Democratic Backsliding Through Electoral Irregularities: the Case of Venezuela

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Room for Debate the National Constituent Assembly and the Crumbling of the Rule of Law in Venezuela

No Room for Debate The National Constituent Assembly and the Crumbling of the Rule of Law in Venezuela July 2019 Composed of 60 eminent judges and lawyers from all regions of the world, the International Commission of Jurists promotes and protects human rights through the Rule of Law, by using its unique legal expertise to develop and strengthen national and international justice systems. Established in 1952 and active on the five continents, the ICJ aims to ensure the progressive development and effective implementation of international human rights and international humanitarian law; secure the realization of civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights; safeguard the separation of powers; and guarantee the independence of the judiciary and legal profession. ® No Room for Debate - The National Constituent Assembly and the Crumbling of the Rule of Law in Venezuela © Copyright International Commission of Jurists Published in July 2019 The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) permits free reproduction of extracts from any of its publications provided that due acknowledgment is given and a copy of the publication carrying the extract is sent to its headquarters at the following address: International Commission of Jurists P.O. Box 91 Rue des Bains 33 Geneva Switzerland No Room for Debate The National Constituent Assembly and the Crumbling of the Rule of Law in Venezuela This report was written by Santiago Martínez Neira, consultant to the International Commission of Jurists. Carlos Ayala, Sam Zarifi and Ian Seiderman provided legal and policy review. This report was written in Spanish and translated to English by Leslie Carmichael. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................... -

Protecting Politics: Deterring the Influence Of

Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Protecting Politics: Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Elections are essential elements of democratic systems. Unfortunately, abuse and manipulation (including voter intimidation, vote buying or ballot stuffing) can distort these processes. However, little attention has been paid to an intrinsic part of this threat: the conditions and opportunities for criminal interference in the electoral process. Most worrying, few scholars have examined the underlying conditions that make elections vulnerable to organized criminal involvement. This report addresses these gaps in knowledge by analysing the vulnerabilities of electoral processes to illicit interference (above all by organized crime). It suggests how national and international authorities might better protect these crucial and coveted elements of the democratic process. Case studies from Georgia, Mali and Mexico illustrate these challenges and provide insights into potential ways to prevent and mitigate the effects of organized crime on elections. International IDEA Clingendael Institute ISBN 978-91-7671-069-2 Strömsborg P.O. Box 93080 SE-103 34 Stockholm 2509 AB The Hague Sweden The Netherlands T +46 8 698 37 00 T +31 70 324 53 84 F +46 8 20 24 22 F +31 70 328 20 02 9 789176 710692 > [email protected] [email protected] www.idea.int www.clingendael.nl ISBN: 978-91-7671-069-2 Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Series editor: Catalina Uribe Burcher Lead authors: Ivan Briscoe and Diana Goff © 2016 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance © 2016 Netherlands Institute of International Relations (Clingendael Institute) International IDEA Strömsborg SE-103 34 Stockholm Sweden Tel: +46 8 698 37 00, fax: +46 8 20 24 22 Email: [email protected], website: www.idea.int Clingendael Institute P.O. -

The Impact of Disinformation on Democratic Processes and Human Rights in the World

STUDY Requested by the DROI subcommittee The impact of disinformation on democratic processes and human rights in the world @Adobe Stock Authors: Carme COLOMINA, Héctor SÁNCHEZ MARGALEF, Richard YOUNGS European Parliament coordinator: Policy Department for External Relations EN Directorate General for External Policies of the Union PE 653.635 - April 2021 DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT STUDY The impact of disinformation on democratic processes and human rights in the world ABSTRACT Around the world, disinformation is spreading and becoming a more complex phenomenon based on emerging techniques of deception. Disinformation undermines human rights and many elements of good quality democracy; but counter-disinformation measures can also have a prejudicial impact on human rights and democracy. COVID-19 compounds both these dynamics and has unleashed more intense waves of disinformation, allied to human rights and democracy setbacks. Effective responses to disinformation are needed at multiple levels, including formal laws and regulations, corporate measures and civil society action. While the EU has begun to tackle disinformation in its external actions, it has scope to place greater stress on the human rights dimension of this challenge. In doing so, the EU can draw upon best practice examples from around the world that tackle disinformation through a human rights lens. This study proposes steps the EU can take to build counter-disinformation more seamlessly into its global human rights and democracy policies. -

