Existing and Emerging Shorter-Acting Nondaily Hormonal Contraceptives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preven Emergency Contraceptive

9/1/1998 1 Rx Only PREVENÔ Emergency Contraceptive Kit consisting of Emergency Contraceptive Pills and Pregnancy Test Emergency Contraceptive Pills (Levonorgestrel and Ethinyl Estradiol Tablets, USP) and Pregnancy Test The PREVENÔ Emergency Contraceptive Kit is intended to prevent pregnancy after known or suspected contraceptive failure or unprotected intercourse. Emergency contraceptive pills (like all oral contraceptives) do not protect against infection with HIV (the virus that causes AIDS) and other sexually transmitted diseases. DESCRIPTION The PREVENÔ Emergency Contraceptive Kit consists of a patient information book, a urine pregnancy test and four (4) emergency contraceptive pills (ECPs). The pills in the PREVENÔ Emergency Contraceptive Kit are combination oral contraceptives (COCs) which are used to provide postcoital emergency contraception. Each blue film-coated pill contains 0.25 mg levonorgestrel (18,19-Dinorpregn-4-en-20- yn-3-one, 13-Ethyl-17-hydroxy-, (17a)-(-), a totally synthetic progestogen, and 0.05 mg ethinyl estradiol (19-Nor-17a-pregna-1,3,5, (10)-trien-20-yne-3,17-diol). The inactive ingredients present are polacrilin potassium, lactose, magnesium stearate, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, titanium dioxide, polyethylene glycol, polysorbate 80 and FD&C Blue No.2 Aluminum Lake. MOLECULES TO BE ADDED The Pregnancy Test uses monoclonal antibodies to detect the presence of hCG (Human Chorionic Gonadotropin) in the urine. It is sensitive to 20 – 25 mIU / mL 9/1/1998 2 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY ECPs are not effective if the woman is pregnant; they act primarily by inhibiting ovulation. They may also act by altering tubal transport of sperm and/or ova (thereby inhibiting fertilization), and/or possibly altering the endometrium (thereby inhibiting implantation). -

Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 the Norwegian Prescription Database

LEGEMIDDELSTATISTIKK 2018:2 Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 Tema: Legemidler og eldre The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017 Topic: Drug use in the elderly Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 Tema: Legemidler og eldre The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017 Topic: Drug use in the elderly Christian Berg Hege Salvesen Blix Olaug Fenne Kari Furu Vidar Hjellvik Kari Jansdotter Husabø Irene Litleskare Marit Rønning Solveig Sakshaug Randi Selmer Anne-Johanne Søgaard Sissel Torheim Utgitt av Folkehelseinstituttet/Published by Norwegian Institute of Public Health Område for Helsedata og digitalisering Avdeling for Legemiddelstatistikk Juni 2018 Tittel/Title: Legemiddelstatistikk 2018:2 Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017 Forfattere/Authors: Christian Berg, redaktør/editor Hege Salvesen Blix Olaug Fenne Kari Furu Vidar Hjellvik Kari Jansdotter Husabø Irene Litleskare Marit Rønning Solveig Sakshaug Randi Selmer Anne-Johanne Søgaard Sissel Torheim Acknowledgement: Julie D. W. Johansen (English text) Bestilling/Order: Rapporten kan lastes ned som pdf på Folkehelseinstituttets nettsider: www.fhi.no The report can be downloaded from www.fhi.no Grafisk design omslag: Fete Typer Ombrekking: Houston911 Kontaktinformasjon/Contact information: Folkehelseinstituttet/Norwegian Institute of Public Health Postboks 222 Skøyen N-0213 Oslo Tel: +47 21 07 70 00 ISSN: 1890-9647 ISBN: 978-82-8082-926-9 Sitering/Citation: Berg, C (red), Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 [The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017] Legemiddelstatistikk 2018:2, Oslo, Norge: Folkehelseinstituttet, 2018. Tidligere utgaver / Previous editions: 2008: Reseptregisteret 2004–2007 / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2004–2007 2009: Legemiddelstatistikk 2009:2: Reseptregisteret 2004–2008 / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2004–2008 2010: Legemiddelstatistikk 2010:2: Reseptregisteret 2005–2009. Tema: Vanedannende legemidler / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2005–2009. -

