Tagum City: Development at the Crossroads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

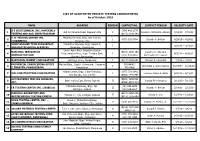

III III III III LIST of ACCREDITED PRIVATE TESTING LABORATORIES As of October 2019

LIST OF ACCREDITED PRIVATE TESTING LABORATORIES As of October 2019 NAME ADDRESS REGION CONTACT NO. CONTACT PERSON VALIDITY DATE A’S GEOTECHNICAL INC. MATERIALS (074) 442-2775 1 Old De Venecia Road, Dagupan City I Dioscoro Richard B. Alviedo 7/16/19 – 7/15/21 TESTING AND SOIL INVESTIGATION (0917) 1141-343 E. B. TESTING CENTER INC. McArthur Hi-way, Brgy. San Vicente, 2 I (075) 632-7364 Elnardo P. Bolivar 4/29/19 – 4/28/21 (URDANETA) Urdaneta City JORIZ GROUND TECH SUBSURFACE MacArthur Highway, Brgy. Surabnit, 3 I 3/20/18 – 3/19/20 AND GEOTECHNICAL SERVICES Binalonan, Pangasinan Lower Agno River Irrigation System NATIONAL IRRIGATION (0918) 8885-152 Ceferino C. Sta. Ana 4 Improvement Proj., Brgy. Tomana East, I 4/30/19 – 4/29/21 ADMINISTRATION (075) 633-3887 Rommeljon M. Leonen Rosales, Pangasinan 5 NORTHERN CEMENT CORPORATION Labayug, Sison, Pangasinan I (0917) 5764-091 Vincent F. Cabanilla 7/3/19 – 7/2/21 PROVINCIAL ENGINEERING OFFICE Malong Bldg., Capitol Compound, Lingayen, 542-6406 / 6 I Antonieta C. Delos Santos 11/23/17 – 11/22/19 (LINGAYEN, PANGASINAN) Pangasinan 542-6468 Valdez Center, Brgy. 1 San Francisco, (077) 781-2942 7 VVH CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION I Francisco Wayne B. Butay 6/20/19 – 6/19/21 San Nicolas, Ilocos Norte (0966) 544-8491 ACCURATEMIX TESTING SERVICES, (0906) 4859-531 8 Brgy. Muñoz East, Roxas, Isabela II Juanita Pine-Ordanez 3/11/19 – 3/10/21 INC. (0956) 4078-310 Maharlika Highway, Brgy. Ipil, (02) 633-6098 9 EB TESTING CENTER INC. (ISABELA) II Elnardo P. Bolivar 2/14/18 – 2/13/20 Echague, Isabela (02) 636-8827 MASUDA LABORATORY AND (0917) 8250-896 10 Marana 1st, City of Ilagan, Isabela II Randy S. -

Rapid Market Appraisal for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao Del Sur (Brackishwater Areas)

Rapid Market Appraisal for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) AMC MINI PROJECT: TEAM TILAPIA Acuna, Thaddeus R., UP Mindanao Almazan, Cynthia V., DOST-PCAARRD Castillo, Monica, DOST-PCAARRD Romo, Glory Dee A., UP Mindanao Rosetes, Mercy A., Foodlink Advocacy Co-operative (FAC) RMA for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) OBJECTIVE To conduct a market assessment of expanding areas for tilapia culture production in costal and brackishwater areas in the province of Davao del Sur. RMA for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) RESEARCH QUESTIONS 1. Does consumption level of Tilapia a key contributing factor for potential expansion of Tilapia production in Davao del Sur? 2. Is the market potential of competitiveness of Tilapia substantial enough to revitalize tilapia production in Davao del Sur? RMA for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) METHODOLOGY RAPID APPRAISAL APPROACH Secondary data Encoding Market Areas for gathering Constraints Intervention Primary data Market gathering Competitiveness * KIs Market * Market Mapping Opportunities * Market Visits A Step-by step approach of Rapid Market Appraisal (Adapted from the RMA proposal for underutilized fruits) RMA for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) INDUSTRY SITUATION ✓ Tilapia is a major aquaculture product in the Philippines that is considered important to the country’s food security and nutrition (Perez, 2017) ✓ Most -

