El Juego Real De Cupido: a Spanish Board Game Published in Antwerp, C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December-2016.Pdf

the hollstein journal december 2016 It is my great pleasure to write these first few lines introducing our first e-newsletter. Via this medium, which we aim to publish at least twice a year, we will keep you informed about various Hollstein projects: more in depth information about some of our current projects, new research, publication schedules, as well as other activities connected to Dutch and Flemish and German prints before 1700. In this first issue you will be introduced by Ad Stijnman to Johannes Teyler and the à la poupée printing technique. These volumes to be published in our series The New Hollstein Dutch & Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts, 1450-1700 will be the first ever to be in full colour. Some of our previous volumes on the oeuvres of Hendrick Goltzius and Frans Floris already included a few colour plates but Teyler’s substantial oeuvre covers every colour of the rainbow. Marjolein Leesberg will discuss Gerard and Cornelis de Jode. Her research on the De Jode dynasty resulted in such a wealth of new material that we decided to divide The New Hollstein Dutch & Flemish volumes into two separate publications. The first will cover Gerard and Cornelis de Jode and the second following comprises the subsequent family members Pieter de Jode I, Pieter de Jode II, and Arnold de Jode. With the end of the year quickly approaching, I, on behalf of the whole team, would like to take the opportunity to wish you a Merry Christmas and a prosperous 2017. Frits Garritsen Director johannes teyler and dutch colour printing 1685-1710 The group of prints compiled for the forthcoming The à la poupée process had been used since 1457,2 New Hollstein volumes concern what are known as usually inking copper plates but also woodblocks in ‘Teyler prints’. -

Reference Resources for Cataloguing German and Low Countries Imprints to Ca. 1800

Geleitwort Wer sich mit der Ermittlung, der Katalogisierung oder dem bibliographischen Nachweis Alter Drucke befasst, benötigt eine breite Palette der unterschiedlichsten Hilfsmittel. Da, wo noch keine modernen Standardreferenzwerke vorliegen, ist der Rückgriff auf ältere, zeitnahe oder zeitgenössische Werke oft unverzichtbar. Im Rahmen seiner langjährigen Tätigkeit an der National Library of Scotland hat sich Dr. William A. Kelly intensiv mit der retrospektiven Bibliographie der deutschen und der niederländischen Druckschriften beschäftigt und über viele Jahre hinweg auf diesem Gebiet ein beinahe konkurrenzloses Expertenwissen erworben. Es ehrt ihn, dass er diese Kenntnisse von Anfang an mit anderen, bibliothekarischen Kollegen zumal, teilen wollte. Ursprünglich war „nur“ an eine Ergänzung eines bereits 1982 eingeführten Hilfsmittels gedacht – der Standard Citation Forms of published bibliographies and catalogues used in rare book cataloging nämlich. Angesichts der umfassenden Kenntnisse und der Gründlichkeit des Bearbeiters zeigte sich jedoch rasch, dass das Supplement für den deutschen und niederländischen Bereich den Umfang des gesamten Hauptwerks um ein vielfaches übertreffen würde: In seinem verdienstvollen Verzeichnis weist Dr. Kelly fast 2.150 einschlägige (bio-)bibliographische Nachschlagewerke nach. Da ein derart hoch-spezialisiertes Werk jedoch naturgemäß nur einen sehr eingeschränkten Käuferkreis findet, mochte – trotz großer inhaltlicher Wertschätzung - kein Verleger das unternehmerische Risiko einer kommerziellen Publikation -

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton Hawley III Jamaica Plain, MA M.A., History of Art, Institute of Fine Arts – New York University, 2010 B.A., Art History and History, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art and Architectural History University of Virginia May, 2015 _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Life of Cornelis Visscher .......................................................................................... 3 Early Life and Family .................................................................................................................... 4 Artistic Training and Guild Membership ...................................................................................... 9 Move to Amsterdam ................................................................................................................. -

2012 Annual Progress Report and 2013 Program Plan of the Gemini Observatory

2012 Annual Progress Report and 2013 Program Plan of the Gemini Observatory Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc. Table of Contents 0 Executive Summary ....................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction and Overview .............................................................................. 5 2 Science Highlights ........................................................................................... 6 2.1 Highest Resolution Optical Images of Pluto from the Ground ...................... 6 2.2 Dynamical Measurements of Extremely Massive Black Holes ...................... 6 2.3 The Best Standard Candle for Cosmology ...................................................... 7 2.4 Beginning to Solve the Cooling Flow Problem ............................................... 8 2.5 A Disappearing Dusty Disk .............................................................................. 9 2.6 Gas Morphology and Kinematics of Sub-Millimeter Galaxies........................ 9 2.7 No Intermediate-Mass Black Hole at the Center of M71 ............................... 10 3 Operations ...................................................................................................... 11 3.1 Gemini Publications and User Relationships ............................................... 11 3.2 Science Operations ........................................................................................ 12 3.2.1 ITAC Software and Queue Filling Results .................................................. -

