The Hasidic “Cell”. the Organization of Hasidic Groups at the Level of the Community*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chassidus on the Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) VA’ES CHA NAN _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah Deciphered Messages The Torah tells us ( Shemos 19:19) that when the Jewish people gathered at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah , “Moshe spoke and Hashem answered him with a voice.” The Gemora (Berochos 45a) der ives from this pasuk the principle that that an interpreter should not speak more loudly than the reader whose words he is translating. Tosafos immediately ask the obvious question: from that pasuk we see actually see the opposite: that the reader should n ot speak more loudly than the interpreter. We know, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, that Moshe’s nevua (prophecy) was different from that of the other nevi’im (prophets) in that “the Shechina was speaking through Moshe’s throat”. This means that the interpretation of the nevuos of the other nevi’im is not dependent on the comprehension of the people who hear it. The nevua arrives in this world in the mind of the novi and passes through the filter of his perspectives. The resulting message is the essence of the nevua. When Moshe prophesied, however, it was as if the Shechina spoke from his throat directly to all the people on their particular level of understanding. Consequently, his nevuos were directly accessible to all people. In this sense then, Moshe was the rea der of the nevua , and Hashem was the interpreter. -

Lelov: Cultural Memory and a Jewish Town in Poland. Investigating the Identity and History of an Ultra - Orthodox Society

Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Item Type Thesis Authors Morawska, Lucja Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 03/10/2021 19:09:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/7827 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Lucja MORAWSKA Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and International Studies University of Bradford 2012 i Lucja Morawska Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Key words: Chasidism, Jewish History in Eastern Europe, Biederman family, Chasidic pilgrimage, Poland, Lelov Abstract. Lelov, an otherwise quiet village about fifty miles south of Cracow (Poland), is where Rebbe Dovid (David) Biederman founder of the Lelov ultra-orthodox (Chasidic) Jewish group, - is buried. -

Mattos Chassidus on the Massei ~ Mattos Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) MATTOS ~ MASSEI _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah – Mattos Keep Your Word The Torah states (30:3), “If a man takes a vow or swears an oath to G -d to establish a prohibition upon himself, he shall not violate his word; he shall fulfill whatever comes out of his mouth.” In relation to this passuk , the Midrash quotes from Tehillim (144:4), “Our days are like a fleeting shadow.” What is the connection? This can be explained, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, according to a Gemara ( Nedarim 10b), which states, “It is forbidden to say, ‘ Lashem korban , for G-d − an offering.’ Instead a person must say, ‘ Korban Lashem , an offering for G -d.’ Why? Because he may die before he says the word korban , and then he will have said the holy Name in vain.” In this light, we can understand the Midrash. The Torah states that a person makes “a vow to G-d.” This i s the exact language that must be used, mentioning the vow first. Why? Because “our days are like a fleeting shadow,” and there is always the possibility that he may die before he finishes his vow and he will have uttered the Name in vain. n Story The wood chopper had come to Ryczywohl from the nearby village in which he lived, hoping to find some kind of employment. -

Women and Hasidism: a “Non-Sectarian” Perspective

Jewish History (2013) 27: 399–434 © The Author(s) 2013. This article is published DOI: 10.1007/s10835-013-9190-x with open access at Springerlink.com Women and Hasidism: A “Non-Sectarian” Perspective MARCIN WODZINSKI´ University of Wrocław, Wrocław, Poland E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Hasidism has often been defined and viewed as a sect. By implication, if Hasidism was indeed a sect, then membership would have encompassed all the social ties of the “sectari- ans,” including their family ties, thus forcing us to consider their mothers, wives, and daughters as full-fledged female hasidim. In reality, however, women did not become hasidim in their own right, at least not in terms of the categories implied by the definition of Hasidism as a sect. Reconsideration of the logical implications of the identification of Hasidism as a sect leads to a radical re-evaluation of the relationship between the hasidic movement and its female con- stituency, and, by extension, of larger issues concerning the boundaries of Hasidism. Keywords Hasidism · Eastern Europe · Gender · Women · Sectarianism · Family Introduction Beginning with Jewish historiography during the Haskalah period, through Wissenschaft des Judentums, to Dubnow and the national school, scholars have traditionally regarded Hasidism as a sect. This view had its roots in the earliest critiques of Hasidism, first by the mitnagedim and subsequently by the maskilim.1 It attributed to Hasidism the characteristic features of a sect, 1The term kat hahasidim (the sect of hasidim)orkat hamithasedim (the sect of false hasidim or sanctimonious hypocrites) appears often in the anti-hasidic polemics of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. -

