B017 Braille Music and Unified English Braille

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unified English Braille Webinar Presentation

Unified English Braille: A Place to Start Webinar • UEB Ain't Hard to Do by Mark Brady a NYC Teacher of the Visually Impaired • The lyrics and sound file can be found on the Paths to Literacy website • http://www.pathstoliteracy.org/resources/farewell-song-9-ebae- contractions Unified English Braille A Place to Start April 2016 Donna Mayberry, M.Ed., NCUEB LAUREL REGIONAL PROGRAM, Lynchburg, VA [email protected] Webinar Content: • Overview of UEB • Unified English Braille Reference Sheets • Unified English Braille Student Progress Checklists • Converting Bookshare files into UEB • Teacher Relicensure: Option 8 • NCUEB • Questions Overview of UEB The Rules of Unified English Braille Second Edition 2013 Available as a PDF or BRF http://www.iceb.org/ueb.html Your new best Friend!!! What are teacher’s using to learn UEB? •Hadley School for the Blind •VDBVI Saturday Seminars •Update to UEB Self Directed Course- Available in Word, PDF, BRF, DXB http://www.cnib.ca/en/living/braille/Pages/Transcribers-UEB-Course.aspx •The new textbook that is being used in the VI Consortium is: Ashcroft's Programmed Instruction: Unified English Braille by M. Cay Holbrook 2014 Braille Not Used in Unified English Braille Contractions o'c o'clock (shortform) 4 dd (groupsign between letters) 6 to (wordsign unspaced from following word) 96 into (wordsign unspaced from following word) 0 by (wordsign unspaced from following word) # ble (groupsign following other letters) - com (groupsign at beginning of word) ,n ation (groupsign following other letters) ,y ally (groupsign following other letters) Braille Not Used in Unified English Braille- 2 Punctuation 7 opening and closing parentheses (round brackets) 7' closing square bracket 0' closing single quotation mark (inverted commas) ''' ellipsis -- dash (short dash) ---- double dash (long dash) ,7 opening square bracket Braille Not Used in Unified English Braille- 3 Composition signs (indicators) 1 non-Latin (non-Roman) letter indicator @ accent sign (nonspecific) @ print symbol indicator . -

Nemeth Code Uses Some Parts of Textbook Format but Has Some Idiosyncrasies of Its Own

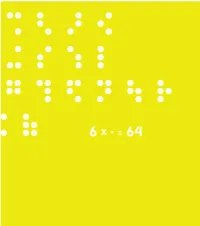

This book is a compilation of research, in “Understanding and Tracing the Problem faced by the Visually Impaired while doing Mathematics” as a Diploma project by Aarti Vashisht at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. 6 DOTS 64 COMBINATIONS A Braille character is formed out of a combination of six dots. Including the blank space, sixty four combinations are possible using one or more of these six dots. CONTENTS Introduction 2 About Braille 32 Mathematics for the Visually Impaired 120 Learning Mathematics 168 C o n c l u s i o n 172 P e o p l e a n d P l a c e s 190 Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION This project tries to understand the nature of the problems that are faced by the visually impaired within the realm of mathematics. It is a summary of my understanding of the problems in this field that may be taken forward to guide those individuals who are concerned about this subject. My education in design has encouraged interest in this field. As a designer I have learnt to be aware of my community and its needs, to detect areas where design can reach out and assist, if not resolve, a problem. Thus began, my search, where I sought to grasp a fuller understanding of the situation by looking at the various mediums that would help better communication. During the project I realized that more often than not work happened in individual pockets which in turn would lead to regionalization of many ideas and opportunities. Data collection got repetitive, which would delay or sometimes even hinder the process. -

World Braille Usage, Third Edition

World Braille Usage Third Edition Perkins International Council on English Braille National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped Library of Congress UNESCO Washington, D.C. 2013 Published by Perkins 175 North Beacon Street Watertown, MA, 02472, USA International Council on English Braille c/o CNIB 1929 Bayview Avenue Toronto, Ontario Canada M4G 3E8 and National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., USA Copyright © 1954, 1990 by UNESCO. Used by permission 2013. Printed in the United States by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data World braille usage. — Third edition. page cm Includes index. ISBN 978-0-8444-9564-4 1. Braille. 2. Blind—Printing and writing systems. I. Perkins School for the Blind. II. International Council on English Braille. III. Library of Congress. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. HV1669.W67 2013 411--dc23 2013013833 Contents Foreword to the Third Edition .................................................................................................. viii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... x The International Phonetic Alphabet .......................................................................................... xi References ............................................................................................................................ -

