Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Policia Militar Do Estado Do Rio De Janeiro Edital

POLICIA MILITAR DO ESTADO DO RIO DE JANEIRO EDITAL CENTRO DE RECRUTAMENTO E SELEÇÃO DE PRAÇAS – CRSP CONCURSO AO CURSO DE FORMAÇÃO DE SOLDADOS DA POLICIA MILITAR DO ESTADO DO RIO DE JANEIRO – CFSd/2014 RETIFICAÇÃO DO RESULTADO FINAL DA ETAPA MÉDICA O Comandante Geral da Policia Militar do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, no uso de suas atribuições legais, torna público o resultado final da Etapa médica do concurso CFSd /2014. Serão disponibilizados 02 (dois) dias para interposição de recursos, 25 e 26 de junho de 2018, referentes a retificação do resultado final da etapa dos exames médicos do CFSd/2014, no endereço eletrônico da Exatus www.exatuspr.com.br. INSC NOME RESULTADO 1523427 ABEL GOMES DA COSTA JUNIOR APTO 1566820 ABEL JUSTINO SILVEIRA JUNIOR APTO 1569107 ABILIO JEFFERSON FERREIRA DA SILVA APTO 1586022 ABNER DE SOUZA AMORIM APTO 1530070 ABNER DE SOUZA VELLOSO APTO 1655811 ABNER FERREIRA PENNA JUNIOR APTO 1664179 ABNER FREITAS MAGALHAES APTO 1684521 ABRAHAO LEVI ALVES DA SILVA APTO 1676442 ADAILTON FRANCISCO DE LIMA RAMOS APTO 1574997 ADALBERTO DA CONCEIçãO REGO APTO 1646894 ADALBERTO SILVA DE SOUZA INAPTO 1652594 ADALBERTO SOUZA DE RESENDE APTO 1571702 ADALTON GONçALVES ROSA APTO 1568584 ADAM DE OLIVIERA DE PAULA APTO 1575236 ADAUTO LOBO DE SOUZA JUNIOR APTO 1517437 ADELIANE RODRIGUES DE OLIVEIRA APTO 1557566 ADEMAR LIMA VIEIRA INAPTO 1543490 ADEMILSON ALVES DA SILVA JUNIOR APTO 1654936 ADEMILSON FRANCISCO DA SILVA APTO 1550612 ADEMIR FERRAZ DA SILVA APTO 1631201 ADENILSON RODRIGUES DE SOUZA APTO 1512253 ADIELSON SILVA DE OLIVEIRA APTO -

— Olympic Games — Lachkovics 10.44; 9

■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ Volume 46, No. 12 NEWSLETTERNEWSLETTER ■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■track October 31, 2000 II(0.3)–1. Boldon 10.11; 2. Collins 10.19; 3. Surin 10.20; 4. Gardener 10.27; 5. Williams 10.30; 6. Mayola 10.35; 7. Balcerzak 10.38; 8. — Olympic Games — Lachkovics 10.44; 9. Batangdon 10.52. III(0.8)–1. Thompson 10.04; 2. Shirvington 10.13; 3. Zakari 10.22; 4. Frater 10.23; 5. de SYDNEY, Australia, September 22–25, 10.42; 4. Tommy Kafri (Isr) 10.43; 5. Christian Lima 10.28; 6. Patros 10.33; 7. Rurak 10.38; 8. 27–October 1. Nsiah (Gha) 10.44; 6. Francesco Scuderi (Ita) Bailey 11.36. Attendance: 9/22—97,432/102,485; 9/23— 10.50; 7. Idrissa Sanou (BkF) 10.60; 8. Yous- IV(0.8)–1. Chambers 10.12; 2. Drummond 92,655/104,228; 9/24—85,806/101,772; 9/ souf Simpara (Mli) 10.82;… dnf—Ronald Pro- 10.15; 3. Ito 10.25; 4. Buckland 10.26; 5. Bous- 25—92,154/112,524; 9/27—96,127/102,844; messe (StL). sombo 10.27; 6. Tilli 10.27; 7. Quinn 10.27; 8. 9/28—89,254/106,106; 9/29—94,127/99,428; VI(0.2)–1. Greene 10.31; 2. Collins 10.39; 3. Jarrett 16.40. 9/30—105,448; 10/1—(marathon finish and Joseph Batangdon (Cmr) 10.45; 4. Andrea V(0.2)–1. Campbell 10.21; 2. C. Johnson Closing Ceremonies) 114,714. Colombo (Ita) 10.52; 5. Watson Nyambek (Mal) 10.24; 3. -