Fine Judaica

t K ESTENBAUM FINE JUDAICA . & C PRINTED BOOKS, MANUSCRIPTS, GRAPHIC & CEREMONIAL ART OMPANY F INE J UDAICA : P RINTED B OOKS , M ANUSCRIPTS , G RAPHIC & C & EREMONIAL A RT • T HURSDAY , N OVEMBER 12 TH , 2020 K ESTENBAUM & C OMPANY THURSDAY, NOV EMBER 12TH 2020 K ESTENBAUM & C OMPANY . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art Lot 115 Catalogue of FINE JUDAICA . Printed Books, Manuscripts, Graphic & Ceremonial Art Featuring Distinguished Chassidic & Rabbinic Autograph Letters ❧ Significant Americana from the Collection of a Gentleman, including Colonial-era Manuscripts ❧ To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 12th November, 2020 at 1:00 pm precisely This auction will be conducted only via online bidding through Bidspirit or Live Auctioneers, and by pre-arranged telephone or absentee bids. See our website to register (mandatory). Exhibition is by Appointment ONLY. This Sale may be referred to as: “Shinov” Sale Number Ninety-One . KESTENBAUM & COMPANY The Brooklyn Navy Yard Building 77, Suite 1108 141 Flushing Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11205 Tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 www.Kestenbaum.net K ESTENBAUM & C OMPANY . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager: Zushye L.J. Kestenbaum Client Relations: Sandra E. Rapoport, Esq. Judaica & Hebraica: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Shimon Steinmetz (consultant) Fine Musical Instruments (Specialist): David Bonsey Israel Office: Massye H. Kestenbaum ❧ Order of Sale Manuscripts: Lot 1-17 Autograph Letters: Lot 18 - 112 American-Judaica: Lot 113 - 143 Printed Books: Lot 144 - 194 Graphic Art: Lot 195-210 Ceremonial Objects: Lot 211 - End of Sale Front Cover Illustration: See Lot 96 Back Cover Illustration: See Lot 4 List of prices realized will be posted on our website following the sale www.kestenbaum.net — M ANUSCRIPTS — 1 (BIBLE). -

USHMM Finding

https://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection Interviewee: ETKOWICZ, Tess Date: May 22, 2008 Interviewer: Patricia Rich Audio tapes: 2 English Transcript: 1 vol. (unpaged) English Audio Record #: GC00118 Libr. Catlg. #: D 810.J4 G7 #196 Restrictions: None SUMMARY Tess Etkowicz, nee Erman, was born in Lublin, Poland on September 19, 1924, the youngest of 6 children from a well-to-do family. The family lived in Lodz, Poland from in 1927-28. Before the war her father was a sales representative in textiles. She describes pre-war Poland including her education, synagogue life, and antisemitism and her fright (at 15) at the German invasion (1939) when she worried about family members in Warsaw. She witnessed cruelty by German soldiers and describes how Polish teens came to their apartment and took artwork and her piano. Her family then fled to Warsaw (where they rented an apartment) until the area became part of the ghetto. Both she and one sister passed as Polish (since they were blond and spoke fluent Polish) and were thus able to smuggle extra food into the Warsaw Ghetto. In 1942, Tess and her sister fled the ghetto, and hid in the county. Tess soon decided to go back and smuggle her parents out. She describes conditions in the Lublin Ghetto: deportation of men, illness, and describes the horrible conditions in the hospital which she witnessed when she contracted typhus. She describes in detail how she smuggled her parents out of the ghetto passing as Poles (wearing shawls, scarfs and caps) and on a train to the small village where she had stayed before. -

Tzadik Righteous One", Pl

Tzadik righteous one", pl. tzadikim [tsadi" , צדיק :Tzadik/Zadik/Sadiq [tsaˈdik] (Hebrew ,ṣadiqim) is a title in Judaism given to people considered righteous צדיקים [kimˈ such as Biblical figures and later spiritual masters. The root of the word ṣadiq, is ṣ-d- tzedek), which means "justice" or "righteousness". The feminine term for a צדק) q righteous person is tzadeikes/tzaddeket. Tzadik is also the root of the word tzedakah ('charity', literally 'righteousness'). The term tzadik "righteous", and its associated meanings, developed in Rabbinic thought from its Talmudic contrast with hasid ("pious" honorific), to its exploration in Ethical literature, and its esoteric spiritualisation in Kabbalah. Since the late 17th century, in Hasidic Judaism, the institution of the mystical tzadik as a divine channel assumed central importance, combining popularization of (hands- on) Jewish mysticism with social movement for the first time.[1] Adapting former Kabbalistic theosophical terminology, Hasidic thought internalised mystical Joseph interprets Pharaoh's Dream experience, emphasising deveikut attachment to its Rebbe leadership, who embody (Genesis 41:15–41). Of the Biblical and channel the Divine flow of blessing to the world.[2] figures in Judaism, Yosef is customarily called the Tzadik. Where the Patriarchs lived supernally as shepherds, the quality of righteousness contrasts most in Contents Joseph's holiness amidst foreign worldliness. In Kabbalah, Joseph Etymology embodies the Sephirah of Yesod, The nature of the Tzadik the lower descending -

