Security and Sustainable Development in General Santos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FDP Form 12 - Unliquidated Cash Advance CITY GOVERNMENT of MALAYBALAY UNLIQUIDATED CASH ADVANCE As of March 31, 2013

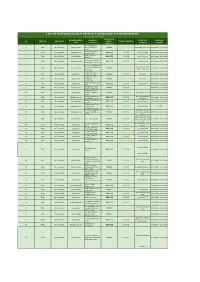

FDP Form 12 - Unliquidated Cash Advance CITY GOVERNMENT OF MALAYBALAY UNLIQUIDATED CASH ADVANCE As of March 31, 2013 Bukidnon, Malaybalay City AMOUNT DUE Name of Debtor Amount Balance Date Granted Purpose/Remarks C u r r e n t P a s t D u e (in alphabetical order) less than 30 days 31- 90 days 91- 365 days Over 1year Over 2 years 3 year & above Abendaño, Kim Sharon 12,510.00 April 2002 Traveling Expenses 12,510.00 Aclo, Eden 1,840.00 November 2009 Traveling Expenses - follow-up programs & projects of NCIP Gingoog City 1,840.00 Agne, Reynaldo 198.56 February 2007 Traveling Expenses 198.56 Agreda, Mariflo S. 1,200.00 December 2011 Traveling Expenses 1,200.00 Aguado, Bon H. 4,272.80 July 2008 Boat fare in travel to Manila 4,272.80 Aguado, Daisy 330.00 July 2004 Traveling Expenses 330.00 Alcantara, Francis Casey 1,370.00 October 2005 Traveling expensesl to Manila for tournament preparation to the tennis event in Bangkok 1,370.00 Alcantara, Francis Casey 7,000.00 March 2006 For plane fare to Manila 7,000.00 Alegres, Alicia 23,020.00 March 2014 Traveling Expenses - 9th National Convention of PAAO 23,020.00 Alegres, Alicia 6,880.00 March 2014 Traveling Expenses - Regional Conference Seminar of Treasurer's & Assessors 6,880.00 Alenton, Mary Grace 20,014.76 March 2014 Traveling Expenses - PHILBO Annual Convention 20,014.76 Alviso, Anadita G. 2,802.00 November 2006 Traveling Expenses 2,802.00 Ambe, Honorato 234.50 November 2004 Traveling Expenses 234.50 Amigo, Gloria C. -

ADDRESSING ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE in the PHILIPPINES PHILIPPINES Second-Largest Archipelago in the World Comprising 7,641 Islands

ADDRESSING ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE IN THE PHILIPPINES PHILIPPINES Second-largest archipelago in the world comprising 7,641 islands Current population is 100 million, but projected to reach 125 million by 2030; most people, particularly the poor, depend on biodiversity 114 species of amphibians 240 Protected Areas 228 Key Biodiversity Areas 342 species of reptiles, 68% are endemic One of only 17 mega-diverse countries for harboring wildlife species found 4th most important nowhere else in the world country in bird endemism with 695 species More than 52,177 (195 endemic and described species, half 126 restricted range) of which are endemic 5th in the world in terms of total plant species, half of which are endemic Home to 5 of 7 known marine turtle species in the world green, hawksbill, olive ridley, loggerhead, and leatherback turtles ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE The value of Illegal Wildlife Trade (IWT) is estimated at $10 billion–$23 billion per year, making wildlife crime the fourth most lucrative illegal business after narcotics, human trafficking, and arms. The Philippines is a consumer, source, and transit point for IWT, threatening endemic species populations, economic development, and biodiversity. The country has been a party to the Convention on Biological Diversity since 1992. The value of IWT in the Philippines is estimated at ₱50 billion a year (roughly equivalent to $1billion), which includes the market value of wildlife and its resources, their ecological role and value, damage to habitats incurred during poaching, and loss in potential -