Dd343a80576a07645d9f92adc7

RELATÓRIO DESCRITIVO DE GESTÃO Janeiro à junho de 2020. Gestor da Unidade: Diego Pereira Diretor Operacional: Ênylo Vinicius Faria Nome da Unidade: UPA NOVA CIDADE Município: SÃO GONÇALO Contrato de Gestão: 0022016 Página 60 de 60 InSaúde – Instituto Nacional de Pesquisa e Gestão em Saúde Umpa de Nova Cidade Processo nº: 906 Rua Vicente de Lima Cleto, s/n • Nova Cidade • São Gonçalo • RJ • CEP 24455-000 E-mail: [email protected] • F. (21) 2706.2192/3606.6893 • www.insaude.org.br Sumário Apresentação do Relatório ................................................................................................................ 2 Identidade Organizacional ................................................................................................................ 3 O InSaúde ...................................................................................................................................... 3 ORGANOGRAMA INSTITUCIONAL ....................................................................................................... 3 A Unidade Gerenciada .................................................................................................................. 4 PERFIL INSTITUCIONAL ..................................................................................................................... 4 ORGANOGRAMA ........................................................................................................................... 13 Contrato de Gestão ........................................................................................................................ -

X UFRJ INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM on MUSICOLOGY “SIM-UFRJ CELEBRATES ITS 10 YEARS” School of Music / Graduate Studies Program Rio De Janeiro, August 12–16, 2019

X UFRJ INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON MUSICOLOGY “SIM-UFRJ CELEBRATES ITS 10 YEARS” School of Music / Graduate Studies Program Rio de Janeiro, August 12–16, 2019 General Committee Maria José Chevitarese (UFRJ), Chair Pauxy Gentil-Nunes (UFRJ) Maria Alice Volpe (UFRJ) Marcelo Jardim (UFRJ) Ronal Silveira (UFRJ) Beth Villela (UFRJ) Mário Alexandre Dantas Barbosa (UFRJ) Ivette Céspedes Gomes (UFRJ) Rafaela Theodoro da Fonseca (UFRJ) Program Committee Maria Alice Volpe (UFRJ), Chair Andrea Adour da Câmara (UFRJ), Submission Coordinator Antonio Augusto, Coordinator of the Research Line History and Documentation of Brazilian and Ibero-American Music (UFRJ) Frederico Barros, Coordinator of the Research Line Ethnography of Musical Practices (UFRJ) Sérgio Álvares, Coordinator of the Research Line Music, Education and Diversity (UFRJ) Carlos Almada, Coordinator of the Research Line Poetics of Music Creation (UFRJ) Pedro Bittencourt, Coordinator of the Research Line Interpretive Practices and their Reflective Processes (UFRJ) Edilson Vicente de Lima (Federal University of Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais, Brazil) Manuel Pedro Ferreira (NOVA - New University of Lisbon, Portugal) II Extension course “Pedagogy of the History of Brazilian Music for Basic Education” Maria Alice Volpe, Coordinator Mário Alexandre Dantas Barbosa (UFRJ e CPII), Pedagogical Coordinator Pedagogical Nucleus Mário Alexandre Dantas Barbosa (UFRJ e CPII) Anna Cristina Cardozo Fonseca (CPII) João Miguel Bellard Freire (UFRJ) Aline Santos da Paz de Souza (UFRJ and Prefeitura Municipal do Rio de Janeiro) Nucleus of Academic Integration between Undergraduate and Graduate Studies Tiago dos Santos de Souza (UFRJ) Silviane Paiva de Noronha (UFRJ) CALL FOR PAPERS The School of Music and the Graduate Studies Program announce the X International Symposium on Musicology of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, to be held from August 12 to 16, 2019, and welcome the submission of proposals. -