Retlof Organization Exempt Froiicome

Form 9 9 0 RetLof Organization Exempt Froiicome Tax Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung Department of the Treasury benefit trust or private foundation) Internal Revenue Service ► The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. A i-or ine zuu4 calenaar ear or tax year De mnm u i i Luna anu enam ub ju Zuu5 B Check If epppeahle please C Name of organization D Employer identification number Address -Iris Chong. JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND 23-7174183 label or Name change print or Number and street (or P.O box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Initial retun typ e. See Final return Specific 575 MADISON AVENUE 703 (212)752-8277 Amended Inj„` rehcn City or town, state or country, and ZIP + 4 "n:ma.'° Cash X Accrual Bono. O Apndl,plon NY 1 0022 1 Otherspectfy) 10, • Section 501 ( c)(3) organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable H and I a re not applicable to section 527 organizations trusts must attach a completed Schedule A ( Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates? ❑ Yes a No G Website: ► W . JEWISHCOMMUNALFUND . ORG H(b) If "Yes," enter number of affiliates IN, J Organization type (check only one) ► X 501(c) (03 ) A (Insert no) 4947(a)(1) or 527 H(c) A. all affiliates included? Yes �No (If "No," attach a list See instnichons K Check here ► it the organization' s gross receipts are normally not more than $25,000 The H(d) Is this a separate return filed by an organizati on need not file a retu rn with the IRS, but if the organization received a Form 990 Package organization covered by e group ruling ? Yes X No in the ma il, it should file a return without financial data Some states requi re a complete retu rn. -

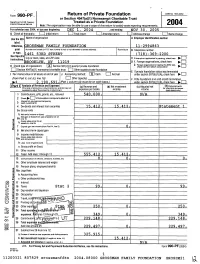

Form 990-PF . Return of Private Foundation

OM B No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF . Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Depart ment of thS Treasu ry Treated as a Private Foundation nterna IRavenue service Note: The organization may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. 2nn4 For calendar year 2004 , or tax year beginning DEC^ 1, 2004 , and ending NOV 3 0, 2005 R r.hpek all that annlu [1 Initial rabirn I I F in al return Amended return F__-1 Addrn nhnn F__I fJnm rhon Name of organization Use the IRS A Employer identification number label. Otherwise , ROSSMAN FAMILY FOUNDATION 11-2994863 print Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/style B Telephone number ortype. 1461 53RD STREET 718 -369-2200 See Specific Ci or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application Is pending , check here ►O Instructions . ty BROOKLYN, NY 11219 D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ►0 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, ►O H Check typea of organization: Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation check here and attach computation 0 Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation E If private foun dation status was terminate d I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ►� (from Part ll, col. (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F It the foundation is in a 60-month termination 111104 2 19 0 6 91 . -

~A Selective List of Books You May Find Useful in Your Research~ United

~A selective list of books you may find useful in your research~ United States 976.602 OK46EMA 1997-1998 Memorial book 979.402 SA14JG, 1997-1999 Nizkor: a publication of the Sacramento Jewish Genealogical Society 979.7 N657JH, 1999-2000 Nizkor = Let us remember 977.302 H752B 2001 Yizkor book of remembrance Europe 947 B17B Bibliography of Eastern European memorial (yizkor) books: with call numbers for six Judaica libraries in New York 929.102 J55FO Jewish memorial (yizkor) books in the United Kingdom: destroyed European Jewish communities Austria 943.602 D489K �ehilat Tsehlim �a-�akhameha Belarus 947.6502 AN88A Antopol: Antipolye: sefer-yizkor 947.6502 B23B Baranovits : sefer zikaron 947.6502 B119B V.1 Bobroysk: sefer zikaron li-kehilat Bobroysk u-venoteha = yizker-bukh far Bobroysker kehileh un umgegnt 947.6502 K799SA Book of Kobrin : the scroll of life and destruction 940.5472 B755BU Brest-Litovsk : encyclopedia of the Jewish diaspora (Belarus) 947.6502 B755BA Bris�-de-Li�a 940.5472 D835SC Drohitchin memorial (yizkor) book: 500 years of Jewish life (Drohiczyn, Belarus) 940.5472 SH699FI Fifty-first brigade : the history of the Jewish partisan group from the Slonim Ghetto 947.6502 H858G Grodnah = Grodne 947.6502 SH295H �urban �ehilat Shetsotsin (Byalis�) 947.6502 L619SA In the partisans' region 947.6502 B471K �ar�uz-Berezeh 947.6502 K841W �orelits-�oreli�sh 940.5472 L53L Life and destruction of Olshan 947.6502 N859CO Memorial (yizkor) book of the Jewish community of Novogrudok, Poland 947.6502 M667M Mins�, ʻir �a-em, �orot, maʻa�im, ishim, -

