A Combinatorial Approach for Constructing Lattice Structures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit 6 Visualising Solid Shapes(Final)

• 3D shapes/objects are those which do not lie completely in a plane. • 3D objects have different views from different positions. • A solid is a polyhedron if it is made up of only polygonal faces, the faces meet at edges which are line segments and the edges meet at a point called vertex. • Euler’s formula for any polyhedron is, F + V – E = 2 Where F stands for number of faces, V for number of vertices and E for number of edges. • Types of polyhedrons: (a) Convex polyhedron A convex polyhedron is one in which all faces make it convex. e.g. (1) (2) (3) (4) 12/04/18 (1) and (2) are convex polyhedrons whereas (3) and (4) are non convex polyhedron. (b) Regular polyhedra or platonic solids: A polyhedron is regular if its faces are congruent regular polygons and the same number of faces meet at each vertex. For example, a cube is a platonic solid because all six of its faces are congruent squares. There are five such solids– tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron and icosahedron. e.g. • A prism is a polyhedron whose bottom and top faces (known as bases) are congruent polygons and faces known as lateral faces are parallelograms (when the side faces are rectangles, the shape is known as right prism). • A pyramid is a polyhedron whose base is a polygon and lateral faces are triangles. • A map depicts the location of a particular object/place in relation to other objects/places. The front, top and side of a figure are shown. Use centimetre cubes to build the figure. -

Convex Polytopes and Tilings with Few Flag Orbits

Convex Polytopes and Tilings with Few Flag Orbits by Nicholas Matteo B.A. in Mathematics, Miami University M.A. in Mathematics, Miami University A dissertation submitted to The Faculty of the College of Science of Northeastern University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 14, 2015 Dissertation directed by Egon Schulte Professor of Mathematics Abstract of Dissertation The amount of symmetry possessed by a convex polytope, or a tiling by convex polytopes, is reflected by the number of orbits of its flags under the action of the Euclidean isometries preserving the polytope. The convex polytopes with only one flag orbit have been classified since the work of Schläfli in the 19th century. In this dissertation, convex polytopes with up to three flag orbits are classified. Two-orbit convex polytopes exist only in two or three dimensions, and the only ones whose combinatorial automorphism group is also two-orbit are the cuboctahedron, the icosidodecahedron, the rhombic dodecahedron, and the rhombic triacontahedron. Two-orbit face-to-face tilings by convex polytopes exist on E1, E2, and E3; the only ones which are also combinatorially two-orbit are the trihexagonal plane tiling, the rhombille plane tiling, the tetrahedral-octahedral honeycomb, and the rhombic dodecahedral honeycomb. Moreover, any combinatorially two-orbit convex polytope or tiling is isomorphic to one on the above list. Three-orbit convex polytopes exist in two through eight dimensions. There are infinitely many in three dimensions, including prisms over regular polygons, truncated Platonic solids, and their dual bipyramids and Kleetopes. There are infinitely many in four dimensions, comprising the rectified regular 4-polytopes, the p; p-duoprisms, the bitruncated 4-simplex, the bitruncated 24-cell, and their duals. -

