What Does Chaos Theory Have to Do with Art?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of David Lynch

The Art of David Lynch weil das Kino heute wieder anders funktioniert; für ei- nen wie ihn ist da kein Platz. Aber deswegen hat Lynch ja nicht seine Kunst aufgegeben, und nicht einmal das Filmen. Es ist nur so, dass das Mainstream-Kino den Kaperversuch durch die Kunst ziemlich fundamental abgeschlagen hat. Jetzt den Filmen von David Lynch noch einmal wieder zu begegnen, ist ein Glücksfall. Danach muss man sich zum Fernsehapparat oder ins Museum bemühen. (Und grimmig die Propaganda des Künstlers für den Unfug transzendentaler Meditation herunterschlucken; »nobody is perfect.«) Was also ist das Besondere an David Lynch? Seine Arbeit geschah und geschieht nach den »Spielregeln der Kunst«, die bekanntlich in ihrer eigenen Schöpfung und zugleich in ihrem eigenen Bruch bestehen. Man er- kennt einen David-Lynch-Film auf Anhieb, aber niemals David Lynch hat David Lynch einen »David-Lynch-Film« gedreht. Be- 21 stimmte Motive (sagen wir: Stehlampen, Hotelflure, die Farbe Rot, Hauchgesänge von Frauen, das industrielle Rauschen, visuelle Americana), bestimmte Figuren (die Frau im Mehrfachleben, der Kobold, Kyle MacLachlan als Stellvertreter in einer magischen Biographie - weni- ger, was ein Leben als vielmehr, was das Suchen und Was ist das Besondere an David Lynch? Abgesehen Erkennen anbelangt, Väter und Polizisten), bestimmte davon, dass er ein paar veritable Kultfilme geschaffen Plot-Fragmente (die nie auflösbare Intrige, die Suche hat, Filme, wie ERASERHEAD, BLUE VELVET oder die als Sturz in den Abgrund, die Verbindung von Gewalt TV-Serie TWIN PEAKS, die aus merkwürdigen Gründen und Design) kehren in wechselnden Kompositionen (denn im klassischen Sinn zu »verstehen« hat sie ja nie wieder, ganz zu schweigen von Techniken wie dem jemand gewagt) die genau richtigen Bilder zur genau nicht-linearen Erzählen, dem Eindringen in die ver- richtigen Zeit zu den genau richtigen Menschen brach- borgenen Innenwelten von Milieus und Menschen, der ten, und abgesehen davon, dass er in einer bestimmten Grenzüberschreitung von Traum und Realität. -

David Cronenberg Et Howard Shore. Bref Portrait D'une Longue

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 00:20 Revue musicale OICRM David Cronenberg et Howard Shore. Bref portrait d’une longue collaboration Solenn Hellégouarch Une relève Résumé de l'article Volume 2, numéro 2, 2015 Après 45 ans de carrière, la filmographie de David Cronenberg compte 22 films, dont 15 ont été musicalisés par Howard Shore, qui a rejoint l’équipe du URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1060132ar cinéaste en 1979. Si l’univers cronenbergien est aujourd’hui bien connu, DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1060132ar l’apport de son compositeur demeure peu exploré. Or, la musique semble y jouer un rôle de toute première importance, le compositeur étant impliqué très Aller au sommaire du numéro tôt dans le processus cinématographique. Cette implication précoce est indicatrice du rôle central qu’occupent Shore et sa musique : comment le définir ? Plutôt que de recourir à une analyse des fonctions de la musique au cinéma, cet article explore les processus de création qui lui donnent naissance. Éditeur(s) Cronenberg et Shore, qui ont « tout appris en commun », présentent ainsi des OICRM processus créateurs aux traits similaires, ou plus exactement des figures artistiques communes, ici exposées, les regroupant sous une seule vision artistique : l’autodidacte, l’expérimentateur, l’improvisateur, le ISSN peintre/sculpteur et l’artiste-artisan. 2368-7061 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Hellégouarch, S. (2015). David Cronenberg et Howard Shore. Bref portrait d’une longue collaboration. Revue musicale OICRM, 2(2), 96–114. https://doi.org/10.7202/1060132ar Tous droits réservés © Revue musicale OICRM, 2015 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. January 5, 2015 to Sun. January 11, 2015 Monday January 5, 2015 Tuesday January 6, 2015