FDP Form 12 - Unliquidated Cash Advance CITY GOVERNMENT of MALAYBALAY UNLIQUIDATED CASH ADVANCE As of March 31, 2013

FDP Form 12 - Unliquidated Cash Advance CITY GOVERNMENT OF MALAYBALAY UNLIQUIDATED CASH ADVANCE As of March 31, 2013 Bukidnon, Malaybalay City AMOUNT DUE Name of Debtor Amount Balance Date Granted Purpose/Remarks C u r r e n t P a s t D u e (in alphabetical order) less than 30 days 31- 90 days 91- 365 days Over 1year Over 2 years 3 year & above Abendaño, Kim Sharon 12,510.00 April 2002 Traveling Expenses 12,510.00 Aclo, Eden 1,840.00 November 2009 Traveling Expenses - follow-up programs & projects of NCIP Gingoog City 1,840.00 Agne, Reynaldo 198.56 February 2007 Traveling Expenses 198.56 Agreda, Mariflo S. 1,200.00 December 2011 Traveling Expenses 1,200.00 Aguado, Bon H. 4,272.80 July 2008 Boat fare in travel to Manila 4,272.80 Aguado, Daisy 330.00 July 2004 Traveling Expenses 330.00 Alcantara, Francis Casey 1,370.00 October 2005 Traveling expensesl to Manila for tournament preparation to the tennis event in Bangkok 1,370.00 Alcantara, Francis Casey 7,000.00 March 2006 For plane fare to Manila 7,000.00 Alegres, Alicia 23,020.00 March 2014 Traveling Expenses - 9th National Convention of PAAO 23,020.00 Alegres, Alicia 6,880.00 March 2014 Traveling Expenses - Regional Conference Seminar of Treasurer's & Assessors 6,880.00 Alenton, Mary Grace 20,014.76 March 2014 Traveling Expenses - PHILBO Annual Convention 20,014.76 Alviso, Anadita G. 2,802.00 November 2006 Traveling Expenses 2,802.00 Ambe, Honorato 234.50 November 2004 Traveling Expenses 234.50 Amigo, Gloria C. -

Volume Xxiii

ANTHROPOLOGICAL PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY VOLUME XXIII NEW YORK PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES 1925 Editor CLARK WISSLER FOREWORD Louis ROBERT SULLIVAN Since this volume is largely the work of the late Louis Robert Sulli- van, a biographical sketch of this able anthropologist, will seem a fitting foreword. Louis Robert Sullivan was born at Houlton, Maine, May 21, 1892. He was educated in the public schools of Houlton and was graduated from Bates College, Lewiston, Maine, in 1914. During the following academic year he taught in a high school and on November 24, 1915, he married Bessie Pearl Pathers of Lewiston, Maine. He entered Brown University as a graduate student and was assistant in zoology under Professor H. E. Walters, and in 1916 received the degree of master of arts. From Brown University Mr. Sullivan came to the American Mu- seum of Natural History, as assistant in physical anthropology, and during the first years of his connection with the Museum he laid the foundations for his future work in human biology, by training in general anatomy with Doctor William K. Gregory and Professor George S. Huntington and in general anthropology with Professor Franz Boas. From the very beginning, he showed an aptitude for research and he had not been long at the Museum ere he had published several important papers. These activities were interrupted by our entrance into the World War. Mr. Sullivan was appointed a First Lieutenant in the Section of Anthropology, Surgeon-General's Office in 1918, and while on duty at headquarters asisted in the compilation of the reports on Defects found in Drafted Men and Army Anthropology. -

ADDRESSING ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE in the PHILIPPINES PHILIPPINES Second-Largest Archipelago in the World Comprising 7,641 Islands