Step 1: 3D Shapes

Year 1 – Autumn Block 3 – Shape Step 1: 3D Shapes © Classroom Secrets Limited 2018 Introduction Match the shape to its correct name. A. B. C. D. E. cylinder square- cuboid cube sphere based pyramid © Classroom Secrets Limited 2018 Introduction Match the shape to its correct name. A. B. C. D. E. cube sphere square- cylinder cuboid based pyramid © Classroom Secrets Limited 2018 Varied Fluency 1 True or false? The shape below is a cone. © Classroom Secrets Limited 2018 Varied Fluency 1 True or false? The shape below is a cone. False, the shape is a triangular-based pyramid. © Classroom Secrets Limited 2018 Varied Fluency 2 Circle the correct name of the shape below. cylinder pyramid cuboid © Classroom Secrets Limited 2018 Varied Fluency 2 Circle the correct name of the shape below. cylinder pyramid cuboid © Classroom Secrets Limited 2018 Varied Fluency 3 Which shape is the odd one out? © Classroom Secrets Limited 2018 Varied Fluency 3 Which shape is the odd one out? The cuboid is the odd one out because the other shapes are cylinders. © Classroom Secrets Limited 2018 Varied Fluency 4 Follow the path of the cuboids to make it through the maze. Start © Classroom Secrets Limited 2018 Varied Fluency 4 Follow the path of the cuboids to make it through the maze. Start © Classroom Secrets Limited 2018 Reasoning 1 The shapes below are labelled. Spot the mistake. A. B. C. cone cuboid cube Explain your answer. © Classroom Secrets Limited 2018 Reasoning 1 The shapes below are labelled. Spot the mistake. A. B. C. cone cuboid cube Explain your answer. -

A Method for Predicting Multivariate Random Loads and a Discrete Approximation of the Multidimensional Design Load Envelope

International Forum on Aeroelasticity and Structural Dynamics IFASD 2017 25-28 June 2017 Como, Italy A METHOD FOR PREDICTING MULTIVARIATE RANDOM LOADS AND A DISCRETE APPROXIMATION OF THE MULTIDIMENSIONAL DESIGN LOAD ENVELOPE Carlo Aquilini1 and Daniele Parisse1 1Airbus Defence and Space GmbH Rechliner Str., 85077 Manching, Germany [email protected] Keywords: aeroelasticity, buffeting, combined random loads, multidimensional design load envelope, IFASD-2017 Abstract: Random loads are of greatest concern during the design phase of new aircraft. They can either result from a stationary Gaussian process, such as continuous turbulence, or from a random process, such as buffet. Buffet phenomena are especially relevant for fighters flying in the transonic regime at high angles of attack or when the turbulent, separated air flow induces fluctuating pressures on structures like wing surfaces, horizontal tail planes, vertical tail planes, airbrakes, flaps or landing gear doors. In this paper a method is presented for predicting n-dimensional combined loads in the presence of massively separated flows. This method can be used both early in the design process, when only numerical data are available, and later, when test data measurements have been performed. Moreover, the two-dimensional load envelope for combined load cases and its discretization, which are well documented in the literature, are generalized to n dimensions, n ≥ 3. 1 INTRODUCTION The main objectives of this paper are: 1. To derive a method for predicting multivariate loads (but also displacements, velocities and accelerations in terms of auto- and cross-power spectra, [1, pp. 319-320]) for aircraft, or parts of them, subjected to a random excitation. -

Optimization of Tensegrity Lattice with Truncated Octahedral Units

OptimizationM. Ohsaki, J. Y. of Zhang, tensegrity K. Kogiso lattice andwith J. truncated J. Rimoli octahedral units Proceedings of the IASS Annual Symposium 2019 – Structural Membranes 2019 Form and Force 7 – 10 October 2019, Barcelona, Spain C. Lázaro, K.-U. Bletzinger, E. Oñate (eds.) Optimization of tensegrity lattice with truncated octahedral units Makoto OHSAKI∗a, Jingyao ZHANGa, Kosuke KOGISOa, Julian J. RIMOLIc *aDepartment of Architecture and Architectural Engineering, Kyoto University Kyoto-Daigaku Katsura, Nishikyo, Kyoto 615-8540, Japan [email protected] b School of Aerospace Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA 30332, USA Abstract An optimization method is presented for tensegrity lattices composed of eight truncated octahedral units. The stored strain energy under specified forced vertical displacement is maximized under constraint on the structural material volume. The nonlinear behavior of bars allowing buckling is modeled as a bi- linear elastic material. As a result of optimization, a flexible structure with degrading vertical stiffness is obtained to be applicable to an energy absorption device or a vertical isolation system. Keywords: tensegrity, optimization, strain energy, truncated octahedral unit 1. Introduction Tensegrity structures are a class of self-standing pin jointed structures consisting of thin bars (struts) and cables stiffened by applying prestresses to their members [1, 3]. Because the bars are not continuously connected, i.e., they are topologically isolated from each other, these structures are usually too flexible to be used as load-resisting components of structures in mechanical and civil engineering applications. However, by exploiting their flexibility, tensegrity structures can be utilized as devices for reducing impact forces, isolating dynamic forces, and absorbing energy, to name a few applications [5]. -

