Spatial Effects of Artificial Feeders on Hummingbird Abundance, Floral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Downloaded from Birdtree.Org [48] to Take Into Account Phylogenetic Uncertainty in the Comparative Analyses [67]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/downloaded-from-birdtree-org-48-to-take-into-account-phylogenetic-uncertainty-in-the-comparative-analyses-67-245125.webp)

Downloaded from Birdtree.Org [48] to Take Into Account Phylogenetic Uncertainty in the Comparative Analyses [67]

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/586362; this version posted November 19, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Distribution of iridescent colours in Open Peer-Review hummingbird communities results Open Data from the interplay between Open Code selection for camouflage and communication Cite as: preprint Posted: 15th November 2019 Hugo Gruson1, Marianne Elias2, Juan L. Parra3, Christine Recommender: Sébastien Lavergne Andraud4, Serge Berthier5, Claire Doutrelant1, & Doris Reviewers: Gomez1,5 XXX Correspondence: 1 [email protected] CEFE, Univ Montpellier, CNRS, Univ Paul Valéry Montpellier 3, EPHE, IRD, Montpellier, France 2 ISYEB, CNRS, MNHN, Sorbonne Université, EPHE, 45 rue Buffon CP50, Paris, France 3 Grupo de Ecología y Evolución de Vertrebados, Instituto de Biología, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia 4 CRC, MNHN, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, CNRS, Paris, France 5 INSP, Sorbonne Université, CNRS, Paris, France This article has been peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology 1 of 33 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/586362; this version posted November 19, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Identification errors between closely related, co-occurring, species may lead to misdirected social interactions such as costly interbreeding or misdirected aggression. This selects for divergence in traits involved in species identification among co-occurring species, resulting from character displacement. -

Brown2009chap67.Pdf

Swifts, treeswifts, and hummingbirds (Apodiformes) Joseph W. Browna,* and David P. Mindella,b Hirundinidae, Order Passeriformes), and between the aDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology & University nectivorous hummingbirds and sunbirds (Family Nec- of Michigan Museum of Zoology, 1109 Geddes Road, University tariniidae, Order Passeriformes), the monophyletic sta- b of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1079, USA; Current address: tus of Apodiformes has been well supported in all of the California Academy of Sciences, 55 Concourse Drive Golden Gate major avian classiA cations since before Fürbringer (3). Park, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA *To whom correspondence should be addressed (josephwb@ A comprehensive historical review of taxonomic treat- umich.edu) ments is available (4). Recent morphological (5, 6), genetic (4, 7–12), and combined (13, 14) studies have supported the apodiform clade. Although a classiA cation based on Abstract large DNA–DNA hybridization distances (4) promoted hummingbirds and swiJ s to the rank of closely related Swifts, treeswifts, and hummingbirds constitute the Order orders (“Trochiliformes” and “Apodiformes,” respect- Apodiformes (~451 species) in the avian Superorder ively), the proposed revision does not inP uence evolu- Neoaves. The monophyletic status of this traditional avian tionary interpretations. order has been unequivocally established from genetic, One of the most robustly supported novel A ndings morphological, and combined analyses. The apodiform in recent systematic ornithology is a close relation- timetree shows that living apodiforms originated in the late ship between the nocturnal owlet-nightjars (Family Cretaceous, ~72 million years ago (Ma) with the divergence Aegothelidae, Order Caprimulgiformes) and the trad- of hummingbird and swift lineages, followed much later by itional Apodiformes. -

Journal of Avian Biology JAV-00869 Wang, N

Journal of Avian Biology JAV-00869 Wang, N. and Kimball, R. T. 2016. Re-evaluating the distribution of cooperative breeding in birds: is it tightly linked with altriciality? – J. Avian Biol. doi: 10.1111/jav.00869 Supplementary material Appendix 1. Table A1. The characteristics of the 9993 species based on Jetz et al. (2012) Order Species Criteria1 Developmental K K+S K+S+I LB Mode ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter albogularis 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter badius 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter bicolor 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter brachyurus 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter brevipes 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter butleri 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter castanilius 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter chilensis 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter chionogaster 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter cirrocephalus 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter collaris 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter cooperii 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter erythrauchen 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter erythronemius 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter erythropus 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter fasciatus 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter francesiae 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter gentilis 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter griseiceps 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter gularis 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter gundlachi 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter haplochrous 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter henicogrammus 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter henstii 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter imitator 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES -

Eastern Venezuela

Rufous Crab Hawk (Eustace Barnes). EASTERN VENEZUELA 10 – 26 APRIL / 2 MAY 2016 LEADER: EUSTACE BARNES A spectacularly diverse biological haven; Venezuela is one of the most exciting destinations for birders although not one without its problems. Extending the tour to explore remote sites including the other-worldly summit of Mount Roraima makes for what is, the most adventurous and rewarding tour to this fascinating region. We had a record breaking tour with more of the endemics found than on any previous tour, finding 40 of the 42 possible Tepui endemics, while in the north-east we recorded all the endemics. This was helped in no small way by having such a committed group. We had difficulties in the Orinoco delta as we could not access the sites and, in the three years, since Birdquest was last in Venezuela the traditional rainforest sites have been destroyed making that element of the tour very difficult. This should make this document something of an interesting historical record. 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Eastern Venezuela. www.birdquest-tours.com Maguari Stork (left) and Orinocan Saltator (right) (Eustace Barnes(left) and Gary Matson(right)). Having arrived in Puerto Ordaz and enjoyed a restful night in a very plush hotel we were set to cross the Llanos de Monagas en route to Irapa on the Paria peninsula. We headed to the Rio Orinoco for our first stop just before the river. As we worked our way through the dusty scrub we quickly turned up a number of Orinocan Saltators which we watched awhile while taping in our first Yellow Orioles, Ochre-lored Flatbill, Tropical Gnatcatcher, Fuscous Flycatcher and numerous Bananaquits. -

Distribution of Iridescent Colours in Hummingbird Communities Results

Distribution of iridescent colours in hummingbird communities results from the interplay between selection for camouflage and communication Hugo Gruson, Marianne Elias, Juan Parra, Christine Andraud, Serge Berthier, Claire Doutrelant, Doris Gomez To cite this version: Hugo Gruson, Marianne Elias, Juan Parra, Christine Andraud, Serge Berthier, et al.. Distribution of iridescent colours in hummingbird communities results from the interplay between selection for camouflage and communication. 2020. hal-02372238v2 HAL Id: hal-02372238 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02372238v2 Preprint submitted on 3 Feb 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Distribution of iridescent colours in Open Peer-Review hummingbird communities results Open Data from the interplay between Open Code selection for camouflage and communication Cite as: Hugo G, Marianne E, Juan L. P, Christine A, Serge B, Claire D, and Doris G. Distribution of iridescent colours in hummingbird communities results from the interplay between Hugo Gruson1, Marianne Elias2, Juan L. Parra3, Christine selection for camouflage and communication. BioRxiv 586362, v5 4 5 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Andraud , Serge Berthier , Claire Doutrelant , & Doris Evolutionary Biology (2019). -

Breeds on Islands and Along Coasts of the Chukchi and Bering

FAMILY PTEROCLIDIDAE 217 Notes.--Also known as Common Puffin and, in Old World literature, as the Puffin. Fra- tercula arctica and F. corniculata constitutea superspecies(Mayr and Short 1970). Fratercula corniculata (Naumann). Horned Puffin. Mormon corniculata Naumann, 1821, Isis von Oken, col. 782. (Kamchatka.) Habitat.--Mostly pelagic;nests on rocky islandsin cliff crevicesand amongboulders, rarely in groundburrows. Distribution.--Breedson islandsand alongcoasts of the Chukchiand Bering seasfrom the DiomedeIslands and Cape Lisburnesouth to the AleutianIslands, and alongthe Pacific coast of western North America from the Alaska Peninsula and south-coastal Alaska south to British Columbia (QueenCharlotte Islands, and probablyelsewhere along the coast);and in Asia from northeasternSiberia (Kolyuchin Bay) southto the CommanderIslands, Kam- chatka,Sakhalin, and the northernKuril Islands.Nonbreeding birds occurin late springand summer south along the Pacific coast of North America to southernCalifornia, and north in Siberia to Wrangel and Herald islands. Winters from the Bering Sea and Aleutians south, at least casually,to the northwestern Hawaiian Islands (from Kure east to Laysan), and off North America (rarely) to southern California;and in Asia from northeasternSiberia southto Japan. Accidentalin Mackenzie (Basil Bay); a sight report for Baja California. Notes.--See comments under F. arctica. Fratercula cirrhata (Pallas). Tufted Puffin. Alca cirrhata Pallas, 1769, Spic. Zool. 1(5): 7, pl. i; pl. v, figs. 1-3. (in Mari inter Kamtschatcamet -

Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club

Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club Volume 139 No. 1 (Online) ISSN 2513-9894 (Online) March 2019 Club AnnouncementsAnnouncements 1 Bull.Bull. B.O.C.B.O.C. 20192019 139(1)139(1) Bulletin of the BRITISH ORNITHOLOGISTS’ CLUB Vol. 139 No. 1 Published 15 March 2019 CLUB ANNOUNCEMENTS The 992nd meeting of the Club was held on Monday 12 November 2018 in the upstairs room at the Barley Mow, 104 Horseferry Road, London SW1P 2EE. Twenty-fve people were present: Miss H. Baker, Mr P. J. Belman, Mr R. Bray, Mr S. Chapman, Ms J. Childers, Ms J. Day, Mr R. Dickey, Mr R. Gonzalez, Mr K. Heron, Ms J. Jones, Mr R. Langley, Dr C. F. Mann, Mr F. Martin, Mr D. J. Montier, Mr T. J. Pitman, Mr R. Price, Dr O. Prŷs-Jones, Dr R. Prŷs-Jones, Dr D. G. D. Russell, Mr P. Sandema, Mr S. A. H. Statham, Mr C. W. R. Storey (Chairman), Dr J. Tobias (Speaker), Mr J. Verhelst and Mr P. Wilkinson. Joe Tobias gave a talk entitled The shape of birds, and why it maters. Birds vary widely in size from the Bee Hummingbird Mellisuga helenae to Common Ostrich Struthio camelus, and come in a staggering range of shapes. Last century, the feld of eco-morphology began to shed light on the way birds are shaped by habitat preferences and foraging behaviour, but studies focused on relatively few species and left numerous gaps in understanding. Joe’s talk explored recent research based on detailed measurements of almost all of the world’s bird species, and described how this new infux of information has been combined with spatial, phylogenetic and ecological data to help answer some fundamental questions, such as how does bird diversity arise, and how can it best be conserved? REVIEWS McGhie, H. -

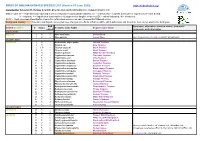

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus -

Avian Range Extensions from the Southern Headwaters of the Río Caroní, Gran Sabana, Bolívar, Venezuela

Cotinga31-090608:Cotinga 6/8/2009 2:38 PM Page 5 Cotinga 31 Avian range extensions from the southern headwaters of the río Caroní, Gran Sabana, Bolívar, Venezuela Anthony Crease Received 7 December 2005; final revision accepted 25 December 2008 first published online 4 March 2009 Cotinga 31 (2009): 5–19 Este artículo se refiere a mis observaciones de aves durante más de ocho años de residencia en la región de las cabeceras sureñas del río Caroní en la parte sur de la Gran Sabana, en el Estado Bolívar de Venezuela. Para 145 especies, presento nuevos registros que están significativamente distantes de los publicados o fuera de los rangos altitudinales establecidos para Venezuela al sur del Orinoco. La gran cantidad de observaciones ha sido resumida en una tabla para proveer información sobre la magnitud de las extensiones aparentes dentro de Venezuela, una indicación aproximada de la abundancia y distribución detallada dentro del área de estudio y sus diferentes tipos de hábitat. Se proveen descripciones más completas, incluyendo detalles de distribución en zonas circundantes, para algunas especies seleccionadas, para las cuales la distancia a los registros establecidos son mayores o donde existe evidencia respecto a movimientos estaciónales. Las especies tratadas incluyen Poecilotriccus fumifrons, conocida previamente en Venezuela de un solo espécimen colectado en el extremo sur del país en 1992. The Gran Sabana in south- east Venezuela, in itating the arrival of lowland savanna species from Bolívar state, comprises a remnant of a band of Roraima state in Brazil. elevated savannas that once separated the The study area (Fig. 1), a strip of land c.80 km Amazonian and Guianan lowlands. -

Building and Incubation at a Nest of Frilled Coquettes, Lophornis Magnifica (Trochilidae)