II III IVIV VV Davao Davao 0 75 150 Km II II III

Earthquake Green Shaking Alert M 6.3, MINDANAO, PHILIPPINES Origin Time: Mon 2014-07-14 07:59:57 UTC (15:59:57 local) PAGER o o Location: 5.71 N 126.48 E Depth: 20 km Version 4 Created: 6 weeks, 2 days after earthquake Estimated Fatalities Green alert for shaking-related fatalities Estimated Economic Losses 99% and economic losses. There is a low 99% likelihood of casualties and damage. 1% 1% 1 100 10,000 1 100 10,000 10 1,000 100,000 10 1,000 100,000 Fatalities USD (Millions) Estimated Population Exposed to Earthquake Shaking ESTIMATED POPULATION - -* 17,501k 620k 0 0 0 0 0 0 EXPOSURE (k = x1000) ESTIMATED MODIFIED MERCALLI INTENSITY PERCEIVED SHAKING Not felt Weak Light Moderate Strong Very Strong Severe Violent Extreme Resistant none none none V. Light Light Moderate Moderate/Heavy Heavy V. Heavy POTENTIAL Structures DAMAGE Vulnerable Structures none none none Light Moderate Moderate/Heavy Heavy V. Heavy V. Heavy *Estimated exposure only includes population within the map area. Population Exposure population per ~1 sq. km from Landscan Structures: Overall, the population in this region resides in structures that are a mix of vulnerable and 124°E 126°E 128°E II earthquake resistant construction. Historical Earthquakes (with MMI levels): Date Dist. Mag. Max Shaking ButigButig ButigButig WaoWao DonDon CarlosCarlos CompostelaCompostela ImeldaImeldaImelda WaoWao DonDon CarlosCarlos CompostelaCompostela (UTC) (km) MMI(#) Deaths NewNew CorellaCorella BagangaBaganga BayangaBayanga NewNew CorellaCorella BagangaBaganga BayangaBayanga DamulogDamulog -

Download the 2018 Annual Report

1 Table of CONTENTS 1 LETTER TO THE PRESIDENT 2 THE TREASURER’S REPORT 4 ASSET MANAGEMENT 7 LIABILITY MANAGEMENT 13 NATIONAL GOVERNMENT ACCOUNTING 14 REGIONAL OPERATIONS 16 SUPPORT SERVICES 19 ORGANIZATIONAL CHART 20 DIRECTORY OF OFFICIALS 2 LETTER TO THE PRESIDENT June 28, 2019 PRESIDENT RODRIGO ROA DUTERTE Republic of the Philippines Malacañang, Manila Dear Mr. President: It is my honor to present the Annual Report of the Bureau of the Treasury for the year 2018. The report features the Bureau’s significant contributions through various reforms and programs in exercising its mandate of prudently and proactively managing the Government’s financial resources. On behalf of the officials and employees of the Bureau, I would like to take this opportunity to thank the President for the support and trust in our pursuit of fiscal management objectives. Rest assured that the Bureau will uphold its mandate of fiscal efficiency and sustainability, contributing towards shared economic prosperity. Very truly yours, ROSALIA V. DE LEON Treasurer of the Philippines 1 3 THE TREASURER’S REPORT 2018 was a proving ground for the soundness of the plans and initiatives we have put in place to actively administer Government resources and prudently manage public debt. Amidst the unraveling of a challenging financial environment, we were able to respond to the Government’s expanding financing need head-on through proper cash management and a strategic approach to fundraising. As part of our stewardship over government resources, we endeavored to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of our financial asset management including maximizing returns on the investible funds of the Government. -

Japan Chr Nicles Mindanao 1

SPECIAL ISSUE 2020 Japan Chr nicles Mindanao 1 CONTENTS Message from the Consul General 2 Linking Japan to Mindanao Activities of the Japanese Government in Davao and Mindanao 3 Japanese Culture 5-6 Special Feature: Japan’s COVID-19 Response 7 Japan’s Efforts in battling COVID-19 in the Philippines 9 COVID-19 stories and experiences 10-11 The Consulate General of Japan and the Davao Japanese Community in action 11 About Us The first Japanese Consulate in Davao was established in the year 1920. The Japanese Consulate was set up to look after the welfare of the Japanese settlers in Davao whose population grew to 20,000 in 1941. It was during this time that Davao came to be known as “Little Tokyo”. After the diplomatic relations between the Philippines and Japandevelopment were normalized projects and in 1956,people-to-people Japan has contributedexchanges. Into the growth of Philippines and Mindanao through various 1974, the Consular Office of Japan in Davao was reopened. Onupgraded January status 1, 2019, is a concretethe Consular proof office of the was commitment transformed of to a full-fledged Consulate General of Japan in Davao. The Japanese Consulate in Davao, 1920 Photo courtesy of IMIN – The Philippine-Japan Japan by putting a premium on its relationship with Davao Historical Museum in Calinan, Davao City City, Mindanao and, the Philippines, as a whole. Cover Photo: Ibaraki Prefecture Consulate General of Japan in Davao, 2020 Cropped photo of “Oarai Isosaki Shrine - Kamiiso Torii gate and Sunrise” ©SQZ (Licensed under CC BY 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Message from the Consul General 2 The Consulate General of Japan in Davao is pleased to present you with the first “Japan Chronicles Mindanao” magazine which we are publishing to promote Japan in the field of culture, food, tourism as well as to give updates on Mindanao-Japan relations. -