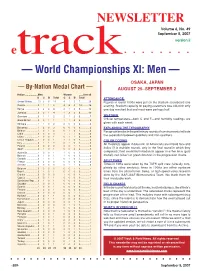

NEWSLETTER Volume 6, No

NEWSLETTER Volume 6, No. 49 September 5, 2007 version ii etrack — World Championships XI: Men — OSAKA, JAPAN — By-Nation Medal Chart — AUGUST 25–SEPTEMBER 2 Nation ..................Men Women ......Overall G S B Total G S B Total ATTENDANCE United States .......10 3 6 19 4 1 2 7 ............26 Figures in round 1000s were put on the stadium scoreboard one Russia ..................0 1 1 2 4 8 2 14 ..........16 evening. Stadium capacity for paying customers was c36,000; only Kenya ..................3 2 3 8 2 1 2 5 ............13 one day reached that and most were perhaps half. Jamaica ...............0 3 1 4 1 3 2 6 ............10 Germany ..............0 1 1 2 2 1 2 5 ..............7 WEATHER Great Britain .........0 0 1 1 1 1 2 4 ..............5 Official temperature—both C and F—and humidity readings are Ethiopia ................1 1 0 2 2 0 0 2 ..............4 given with each event. Bahamas ..............1 2 0 3 0 0 0 0 ..............3 EXPLAINING THE TYPOGRAPHY Belarus ................1 0 1 2 0 1 0 1 ..............3 Paragraph breaks in the preliminary rounds of running events indicate Cuba ....................0 0 0 0 1 1 1 3 ..............3 the separation between qualifiers and non-qualifiers. China ...................1 0 0 1 0 1 1 2 ..............3 Czech Republic ....1 0 0 1 1 1 0 2 ..............3 COLOR CODING Italy ......................0 1 1 2 0 1 0 1 ..............3 All medalists appear in blue ink; all Americans are in bold face and Poland .................0 0 2 2 0 0 1 1 ..............3 Spain ...................0 1 0 1 0 0 2 2 ..............3 italics (if in multiple rounds, only in the final round in which they Australia ...............1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 ..............2 competed); field-event/multi medalists appear in either blue (gold Bahrain ................0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 ..............2 medal), red (silver) or green (bronze) in the progression charts. -

Varas De Falências

Disponibilização: quarta-feira, 27 de julho de 2016 Diário da Justiça Eletrônico - Caderno Editais e Leilões São Paulo, Ano IX - Edição 2166 7 Varas de Falências 2ª Vara de Falência e Recuperações Judiciais EDITAL - RELAÇÃO DE CREDORES, COM PRAZO DE 10 (DEZ) DIAS, expedido nos autos da ação de Falência de Empresários, Sociedades Empresáriais, Microempresas e Empresas de Pequeno Porte - Autofalência de Banco Cruzeiro do Sul S/A e outros, PROCESSO Nº 1071548-40.2015.8.26.0100.EDITAL - RELAÇÃO DE CREDORES, COM PRAZO DE 10 (DEZ) DIAS, (artigo 7°, § 2° da Lei n° 11.101/2005) com prazo de 10 dias para impugnação contra a Relação de Credores (artigo 8º da Lei n° 11.101/2005), expedido nos autos da Falência do BANCO CRUZEIRO DO SUL S/A E OUTROS. n° 1071548- 40.2015.8.26.0100. O Doutor Paulo Furtado de Oliveira Filho, MM. Juiz de Direito da 2ª Vara de Falências e Recuperações Judiciais do Foro Central da Comarca da Capital do Estado de São Paulo, na forma da Lei, etc. FAZ SABER, a todos quantos o presente edital virem ou dele conhecimento tiverem e interessar possa, que por parte da LASPRO CONSULTORES LTDA., representada pelo Dr. Oreste Nestor de Souza Laspro, OAB/SP n° 98.628, nomeada Administradora Judicial nos autos do Pedido de Autofalência requerida por banco cruzeiro do sul s/a; cruzeiro do sul holding financeira s/a; cruzeiro do sul s/a corretora de valores e mercadorias; cruzeiro do sul s/a distribuidora de títulos e valorEs mobiliários; cruzeiro do sul s/a companhia securitizadora de créditos financeiros (processo n° 1071548-40.2015.8.26.0100), -