DBT and Japanese Braille

AUSTRALIAN BRAILLE AUTHORITY A subcommittee of the Round Table on Information Access for People with Print Disabilities Inc. www.brailleaustralia.org email: [email protected] Japanese braille and UEB Introduction Japanese is widely studied in Australian schools and this document has been written to assist those who are asked to transcribe Japanese into braille in that context. The Japanese braille code has many rules and these have been simplified for the education sector. Japanese braille has a separate code to that of languages based on the Roman alphabet and code switching may be required to distinguish between Japanese and UEB or text in a Roman script. Transcription for higher education or for a native speaker requires a greater knowledge of the rules surrounding the Japanese braille code than that given in this document. Ideally access to both a fluent Japanese reader and someone who understands all the rules for Japanese braille is required. The website for the Braille Authority of Japan is: http://www.braille.jp/en/. I would like to acknowledge the invaluable advice and input of Yuko Kamada from Braille & Large Print Services, NSW Department of Education whilst preparing this document. Kathy Riessen, Editor May 2019 Japanese print Japanese print uses three types of writing. 1. Kana. There are two sets of Kana. Hiragana and Katana, each character representing a syllable or vowel. Generally Hiragana are used for Japanese words and Katakana for words borrowed from other languages. 2. Kanji. Chinese characters—non-phonetic 3. Rōmaji. The Roman alphabet 1 ABA Japanese and UEB May 2019 Japanese braille does not distinguish between Hiragana, Katakana or Kanji. -

Seedlings' 2020 Annual Report

2020 Annual Report Highlights & Financial Statement Page 3 Seedlings’ Free Programs Page 4 Donor Listing Page 6 Memorial Donations Page 14 Group & Special Donations Page 17 Special Events Page 20 Celebrating 36 Years of Bringing Braille Books to Children Around the World! From Our Director Like so many others, we at Seedlings found 2020 very challenging. The global pandemic drastically changed how we FOUNDED IN 1984 live and work, and many were faced with health concerns and the illness or loss of loved ones. Seedlings’ office was closed for almost two 2020 Board of months until our Shelter in Place order was lifted and we were allowed to slowly start Directors bringing back staff. That caused an 11 percent reduction in our book production in 2020. (Board Members serve 3-year terms as unpaid volunteers.) On the plus side, the experience taught or reminded us of three important things: Arthur Cole, CPA Terry Crouson, Consultant Children with vision loss need more books. When schools and libraries closed, we felt a tremendous responsibility to get more books into our Ann Devereux, President, kids' hands and homes. Parent of a Blind Child Our donors are amazing. They clearly value braille literacy and support Ben Gehle, Treasurer, Banker it even during tough economic times. Despite the pandemic, donations Patty Graff, Secretary, HR remained strong in 2020, for which we are tremendously grateful. Administrator Our volunteers are so valuable. We did Jim Jolly, Attorney, City not want to risk their health by asking Our Mission Council Member them to come in, and we truly missed Seedlings is a nonprofit, Katelyn Kelel, Consultant, them. -

Braille Connect the Dots

Braille Connect the Dots B0050814 2 Contents 4 What is braille? 5 How braille began 6 The alphabet 8 Numbers 9 Capitals, punctuation and spacing 11 Common phrases 12 Contracted braille 13 Getting more technical 15 Writing braille 19 Using braille 23 Braille opens doors 24 W here do I go to learn more about braille? 25 Ho w can I get documents made into braille? 27 Important contacts and links 28 Summar y of alphabet and numbers 3 What is braille? Braille is the reading and writing system used by blind people all over the world. It is bumps or dots that blind people read with their fingers. As well as braille books, there are braille menus, recipes, board games and playing cards. You can even find braille on some packaging, ATM machines, lift buttons and other signs. In this booklet, we’re going to teach you some braille basics. There are activities and some great links so you can get more information. 4 How braille began Braille was invented by a French boy in 1824. His name was Louis Braille. Here’s some of his story. Louis Braille was born in 1809. He became blind due to an accident at the age of three, and later attended the first school for the blind in Paris from 1819. He was taught to read raised, enlarged print but found it very slow. Also, no one had yet found a way to enable blind people to write. Louis began to look for better ways of reading and writing for blind people. -

