Pre-Production:________________ Principal Photography :____________________ Wrap: _________________ EMPLOYEE INFORMATION (Name all, print clearly) : Print Full Name: Position: ‘ Director ‘ UPM ‘ -

7 1Stephen A

SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Bachelor of Fine Arts in Film Production New York University 1985 Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture & Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 1990 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1990 All Rights Reserved I Signature of Author Media Arts & Sciences Section Certified by '4 A Professor Glorianna Davenport Assistant Professor of Media Technology, MIT Media Laboratory Thesis Supervisor Accepted by I~ I ~ - -- 7 1Stephen A. Benton Chairperso,'h t fCommittee on Graduate Students OCT 0 4 1990 LIBRARIES iznteh Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLibraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Best copy available. SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture and Planning on August 10, 1990 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science ABSTRACT Film Production has always been a complex and costly endeavour. Since the early days of cinema, methodologies for planning and tracking production information have been constantly evolving, yet no single system exists that integrates the many forms of production data. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

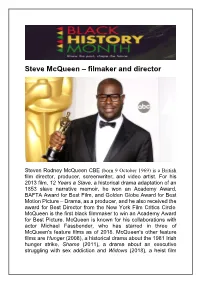

Steve Mcqueen – Filmaker and Director

Steve McQueen – filmaker and director Steven Rodney McQueen CBE (born 9 October 1969) is a British film director, producer, screenwriter, and video artist. For his 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, a historical drama adaptation of an 1853 slave narrative memoir, he won an Academy Award, BAFTA Award for Best Film, and Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, as a producer, and he also received the award for Best Director from the New York Film Critics Circle. McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. McQueen is known for his collaborations with actor Michael Fassbender, who has starred in three of McQueen's feature films as of 2018. McQueen's other feature films are Hunger (2008), a historical drama about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, Shame (2011), a drama about an executive struggling with sex addiction and Widows (2018), a heist film about a group of women who vow to finish the job when their husbands die attempting to do so. McQueen was born in London and is of Grenadianand Trinidadian descent. He grew up in Hanwell, West London and went to Drayton Manor High School. In a 2014 interview, McQueen stated that he had a very bad experience in school, where he had been placed into a class for students believed best suited "for manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." Later, the new head of the school would admit that there had been "institutional" racism at the time. McQueen added that he was dyslexic and had to wear an eyepatch due to a lazy eye, and reflected this may be why he was "put to one side very quickly". -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and Its American Legacy

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 3 (2010) 109–120 The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and its American legacy Jacqui Miller Liverpool Hope University (United Kingdom) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The French New Wave was an essentially pan-continental cinema. It was influenced both by American gangster films and French noirs, and in turn was one of the principal influences on the New Hollywood, or Hollywood renaissance, the uniquely creative period of American filmmaking running approximately from 1967–1980. This article will examine this cultural exchange and enduring cinematic legacy taking as its central intertext Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967). Some consideration will be made of its precursors such as This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942) and Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959) but the main emphasis will be the references made to Le Samourai throughout the New Hollywood in films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971), The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) and American Gigolo (Paul Schrader, 1980). The article will suggest that these films should not be analyzed as isolated texts but rather as composite elements within a super-text and that cross-referential study reveals the incremental layers of resonance each film’s reciprocity brings. This thesis will be explored through recurring themes such as surveillance and alienation expressed in parallel scenes, for example the subway chases in Le Samourai and The French Connection, and the protagonist’s apartment in Le Samourai, The Conversation and American Gigolo. A recent review of a Michael Moorcock novel described his work as “so rich, each work he produces forms part of a complex echo chamber, singing beautifully into both the past and future of his own mythologies” (Warner 2009). -

Summer 2019 Vol.21, No.3 Screenwriter Film | Television | Radio | Digital Media

CANADIAN CANADA $7 SUMMER 2019 VOL.21, NO.3 SCREENWRITER FILM | TELEVISION | RADIO | DIGITAL MEDIA A Rock Star in the Writers’ Room: Bringing Jann Arden to the small screen Crafting Canadian Horror Stories — and why we’re so good at it Celebrating the 23rd annual WGC Screenwriting Awards Emily Andras How she turned PM40011669 Wynonna Earp into a fan phenomenon Congratulations to Emily Andras of SPACE’s Wynonna Earp, Sarah Dodd of CTV’s Cardinal, and all of the other 2019 WGC Screenwriting Award winners. Proud to support Canada’s creative community. CANADIAN SCREENWRITER The journal of the Writers Guild of Canada Vol. 21 No. 3 Summer 2019 ISSN 1481-6253 Publication Mail Agreement Number 400-11669 Publisher Maureen Parker Editor Tom Villemaire [email protected] Contents Director of Communications Lana Castleman Cover Editorial Advisory Board There’s #NoChill When it Comes Michael Amo to Emily Andras’s Wynonna Earp 6 Michael MacLennan How 2019’s WGC Showrunner Award winner Emily Susin Nielsen Andras and her room built a fan and social media Simon Racioppa phenomenon — and why they’re itching to get back in Rachel Langer the saddle for Wynonna’s fourth season. President Dennis Heaton (Pacific) By Li Robbins Councillors Michael Amo (Atlantic) Features Mark Ellis (Central) What Would Jann Do? 12 Marsha Greene (Central) That’s exactly the question co-creators Leah Gauthier Alex Levine (Central) and Jennica Harper asked when it came time to craft a Anne-Marie Perrotta (Quebec) heightened (and hilarious) fictional version of Canadian Andrew Wreggitt (Western) icon Jann Arden’s life for the small screen. -

Lonesome (1928)

Lonesome (1928) By Raquel Stecher they’re really neighbors. The audience “In the whirlpool of modern life -- The suspends their disbelief for the joyous most difficult thing is to live alone.” reunion of the two lovebirds who will never be lonesome again. For the film industry, 1928 was a turbulent year. A major transition was If it wasn’t for the insistence of Fejos, occurring; one that would forever alter Lonesome might never have been how movies were made. Just one year made. Much like the industry itself, prior, The Jazz Singer (1927), a part- Fejos was in a state of transition. Born talkie, a silent film with a few talking and raised in Hungary, he studied sequences added in, would make a medicine, became a medical orderly splash in Hollywood. Audiences flocked during WWI and then switched careers to the theatres and the once reluctant and worked on films in his native studio heads realized that the transition country. He moved to New York City in to sound was inevitable. Filmmakers the 1920s but struggled to make ends scrambled to learn the new technology meet. He then moved to Hollywood and develop movies to go with it. In determined to make his first feature film. 1929 all-talking films became the With some hard work, ingenuity and standard and once the industry was well some help, he produced The Last into the 1930s silent filmmaking was Moment (1927). The film was officially a thing of the past. The time successful and Universal Pictures came between 1927 and 1929 was pivotal and calling.