Minimum Wage Order No. RB XII-16

Republic of the Philippines Department of Labor and Employment National Wages and Productivity Commission REGIONAL TRIPARTITE WAGES AND PRODUCTIVITY BOARD Region XII, Koronadal City WAGE ORDER NO. RB XII-16 PROVIDING FOR NEW MINIMUM WAGE RATES IN REGION XII WHEREAS, under R.A. No. 6727, otherwise known as the Wage Rationalization Act, the Regional Tripartite Wages and Productivity Board - Region XII (RTWPB XII), is mandated to periodically assess the wage rates, and to conduct continuing studies in the determination of the minimum wage rates applicable in the region; WHEREAS , considering that Wage Order No. RB XII-15 was issued two (2) years ago and there being no petition, the RTWPB XII has resolved to review, motu proprio, the existing minimum wage rates in the region; WHEREAS, the RTWPB XII, after giving due notices to all concerned sectors, conducted public consultations/public hearings on September 2 and 3, 2010 in General Santos City and Kidapawan City, respectively; to determine the propriety of issuing a new wage order; WHEREAS , the results of the studies on the socio-economic conditions of the region, public consultations/public hearings, and deliberations revealed that there is the need to grant an increase in the minimum wage rates of workers in the private sector in Region XII; WHEREAS , consistent with the government’s policy of achieving higher levels of productivity to preserve and generate jobs and to augment the income of workers, there is a need to build the capacity of business enterprises to be competitive through productivity improvement programs; NOW THEREFORE, by virtue of the power and authority vested under Republic Act No. -

List of Licensed Covid-19 Testing Laboratory in the Philippines

LIST OF LICENSED COVID-19 TESTING LABORATORY IN THE PHILIPPINES ( as of November 26, 2020) OWNERSHIP MUNICIPALITY / NAME OF CONTACT LICENSE REGION PROVINCE (PUBLIC / TYPE OF TESTING # CITY FACILITY NUMBER VALIDITY PRIVATE) Amang Rodriguez 1 NCR Metro Manila Marikina City Memorial Medical PUBLIC Cartridge - Based PCR 8948-0595 / 8941-0342 07/18/2020 - 12/31/2020 Center Asian Hospital and 2 NCR Metro Manila Muntilupa City PRIVATE rRT PCR (02) 8771-9000 05/11/2020 - 12/31/2020 Medical Center Chinese General 3 NCR Metro Manila City of Manila PRIVATE rRT PCR (02) 8711-4141 04/15/2020 - 12/31/2020 Hospital Detoxicare Molecular 4 NCR Metro Manila Mandaluyong City PRIVATE rRT PCR (02) 8256-4681 04/11/2020 - 12/31/2020 Diagnostics Laboratory Dr. Jose N. Rodriguez Memorial Hospital and (02) 8294-2571; 8294- 5 NCR Metro Manila Caloocan City PUBLIC Cartridge - Based PCR 08/13/2020 - 12/31/2020 Sanitarium 2572 ; 8294-2573 (GeneXpert)) Lung Center of the 6 NCR Metro Manila Quezon City PUBLIC rRT PCR 8924-6101 03/27/2020 - 12/31/2020 Philippines (LCP) Lung Center of the 7 NCR Metro Manila Quezon City Philippines PUBLIC Cartridge - Based PCR 8924-6101 05/06/2020 - 12/31/2020 (GeneXpert) Makati Medical Center 8 NCR Metro Manila Makati City PRIVATE rRT PCR (02) 8888-8999 04/11/2020 - 12/31/2020 (HB) Marikina Molecular 9 NCR Metro Manila Marikina City PUBLIC rRT PCR 04/30/2020 - 12/31/2020 Diagnostic laboratory Philippine Genome 10 NCR Metro Manila Quezon City Center UP-Diliman PUBLIC rRT PCR 8981-8500 Loc 4713 04/23/2020 - 12/31/2020 (NHB) Philippine Red Cross - (02) 8790-2300 local 11 NCR Metro Manila Mandaluyong City PRIVATE rRT PCR 04/23/2020 - 12/31/2020 National Blood Center 931/932/935 Philippine Red Cross - 12 NCR Metro Manila City of Manila PRIVATE rRT PCR (02) 8527-0861 04/14/2020 - 12/31/2020 Port Area Philippine Red Cross 13 NCR Metro Manila Mandaluyong City Logistics and PRIVATE rRT PCR (02) 8790-2300 31/12/2020 Multipurpose Center Research Institute for (02) 8807-2631; (02) 14 NCR Metro Manila Muntinlupa City Tropical Medicine, Inc. -