Patch Development with New Drugs Versus Generic Development – Principles and Methods

Patch development with new drugs versus generic development – principles and methods Dr. Barbara Schug SocraTec R&D, Oberursel , Germany www.socratec-pharma.de AGAH Workshop, The new European modified Release Guideline- from cook book to interpretation, Bonn, June 15th –16th, 2015 Some basics Physico-chemical properties / conventional patches small molecule < 500kDa lipophilic potent therapeutic concept which requires low fluctuation Skin controls release rate drug substance dispersed in adhesive matrix Patch controls release rate rate controlling membrane between drug reservoir and skin Currently marketed patches Year Generic (Brand) Names Indication 1979 Scopolamine (Transderm Scop®) Motion sickness 1982 Nitroglycerine (Nitroderm TTS) Angina pectoris 1984 Clonidine (Catapress TTS®) Hypertension 1986 Estradiol (Estraderm®) Menopausal symptoms 1990 Fentanyl (Duragesic®) Chronic pain 1991 Nicotine (Nicoderm®, Habitrol®, Prostep®) Smoking cessation 1993 Testosterone (Androderm®) Testosterone deficiency 1995 Lidocaine/epinephrine (Iontocaine®) Local dermal analgesia 1998 Estradiol/norethindrone (Combipatch®) Menopausal symptoms 1999 Lidocaine (Lidoderm®) Post-herpetic neuralgia pain 2001 Ethinyl estradiol/norelgestromin (OrthoEvra®) Contraception 2003 Estradiol/levonorgestrel (Climara Pro®) Menopause 2003 Oxybutynin (Oxytrol®) Overactive bladder 2004 Lidocaine/ultrasound (SonoPrep®) Local dermal anesthesia Source: modified from Wilson EJ, Three Generations: The Past, Present, and Future of Transdermal Drug Delivery Systems, May 2014 -

F.8 Ethinylestradiol-Etonogestrel.Pdf

General Items 1. Summary statement of the proposal for inclusion, change or deletion. Here within, please find the evidence to support the inclusion Ethinylestradiol/Etonogestrel Vaginal Ring in the World Health Organization’s Essential Medicines List (EML). Unintended pregnancy is regarded as a serious public health issue both in developed and developing countries and has received growing research and policy attention during last few decades (1). It is a major global concern due to its association with adverse physical, mental, social and economic outcomes. Developing countries account for approximately 99% of the global maternal deaths in 2015, with sub-Saharan Africa alone accounting for roughly 66% (2). Even though the incidence of unintended pregnancy has declined globally in the past decade, the rate of unintended pregnancy remains high, particularly in developing regions. (3) Regarding the use of contraceptive vaginal rings, updated bibliography (4,5,6) states that contraceptive vaginal rings (CVR) offer an effective contraceptive option, expanding the available choices of hormonal contraception. Ethinylestradiol/Etonogestrel Vaginal Ring is a non-biodegradable, flexible, transparent with an outer diameter of 54 mm and a cross-sectional diameter of 4 mm. It contains 11.7 mg etonogestrel and 2.7 mg ethinyl estradiol. When placed in the vagina, each ring releases on average 0.120 mg/day of etonogestrel and 0.015 mg/day of ethinyl estradiol over a three-week period of use. Ethinylestradiol/Etonogestrel Vaginal Ring is intended for women of fertile age. The safety and efficacy have been established in women aged 18 to 40 years. The main advantages of CVRs are their effectiveness (similar or slightly better than the pill), ease of use without the need of remembering a daily routine, user ability to control initiation and discontinuation, nearly constant release rate allowing for lower doses, greater bioavailability and good cycle control with the combined ring, in comparison with oral contraceptives. -