Disinformation in Democracies: Strengthening Digital Resilience in Latin America

Atlantic Council ADRIENNE ARSHT LATIN AMERICA CENTER Disinformation in Democracies: Strengthening Digital Resilience in Latin America The Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center broadens understanding of regional transformations through high-impact work that shapes the conversation among policymakers, the business community, and civil society. The Center focuses on Latin America’s strategic role in a global context with a priority on pressing political, economic, and social issues that will define the trajectory of the region now and in the years ahead. Select lines of programming include: Venezuela’s crisis; Mexico-US and global ties; China in Latin America; Colombia’s future; a changing Brazil; Central America’s trajectory; combatting disinformation; shifting trade patterns; and leveraging energy resources. Jason Marczak serves as Center Director. The Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) is at the forefront of open-source reporting and tracking events related to security, democracy, technology, and where each intersect as they occur. A new model of expertise adapted for impact and real-world results, coupled with efforts to build a global community of #DigitalSherlocks and teach public skills to identify and expose attempts to pollute the information space, DFRLab has operationalized the study of disinformation to forge digital resilience as humans are more connected than at any point in history. For more information, please visit www.AtlanticCouncil.org. This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The authors are solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s conclusions. -

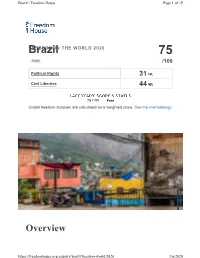

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Brazil | Freedom House Page 1 of 19 BrazilFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 75 FREE /100 Political Rights 31 Civil Liberties 44 75 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Brazil | Freedom House Page 2 of 19 Brazil is a democracy that holds competitive elections, and the political arena is characterized by vibrant public debate. However, independent journalists and civil society activists risk harassment and violent attack, and the government has struggled to address high rates of violent crime and disproportionate violence against and economic exclusion of minorities. Corruption is endemic at top levels, contributing to widespread disillusionment with traditional political parties. Societal discrimination and violence against LGBT+ people remains a serious problem. Key Developments in 2019 • In June, revelations emerged that Justice Minister Sérgio Moro, when he had served as a judge, colluded with federal prosecutors by offered advice on how to handle the corruption case against former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who was convicted of those charges in 2017. The Supreme Court later ruled that defendants could only be imprisoned after all appeals to higher courts had been exhausted, paving the way for Lula’s release from detention in November. • The legislature’s approval of a major pension reform in the fall marked a victory for Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was inaugurated in January after winning the 2018 election. It also signaled a return to the business of governing, following a period in which the executive and legislative branches were preoccupied with major corruption scandals and an impeachment process. -

CRACKDOWN on DISSENT Brutality, Torture, and Political Persecution in Venezuela

CRACKDOWN ON DISSENT Brutality, Torture, and Political Persecution in Venezuela HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Crackdown on Dissent Brutality, Torture, and Political Persecution in Venezuela Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-35492 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit: http://www.hrw.org The Foro Penal (FP) or Penal Forum is a Venezuelan NGO that has worked defending human rights since 2002, offering free assistance to victims of state repression, including those arbitrarily detained, tortured, or murdered. The Penal Forum currently has a network of 200 volunteer lawyers and more than 4,000 volunteer activists, with regional representatives throughout Venezuela and also in other countries such as Argentina, Chile, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Uruguay, and the USA. Volunteers provide assistance and free legal counsel to victims, and organize campaigns for the release of political prisoners, to stop state repression, and increase the political and social cost for the Venezuelan government to use repression as a mechanism to stay in power. -

THE CHAVEZ Pages

Third World Quarterly, Vol 24, No 1, pp 63–76, 2003 The Chávez phenomenon: political change in Venezuela RONALD D SYLVIA & CONSTANTINE P DANOPOULOS ABSTRACT This article focuses on the advent and governing style of, and issues facing colonel-turned politician Hugo Chávez since he became president of Venezuela in 1998 with 58% of the vote. The article begins with a brief account of the nature of the country’s political environment that emerged in 1958, following the demise of the Perez Jimenez dictatorship. Aided by phenomenal increases in oil prices, Venezuela’s political elites reached a pact that governed the country for nearly four decades. Huge increases in education, health and other social services constituted the hallmark of Venezuela’s ‘subsidised democracy’. Pervasive corruption, a decrease in oil revenues and two abortive coups in 1992 challenged the foundations of subsidised democracy. The election of Chávez in 1998 sealed the fate of the 1958 pact. Chávez’s charisma, anti- colonial/Bolivarist rhetoric, and increasing levels of poverty form the basis of his support among the poor and dissatisfied middle classes. The articles then turns its attention to Chávez’s governing style and the problems he faces as he labours to turn around the country’s stagnant economy. Populist initiatives aimed at wealth redistribution, land reform and a more multidimensional and Third World-orientated foreign policy form the main tenets of the Chávez regime. These, coupled with anti-business rhetoric, over-dependence on oil revenues and opposition from Venezuela’s political and economic elites, have polarised the country and threaten its political stability. -