As Primeiras Manifestações Da Música Popular Urbana No Brasil

A MODINHA E O LUNDU NO BRASIL As primeiras manifestações da música popular urbana no Brasil EDILSON V ICENTE DE LIMA om crescimento populacional que vinha se acentuando Uma outra forma de entretenimento que vinha desde o início do século XVIII e a formação de centros sendo praticada no Brasil desde meados do século urbanos (tais como Salvador, Ouro Preto, Rio XVIII era a música patrocinada por proprietários de Janeiro, dentre outros), a demanda por um certo de posses, que mantinham orquestra formada por Ctipo de entretenimento por parte de uma classe média escravos negros especialmente treinados para emergente era condição imperiosa para a manutenção executarem os mais diversos instrumentos (violinos, de um modelo de cultura que a metrópole, no caso viola, teclado, charamelas, dentre outros). Portugal, vinha impondo à colônia. As músicas que interpretavam eram os sucessos Antes dos concertos públicos, que só viriam europeus que nos chegavam às mãos (Kiefer, 1982). a acontecer no início do século XIX em Portugal (Nery, Porém, tais eventos ocorriam em recintos fechados 1991) e mais tardiamente no Brasil, o lazer era e para convidados especiais. praticado de diversas maneiras, tanto na Corte quanto na colônia: as óperas, encenadas desde o século XVIII; as festas profanas, tais como aniversários de cidades, Página ao lado: Domingos Caldas Barbosa. membros da família real ou alguma figura importante 1ª edição da obra Viola de Lereno. Lisboa. Na Officina Nunesiana. pertencente à classe dominante; as festas religiosas, Anno 1798. que também tinham funções sociais. FUNDAÇÃO BIBLIOTECA NACIONAL – DIVISÃO DE OBRAS RARAS 46 Os saraus praticados pelas elites, entre os séculos XVIII e XIX, também foram formas de lazer, e, por conseguinte, de divulgação da música cultivada pela classe média em sua vida cotidiana. -

A Modinha E O Lundu: Dois Clássicos Nos Trópicos

EDILSON VICENTE DE LIMA A modinha e o lundu: dois clássicos nos trópicos Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Música, Área de Concentração Musicologia, Linha de Pesquisa: História, Estilo e Recepção, da Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo, como exigência parcial para a obtenção do Título de Doutor em Musicologia, sob a orientação do Prof. Dr. Régis Duprat. São Paulo 2010 1 EDILSON VICENTE DE LIMA A modinha e o lundu: dois clássicos nos trópicos Comissão julgadora __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ São Paulo ____ , de ____________ de 2010 2 Dedico este trabalho: Aos meus pais: Cícero Vicente de Lima e Quitéria Moreira de Lima. A todos os meus queridos familiares e amigos. Ao meu querido amigo de juventude, Antonio José da Silva. Aos meus amigos de universidade: Paulo Augusto Soares, Celso Cintra e Milton Castelli. À Universidade Cruzeiro do Sul que sempre me acolheu e às amizades que lá desenvolvi. Serei eternamente grato à: Todos os meus professores: que ousaram contribuir para minha formação; Regis Duprat: aquele a quem nunca encontrarei palavras suficientes para expressar meu reconhecimento; Rosemeire Moreira: a voz que Rousseau não teve oportunidade de ouvir. 3 RESUMO A tese por nós defendida no texto que se segue tem como objetivo o estudo de dois importantes gêneros musicais, a modinha e o lundu, cujos processos de elaboração iniciam-se a partir da segunda metade do século XVIII no seio da sociedade luso-brasileira. Com o intuito de possibilitar uma reflexão mais abrangente do assunto, muito caro à historiografia musical em língua lusófona, são levados em consideração aqui, aspectos históricos, estilísticos e identitários. -