ADDRESSING ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE IN THE PHILIPPINES PHILIPPINES Second-largest archipelago in the world comprising 7,641 islands Current population is 100 million, but projected to reach 125 million by 2030; most people, particularly the poor, depend on biodiversity 114 species of amphibians 240 Protected Areas 228 Key Biodiversity Areas 342 species of reptiles, 68% are endemic One of only 17 mega-diverse countries for harboring wildlife species found 4th most important nowhere else in the world country in bird endemism with 695 species More than 52,177 (195 endemic and described species, half 126 restricted range) of which are endemic 5th in the world in terms of total plant species, half of which are endemic Home to 5 of 7 known marine turtle species in the world green, hawksbill, olive ridley, loggerhead, and leatherback turtles ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE The value of Illegal Wildlife Trade (IWT) is estimated at $10 billion–$23 billion per year, making wildlife crime the fourth most lucrative illegal business after narcotics, human trafficking, and arms. The Philippines is a consumer, source, and transit point for IWT, threatening endemic species populations, economic development, and biodiversity. The country has been a party to the Convention on Biological Diversity since 1992. The value of IWT in the Philippines is estimated at ₱50 billion a year (roughly equivalent to $1billion), which includes the market value of wildlife and its resources, their ecological role and value, damage to habitats incurred during poaching, and loss in potential -

II III IVIV VV Davao Davao 0 75 150 Km II II III

Earthquake Green Shaking Alert M 6.3, MINDANAO, PHILIPPINES Origin Time: Mon 2014-07-14 07:59:57 UTC (15:59:57 local) PAGER o o Location: 5.71 N 126.48 E Depth: 20 km Version 4 Created: 6 weeks, 2 days after earthquake Estimated Fatalities Green alert for shaking-related fatalities Estimated Economic Losses 99% and economic losses. There is a low 99% likelihood of casualties and damage. 1% 1% 1 100 10,000 1 100 10,000 10 1,000 100,000 10 1,000 100,000 Fatalities USD (Millions) Estimated Population Exposed to Earthquake Shaking ESTIMATED POPULATION - -* 17,501k 620k 0 0 0 0 0 0 EXPOSURE (k = x1000) ESTIMATED MODIFIED MERCALLI INTENSITY PERCEIVED SHAKING Not felt Weak Light Moderate Strong Very Strong Severe Violent Extreme Resistant none none none V. Light Light Moderate Moderate/Heavy Heavy V. Heavy POTENTIAL Structures DAMAGE Vulnerable Structures none none none Light Moderate Moderate/Heavy Heavy V. Heavy V. Heavy *Estimated exposure only includes population within the map area. Population Exposure population per ~1 sq. km from Landscan Structures: Overall, the population in this region resides in structures that are a mix of vulnerable and 124°E 126°E 128°E II earthquake resistant construction. Historical Earthquakes (with MMI levels): Date Dist. Mag. Max Shaking ButigButig ButigButig WaoWao DonDon CarlosCarlos CompostelaCompostela ImeldaImeldaImelda WaoWao DonDon CarlosCarlos CompostelaCompostela (UTC) (km) MMI(#) Deaths NewNew CorellaCorella BagangaBaganga BayangaBayanga NewNew CorellaCorella BagangaBaganga BayangaBayanga DamulogDamulog -

NDRRMC Update Sitrep No. 48 Flooding & Landslides 21Jan2011

FB FINELY (Half-submerged off Diapila Island, El Nido, Palawan - 18 January 2011) MV LUCKY V (Listed off the Coast of Aparri, Cagayan - 18 Jan) The Pineapple – a 38-footer Catamaran Sailboat twin hulled (white hull and white sails) departed Guam from Marianas Yatch Club 6 January 2011 which is expected to arrive Cebu City on 16 January 2011 but reported missing up to this time Another flooding and landslide incidents occurred on January 16 to 18, 2011 in same regions like Regions IV-B, V, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI and ARMM due to recurrence of heavy rains: Region IV-B Thirteen (13) barangays were affected by flooding in Narra, Aborllan, Roxas and Puerto Princesa City, Palawan Region V Landslide occurred in Brgy. Calaguimit, Oas, Albay on January 20, 2011 with 5 houses affected and no casualty reported as per report of Mayor Gregorio Ricarte Region VII Brgys Poblacion II and III, Carcar, Cebu were affected by flooding with 50 families affected and one (1) missing identified as Sherwin Tejada in Poblacion II. Ewon Hydro Dam in Brgy. Ewon and the Hanopol Hydro Dam in Brgy. Hanopol all in Sevilla, Bohol released water. Brgys Bugang and Cambangay, Brgys. Napo and Camba in Alicia and Brgys. Canawa and Cambani in Candijay were heavily flooded Region VIII Brgys. Camang, Pinut-an, Esperanza, Bila-tan, Looc and Kinachawa in San Ricardo, Southern Leyte were declared isolated on January 18, 2011 due to landslide. Said areas werer already passable since 19 January 2011 Region IX Brgys San Jose Guso and Tugbungan, Zamboanga City were affected by flood due to heavy rains on January 18, 2011 Region X One protection dike in Looc, Catarman. -