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Baseline Studies

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Baseline Studies July – September 2009 Quarterly Report Geo-Marine, Inc. 2201 K Avenue, Suite A2 Plano, Texas 75074 October 5, 2009 New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Baseline Studies July-September 2009 Quarterly Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................................ iv LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS........................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................... 1 1.0 QUALITY ASSURANCE WORK PLAN........................................................................................... 1 2.0 LITERATURE REVIEW.................................................................................................................... 1 3.0 DIGITAL DATA COMPILATION...................................................................................................... 2 4.0 AVIAN PREDICTIVE/PROBABILITY MODEL ................................................................................ 2 5.0 BASELINE SURVEYS .................................................................................................................... -

Open Access Version Via Utrecht University Repository

Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka 3930424 March 2018 Master Thesis Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context University of Utrecht Prof. dr. M.A. Weststeijn Prof. dr. E. Manikowska 1 Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Index Introduction p. 4 Historiography and research motivation p. 4 Theoretical framework p. 12 Research question p. 15 Chapters summary and methodology p. 15 1. The collection of Stanisław August 1.1. Introduction p. 18 1.1.1. Catalogues p. 19 1.1.2. Residences p. 22 1.2. Netherlandish painting in the collection in general p. 26 1.2.1. General remarks p. 26 1.2.2. Genres p. 28 1.2.3. Netherlandish painting in the collection per stylistic schools p. 30 1.2.3.1. The circle of Rubens and Van Dyck p. 30 1.2.3.2. The circle of Rembrandt p. 33 1.2.3.3. Italianate landscapists p. 41 1.2.3.4. Fijnschilders p. 44 1.2.3.5. Other Netherlandish artists p. 47 1.3. Other painting schools in the collection p. 52 1.3.1. Paintings by court painters in Warsaw p. 52 1.3.2. Italian paintings p. 53 1.3.3. French paintings p. 54 1.3.4. German paintings p. -

MASTER DRAWINGS Index to Volumes 1–55 1963–2017 Compiled by Maria Oldal [email protected]

MASTER DRAWINGS Index to Volumes 1–55 1963–2017 Compiled by Maria Oldal [email protected] The subject of articles or notes is printed in CAPITAL letters; book and exhibition catalogue titles are given in italics; volume numbers are in Roman numerals and in bold face. Included in individual artist entries are authentic works, studio works, copies, attributions, etc., arranged in sequential order within the citations for each volume. When an author has written reviews, that designation appears at the end of the review citations. Names of collectors are in italics. Abbreviated names of Italian churches are alphabetized as if fully spelled out: "Rome, S. <San> Pietro in Montorio" precedes "S. <Santa> Maria del Popolo." Concordance of Master Drawings volumes and year of publication: I 1963 XII 1974 XXIII–XXIV 1985–86 XXXV 1997 XLVI 2008 II 1964 XIII 1975 XXV 1987 XXXVI 1998 XLVII 2009 III 1965 XIV 1976 XXVI 1988 XXXVII 1999 XLVIII 2010 IV 1966 XV 1977 XXVII 1989 XXXVIII 2000 XLIX 2011 V 1967 XVI 1978 XXVIII 1990 XXXIX 2001 L 2012 VI 1968 XVII 1979 XXIX 1991 XL 2002 LI 2013 VII 1969 XVIII 1980 XXX 1992 XLI 2003 LII 2014 VIII 1970 XIX 1981 XXXI 1993 XLII 2004 LIII 2015 IX 1971 XX 1982 XXXII 1994 XLIII 2005 LIV 2016 X 1972 XXI 1983 XXXIII 1995 XLIV 2006 LV 2017 XI 1973 XXII 1984 XXXIV 1996 XLV 2007 À l’ombre des frondaisons d’Arcueil: Dessiner un jardin du XVIIe siècle, exh. cat. by Xavier Salmon et al. Review. LIV: 397–404 A. S. -