Grid Export Data

Full Name Country ABBASI, Asli Iran ABDULLAH, Azrina Malaysia ABED, Sheila Paraguay ACUÑA, Guillermo Chile ADDIS, Daniela Italy AFRIANSYAH, Arie Indonesia AGAFONOV, Vassily Russia AGBEMELO-TSOMAFO, Joel Togo AGOSTINHO, Rodrigo Brazil AGOSTINI, Andreia Brazil AGUILAR ROJAS, Grethel Costa Rica AHMAD, Nadia United States of America AHMED, Murad United Arab Emirates AHUJA, Naysa India AJAI, Olawale Nigeria AKAMINE, Midori United States of America AKHTAR-KHAVARI, Afshin Australia AKOLO-TAUTAKITAKI, Jolene Fiji AKPOVI, Rémy Benin AKRAM, Imran Pakistan AKUS, Tamalis Papua New Guinea ALADOUA, Saadou Niger ALANIS ORTEGA, Gustavo Mexico ALBAN, Maria Ecuador ALDANA, Martha Peru ALGHAMDI, Bandar Saudi Arabia ALHOSANI, Kholoud United Arab Emirates ALI, El Tayeb Murkaz Sudan ALJAZY, Ibrahim Jordan ALLEN, John Rodney Switzerland ALLY-SAID, Matano Kenya AL-MOUMIN, Mishkat United States of America AL-TURK, Esra`a Jordan ALZAYED, Yousef Kuwait AMADI, John New Zealand AMADOR, Teresa Portugal AMATO, Alessandro Italy AMBROSE, David India AMERASINGHE, Niranjali United States of America AMIRANTE, Domenico Italy AMOS, William Canada ANDALUZ WESTREICHER, Carlos Alberto Peru ANDREEN, William United States of America ANDRUSEVYCH, Andriy Ukraine ANGSTADT, J. Michael United States of America ANSARI, Abdul Malaysia ANTOLINI, Denise United States of America ANTON, Donald Australia ARANDA ORTEGA, Jorge Chile ARAUJO, Francisco Brazil ARAÚJO, Juliano Brazil ARIAS, Verónica Ecuador ARICKO, Huguette Côte d'Ivoire ARRÉLLAGA, María United States of America ARRIETA, Lilliana -

Psicotecnico

2ª LISTA RESULTADO AVALIAÇÃO PSICOLÓGICA PMERJ - CFSD O CANDIDATO DEVERÁ APRESENTAR RECURSO ATRAVÉS DO SITE WWW.EXATUSPR.COM.BR - ABA RECURSOS NOS DIAS ÚTEIS DE 04, 05 E 06/02/2015 INSC NOME SEXO COTISTA CLASS SITUAÇÃO 1666654 RAPHAEL MARINS DA SILVA ma SIM 1 APTO 1523002WESLLEY ADRIANO DE OLIVEIRA AGUIAR ma SIM 2 APTO 1608557 RAPHAEL DO NASCIMENTO REIS ma SIM 3 APTO 1675767 JOCHUAM MONTEIRO DA SILVA ma SIM 4 APTO 1692044 PEDRO PAULO DOS SANTOS MACHADO ma SIM 5 APTO 1666549 JULIAN EUZéBIO CHAGAS DA COSTA ma SIM 6 APTO 1565337LEONARDO DOS SANTOS BARBOSA ma SIM 7 APTO 1691982 DANIEL OLIVEIRA SILVA ma SIM 8 APTO 1633712 HEIDER CABRAL DA SILVA ma SIM 9 APTO 1530426 MARCOS LIMA SILVA ma SIM 10 APTO 1666458VICTOR HUGO PEREIRA GALANTE ma SIM 11 APTO 1702293 EDUARDO OLIVEIRA VENTURA ma SIM 12 APTO 1612592 FELIPE VICENTE DA SILVA ma SIM 13 APTO 1513830 AILTON DA COSTA NASCIMENTO ma SIM 14 APTO 1670331 YURI PRUSS DE QUEIROZ ma SIM 15 APTO 1538080FELLIPE RAFAEL SANTOS DE SOUZA ma SIM 16 APTO 1685888 JULIO DA SILVA APOLINARIO ma SIM 17 APTO 1547581WALTER CéSAR DA SILVA CARVALHO ma SIM 18 APTO 1689459 MATHIAS GONçALVES GUIMARâES ma SIM 19 APTO 1558941LUTERCIO GALIZA DE SOUZA FILHO ma SIM 20 APTO 1553494 PAULO MARCIO FONSECA ma SIM 21 APTO 1654608JULIO CESAR MONTENEGRO DA SURREIçãO ma SIM 22 APTO 1518332 FELIPE ALCANTARA DA SILVA ma SIM 23 APTO 1518076 BRUNO MATIAS SILVA ma SIM 24 APTO 1513983 MAXUELL COSTA PESSANHA ma SIM 25 APTO 1528199BRUNO NOGUEIRA DA SILVA PEREIRA ma SIM 26 APTO 1600856 ALEX CORRÊA GERMANO ma SIM 27 APTO 1572347 JOSIVALDO LUCIANO -