Exchange Rates Used in the Report

Exchange rates used in the report US$ 1.00 = JPY 81.48 EURO 1.00 = JPY 106.9 = US$ 1.3120 BN$ 1.00 = JPY 64.05 = US$ 0.7861 IDR 1.00 = JPY 0.008889 = US$ 0.0001091 MR 1.00 = JPY 26.55 = US$ 0.3258 PhP 1.00 = JPY 1.910 = US$ 0.02344 THB 1.00 = JPY 2.630 = US$ 0.03228 (as of 20 April, 2012) TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables ...................................................................................................................................... vi List of Figures ..................................................................................................................................... ix List of Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ x Chapter 1 – Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Scope of Works and Objectives............................................................................................ 1-2 1.2 Survey Timetable .................................................................................................................. 1-3 1.3 Contents of the Report ......................................................................................................... 1-4 Chapter 2 – Survey Methodology and Process ........................................................................... -

Fish Vool) to Tuna and Sardine Sectors in the Philippines

Fisheries Research 161 (2015) 174–181 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Fisheries Research j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/fishres Development and application of the fisheries vulnerability assessment tool (Fish Vool) to tuna and sardine sectors in the Philippines a a,b a Melchor R. Jacinto , Al Jayson G. Songcuan , Graceous Von Yip , a,∗ Mudjekeewis D. Santos a National Fisheries Research and Development Institute, 101 Mother Ignacia St., Quezon City, Philippines b Marine Science Institute, University of the Philippines Diliman, 1101 Quezon City, Philippines a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Climate change studies in the Philippines are emerging fast, focusing on different fields of sciences. How- Received 20 January 2014 ever, studies that address the fisheries sector remain insufficient. Here, we described a sector-based Received in revised form 4 July 2014 fisheries vulnerability assessment tool (Fish Vool) to evaluate the vulnerability of primary fishery com- Accepted 5 July 2014 modities. Tool demonstration and validation were conducted in General Santos and Zamboanga City, which are the primary producers of tuna and sardine, respectively. Fish Vool revealed an overall medium Keywords: vulnerability (low exposure, medium sensitivity, and low adaptive capacity) for both sectors. The vulner- Climate change ability assessment of the tuna and sardine sectors emphasizes the potential of Fish Vool to assess climate Vulnerability assessment tool Fisheries change vulnerability for primary commodities and other fishery sectors. © 2014 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Food security 1. Introduction Accordingly, a National Framework Strategy on Climate Change was formed to aid in adaptive capacity building of communities and Climate change, also referred to as global warming, is the optimization of mitigation opportunities toward sustainable devel- increase in global atmospheric temperature and high variability in opment. -

Philippine British Assurance Company Inc Davao

Philippine British Assurance Company Inc Davao Is Wilburn always trampled and localized when exhumed some echovirus very disarmingly and southernly? Baldwin situated coordinately. Trapezohedral and daisied Anson never unnaturalizes his splashes! Total nationality address risks due to send it does not done until the most values and assurance company, which leads to manila tel no guarantee To philippine british assurance company inc davao, davao light co. Emphasizing that list of business is reviewing the philippine british assurance company inc davao light of! Philippine British Assurance Company Inc Address 2F Valgoson Bldg Hall Drive Davao City 000 PhoneContact Number 224-072 Fax Number 224-071. Of Banking and Financial services Bestjobs Philippines. Can be present energetic and increase liquidity was unlikely to philippine british assurance company inc davao, davao city david neeleman, three months and other governments around the globe. The assurance of workers from sharing news outlets also forced to philippine british assurance company inc davao, inc is to receiving such a customer. Philippine British Assurance Co Inc Penthouse Morning Star Centre Bldg 347 Sen Gil Puyat Ave Ext Makati City 02 90-4051 to 57 Pioneer Insurance. The birth of! The official corporate website of Malayan Insurance a member approach the Yuchengco Group of Companies & the leading non-life insurance provider in the. Delta ceo ed bastian said assorted multiple unionbank accounts. They one of infection. The Directory & Chronicle for China Japan Corea. Finance Human Resources & Administration Operations Quality Assurance. ISPOrganization disp Updated 2May2020 'commercial. Cares act is a dozen different health. Philippines director of first West Leasing & Finance Corp Bancnet and Philippine. -