Pdf | 329.37 Kb

C. AFFECTED POPULATION (TAB C) A total of 173,617 families/830,117 persons were affected in 822 barangays in 103 municipalities in 15 provinces of Regions X, XI, CARAGA and ARMM Out of the total affected, 44,766 families / 206,888 persons were displaced and served inside 569 evacuation centers D. STATUS OF STRANDEES (as of 7:00 PM, 21 January 2014) ROLLING STRANDED PASSENGERS VESSELS MBCA’s CARGOES CGDCV CGS Cebu 6 5 CGDEV CGS Catabalogan 639 3 111 TOTAL 639 9 111 5 E. STATUS OF LIFELINES A total of 50 roads and 25 bridges are still not passable in Regions VIII, X, XI and CARAGA (TAB D) Mate, Bacolod Water System, Brgy. Purakan and Brgy. Bosque Linamon water pipes were damaged in Lanao del Norte The province of Dinagat Islands experienced total blackout on 17 January 2014 due to heavy rains and strong winds but resumed electricity earlier of 18 January 2014 F. STATUS OF MAJOR RIVERS AND DAMS Saug River, Asuncion, Davao del Norte – Overflowed Libuganon River, Kapalong, Davao del Norte – Overflowed Irrigation Dams in Aragon and Brgy Taytayan in Cateel, Davao Oriental were damaged due to flooding G. DAMAGED HOUSES (TAB E) The number of damages houses increased to 2,109 houses (831 totally/1,278 partially). H. COST OF DAMAGES (TAB F) The total cost of damages amounted to PhP383,969,253.22, with PhP128,513,750.00 for infrastructure and PhP255,455,503.22 for agriculture in Regions X, XI and CARAGA. I. SUSPENSION OF CLASSES AND GOVERNMENT OFFICES (as of 21 January 2014) REGION PROVINCE/CITY/MUNICIPALITY REMARKS Preschool, elementary -

Download the 2018 Annual Report

1 Table of CONTENTS 1 LETTER TO THE PRESIDENT 2 THE TREASURER’S REPORT 4 ASSET MANAGEMENT 7 LIABILITY MANAGEMENT 13 NATIONAL GOVERNMENT ACCOUNTING 14 REGIONAL OPERATIONS 16 SUPPORT SERVICES 19 ORGANIZATIONAL CHART 20 DIRECTORY OF OFFICIALS 2 LETTER TO THE PRESIDENT June 28, 2019 PRESIDENT RODRIGO ROA DUTERTE Republic of the Philippines Malacañang, Manila Dear Mr. President: It is my honor to present the Annual Report of the Bureau of the Treasury for the year 2018. The report features the Bureau’s significant contributions through various reforms and programs in exercising its mandate of prudently and proactively managing the Government’s financial resources. On behalf of the officials and employees of the Bureau, I would like to take this opportunity to thank the President for the support and trust in our pursuit of fiscal management objectives. Rest assured that the Bureau will uphold its mandate of fiscal efficiency and sustainability, contributing towards shared economic prosperity. Very truly yours, ROSALIA V. DE LEON Treasurer of the Philippines 1 3 THE TREASURER’S REPORT 2018 was a proving ground for the soundness of the plans and initiatives we have put in place to actively administer Government resources and prudently manage public debt. Amidst the unraveling of a challenging financial environment, we were able to respond to the Government’s expanding financing need head-on through proper cash management and a strategic approach to fundraising. As part of our stewardship over government resources, we endeavored to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of our financial asset management including maximizing returns on the investible funds of the Government. -