Wellness Benefits

Wellness Benefits University of South Alabama This schedule outlines services and items that the University of South Alabama considers a preventive service under this plan. These services must be performed by a physician in the University of South Alabama Health System provider network or by a dermatologist, endocrinologist, durable medical equipment provider, ancillary service provider, urologist, or rheumatologist provider (as applicable) in the entire VIVA HEALTH network. Many of these services are provided as part of an annual physical. This list does not apply to all VIVA HEALTH plans. Please refer to your Summary Plan Description to determine the terms of your health plan. PREVENTIVE SERVICE FREQUENCY/LIMITATIONS Well Baby Visits (Age 0-2) As recommended per guidelines1 Routine screenings, tests, and immunizations As recommended per guidelines Well Child Visits (Age 3-17) One per year at PCP2 Routine screenings, tests, & immunizations As recommended per guidelines HIV screening and counseling As recommended per guidelines Obesity screening As recommended per guidelines Hepatitis B virus screening As recommended per guidelines Sexually transmitted infection counseling Annually Skin cancer behavioral counseling (Beginning at age 10) As recommended per guidelines Routine Physical (Age 18+) One per year at PCP2 Alcohol misuse screening and counseling Annually Blood pressure screening Annually Cholesterol screening As recommended per guidelines Depression screening Annually Diabetes screening As recommended per -

Mycophenolate: OB-GYN Contraception Counseling Referral

Current as of 6/1/2013. This document may not be part of the latest approved REMS. OB/GYN CONTRACEPTION COUNSELING LETTER Reference ID: 3194413 Current as of 6/1/2013. This document may not be part of the latest approved REMS. Letter to Ob/Gyn Contraception Counseling ((Date)) ((Recipient’s Name)) ((Recipient’s Address 1)) ((Recipient’s Address 2)) ((City, State, ZIP)) In reference to: My patient ((Patient’s Name)) Reason for the referral: Contraception counseling Dear Dr ((Recipient’s Last Name)): I am writing to you in reference to the above-named patient who is under my care for ((diagnosis)) and ((insert drug information such as drug name, when patient will begin taking the drug, if treatment has already begun, etc)). This medication contains mycophenolate, which is associated with an increased risk of first trimester pregnancy loss and congenital malformations. It is important that this patient receive contraception counseling about methods that are acceptable for use while taking mycophenolate. Prescribers of mycophenolate participate in the FDA-mandated Mycophenolate REMS (Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy) to ensure that the benefits of mycophenolate outweigh the risks. The following table lists the forms of contraception that are acceptable for use during treatment with mycophenolate. Acceptable Contraception Methods for Females of Reproductive Potential Guide your patients to choose from the following birth control options: Option 1 Intrauterine devices (IUDs) Tubal sterilization Methods to Use Patient’s partner had -

Delaying Menstruation During Holidays. Norethisterone 5Mg Tds

Delaying menstruation during holidays. Norethisterone 5mg tds, started 3 days before the expected menses can be used for the postponement of menstruation and is often prescribed prior to a holiday. The effectiveness of the delay varies between individuals. So what is the problem? A review article in the Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive healthcare ( Mansour 2012) highlighted that owing to the specific structure of norethisterone, it is partly metabolised to ethinyl oestradiol. Chu et al 2007 suggested that a daily dose of norethisterone 5mg tds might be equivalent to taking 20-30mcg combined oral contraceptive pill. Therefore, prescribing therapeutic doses of norethisterone for women with significant risk factors for venous thromboembolism ( VTE) may therefore be inappropriate. Who shouldn’t be given norethisterone? Obese Personal h/o VTE Strong FH of VTE Immobile/wheelchair bound Carriers of thrombophilia Any other condition predisposing to VTE If my patient can’t take norethisterone, what are the alternatives? The metabolism to ethinyl oestradiol occurs with doses of norethisterone 5mg and over and therefore, the concern does not apply to or other progestogens or contraceptive pills containing norethisterone. Mansour suggested Medroxyprogesterone ( MPA ) 10mg three times a day to reduce heavy menstrual bleeding. Dr Sarah Grey (personal communication) recommends 20mg medroxyprogesterone to be taken daily, starting 3 days before the expected onset of menses. However, (MPA) is not licensed for this use and the prescriber should follow the rules of off label prescribing. References Safer prescribing of therapeutic norethisterone for women at risk of venous thromboembolism. Mansour JFPRHC July 2012 Formation of ethinyl oestradiol in women during treatment with norethisterone acetate. -