Rudy Giuliani Lawyer Says Smartmatic Smears Were “Product Disparagement” Not Full-Out Defamation – Update

PRINT Rudy Giuliani Lawyer Says Smartmatic Smears Were “Product Disparagement” Not Full-Out Defamation – Update By Jill Goldsmith August 17, 2021 12:34pm Jill Goldsmith Co-Business Editor More Stories By Jill Rudy Giuliani Lawyer Says Smartmatic Smears Were “Product Disparagement” Not Full-Out Defamation – Update CNN’s Clarissa Ward On “Watching History Unfold” In Afghanistan ViacomCBS Sells Black Rock Building In Midtown Manhattan To Harbor Group For $760 Million VIEW ALL Rudy Giuliani AP Photo/John Minchillo Rudy Giuliani’s attorney rehashed conspiracy theories and was light on evidence when pressed by a judge Tuesday in a defamation suit brought by voting software firm Smartmatic. Joe Sibley of Camara & Sibley asked New York State Supreme Court Judge David Cohen to dismiss six of the claims against his client Giuliani because they constituted “product disparagement,” or calling the software lousy, not defamation. The latter is the charge brought by the company in a lawsuit against Fox, three of its hosts, Giuliani and Sidney Powell. Defendants have asked for the case to be dismissed and their counsel, one by one, had the chance at a long hearing today to say why, followed by rebuttals by Smartmatic’s team. Cohen asked Sibley about one of the Trump attorney’s claims — that, in Venezuela, Smartmatic “’switched votes around subtly, maybe ten percent per district, so you don’t notice it.’ Is there some support in that to show that they can’t even make out a claim for actual malice?” he asked. Here’s Sibley’s response and some of the exchange: Sibley: “I believe in the declaration there’s some discussion of how they did it, that they kind of skimmed votes here and there to flip the votes.” Cohen: “What about Mr. -

Venezuela: Background and U.S

Venezuela: Background and U.S. Relations Updated June 4, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44841 Venezuela: Background and U.S. Relations Summary Venezuela remains in a deep political and economic crisis under the authoritarian rule of Nicolás Maduro of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela. Maduro, narrowly elected in 2013 after the death of Hugo Chávez (president, 1999-2013), began a second term on January 10, 2019, that most Venezuelans and much of the international community consider illegitimate. Since January, Juan Guaidó, president of Venezuela’s democratically elected, opposition-controlled National Assembly, has sought to form an interim government to serve until internationally observed elections can be held. Although the United States and 53 other countries recognize Guaidó as interim president, the military high command, supported by Russia and Cuba, has remained loyal to Maduro. Venezuela is in a political stalemate as conditions in the country deteriorate. Venezuela’s economy has collapsed. It is plagued by hyperinflation, severe shortages of food and medicine, and electricity blackouts that have worsened an already dire humanitarian crisis. In April 2019, United Nations officials estimated that some 90% of Venezuelans are living in poverty and 7 million need humanitarian assistance. Maduro has blamed U.S. sanctions for these problems, but most observers cite economic mismanagement and corruption under Chávez and Maduro for the current crisis. U.N. agencies estimate that 3.7 million Venezuelans had fled the country as of March 2019, primarily to other Latin American and Caribbean countries. U.S. Policy The United States historically had close relations with Venezuela, a major U.S. -

Venezuela: Issues for Congress, 2013-2016

Venezuela: Issues for Congress, 2013-2016 Mark P. Sullivan Specialist in Latin American Affairs January 23, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43239 Venezuela: Issues for Congress, 2013-2016 Summary Although historically the United States had close relations with Venezuela, a major oil supplier, friction in bilateral relations increased under the leftist, populist government of President Hugo Chávez (1999-2013), who died in 2013 after battling cancer. After Chávez’s death, Venezuela held presidential elections in which acting President Nicolás Maduro narrowly defeated Henrique Capriles of the opposition Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD), with the opposition alleging significant irregularities. In 2014, the Maduro government violently suppressed protests and imprisoned a major opposition figure, Leopoldo López, along with others. In December 2015, the MUD initially won a two-thirds supermajority in National Assembly elections, a major defeat for the ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). The Maduro government subsequently thwarted the legislature’s power by preventing three MUD representatives from taking office (denying the opposition a supermajority) and using the Supreme Court to block bills approved by the legislature. For much of 2016, opposition efforts were focused on recalling President Maduro through a national referendum, but the government slowed down the referendum process and suspended it indefinitely in October. After an appeal by Pope Francis, the government and most of the opposition (with the exception of Leopoldo López’s Popular Will party) agreed to talks mediated by the Vatican along with the former presidents of the Dominican Republic, Spain, and Panama and the head of the Union of South American Nations. -