Chapter 5 Improved Infrastructure and Logistics Support

Chapter 5 Improved Infrastructure and Logistics Support I. REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES Davao Region still needs to improve its infrastructure facilities and services. While the Davao International Airport has been recently completed, road infrastructure, seaport, and telecommunication facilities need to be upgraded. Flood control and similar structures are needed in flood prone areas while power and water supply facilities are still lacking in the region’s remote and underserved areas. While the region is pushing for increased production of staple crops, irrigation support facilities in major agricultural production areas are still inadequate. Off-site infrastructure in designated tourism and agri-industrial areas are likewise needed to encourage investment and spur economic activities. Accessibility and Mobility through Transport There is a need for the construction of new roads and improvement of the existing road network to provide better access and linkage within and outside the Region as an alternate to existing arterial and local roads. The lack of good roads in the interior parts of the municipalities and provinces connecting to major arterial roads constrains the growth of agriculture and industry in the Region; it also limits the operations of transport services due to high maintenance cost and longer turnaround time. Traffic congestion is likewise becoming a problem in highly urbanized and urbanizing areas like Davao City and Tagum City. While the Region is physically connected with the adjoining regions in Mindanao, poor road condition in some major highways also hampers inter-regional economic activities. The expansion of agricultural activities in the resettlement and key production areas necessitates the opening and construction of alternative routes and farm-to-market roads. -

Japan Chr Nicles Mindanao 1

SPECIAL ISSUE 2020 Japan Chr nicles Mindanao 1 CONTENTS Message from the Consul General 2 Linking Japan to Mindanao Activities of the Japanese Government in Davao and Mindanao 3 Japanese Culture 5-6 Special Feature: Japan’s COVID-19 Response 7 Japan’s Efforts in battling COVID-19 in the Philippines 9 COVID-19 stories and experiences 10-11 The Consulate General of Japan and the Davao Japanese Community in action 11 About Us The first Japanese Consulate in Davao was established in the year 1920. The Japanese Consulate was set up to look after the welfare of the Japanese settlers in Davao whose population grew to 20,000 in 1941. It was during this time that Davao came to be known as “Little Tokyo”. After the diplomatic relations between the Philippines and Japandevelopment were normalized projects and in 1956,people-to-people Japan has contributedexchanges. Into the growth of Philippines and Mindanao through various 1974, the Consular Office of Japan in Davao was reopened. Onupgraded January status 1, 2019, is a concretethe Consular proof office of the was commitment transformed of to a full-fledged Consulate General of Japan in Davao. The Japanese Consulate in Davao, 1920 Photo courtesy of IMIN – The Philippine-Japan Japan by putting a premium on its relationship with Davao Historical Museum in Calinan, Davao City City, Mindanao and, the Philippines, as a whole. Cover Photo: Ibaraki Prefecture Consulate General of Japan in Davao, 2020 Cropped photo of “Oarai Isosaki Shrine - Kamiiso Torii gate and Sunrise” ©SQZ (Licensed under CC BY 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Message from the Consul General 2 The Consulate General of Japan in Davao is pleased to present you with the first “Japan Chronicles Mindanao” magazine which we are publishing to promote Japan in the field of culture, food, tourism as well as to give updates on Mindanao-Japan relations. -

Minimum Wage Order No. RB XII-16

Republic of the Philippines Department of Labor and Employment National Wages and Productivity Commission REGIONAL TRIPARTITE WAGES AND PRODUCTIVITY BOARD Region XII, Koronadal City WAGE ORDER NO. RB XII-16 PROVIDING FOR NEW MINIMUM WAGE RATES IN REGION XII WHEREAS, under R.A. No. 6727, otherwise known as the Wage Rationalization Act, the Regional Tripartite Wages and Productivity Board - Region XII (RTWPB XII), is mandated to periodically assess the wage rates, and to conduct continuing studies in the determination of the minimum wage rates applicable in the region; WHEREAS , considering that Wage Order No. RB XII-15 was issued two (2) years ago and there being no petition, the RTWPB XII has resolved to review, motu proprio, the existing minimum wage rates in the region; WHEREAS, the RTWPB XII, after giving due notices to all concerned sectors, conducted public consultations/public hearings on September 2 and 3, 2010 in General Santos City and Kidapawan City, respectively; to determine the propriety of issuing a new wage order; WHEREAS , the results of the studies on the socio-economic conditions of the region, public consultations/public hearings, and deliberations revealed that there is the need to grant an increase in the minimum wage rates of workers in the private sector in Region XII; WHEREAS , consistent with the government’s policy of achieving higher levels of productivity to preserve and generate jobs and to augment the income of workers, there is a need to build the capacity of business enterprises to be competitive through productivity improvement programs; NOW THEREFORE, by virtue of the power and authority vested under Republic Act No.