IPA Braille: an Updated Tactile Representation of the International Phonetic Alphabet

IPA Braille: An Updated Tactile Representation of the International Phonetic Alphabet Print Edition Overview, Tables, and Sample Texts Edited by Robert Englebretson, Ph.D. Produced by CNIB For the International Council on English Braille 2008 List of ICEB Member Countries As Of April, 2008 Australia Canada New Zealand Nigeria South Africa United Kingdom United States ii Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS BY ROBERT ENGLEBRETSON.............................................. V FOREWORD by Fredric K. Schroeder .................................................................. VII ACCLAIM FOR IPA BRAILLE BY MARTHA PAMPERIN.............................................IX 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1 2. THE SYMBOLS OF THE IPA ............................................................................. 5 2.1. CONSONANTS (PULMONIC) .................................................................. 6 2.2. CONSONANTS (NON-PULMONIC) ....................................................... 11 2.3. OTHER SYMBOLS ................................................................................ 13 2.4. VOWELS ............................................................................................. 15 2.5. DIACRITICS ....................................................................................... 17 2.6. SUPRASEGMENTALS ........................................................................... 23 2.7. TONES & WORD ACCENTS.................................................................. -

Hardware-Based Text-To-Braille Translation

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Hardware -Based Text -to -Braille Translation Xuan Zhang This thesis is presented for the Degree of Master of Engineering of Curtin University of Technology July 2007 Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgment has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature: Date: Abstract Braille, as a special written method of communication for the blind, has been globally accepted for years. It gives blind people another chance to learn and communicate more efficiently with the rest of the world. It also makes possible the translation of printed languages into a written language which is recognisable for blind people. Recently, Braille is experiencing a decreasing popularity due to the use of alternative technologies, like speech synthesis. However, as a form of literacy, Braille is still playing a significant role in the education of people with visual impairments. With the development of electronic technology, Braille turned out to be well suited to computer-aided production because of its coded forms. Software based text-to-Braille translation has been proved to be a successful solution in Assistive Technology (AT). However, the feasibility and advantages of the algorithm reconfiguration based on hardware implementation have rarely been substantially discussed. A hardware-based translation system with algorithm reconfiguration is able to supply greater throughput than a software-based system. Further, it is also expected as a single component integrated in a multi-functional Braille system on a chip. -

The Braille Code: Past - Present - Future

TThhee EEdduuccaattoorr VOLUME XXI, ISSUE 2 January 2009 THE BRAILLE CODE: PAST - PRESENT - FUTURE A Publication of The International Council for Education of ICEVI People with Visual Impairment PRINCIPAL OFFICERS FOUNDING NON-GOVERNMENTAL PRINCIPAL OFFICERS ORGANISATIONS DEVELOPMENT PRESIDENT SECOND VICE PRESIDENT American Foundation ORGANISATIONS Lawrence F. Campbell Harry Svensson for the Blind Asian Foundation for the Overbrook School for the Blind National Agency for Special Carl R. Augusto Prevention of Blindness 6333 Malvern Avenue Needs Education and Philadelphia, PA 19151-2597 Schools 11 Penn Plaza, Suite 300 Grace Chan, JP USA Box 12161, SE- 102 26 New York, NY 10001 c/o The Hong Kong Society [email protected] Stockholm, SWEDEN USA for the Blind [email protected] [email protected] 248 Nam Cheong Street FIRST VICE PRESIDENT Perkins School for the Blind Shamshuipo, Kowloon Jill Keeffe TREASURER HONG KONG Steven M. Rothstein Centre for Eye Research Australia Nandini Rawal [email protected] 175 North Beacon Street University of Melbourne Blind People’s Association Watertown, MA 02472 CBM Jagdish Patel Chowk Department of Ophthalmology USA Locked Bag 8 Surdas Marg, Vastrapur Allen Foster [email protected] East Melbourne 8002 Ahmedabad 380 015 Nibelungenstrasse 124 AUSTRALIA INDIA Royal National Institute 64625 Bensheim [email protected] [email protected] of the Blind GERMANY [email protected] SECRETARY GENERAL Colin Low Mani, M.N.G. 105 Judd Street Norwegian Association of the London WC1H 9NE No.3, Professors’ Colony, Palamalai Road Blind and Partially Sighted UNITED KINGDOM (NABPS) SRK Vidyalaya Post, Coimbatore 641 020, Tamil Nadu, INDIA [email protected] [email protected] Arnt Holte INTERNATIONAL P.O. -