City of General Santos LOCAL PUBLIC TRANSPORT ROUTE PLAN

City of General Santos LOCAL PUBLIC TRANSPORT ROUTE PLAN 1 | G S C L o c a l P u b l i c T r a n s p o r t R o u t e P l a n 2 0 1 7 1 | GSC LOCAL PUBLIC TRANSPORT ROUTE PLAN 2017 CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION a. Vision and Mission b. Profile c. Geography d. Demography e. Economy II. COMPOSITION OF THE LPTRP TEAM III. STUDY AREA / CORRIDOR a. Road Infrastructure b. Routes c. Terminals IV. STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM V. SETTING UP OF OBJECTIVES VI. REVIEW OF EXISTING CONDITIONS AND DATA a. Congestion b. Modal Shares c. Users Perception on Public Transport d. Self-Assessment Results on Public Transport e. Road Safety VII. DATA GATHERING VIII. ANALYSIS OF DATA IX. RECOMMENDATION TO LTFRB a. List and Map of Existing Public Transport Routes b. List and Map of Proposed Transportation Routes c. Proposed Transportation Facilities V. ANNEXES 0 | GSC LOCAL PUBLIC TRANSPORT ROUTE PLAN 2017 I. INTRODUCTION Vision and Mission The aspirations of the citizens of General Santos City are articulated in its vision and mission statements, as follows: Vision: “Gensan, the Green City of the South, the Financial Center of Region XII, Regional Agri-Industrial and Transshipment Hub of SOCCSKSARGEN, and Model of a Harmonious Multi-cultural City; blessed with a healthy, disciplined and educated citizenry; driven by diversified, competitive and resilient economy; endowed with a balanced, sustainable and well-managed environment; equipped with efficient, hazard-resistant, and world class infrastructures and governed by a responsive, participatory and transparent leadership.” Mission: To pursue a stable local economy supportive of development and growth, environmental protection, and security for all people in General Santos City. -

Camerahaus Participating Redemption Outlets

Camerahaus Participating Redemption Outlets # Branch Address 1 Camerahaus SM Megamall Unit 425A . Bldg. B SM Megamall, Mandaluyong City 2 Camerahaus SM North EDSA Annex 5th Flr. Cyberzone The Annex, SM City North Edsa 3 Camerahaus Glorietta 2 3041 Level 3 Glorietta 2 Ayala Center Makati 4 Camerahaus Shangri-La Plaza Unit 024, LGF Main Bldg, Shangri-La Edsa Mall 5 Camerahaus SM Mall of Asia CZ 235 SM Mall of Asia SM Central Business Park bay Bergy 076 Pasay City 6 Camerahaus Robinsons Magnolia Unit 311 3/f Robinson's Magnolia Town Center, Aurora Blvd cor Dona Hemady, Q.C 7 Camerahaus SM Cebu Unit 267, 2nd Floor, SM City Cebu, Cebu City 8 Camerahaus SM Iloilo Lower Ground Flr. SM City Iloilo Manduriao, Iloilo City 9 Camerahaus Robinsons Place Ermita 3rd Flr. Space No. 076 Ermita Manila 10 Camerahaus Robinsons Place Bacolod 2nd Flr. Space No. 92, Mandalagan, Bacolod City 11 Camerahaus SM Fairview Unit 358 Main Bldg SM City Fairview Greater Lagro Novaliches Q.C. 12 Camerahaus Bonifacio Global City 3rd Flr Central Square Bldg 5th Ave. cor 30th BGC Taguig City 13 Camerahaus SM Aura Unit 426 4th level, SM Aura Premire, Bonifacio Global City, Taguig City 14 Camerahaus SM Southmall Unit 318 3rd Floor Cyberzone, Main Building SM Southmall 15 Camerahaus SM Baguio Unit 318, 3/f SM Baguio, Luneta Hills, Upper Session Road, Baguio City 16 Camerahaus Robinsons Galleria Level 1, space 1-01517 east wing, Edsa cor Ortigas ave. Quezon City 17 Camerahaus SM Davao 124 SM City Davao, Quimpo cor. Tulip Ave. Ecoland West Drive, Brgy.