19. Three-Dimensional Figures

19. Three-Dimensional Figures Exercise 19A 1. Question Write down the number of faces of each of the following figures: A. Cuboid B. Cube C. Triangular prism D. Square pyramid E. Tetrahedron Answer A. 6 Face is also known as sides. A Cuboid has six faces. Book, Matchbox, Brick etc. are examples of Cuboid. B.6 A Cube has six faces and all faces are equal in length. Sugar Cubes, Dice etc. are examples of Cube. C. 5 A Triangular prism has two triangular faces and three rectangular faces. D. 5 A Square pyramid has one square face as a base and four triangular faces as the sides. So, Square pyramid has total five faces. E. 4 A Tetrahedron (Triangular Pyramid) has one triangular face as a base and three triangular faces as the sides. So, Tetrahedron has total four faces. 2. Question Write down the number of edges of each of the following figures: A. Tetrahedron B. Rectangular pyramid C. Cube D. Triangular prism Answer A. 6 A Tetrahedron has six edges. OA, OB, OC, AB, AC, BC are the 6 edges. B. 8 A Rectangular Pyramid has eight edges. AB, BC, CD, DA, OA, OB, DC, OD are the 8 edges. C. 12 A Cube has twelve edges. AB, BC, CD, DA, EF, FG, GH, HE, AE, DH, BF, CG are the edges. D. 9 A Triangular prism has nine edges. AB, BC, CA, DE, EF, FD, AD, BE, CF are the9 edges. 3. Question Write down the number of vertices of each of the following figures: A. -

1 Introduction

Kumamoto J.Math. Vol.23 (2010), 49-61 Minimal Surface Area Related to Kelvin's Conjecture 1 Jin-ichi Itoh and Chie Nara 2 (Received March 2, 2009) Abstract How can a space be divided into cells of equal volume so as to minimize the surface area of the boundary? L. Kelvin conjectured that the partition made by a tiling (packing) of congruent copies of the truncated octahedron with slightly curved faces is the solution ([4]). In 1994, D. Phelan and R. Weaire [6] showed a counterexample to Kelvin's conjecture, whose tiling consists of two kinds of cells with curved faces. In this paper, we study the orthic version of Kelvin's conjecture: the truncated octahedron has the minimum surface area among all polyhedral space-fillers, where a polyhedron is called a space-filler if its congruent copies fill space with no gaps and no overlaps. We study the new conjecture by restricting a family of space- fillers to its subfamily consisting of unfoldings of doubly covered cuboids (rectangular parallelepipeds), we show that the truncated octahedron has the minimum surfacep parea among all polyhedral unfoldings of a doubly covered cuboid with relation 2 : 2 : 1 for its edge lengths. We also give the minimum surface area of polyhedral unfoldings of a doubly covered cube. 1 Introduction. The problem of foams, first raised by L. Kelvin, is easy to state and hard to solve ([4]). How can space be divided into cells of equal volume so as to minimize the surface area of the boundary? Kelvin conjectured that the partition made by a tiling (packing) of congruent copies of the truncated octahedron with slightly curved faces is the solution. -