Vaginal Administration of Contraceptives

Scientia Pharmaceutica Review Vaginal Administration of Contraceptives Esmat Jalalvandi 1,*, Hafez Jafari 2 , Christiani A. Amorim 3 , Denise Freitas Siqueira Petri 4 , Lei Nie 5,* and Amin Shavandi 2,* 1 School of Engineering and Physical Sciences, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh EH14 4AS, UK 2 BioMatter Unit, École Polytechnique de Bruxelles, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Avenue F.D. Roosevelt, 50-CP 165/61, 1050 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] 3 Pôle de Recherche en Gynécologie, Institut de Recherche Expérimentale et Clinique, Université Catholique de Louvain, 1200 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] 4 Fundamental Chemistry Department, Institute of Chemistry, University of São Paulo, Av. Prof. Lineu Prestes 748, São Paulo 05508-000, Brazil; [email protected] 5 College of Life Sciences, Xinyang Normal University, Xinyang 464000, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (E.J.); [email protected] (L.N.); [email protected] (A.S.); Tel.: +32-2-650-3681 (A.S.) Abstract: While contraceptive drugs have enabled many people to decide when they want to have a baby, more than 100 million unintended pregnancies each year in the world may indicate the contraceptive requirement of many people has not been well addressed yet. The vagina is a well- established and practical route for the delivery of various pharmacological molecules, including contraceptives. This review aims to present an overview of different contraceptive methods focusing on the vaginal route of delivery for contraceptives, including current developments, discussing the potentials and limitations of the modern methods, designs, and how well each method performs for delivering the contraceptives and preventing pregnancy. -

Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2013 Adapted from the World Health Organization Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2Nd Edition

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Early Release / Vol. 62 June 14, 2013 U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2013 Adapted from the World Health Organization Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2nd Edition Continuing Education Examination available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/cme/conted.html. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Early Release CONTENTS CONTENTS (Continued) Introduction ............................................................................................................1 Appendix A: Summary Chart of U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Methods ....................................................................................................................2 Contraceptive Use, 2010 .................................................................................. 47 How To Use This Document ...............................................................................3 Appendix B: When To Start Using Specific Contraceptive Summary of Changes from WHO SPR ............................................................4 Methods .............................................................................................................. 55 Contraceptive Method Choice .........................................................................4 Appendix C: Examinations and Tests Needed Before Initiation of Maintaining Updated Guidance ......................................................................4 Contraceptive Methods -

Biomedical Technology and Devices Handbook

1140_bookreps.fm Page 1 Tuesday, July 15, 2003 9:47 AM 29 Pharmaceutical Technical Background on Delivery Methods CONTENTS 29.1 Introduction 29.2 Central Nervous System: Drug Delivery Challenges to Delivery: The Blood Brain Barrier • Indirect Routes of Administration • Direct Routes of Administration 29.3 Cardiovascular System: Drug Delivery Chronotherapeutics • Grafts/Stents 29.4 Orthopedic: Drug Delivery Metabolic Bone Diseases 29.5 Muscular System: Drug Delivery 29.6 Sensory: Drug Delivery Ultrasound • Iontophoresis/Electroporation 29.7 Digestive System: Drug Delivery GI Stents • Colonic Drug Delivery 29.8 Pulmonary: Drug Delivery Indirect Routes of Administration • Direct Routes of Robert S. Litman Administration Nova Southeastern University 29.9 Ear, Nose, and Throat: Drug Delivery Maria de la Cova The Ear • The Nose • The Throat 29.10 Lymphatic System: Drug Delivery Icel Gonzalez 29.11 Reproductive System: Drug Delivery University of Memphis Contraceptive Implants • Contraceptive Patch • Male Contraceptive Eduardo Lopez References 29.1 Introduction In the evolution of drug development and manufacturing, drug delivery systems have risen to the forefront in the latest of pharmaceutical advances. There are many new pharmacological entities discov- ered each year, each with its own unique mechanism of action. Each drug will demonstrate its own pharmacokinetic profile. This profile may be changed by altering the drug delivery system to the target site. In order for a drug to demonstrate its pharmacological activity it must be absorbed, transported to the appropriate tissue or target organ, penetrate to the responding subcellular structure, and elicit a response or change an ongoing process. The drug may be simultaneously or sequentially distributed to a variety of tissues, bound or stored, further metabolized to active or inactive products, and eventually © 2004 by CRC Press LLC 1140_bookreps.fm Page 2 Tuesday, July 15, 2003 9:47 AM 29-2 Biomedical Technology and Devices Handbook excreted from the body. -