Figures for the Soul

FIGURES FOR THE SOUL ELIZABETH DWYER BARRINGER-LINDNER FELLOW FIGURES FOR THE SOUL ELIZABETH DWYER BARRINGER-LINDNER FELLOW Front Cover (left to right): Albrecht Dürer German, 1471-1528 The Scourging of Christ (The Flagellation of Christ) from the Engraved Passion series (1507-1512), 1512 Engraving, 4 9/16 x 3 in. (11.59 x 7.62 cm) Museum Purchase with Curriculum Support Funds, 1982.5 Hendrick Goltzius, Dutch, 1558 – 1617 Pietà, 1596 Engraving, 7 1/2 x 5 1/8 in. (19.05 x 13.02 cm) (sheet) Museum Purchase with Curriculum Support Funds, 1988.28 The Fralin Museum of Art’s programming is made possible by the generous support of The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation. The exhibition is also made possible through generous support of the Arts$, the Suzanne Foley Endowment Fund, WTJU 91.1 FM albemarle Magazine, and Ivy Publications LLC’s Charlottesville Welcome Book. CATALOGUE ROTATION I Figures for the Soul “Among all the paintings here, PRINTS BY those by Dürer interest me the most…[his] are figures which ALBRECHT DÜRER remain in the soul.” Of the many who have praised Albrecht Dürer Arranged chronologically, the following — Johann Gottfried von Herder, 1788 (1471–1528), none so eloquently capture the works chart his evolving technique from the aesthetic of his work as von Herder. Today rudimentary design of early woodcuts to esteemed as the premier artist of the Northern the refined modulation of late engravings. Renaissance and the father of German Art, Among the Museum’s stunning examples Dürer mastered painting, drawing, watercolor, are twinned prints from two of his most cel- art theory, and mathematics. -

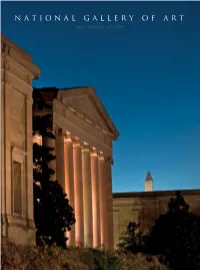

NGA | 2012 Annual Report

NA TIO NAL G AL LER Y O F A R T 2012 ANNUAL REPort 1 ART & EDUCATION Diana Bracco BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEE Vincent J. Buonanno (as of 30 September 2012) Victoria P. Sant W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Chairman Calvin Cafritz Earl A. Powell III Leo A. Daly III Frederick W. Beinecke Barney A. Ebsworth Mitchell P. Rales Gregory W. Fazakerley Sharon P. Rockefeller Doris Fisher John Wilmerding Juliet C. Folger Marina Kellen French FINANCE COMMITTEE Morton Funger Mitchell P. Rales Lenore Greenberg Chairman Frederic C. Hamilton Timothy F. Geithner Richard C. Hedreen Secretary of the Treasury Teresa Heinz Frederick W. Beinecke John Wilmerding Victoria P. Sant Helen Henderson Sharon P. Rockefeller Chairman President Benjamin R. Jacobs Victoria P. Sant Sheila C. Johnson John Wilmerding Betsy K. Karel Linda H. Kaufman AUDIT COMMITTEE Robert L. Kirk Frederick W. Beinecke Leonard A. Lauder Chairman LaSalle D. Leffall Jr. Timothy F. Geithner Secretary of the Treasury Edward J. Mathias Mitchell P. Rales Diane A. Nixon John G. Pappajohn Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Mitchell P. Rales Victoria P. Sant Sally E. Pingree John Wilmerding Diana C. Prince Robert M. Rosenthal TRUSTEES EMERITI Roger W. Sant Robert F. Erburu Andrew M. Saul John C. Fontaine Thomas A. Saunders III Julian Ganz, Jr. Fern M. Schad Alexander M. Laughlin Albert H. Small David O. Maxwell Michelle Smith Ruth Carter Stevenson Benjamin F. Stapleton Luther M. Stovall Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Roberts Jr. EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Ladislaus von Hoffmann Chief Justice of the Diana Walker United States Victoria P. Sant President Alice L. -

'Daar Doet Het Rijk Ceylon Haar Milde Schatkist Open'

‘Daar doet het rijk Ceylon haar milde schatkist open’ De VOC en de invloed van koloniale exploitatie op de natuurlijke omgeving in Ceylon (1662-1785) Carlijn van der Baan 10645381 Begeleider Dr. D. H. van Netten Masterscriptie Geschiedenis Universiteit van Amsterdam 11-07-2017 ‘Daar doet het rijk Ceylon haar milde schatkist open, En komt my minzaam door de wond’re kragten nopen, Dieze in de schorsen der Caneelboom heeft gebaard, Om al den glorie van haar heerelijken aart Te zingen, dat het lang den Naneef dreunt in de oren: Geen vrugt van Libanon kan zo den mensch bekoren, Of kragten geven aan het afgeloogt gemoed, Als hier dit eyland door Kaneelgeur rijkelijk doet: Laat dan vry Vrankrijk met haar Safferanen pralen, En ’t moedig Duytsland op haar Lelien der dalen Het hoofd opbeuren, heel hoveerdig op die bloem, Zy wijken billijk voor de herelijke roem Van ’t Zalig eyland, wiens vergulde en rijke stander, Is in het groot geweld der wakk’re Nederlander: Het gunt ons overvloed van waren, ja kaneel Zo geestverquiquikkend, dat de Koningen, hoe eêl, Genoegen vinden, als zy dese fijnste geuren, Gebroken naar de kunst in hare spijs bespeuren.’1 1 G. van Kervel, Opkomst, Magt en Heerlykheyt van het Oostindisch-Huys der Stadt Rotterdam (Den Haag 1701) 22. 2 3 Abstract Ceylon (nowadays Sri Lanka) was made during the Dutch period into a profitable colony. The Dutch East India Company traded here mainly in cinnamon, pepper and elephants. By means of surveyors and mapmakers the Company was able to perpetuate their colonial governance and explore new trading opportunities. -