Proof of Publication

Case 20-33332-KLP Doc 911 Filed 02/11/21 Entered 02/11/21 10:37:51 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 2 PROOF OF PUBLICATION 21 ___________________________Feb-10, 20___ /͕ĚŐĂƌEŽďůĞƐĂůĂ͕ŝŶŵLJĐĂƉĂĐŝƚLJĂƐĂWƌŝŶĐŝƉĂůůĞƌŬŽĨƚŚĞWƵďůŝƐŚĞƌŽĨ Ă ĚĂŝůLJŶĞǁƐƉĂƉĞƌŽĨŐĞŶĞƌĂůĐŝƌĐƵůĂƚŝŽŶƉƌŝŶƚĞĚĂŶĚƉƵďůŝƐŚĞĚŝŶƚŚĞŝƚLJ͕ŽƵŶƚLJĂŶĚ^ƚĂƚĞŽĨEĞǁzŽƌŬ͕ ŚĞƌĞďLJĐĞƌƚŝĨLJƚŚĂƚƚŚĞĂĚǀĞƌƚŝƐĞŵĞŶƚĂŶŶĞdžĞĚŚĞƌĞƚŽǁĂƐƉƵďůŝƐŚĞĚŝŶƚŚĞĞĚŝƚŝŽŶƐŽĨ ŽŶƚŚĞĨŽůůŽǁŝŶŐĚĂƚĞŽƌĚĂƚĞƐ͕ƚŽǁŝƚŽŶ Feb 10, 2021, NYT & Natl, pg B3 ͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺ ͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺ ^ǁŽƌŶƚŽŵĞƚŚŝƐϭϬƚŚĚĂLJŽĨ &ĞďƌƵĂƌLJ͕ϮϬϮϭ ͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺͺ EŽƚĂƌLJWƵďůŝĐ Case 20-33332-KLP Doc 911 Filed 02/11/21 Entered 02/11/21 10:37:51 Desc Main C M Y K Nxxx,2021-02-10,B,003,Bs-BW,E1Document Page 2 of 2 THE NEW YORK TIMES BUSINESS WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 10, 2021 N B3 MEDIA Reddit Raises Fox Seeks to Dismiss Election Lawsuit Times Places $250 Million, By MICHAEL M. GRYNBAUM A Top Editor and JONAH E. BROMWICH Pushing Value Rupert Murdoch’s Fox Corpora- In the Office tion filed a motion on Monday to To $6 Billion dismiss the $2.7 billion defamation Of Its Publisher lawsuit brought against it last By MIKE ISAAC week by the election technology By MARC TRACY company Smartmatic, which has SAN FRANCISCO — Fresh off a win- The New York Times announced accused Mr. Murdoch’s cable net- ning Super Bowl ad and a role at on Tuesday that one of its highest- works and three Fox anchors of the center of a recent stock mar- ranking editors, Rebecca Blumen- spreading falsehoods that the stein, will take on a newly created ket frenzy, Reddit announced on company tried to rig the presiden- role, reporting directly to the pub- Monday that it had raised $250 tial race against Donald J. Trump. lisher, A. -

Democracy Index 2020 in Sickness and in Health?

Democracy Index 2020 In sickness and in health? A report by The Economist Intelligence Unit www.eiu.com The world leader in global business intelligence The Economist Intelligence Unit (The EIU) is the research and analysis division of The Economist Group, the sister company to The Economist newspaper. Created in 1946, we have over 70 years’ experience in helping businesses, financial firms and governments to understand how the world is changing and how that creates opportunities to be seized and risks to be managed. Given that many of the issues facing the world have an international (if not global) dimension, The EIU is ideally positioned to be commentator, interpreter and forecaster on the phenomenon of globalisation as it gathers pace and impact. EIU subscription services The world’s leading organisations rely on our subscription services for data, analysis and forecasts to keep them informed about what is happening around the world. We specialise in: • Country Analysis: Access to regular, detailed country-specific economic and political forecasts, as well as assessments of the business and regulatory environments in different markets. • Risk Analysis: Our risk services identify actual and potential threats around the world and help our clients understand the implications for their organisations. • Industry Analysis: Five year forecasts, analysis of key themes and news analysis for six key industries in 60 major economies. These forecasts are based on the latest data and in-depth analysis of industry trends. EIU Consulting EIU Consulting is a bespoke service designed to provide solutions specific to our customers’ needs. We specialise in these key sectors: • Healthcare: Together with our two specialised consultancies, Bazian and Clearstate, The EIU helps healthcare organisations build and maintain successful and sustainable businesses across the healthcare ecosystem.