The Hidden Agenda Contraception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preven Emergency Contraceptive

9/1/1998 1 Rx Only PREVENÔ Emergency Contraceptive Kit consisting of Emergency Contraceptive Pills and Pregnancy Test Emergency Contraceptive Pills (Levonorgestrel and Ethinyl Estradiol Tablets, USP) and Pregnancy Test The PREVENÔ Emergency Contraceptive Kit is intended to prevent pregnancy after known or suspected contraceptive failure or unprotected intercourse. Emergency contraceptive pills (like all oral contraceptives) do not protect against infection with HIV (the virus that causes AIDS) and other sexually transmitted diseases. DESCRIPTION The PREVENÔ Emergency Contraceptive Kit consists of a patient information book, a urine pregnancy test and four (4) emergency contraceptive pills (ECPs). The pills in the PREVENÔ Emergency Contraceptive Kit are combination oral contraceptives (COCs) which are used to provide postcoital emergency contraception. Each blue film-coated pill contains 0.25 mg levonorgestrel (18,19-Dinorpregn-4-en-20- yn-3-one, 13-Ethyl-17-hydroxy-, (17a)-(-), a totally synthetic progestogen, and 0.05 mg ethinyl estradiol (19-Nor-17a-pregna-1,3,5, (10)-trien-20-yne-3,17-diol). The inactive ingredients present are polacrilin potassium, lactose, magnesium stearate, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, titanium dioxide, polyethylene glycol, polysorbate 80 and FD&C Blue No.2 Aluminum Lake. MOLECULES TO BE ADDED The Pregnancy Test uses monoclonal antibodies to detect the presence of hCG (Human Chorionic Gonadotropin) in the urine. It is sensitive to 20 – 25 mIU / mL 9/1/1998 2 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY ECPs are not effective if the woman is pregnant; they act primarily by inhibiting ovulation. They may also act by altering tubal transport of sperm and/or ova (thereby inhibiting fertilization), and/or possibly altering the endometrium (thereby inhibiting implantation). -

Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 the Norwegian Prescription Database

LEGEMIDDELSTATISTIKK 2018:2 Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 Tema: Legemidler og eldre The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017 Topic: Drug use in the elderly Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 Tema: Legemidler og eldre The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017 Topic: Drug use in the elderly Christian Berg Hege Salvesen Blix Olaug Fenne Kari Furu Vidar Hjellvik Kari Jansdotter Husabø Irene Litleskare Marit Rønning Solveig Sakshaug Randi Selmer Anne-Johanne Søgaard Sissel Torheim Utgitt av Folkehelseinstituttet/Published by Norwegian Institute of Public Health Område for Helsedata og digitalisering Avdeling for Legemiddelstatistikk Juni 2018 Tittel/Title: Legemiddelstatistikk 2018:2 Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017 Forfattere/Authors: Christian Berg, redaktør/editor Hege Salvesen Blix Olaug Fenne Kari Furu Vidar Hjellvik Kari Jansdotter Husabø Irene Litleskare Marit Rønning Solveig Sakshaug Randi Selmer Anne-Johanne Søgaard Sissel Torheim Acknowledgement: Julie D. W. Johansen (English text) Bestilling/Order: Rapporten kan lastes ned som pdf på Folkehelseinstituttets nettsider: www.fhi.no The report can be downloaded from www.fhi.no Grafisk design omslag: Fete Typer Ombrekking: Houston911 Kontaktinformasjon/Contact information: Folkehelseinstituttet/Norwegian Institute of Public Health Postboks 222 Skøyen N-0213 Oslo Tel: +47 21 07 70 00 ISSN: 1890-9647 ISBN: 978-82-8082-926-9 Sitering/Citation: Berg, C (red), Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 [The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017] Legemiddelstatistikk 2018:2, Oslo, Norge: Folkehelseinstituttet, 2018. Tidligere utgaver / Previous editions: 2008: Reseptregisteret 2004–2007 / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2004–2007 2009: Legemiddelstatistikk 2009:2: Reseptregisteret 2004–2008 / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2004–2008 2010: Legemiddelstatistikk 2010:2: Reseptregisteret 2005–2009. Tema: Vanedannende legemidler / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2005–2009. -