Grid Export Data

Full Name Country ABBASI, Asli Iran ABDULLAH, Azrina Malaysia ABED, Sheila Paraguay ABU AL-ASSAM, AL-Sharifeh Nawzat Jordan ACUÑA, Guillermo Chile ADDIS, Daniela Italy AFRIANSYAH, Arie Indonesia AGAFONOV, Vassily Russia AGBEMELO-TSOMAFO, Joel Togo AGOSTINHO, Rodrigo Brazil AGOSTINI, Andreia Brazil AGUILAR, Grethel Costa Rica AHMAD, Nadia United States of America AHMED, Murad United Arab Emirates AHUJA, Naysa United States of America AJAI, Olawale Nigeria AKAMINE, Midori United States of America AKHTARKHAVARI, Afshin Australia AKOLO-TAUTAKITAKI, Jolene Fiji AKPOVI, Rémy Benin AKRAM, Imran Pakistan AKUS, Tamalis Papua New Guinea ALADOUA, Saadou Niger ALANIS ORTEGA, Gustavo Mexico ALBAN, Maria Ecuador ALDANA, Martha Peru ALGHAMDI, Bandar Saudi Arabia ALI, El Tayeb Murkaz Sudan ALJAZY, Ibrahim Jordan ALLEN, John Rodney Switzerland ALLY-SAID, Matano Kenya AL-MOUMIN, Mishkat United States of America AL-TURK, Esra`a Jordan ALZAYED, Yousef Kuwait AMADI, John New Zealand AMADOR, Teresa Portugal AMATO, Alessandro Italy AMERASINGHE, Niranjali United States of America AMIRANTE, Domenico Italy AMOS, William Canada ANDALUZ WESTREICHER, Carlos Alberto Peru ANDREEN, William United States of America ANDRUSEVYCH, Andriy Ukraine ANSARI, Abdul Malaysia ANTOLINI, Denise United States of America ANTON, Donald Australia ARANDA ORTEGA, Jorge Chile ARAUJO, Francisco Brazil ARAÚJO, Juliano Brazil ARIAS, Verónica Ecuador ARICKO, Huguette Côte d'Ivoire ARRÉLLAGA, María United States of America ARRIETA, Lilliana Costa Rica ARTIAGA, Yvonne Philippines ARYAL, Ravi Nepal -

Parliamentarians at Risk Around the World

Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission Briefing Co-hosted by the House Democracy Partnership Parliamentarians at Risk Around the World Panel I Delsa Solórzano is a lawyer and member of the National Assembly of Venezuela for the period 2016 to 2021. From 2016 to 2018 she was President of the Assembly's Permanent Commission of Internal Political Affairs. Ms. Solorzano was Vice President of Venezuela's social-democratic party "Un Nuevo Tiempo" from which she separated in December 2018 to create her own political movement. She served as a member of the Latin American Parliament, Venezuela chapter, from 2011 to 2016. In January 2019, Ms. Solorzano was elected Vice President of the Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians of the Inter- Parliamentary Union which aims to defend the rights of parliamentarians across the world who are at risk. Hisyar Ozsoy is a Kurdish member of parliament in Turkey with the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP). Mr Ozsoy is the vice-president of the HDP responsible for foreign affairs and a member of the parliamentary Foreign Affairs Commission. He simultaneously serves as a member of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), the Inter- Parliamentary Union (IPU), and the NATO Parliamentary Assembly. He has longstanding ties with the United States and holds M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in political anthropology from the University of Texas at Austin. He has taught courses in political sociology, cultural anthropology, and Middle Eastern cultures and politics at the University of Michigan-Flint. Bios, Parliamentarians at Risk, Page 1 of 2 Vicente de Lima is the brother of Senator Leila de Lima of the Philippines, As Chairperson of the Commission on Human Rights of the Philippines from 2008 to 2010, Senator de Lima led a series of investigations into alleged extrajudicial killings linked to the so-called Davao Death Squad in Davao City, where Rodrigo Duterte had long been mayor.