F Ine J Udaica

F INE J UDAICA . PRINTED BOOKS, AUTOGRAPHED LETTERS, MANUSCRIPTS AND CEREMONIAL &GRAPHIC ART K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 8TH, 2005 K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art Lot 7 Catalogue of F INE J UDAICA . PRINTED BOOKS, AUTOGRAPHED LETTERS, MANUSCRIPTS AND CEREMONIAL &GRAPHIC ART From the Collection of Daniel M. Friedenberg, Greenwich, Conn. To be Offered for Sale by Auction on Tuesday, 8th February, 2005 at 2:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand on Sunday, 6th February: 10:00 am–5:30 pm Monday, 7th February: 10:00 am–6:00 pm Tuesday, 8th February: 10:00 am–1:30 pm Important Notice: A Digital Image of Many Lots Offered in This Sale is Available Upon Request This Sale may be referred to as “Highgate” Sale Number Twenty Seven. Illustrated Catalogues: $35 • $42 (Overseas) KESTENBAUM & COMPANY Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 12 West 27th Street, 13th Floor, New York, NY 10001 • Tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 E-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web Site: www.Kestenbaum.net K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager : Margaret M. Williams Client Accounts: S. Rivka Morris Press & Public Relations: Jackie Insel Printed Books: Rabbi Bezalel Naor Manuscripts & Autographed Letters: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Ceremonial Art: Aviva J. Hoch (Consultant) Catalogue Art Director & Photographer: Anthony Leonardo Auctioneer: Harmer F. Johnson (NYCDCA License no. 0691878) ❧ ❧ ❧ For all inquiries relating to this sale please contact: Daniel E. Kestenbaum ❧ ❧ ❧ ORDER OF SALE Printed Books: Lots 1 – 222 Autographed Letters & Manuscripts: Lots 223 - 363 Ceremonial Arts: Lots 364 - End of Sale A list of prices realized will be posted on our Web site, www.kestenbaum.net, following the sale. -

For Radomsko

PROJECT of “YIDDELE’ MEMORY” FOR RADOMSKO “From Remembrance to Living Memory : RADOMSKO, 1st Jewish open sky Museum in Poland” Young Children of Holocaust Survivors’ Organization Rachel Lea Kesselman, President-Founder “Yiddele’ Memory” 73, Bd Grosso, 06000 Nice, France N° Préfecture W062002980, association loi 1901 à but non lucratif e-mail : [email protected] / www.yiddele-memory.org Letter from the Mayor of Radomsko, Anna Milczanowska Letter from the Regional Prefect (Starosta), Robert Zakrzewski Y’M with Ambassador of Poland in Argentina, Jacek Bazanski, May 2012 Letter of recommendation of Ambassador Jacek Bazanski for “Yiddele’ Memory”s Project in Radomsko Letter from Mr Martin Gray, First Honorary Member of « Yiddele’ Memory » Author of “For those I loved” Letter from Professeur of University : Benjamin GROSS, Israel Letter from Daisy Miller, Director at « Shoah Foundation » Los Angeles Radomsko Héraldique Drapeau Administration Pays Pologne Région Łódź District Radomszczański Maire Anna Milczanowska Code postal 97-500 Indicatif téléphonique international +(48) Indicatif téléphonique local 44 Immatriculation ERA Démographie Population 50 399 hab. (2008) Densité 2 980 hab./km Géographie 51° 04′ 00″ Nord Coordonnées 19° 27′ 00″ Est 51.066667, 19.45 Altitude Min. 220 m — Max. 254 m Superficie 5 142 ha = 51,42 km Twin towns — Sister Cities Makó (Hongrie) Voznesensk (Ukraine) Kiriat Bialik (Israël) Radomsko is a city in Poland with 50 399 inhabitants (at 16 April 2008). It is a chief town of the district (powiat) of Łódź. Location Radomsko is 90 km south of Łódź, on the Radomka River. The city is crossed by important communication channels: National Highway 1 (future highway) and the Warsaw-Vienna railway line.