Mycophenolate: OB-GYN Contraception Counseling Referral

Current as of 6/1/2013. This document may not be part of the latest approved REMS. OB/GYN CONTRACEPTION COUNSELING LETTER Reference ID: 3194413 Current as of 6/1/2013. This document may not be part of the latest approved REMS. Letter to Ob/Gyn Contraception Counseling ((Date)) ((Recipient’s Name)) ((Recipient’s Address 1)) ((Recipient’s Address 2)) ((City, State, ZIP)) In reference to: My patient ((Patient’s Name)) Reason for the referral: Contraception counseling Dear Dr ((Recipient’s Last Name)): I am writing to you in reference to the above-named patient who is under my care for ((diagnosis)) and ((insert drug information such as drug name, when patient will begin taking the drug, if treatment has already begun, etc)). This medication contains mycophenolate, which is associated with an increased risk of first trimester pregnancy loss and congenital malformations. It is important that this patient receive contraception counseling about methods that are acceptable for use while taking mycophenolate. Prescribers of mycophenolate participate in the FDA-mandated Mycophenolate REMS (Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy) to ensure that the benefits of mycophenolate outweigh the risks. The following table lists the forms of contraception that are acceptable for use during treatment with mycophenolate. Acceptable Contraception Methods for Females of Reproductive Potential Guide your patients to choose from the following birth control options: Option 1 Intrauterine devices (IUDs) Tubal sterilization Methods to Use Patient’s partner had -

Delaying Menstruation During Holidays. Norethisterone 5Mg Tds

Delaying menstruation during holidays. Norethisterone 5mg tds, started 3 days before the expected menses can be used for the postponement of menstruation and is often prescribed prior to a holiday. The effectiveness of the delay varies between individuals. So what is the problem? A review article in the Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive healthcare ( Mansour 2012) highlighted that owing to the specific structure of norethisterone, it is partly metabolised to ethinyl oestradiol. Chu et al 2007 suggested that a daily dose of norethisterone 5mg tds might be equivalent to taking 20-30mcg combined oral contraceptive pill. Therefore, prescribing therapeutic doses of norethisterone for women with significant risk factors for venous thromboembolism ( VTE) may therefore be inappropriate. Who shouldn’t be given norethisterone? Obese Personal h/o VTE Strong FH of VTE Immobile/wheelchair bound Carriers of thrombophilia Any other condition predisposing to VTE If my patient can’t take norethisterone, what are the alternatives? The metabolism to ethinyl oestradiol occurs with doses of norethisterone 5mg and over and therefore, the concern does not apply to or other progestogens or contraceptive pills containing norethisterone. Mansour suggested Medroxyprogesterone ( MPA ) 10mg three times a day to reduce heavy menstrual bleeding. Dr Sarah Grey (personal communication) recommends 20mg medroxyprogesterone to be taken daily, starting 3 days before the expected onset of menses. However, (MPA) is not licensed for this use and the prescriber should follow the rules of off label prescribing. References Safer prescribing of therapeutic norethisterone for women at risk of venous thromboembolism. Mansour JFPRHC July 2012 Formation of ethinyl oestradiol in women during treatment with norethisterone acetate. -

Vaginal Administration of Contraceptives

Scientia Pharmaceutica Review Vaginal Administration of Contraceptives Esmat Jalalvandi 1,*, Hafez Jafari 2 , Christiani A. Amorim 3 , Denise Freitas Siqueira Petri 4 , Lei Nie 5,* and Amin Shavandi 2,* 1 School of Engineering and Physical Sciences, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh EH14 4AS, UK 2 BioMatter Unit, École Polytechnique de Bruxelles, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Avenue F.D. Roosevelt, 50-CP 165/61, 1050 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] 3 Pôle de Recherche en Gynécologie, Institut de Recherche Expérimentale et Clinique, Université Catholique de Louvain, 1200 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] 4 Fundamental Chemistry Department, Institute of Chemistry, University of São Paulo, Av. Prof. Lineu Prestes 748, São Paulo 05508-000, Brazil; [email protected] 5 College of Life Sciences, Xinyang Normal University, Xinyang 464000, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (E.J.); [email protected] (L.N.); [email protected] (A.S.); Tel.: +32-2-650-3681 (A.S.) Abstract: While contraceptive drugs have enabled many people to decide when they want to have a baby, more than 100 million unintended pregnancies each year in the world may indicate the contraceptive requirement of many people has not been well addressed yet. The vagina is a well- established and practical route for the delivery of various pharmacological molecules, including contraceptives. This review aims to present an overview of different contraceptive methods focusing on the vaginal route of delivery for contraceptives, including current developments, discussing the potentials and limitations of the modern methods, designs, and how well each method performs for delivering the contraceptives and preventing pregnancy. -

Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2013 Adapted from the World Health Organization Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2Nd Edition