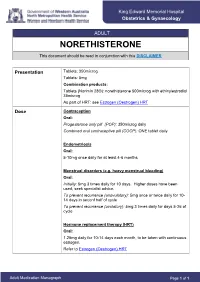

NORETHISTERONE This Document Should Be Read in Conjunction with This DISCLAIMER

King Edward Memorial Hospital Obstetrics & Gynaecology ADULT NORETHISTERONE This document should be read in conjunction with this DISCLAIMER Presentation Tablets: 350microg Tablets: 5mg Combination products: Tablets (Norimin 28®): norethisterone 500microg with ethinylestradiol 35microg As part of HRT: see Estrogen (Oestrogen) HRT Dose Contraception Oral: Progesterone only pill (POP): 350microg daily Combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP): ONE tablet daily Endometriosis Oral: 5-10mg once daily for at least 4-6 months Menstrual disorders (e.g. heavy menstrual bleeding) Oral: Initially: 5mg 3 times daily for 10 days. Higher doses have been used; seek specialist advice. To prevent recurrence (anovulatory): 5mg once or twice daily for 10- 14 days in seconf half of cycle To prevent recurrence (ovulatory): 5mg 3 times daily for days 5-26 of cycle Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) Oral: 1.25mg daily for 10-14 days each month, to be taken with continuous estrogen. Refer to Estrogen (Oestrogen) HRT Adult Medication Monograph Page 1 of 1 Norethisterone – Adult Administration Oral To be taken at the same time each day (or within 3 hours of the usual dose time). For Contraception: Start 4 weeks after the birth of baby (increased risk of abnormal vaginal bleeding if started earlier) Pregnancy 1st Trimester: Contraindicated 2nd Trimester: Contraindicated 3rd Trimester: Contraindicated Breastfeeding Considered safe to use. Progestogens are the preferred hormonal contraceptives as they do not inhibit lactation. Clinical Guidelines Estrogen (Oestrogen) HRT and Policies Progesterone Only Pill Contraception: Post Partum Gynaecology (Non-Oncological) Australian Medicines Handbook. Norethisterone. In: Australian References Medicines Handbook [Internet]. Adelaide (South Australia): Australian Medicines Handbook; 2017 [cited 2017 Apr 12]. -

VTE Prophylaxis in Gynecologic Surgery

ClinicalProviding Information Evidence-based for 25 Years AHC Media LLC Home Page—www.ahcmedia.com CME for Physicians—www.cmeweb.com EDITOR VTE Prophylaxis in Gynecologic Jeffrey T. Jensen, MD, MPH Leon Speroff Professor and Vice Chair for Research Surgery: Quo Vadis? Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology ABSTRACT & COMMENTARY Oregon Health & Science University InsIde Portland Oligohydram- By Robert L. Coleman, MD ASSOCIATE EDITORS nios: A reason Sarah L. Berga, MD Professor and Chair to deliver? Professor, University of Texas; M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston Department of Obstetrics and page 59 Gynecology Vice President for Women’s Dr. Coleman reports no financial relationships relevant to this field of study. Health Services Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, NC Which is Synopsis: Venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis better: Open, Robert L. Coleman, MD interventions in gynecologic surgery are meritorious, supported Professor, University of laparoscopic, by Level 1 evidence and the subject of multiple guidelines, including Texas; M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston or robotic? those published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. However, new evidence suggests nearly Alison Edelman, MD, MPH page 60 Associate Professor, one-third of women undergoing hysterectomy in this country Assistant Director of the still receive no VTE prophylaxis, placing thousands of women at Family Planning Fellowship Special Department of Obstetrics & unnecessary risk for preventable morbidity. Gynecology, Oregon Health feature: & Science University, Portland Do we have a Source: Wright JD, et al. Quality of perioperative venous thromboembolism John C. Hobbins, MD problem? prophylaxis in gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:978-986. Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Obesity and University of Colorado Health contraception he objective of this study was to estimate the use of vte pro- Sciences Center, Denver page 61 Tphylaxis in women undergoing major gynecologic surgery and to Frank W.