Design and Analysis of Honeycomb Structures With

DESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF HONEYCOMB STRUCTURES WITH ADVANCED CELL WALLS A Dissertation by RUOSHUI WANG Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Xinghang Zhang Co-Chair of Committee, Jyhwen Wang Committee Members, Amine Benzerga Karl 'Ted' Hartwig Head of Department, Ibrahim Karaman December 2016 Major Subject: Materials Science and Engineering Copyright 2016 Ruoshui Wang ABSTRACT Honeycomb structures are widely used in engineering applications. This work consists of three parts, in which three modified honeycombs are designed and analyzed. The objectives are to obtain honeycomb structures with improved specific stiffness and specific buckling resistance while considering the manufacturing feasibility. The objective of the first part is to develop analytical models for general case honeycombs with non-linear cell walls. Using spline curve functions, the model can describe a wide range of 2-D periodic structures with nonlinear cell walls. The derived analytical model is verified by comparing model predictions with other existing models, finite element analysis (FEA) and experimental results. Parametric studies are conducted by analytical calculation and finite element modeling to investigate the influences of the spline waviness on the homogenized properties. It is found that, comparing to straight cell walls, spline cell walls have increased out-of-plane buckling resistance per unit weight, and the extent of such improvement depends on the distribution of the spline’s curvature. The second part of this research proposes a honeycomb with laminated composite cell walls, which offer a wide selection of constituent materials and improved specific stiffness. -

Study on Delaunay Tessellations of 1-Irregular Cuboids for 3D Mixed Element Meshes

Study on Delaunay tessellations of 1-irregular cuboids for 3D mixed element meshes David Contreras and Nancy Hitschfeld-Kahler Department of Computer Science, FCFM, University of Chile, Chile E-mails: dcontrer,[email protected] Abstract Mixed elements meshes based on the modified octree approach con- tain several co-spherical point configurations. While generating Delaunay tessellations to be used together with the finite volume method, it is not necessary to partition them into tetrahedra; co-spherical elements can be used as final elements. This paper presents a study of all co-spherical elements that appear while tessellating a 1-irregular cuboid (cuboid with at most one Steiner point on its edges) with different aspect ratio. Steiner points can be located at any position between the edge endpoints. When Steiner points are located at edge midpoints, 24 co-spherical elements appear while tessellating 1-irregular cubes. By inserting internal faces and edges to these new elements, this numberp is reduced to 13. When 1-irregular cuboids with aspect ratio equal to 2 are tessellated, 10 co- spherical elementsp are required. If 1-irregular cuboids have aspect ratio between 1 and 2, all the tessellations are adequate for the finite volume method. When Steiner points are located at any position, the study was done for a specific Steiner point distribution on a cube. 38 co-spherical elements were required to tessellate all the generated 1-irregular cubes. Statistics about the impact of each new element in the tessellations of 1-irregular cuboids are also included. This study was done by develop- ing an algorithm that construct Delaunay tessellations by starting from a Delaunay tetrahedral mesh built by Qhull. -

Plato's Cube and the Natural Geometry of Fragmentation

Plato’s cube and the natural geometry of fragmentation Gábor Domokosa,b, Douglas J. Jerolmackc,d,1, Ferenc Kune, and János Töröka,f aMTA-BME Morphodynamics Research Group, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Budapest, Hungary; bDepartment of Mechanics, Materials and Structure, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Budapest, Hungary; cDepartment of Earth and Environmental Science, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA; dMechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA; eDepartment of Theoretical Physics, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary; fDepartment of Theoretical Physics, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Budapest, Hungary This manuscript was compiled on April 7, 2020 Plato envisioned Earth’s building blocks as cubes, a shape rarely at “T” junctions (26); and “T” junctions rearrange into ”Y” found in nature. The solar system is littered, however, with distorted junctions (25, 28) to either maximize energy release as cracks polyhedra — shards of rock and ice produced by ubiquitous frag- penetrate the bulk (29–31), or during reopening-healing cycles mentation. We apply the theory of convex mosaics to show that from wetting/drying (32) (Fig.3). Whether in rock, ice or soil, the average geometry of natural 2D fragments, from mud cracks to the fracture mosaics cut into stressed landscapes (Fig.3) form Earth’s tectonic plates, has two attractors: “Platonic” quadrangles pathways for focused fluid flow, dissolution and erosion that and “Voronoi” hexagons. In 3D the Platonic attractor is dominant: further disintegrate these materials (33, 34) and reorganize remarkably, the average shape of natural rock fragments is cuboid. landscape patterns (35, 36). Moreover, fracture patterns in When viewed through the lens of convex mosaics, natural fragments rock determine the initial grain size of sediment supplied to are indeed geometric shadows of Plato’s forms. -