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Early Release / Vol. 62 June 14, 2013 U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2013 Adapted from the World Health Organization Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2nd Edition Continuing Education Examination available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/cme/conted.html. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Early Release CONTENTS CONTENTS (Continued) Introduction ............................................................................................................1 Appendix A: Summary Chart of U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Methods ....................................................................................................................2 Contraceptive Use, 2010 .................................................................................. 47 How To Use This Document ...............................................................................3 Appendix B: When To Start Using Specific Contraceptive Summary of Changes from WHO SPR ............................................................4 Methods .............................................................................................................. 55 Contraceptive Method Choice .........................................................................4 Appendix C: Examinations and Tests Needed Before Initiation of Maintaining Updated Guidance ......................................................................4 Contraceptive Methods -

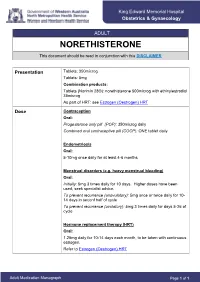

NORETHISTERONE This Document Should Be Read in Conjunction with This DISCLAIMER

King Edward Memorial Hospital Obstetrics & Gynaecology ADULT NORETHISTERONE This document should be read in conjunction with this DISCLAIMER Presentation Tablets: 350microg Tablets: 5mg Combination products: Tablets (Norimin 28®): norethisterone 500microg with ethinylestradiol 35microg As part of HRT: see Estrogen (Oestrogen) HRT Dose Contraception Oral: Progesterone only pill (POP): 350microg daily Combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP): ONE tablet daily Endometriosis Oral: 5-10mg once daily for at least 4-6 months Menstrual disorders (e.g. heavy menstrual bleeding) Oral: Initially: 5mg 3 times daily for 10 days. Higher doses have been used; seek specialist advice. To prevent recurrence (anovulatory): 5mg once or twice daily for 10- 14 days in seconf half of cycle To prevent recurrence (ovulatory): 5mg 3 times daily for days 5-26 of cycle Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) Oral: 1.25mg daily for 10-14 days each month, to be taken with continuous estrogen. Refer to Estrogen (Oestrogen) HRT Adult Medication Monograph Page 1 of 1 Norethisterone – Adult Administration Oral To be taken at the same time each day (or within 3 hours of the usual dose time). For Contraception: Start 4 weeks after the birth of baby (increased risk of abnormal vaginal bleeding if started earlier) Pregnancy 1st Trimester: Contraindicated 2nd Trimester: Contraindicated 3rd Trimester: Contraindicated Breastfeeding Considered safe to use. Progestogens are the preferred hormonal contraceptives as they do not inhibit lactation. Clinical Guidelines Estrogen (Oestrogen) HRT and Policies Progesterone Only Pill Contraception: Post Partum Gynaecology (Non-Oncological) Australian Medicines Handbook. Norethisterone. In: Australian References Medicines Handbook [Internet]. Adelaide (South Australia): Australian Medicines Handbook; 2017 [cited 2017 Apr 12]. -

Variation in Serum Biomarkers with Sex and Female Hormonal Status: Implications for Clinical Tests Received: 11 February 2016 Jordan M

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Variation in serum biomarkers with sex and female hormonal status: implications for clinical tests Received: 11 February 2016 Jordan M. Ramsey1, Jason D. Cooper1, Brenda W. J. H. Penninx2,* & Sabine Bahn1,3,* Accepted: 11 May 2016 Few serum biomarker tests are implemented in clinical practice and recent reports raise concerns Published: 31 May 2016 about poor reproducibility of biomarker studies. Here, we investigated the potential role of sex and female hormonal status in this widespread irreproducibility. We examined 171 serum proteins and small molecules measured in 1,676 participants from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety. Concentrations of 96 molecules varied with sex and 66 molecules varied between oral contraceptive pill users, postmenopausal females, and females in the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle (FDR-adjusted p-value <0.05). Simulations of biomarker studies yielded up to 40% false discoveries when patient and control groups were not matched for sex and up to 41% false discoveries when premenopausal females were not matched for oral contraceptive pill use. High accuracy (over 90%) classification tools were developed to label samples with sex and female hormonal status where this information was not collected. Serum proteomic biomarkers have enormous potential for early diagnosis, quantification of disease risk, prog- nosis, and treatment response prediction and monitoring. They have been investigated for autoimmune dis- ease and arthritis1,2, cancer3–5, cardiovascular disease6, mental and neurological disorders7–12, kidney function13, and other applications. Despite the increasing number of published serum biomarker studies (Supplementary Fig. 1), translation of these findings from the laboratory to clinical tools has proved challenging14,15. -

Contraception in Adolescents – Regulatory Considerations”