Marian Piety and the Forging of the Community in Hendrick Goltzius's the Life of the Virgin Elissa Auerbach

Marian Studies Volume 60 Telling Mary's Story: The "Life of Mary" Article 13 Through the Ages 2009 Marian Piety and the Forging of the Community in Hendrick Goltzius's the Life of the Virgin Elissa Auerbach Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Auerbach, Elissa (2009) "Marian Piety and the Forging of the Community in Hendrick Goltzius's the Life of the Virgin," Marian Studies: Vol. 60, Article 13. Available at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies/vol60/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Studies by an authorized editor of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Auerbach: Marian Piety and Goltzius's Life of the Virgin MAruA.N PIETY AND THE FoRGING OF CoMMUNITY IN HENDRICK GoLTZIUs's THE LIFE OF THE ViRGIN Elissa Auerbach, Ph.D.* Introduction On May 29, 1578, riotous Dutch Calvinist soldiers entered Haarlem's St. Bavo Cathedral during the holy feast-day cele bration of Corpus Christi where they incited a scene of complete bedlam.1 Brandishing swords and shouting at wor shippers, the soldiers killed a priest and plundered the church, thus bringing a decisive end to the Catholic ownership of the cathedral. Throughout the summer, Calvinists removed from the church the works of art and liturgical objects that were most offensive to them, and in September the Reformed Church officially reconsecrated the building as the Grote Kerk (Great Church). -

Źródła Alberti Leon Battista, O Malarstwie, Oprac. M. Rzepińska

Źródła Alberti Leon Battista, O malarstwie, oprac. M. Rzepińska, tłum. L. Winniczuk, Wrocław–Warszawa– Kraków 1963. Aldrich K., Fehl Ph., Fehl R., The literature of classical art: Franciscus Junius, (I) The Painting of the Ancients, (II) A Lexicon of Artists and their Works, Berkeley 1991. Ampzing Samuel, Beschrijvinge ende Lof der Stadt Haerlem in Hollant, Amsterdam 1974 (reprint wydania Haarlem 1628). Armenini Giovanni Battista, De’ veri precetti della Pittura, oprac. M. Gorreri, Torino 1988. Baldinucci Filippo, Notizie de’ professori del disegno, (Firenze 1681), [w:] Opere, t. 10, Milano 1812. Bembo Pietro, Prose della volgar lingua (1513) i De imitazione (ok. 1513) [w:] Prosatori latini del Quattrocento, red. E. Garin, (Classici italiani, 13), Milano-Napoli 1952, s. 903–905 Białostocki J., Myśliciele, kronikarze i artyści o sztuce od starożytności do 1500 r., Warszawa 1978. Białostocki J., Teoretycy, pisarze i artyści o sztuce 1500–1600, Warszawa 1985. Białostocki J., Poprzęcka M., Ziemba A., Teoretycy, historiografowie i artyści o sztuce 1600–1700, Warszawa 1994. Braun Georg, Hogenberg Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum, wyd. facs., oprac. M. Schefold, I–VI, Stuttgart 1965–1970. Bray Salomon de, Architectura moderna, ofte Bouwinge van onsen tyt, Amsterdam 1631 (reprint: Soest 1971). Bredius A., Künstler-Inventare. Urkunden zur Geschichte der holländischen Kunst des XVIten, XVIIten und XVIIIten Jahrhunderts, t. 1–8, Haag 1915–1922. Brom G., Langeraad L.A. van, Diarium van Arend van Buchell, Amsterdam 1907. Campen J.W.C. van, Aernout van Buchell: Notae Quotidianae, Utrecht 1940. Cellini Benvenuto, Sopra l’arte del disegno, [w:] P. Barocchi, Scritti d’arte del Cinquecento, Milano- Napoli 1971–1977. Deutschland vor drei Jahrhunderten.