Monsters and Moonshine

Monsters and Moonshine lieven le bruyn 2012 universiteit antwerpen neverendingbooks.org CONTENTS 1. Monsters :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 4 1.1 The Scottish solids..............................4 1.2 The Scottish solids hoax...........................4 1.3 Conway’s M13 game.............................8 1.4 The 15-puzzle groupoid (1/2).........................9 1.5 The 15-puzzle groupoid (2/2)......................... 11 1.6 Conway’s M13-groupoid (1/2)........................ 14 1.7 Mathieu’s blackjack (1/3)........................... 16 1.8 Mathieu’s blackjack (2/3)........................... 18 1.9 Mathieu’s blackjack (3/3)........................... 20 1.10 Conway’s M13 groupoid (2/2)........................ 22 1.11 Olivier Messiaen and Mathieu 12 ....................... 24 1.12 Galois’ last letter............................... 26 1.13 Arnold’s trinities (1/2)............................ 28 1.14 The buckyball symmetries.......................... 32 1.15 Arnold’s trinities (2/2)............................ 37 1.16 Klein’s dessins d’enfants and the buckyball................. 39 1.17 The buckyball curve.............................. 42 1.18 The ”uninteresting” case p = 5 ........................ 45 1.19 Tetra lattices.................................. 46 1.20 Who discovered the Leech lattice (1/2).................... 47 1.21 Who discovered the Leech lattice (2/2).................... 50 1.22 Sporadic simple games............................ 53 1.23 Monstrous frustrations............................ 57 1.24 What does the monster -

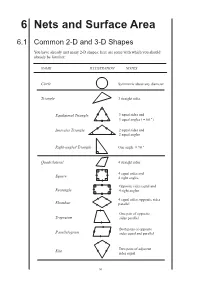

6 Nets and Surface Area

6 Nets and SurfaceMEP Y8 Practice Book A Area 6.1 Common 2-D and 3-D Shapes You have already met many 2-D shapes; here are some with which you should already be familiar: NAME ILLUSTRATION NOTES Circle Symmetric about any diameter Triangle 3 straight sides Equilateral Triangle 3 equal sides and 3 equal angles ( =°60 ) Isosceles Triangle 2 equal sides and 2 equal angles Right-angled Triangle One angle =°90 Quadrilateral 4 straight sides 4 equal sides and Square 4 right angles Opposite sides equal and Rectangle 4 right angles 4 equal sides; opposite sides Rhombus parallel One pair of opposite Trapezium sides parallel Both pairs of opposite Parallelogram sides equal and parallel Two pairs of adjacent Kite sides equal 94 MEP Y8 Practice Book A NAME ILLUSTRATION NOTES Pentagon 5 sides (equal if regular) Hexagon 6 sides (equal if regular) Octagon 8 sides (equal if regular) There are also several 3-D shapes with which you should be familiar: All side lengths equal Cube (square faces), and all angles right angles Faces are combination of Cuboid rectangles (and squares); all angles right angles Cylinder Circular base All points on surface Sphere equidistant from centre All slant edges are Pyramid equal in length in (square-based) a right pyramid Cross-section remains Prism the same throughout (triangular) Tetrahedron All four faces are triangular Note that a square is a special case of a rectangle, as it satisfies the definition; similarly, both a square and a rectangle are special cases of a parallelogram, etc. 95 6.1 MEP Y8 Practice Book A Example 1 What is the name of the 2-D shape with 4 sides and with opposite angles equal? Solution The shape has to be a parallelogram.