“Contraception in adolescents – regulatory considerations” Wissenschaftliche Prüfungsarbeit zur Erlangung des Titels „Master of Drug Regulatory Affairs“ der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn vorgelegt von Dr. Julian Paesler aus Münster Bonn 2016 Betreuerin und 1. Referentin: Frau Dr. Ingrid Klingmann Zweiter Referent: Herr Prof. Dr. Niels Eckstein Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Ingrid Klingmann for her friendly willingness to function as my “supervising tutor” and for the support and the motivating feedback she gave me during the preparation of this master thesis. Her comments and constructive suggestions were very helpful to me. Besides Dr. Ingrid Klingmann, I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Niels Eckstein for his support and the willingness to function as my “secondary tutor”. Special thanks are also due to my mother, who was willing to proofread this master thesis. I am really thankful for all the support she gave - and still gives – to me, which is way more than what could ever be mentioned here. Table of Contents Table of Contents List of Figures .......................................................................................................................... I List of Tables ......................................................................................................................... III List of Abbreviations .............................................................................................................. -

Package Leaflet: Information for the User EVRA 203 Micrograms/24

Package leaflet: Information for the user EVRA 203 micrograms/24 hours + 33.9 micrograms/24 hours transdermal patch norelgestromin/ethinyl estradiol Important things to know about combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs): - They are one of the most reliable reversible methods of contraception if used correctly. - They slightly increase the risk of having a blood clot in the veins and arteries, especially in the first year or when restarting a combined hormonal contraceptive following a break of 4 or more weeks. - Please be alert and see your doctor if you get symptoms of a blood clot (see section 2 “Blood clots”). Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start using this medicine because it contains important information for you. - Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. - If you have any further questions, ask your doctor, pharmacist or nurse. - This medicine has been prescribed for you only. Do not pass it on to others. It may harm them. - If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor, pharmacist or nurse. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. What is in this leaflet 1. What EVRA is and what it is used for 2. What you need to know before you use EVRA 3. How to use EVRA 4. Possible side effects 5. How to store EVRA 6. Contents of the pack and other information 1. What EVRA is and what is it used for EVRA contains two types of sex hormones, a progestogen called norelgestromin and an oestrogen called ethinyl estradiol. -

Emergency Contraception Krishna K

POLICY STATEMENT Organizational Principles to Guide and Define the Child Health Care System and/or Improve the Health of all Children Emergency Contraception Krishna K. Upadhya, MD, MPH, FAAP, COMMITTEE ON ADOLESCENCE Despite significant declines over the past 2 decades, the United States abstract continues to experience birth rates among teenagers that are significantly higher than other high-income nations. Use of emergency contraception (EC) within 120 hours after unprotected or underprotected intercourse can reduce the risk of pregnancy. Emergency contraceptive methods include oral Children’s National Health System, Washington, District of Columbia medications labeled and dedicated for use as EC by the US Food and Drug Policy statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics benefit Administration (ulipristal and levonorgestrel), the “off-label” use of combined from expertise and resources of liaisons and internal (AAP) and external reviewers. However, policy statements from the American oral contraceptives, and insertion of a copper intrauterine device. Indications Academy of Pediatrics may not reflect the views of the liaisons or the for the use of EC include intercourse without use of contraception; condom organizations or government agencies that they represent. breakage or slippage; missed or late doses of contraceptives, including the Dr Upadhya was responsible for all aspects of revising and writing the policy statement with input from reviewers and the Board of Directors; oral contraceptive pill, contraceptive patch, contraceptive ring, and injectable she approves the final manuscript as submitted. contraception; vomiting after use of oral contraceptives; and sexual assault. The guidance in this statement does not indicate an exclusive course Our aim in this updated policy statement is to (1) educate pediatricians and of treatment or serve as a standard of medical care. -

Central and Peripheral Molecular Profiling of Sex Differences in Schizophrenia, Major Depressive Disorder, and Controls

Central and peripheral molecular profiling of sex differences in schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, and controls Jordan Marion Ramsey Churchill College May 2015 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy To my family. Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the support of my supervisor, Prof Sabine Bahn. She provided me with guidance and interesting projects and funded me during the last couple months of my PhD. Her support has been crucial for my PhD work and career development. Most of the funding for my PhD was from the Edmonton Churchill Scholarship. In addition to their generous funding, the encouragement I received from my fellow Edmonton Churchill Scholars during my time here has been invaluable. I would also like to thank the Cambridge Commonwealth Trust for their support. Dr Emanuel Schwarz gave me the first taste for working in this field and helped me through my first research projects on serum molecular sex differences and sex-dependent differences in schizophrenia. His creative take on this work inspired me to keep learning and coming up with new ideas. Dr Jason Cooper took me under his wing and my thesis would not be what it is without his insightful comments and discussions of all chapters in this thesis. I learned an immense amount in a short period with his help and he has helped to shape me as a scientist. He continues to support me and my career, give me confidence in my work, and continuously looks out for my best interests. I cannot thank him enough for that.