Orbit Reader 20™ in User Guide

PROPRIETARY INFORMATION Orbit Reader 20™ IN User Guide 10th December 2018 Version 1.6 Orbit Reader 20 – User guide Version 1.6 Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 5 2 HOW THE ORBIT READER 20 IS USED ---------------------------------------------------------------- 5 2.1 STAND-ALONE MODE ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 2.2 REMOTE MODE--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 3 TRANSCRIBED BRAILLE ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 4 AUTOMATIC TRANSLATION ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 5 TRANSLATE BRAILLE --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 6 DOCUMENTATION CONVENTIONS --------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 7 IN THE BOX ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 8 8 FEATURES ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 9 ORIENTATION -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 9.1 KEY PLACEMENTS AND USE ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 9.2 PANNING KEYS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Guidance for the Transition to Unified English Braille

THE STATE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT I THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK I ALBANY, NY 12234 OFFICE OF SPECIAL EDUCATION ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER 89 Washington Avenue, Room 301 M EB • Albany, NY 12234 Telephone (518) 402·3353 www.pl2.nysed.gov/speciaied/ Fax: (518) 402·3534 October 2015 Special Education Field Advisory From: James P. DeLorenzeQ\Jl'l.J,._~ i<J;:}o ~ Subject: Guidance for the Transition to Unified English Braille The purpose of this memorandum is to provide information to school personnel regarding their responsibilities for preparing students who use English Braille American Edition (EBAE) to transition to Unified English Braille (UEB) as well as to provide resources for teachers for professional development. Instruction in UEB should begin as soon as possible during the 2015-2016 school year. Use of Music Braille and Nemeth code for math, science and technical subjects should be continued. In 2012, the Braille Authority of North America (BANA) voted to adopt UEB to replace EBAE in the United States, effective January 4, 2016. The project that led to the development of UEB was initiated in 1991 in an effort to preserve the use of braille worldwide. As of this "effective" date, UEB, Nemeth, Music, and the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) will be the official braille codes for use in the United States. Materials that have been produced in other braille codes prior to the 2016 UEB implementation date will remain in circulation. For many individuals who are blind and visually impaired, braille is necessary for the development of literacy. Students, teachers, braille transcribers, and parents and family members of individuals who read braille will need to learn UEB or update their knowledge of braille to include the rules governing UEB. -

Transliteration of Digital Gujarati Mathematical Text Into Braille for Visually Impaired People

International Journal endsof Latest in Engineering Tr and Technology Vol.(7)Issue(3), pp. 217-229 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21172/1.73.531 e-ISSN:2278-621X Transliteration of Digital Gujarati Mathematical Text into Braille for Visually Impaired People Nikisha B. Jariwala1 and Dr. Bankim Patel2 Abstract-Due to the limited availability of resources, particularly literatures in Braille text, visually impaired people are usually away from main stream of the society. Many researchers have worked on converting regular regional language text into Braille text. However, most of them have not given enough attention towards mathematical symbols/ notations. The approach discussed in this paper transliterates digital Gujarati mathematical text into Braille text that can also be stored as text file and can be printed on the Braille printer. The methodology employed in the proposed work is developed by considering standard Braille system American Grade 0. Rules are built according to the mathematical operators and transformation table is also created. The system shows satisfactory result. Keywords – Braille Script, Gujarati Language, Text-to-Braille (TTB), Digital Mathematical Text, Text processing, Mapping Technique I. INTRODUCTION In the world of Information Technology, where new researches, developments and inventions are witnessed in each and every field, many computer based systems are becoming available to assist people with disabilities. People with visual impairment are an integral part of the society and they can play a very significant role in the development. So if system is provided to them then it will become an aid for them in communication and interaction with sighted people. Touch and hearing are the two major senses well developed in visually impaired people then in sighted people.