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 9: 77–80, 1998 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society BUILDING AND INCUBATION AT A NEST OF FRILLED COQUETTES, LOPHORNIS MAGNIFICA (TROCHILIDAE) Yoshika Oniki & Edwin O. Willis Departamento de Zoologia, UNESP, 13.506-900 Rio Claro, S.Paulo, Brazil. Key words: Frilled Coquette, incubation, Lophornis magnifica, nest-building. INTRODUCTION times/s. Teixeira et al. (1987) reported the weight of 2.2 g for two males. Oniki (1996) The Frilled Coquette (Lophornis magnifica, Tro- found an average value of 2.66 ± 0. 29 g (n = chilidae) is a small and sexually dimorphic 19) using Pesola scales. hummingbird, widely distributed in Brazil from Alagoas and Espírito Santo to Rio Grande do Sul and west through Goiás to STUDY AREA AND METHODS Mato Grosso (Meyer de Schauensee 1970, Teixeira et al. 1987). Schuchmann-Wegert & On 3 September 1994, Willis found a female Schuchmann (1986) summarize information building a cup nest 3 m up on a twig of a Jap- on the genus Lophornis including L. magnifica. anese plum (Eryobothrya japonica, Rosaceae) in Ruschi (1982) and Grantsau (1988) give illus- the orchard at the laboratory of the Biological trations and brief general information, includ- Reserve of Santa Lúcia (630 m elevation and ing nesting data, without specifying the 19°58’S, 40°32’W) on the Timbuí River just sources of their records or exact dates. Bur- below Santa Teresa, Espírito Santo, Brazil. meister (1856) reports that a small nest with Oniki and Willis observed nest building and little plant down was given to his son at Lagoa incubation over several days, to get direct Santa, Minas Gerais. -

Checklist of Species Within the CCBNEP Study Area: References, Habitats, Distribution, and Abundance

Current Status and Historical Trends of the Estuarine Living Resources within the Corpus Christi Bay National Estuary Program Study Area Volume 4 of 4 Checklist of Species Within the CCBNEP Study Area: References, Habitats, Distribution, and Abundance Corpus Christi Bay National Estuary Program CCBNEP-06D • January 1996 This project has been funded in part by the United States Environmental Protection Agency under assistance agreement #CE-9963-01-2 to the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission. The contents of this document do not necessarily represent the views of the United States Environmental Protection Agency or the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission, nor do the contents of this document necessarily constitute the views or policy of the Corpus Christi Bay National Estuary Program Management Conference or its members. The information presented is intended to provide background information, including the professional opinion of the authors, for the Management Conference deliberations while drafting official policy in the Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP). The mention of trade names or commercial products does not in any way constitute an endorsement or recommendation for use. Volume 4 Checklist of Species within Corpus Christi Bay National Estuary Program Study Area: References, Habitats, Distribution, and Abundance John W. Tunnell, Jr. and Sandra A. Alvarado, Editors Center for Coastal Studies Texas A&M University - Corpus Christi 6300 Ocean Dr. Corpus Christi, Texas 78412 Current Status and Historical Trends of Estuarine Living Resources of the Corpus Christi Bay National Estuary Program Study Area January 1996 Policy Committee Commissioner John Baker Ms. Jane Saginaw Policy Committee Chair Policy Committee Vice-Chair Texas Natural Resource Regional Administrator, EPA Region 6 Conservation Commission Mr. -

First Record of the Cf. Rufous-Crested Coquette, Lophornis Cf. Delattrei (Aves, Trochilidae), from Brazil

14 1 121 NOTES ON GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION Check List 14 (1): 121–124 https://doi.org/10.15560/14.1.121 First record of the cf. Rufous-crested Coquette, Lophornis cf. delattrei (Aves, Trochilidae), from Brazil Ricardo Antônio de Andrade Plácido,1 Leide Fernanda Almeida Fernandes,2 Roseanne de Fátima Ramos Almeida,3 Edson Guilherme4 1 Secretaria de Estado de Meio Ambiente do Acre, Departamento de Áreas Protegidas e Biodiversidade, Rua Marechal Deodoro, 572, 3o andar, Edifício Murard, Centro, Rio Branco, Acre, Brazil. CEP: 69900-330. 2 Condomínio Vivendas Bela Vista, casa F-19, Sobradinho, Distrito Federal, Brazil. CEP: 73105-909. 3 SQS 207, Bloco E, apartamento 205, Brasília, Distrito Federal, Brazil. CEP: 70253-050. 4 Universidade Federal do Acre, Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Natureza, Laboratório de Ornitologia. Campus Universitário, BR 364, km 04. Distrito industrial. Rio Branco, Acre, Brazil. CEP: 69.920-900. Corresponding author: Edson Guilherme, [email protected] Abstract The Rufous-crested Coquette, Lophornis delattrei (Lesson, 1839), and the Spangled Coquette, Lophornis stictolophus Salvin & Elliot, 1873, are 2 very similar species with a green back and orange forehead. On 9 August 2017, a hum- mingbird with an orange forehead was observed and photographed in the Serra do Divisor (Acre, Brazil). Analysis of the photographs revealed that the individual presented the diagnostic characteristics of a female of the Lophornis delattrei/stictolophus group. We assumed that the observed specimen represented Lophornis cf. delattrei, given the greater proximity of the geographic range of this species to the new locality. The presence of this Lophornis in Acre represents the occurrence of a new hummingbird taxon for Brazil.