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. January 5, 2015 to Sun. January 11, 2015 Monday January 5, 2015 5:30 PM ET / 2:30 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Gene Simmons Family Jewels Baltic Coasts Face Your Demons - While on tour in Amsterdam, Gene and Shannon spend some quality time The Bird Route - Every spring and autumn, thousands of migrating birds over the Western with a young fan writing a school report. Pomeranian bodden landscape deliver one of the most breathtaking nature spectacles. 6:30 PM ET / 3:30 PM PT 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT Gene Simmons Family Jewels Smart Travels Europe What Happens In Vegas... - Gene and Shannon get invited to the premiere of the new Cirque du Out of Rome - We leave the eternal city behind by way of the famous Apian Way to explore the Soleil show “Viva Elvis” in Las Vegas. environs of Rome. First it’s the majesty of Emperor Hadrian’s villa and lakes of the Alban Hills. Next, it’s south to the ancient seaport of Ostia, Rome’s Pompeii. Along the way we sample olive 7:30 PM ET / 4:30 PM PT oil, stop at the ancient’s favorite beach and visit a medieval hilltop town. Our own five star villa Gene Simmons Family Jewels is a retreat fit for an emperor. God Of Thund - An exhausted Shannon reaches her limit with Gene’s snoring and sends him packing to a sleep doctor. 9:30 AM ET / 6:30 AM PT The Big Interview Premiere Alan Alda - Hollywood’s Mr. -

January 2005 NEWSLETTER a N E N T E R T a I N M E N T I N D U S T R Y O R G a N I Z a T I O N

January 2005 NEWSLETTER A n E n t e r t a i n m e n t I n d u s t r y O r g a n i z a t i o n FILM Music Biz Quiz 50th Anniversary Randall Rumage As we enter the new year, it’s good to review some of the amazing musical The President’s contributions made in 2004 to movies, television programs, and soundtrack albums. It’s now the season of the Golden Globes, the Academy Awards and the Corner Grammy Awards, all of which help to remind us of the songs, the scores, and the people who make them come to life. See if your film music trivia knowledge is Michael R. Morris up to speed with this scientifically uncertified multiple choice quiz! The answers In December, the CCC celebrated are on page 5. the holidays with its annual party, again held at the ever-hospitable 1. According to Billboard, what was the top selling soundtrack album of 2004? Cafe Cordiale. While this meant a A. Spider-Man 2 - (Geffen/DreamWorks/Interscope) hiatus from our regular monthly pa- B. Tupac: Resurrection – (Amaru/Interscope) nels, the sold-out evening afforded C. The Passion Of The Christ – (Integrity/Sony Music) CCC members and friends a splendid D. Ray (Ray Charles) – (WMG Soundtracks/Atlantic/Rhino) opportunity to usher out 2004, rekin- dle old friendships, and - of course - 2. Connect these top 5 Hot Soundtrack Singles (according to Billboard’s 2004 musically schmooze. Special kudos to year-end edition) to the soundtracks or films in which they were embodied: James Leach for organizing the musi- cal portion of the party, and to Deb- A. -

ROGÉRIO FERRARAZ O Cinema Limítrofe De David Lynch Programa

ROGÉRIO FERRARAZ O cinema limítrofe de David Lynch Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC/SP) São Paulo 2003 PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO – PUC/SP Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica O cinema limítrofe de David Lynch ROGÉRIO FERRARAZ Tese apresentada à Banca Examinadora da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, como exigência parcial para obtenção do título de Doutor em Comunicação e Semiótica – Intersemiose na Literatura e nas Artes, sob a orientação da Profa. Dra. Lúcia Nagib São Paulo 2003 Banca Examinadora Dedicatória Às minhas avós Maria (em memória) e Adibe. Agradecimentos - À minha orientadora Profª Drª Lúcia Nagib, pelos ensinamentos, paciência e amizade; - Aos professores, funcionários e colegas do COS (PUC), especialmente aos amigos do Centro de Estudos de Cinema (CEC); - À CAPES, pelas bolsas de doutorado e doutorado sanduíche; - À University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), por me receber como pesquisador visitante, especialmente ao Prof. Dr. Randal Johnson, supervisor de meus trabalhos no exterior, e aos professores, funcionários e colegas do Department of Spanish and Portuguese, do Department of Film, Television and Digital Media e do UCLA Film and Television Archives; - A David Lynch, pela entrevista concedida e pela simpatia com que me recebeu em sua casa; - Ao American Film Institute (AFI), pela atenção dos funcionários e por disponibilizar os arquivos sobre Lynch; - Aos meus amigos de ontem, hoje e sempre, em especial ao Marcus Bastos e à Maite Conde, pelas incontáveis discussões sobre cinema e sobre a obra de Lynch; - E, claro, a toda minha família, principalmente aos meus pais, Claudio e Laila, pelo amor, carinho, união e suporte – em todos os sentidos. -

Adventures in Film Music Redux Composer Profiles

Adventures in Film Music Redux - Composer Profiles ADVENTURES IN FILM MUSIC REDUX COMPOSER PROFILES A. R. RAHMAN Elizabeth: The Golden Age A.R. Rahman, in full Allah Rakha Rahman, original name A.S. Dileep Kumar, (born January 6, 1966, Madras [now Chennai], India), Indian composer whose extensive body of work for film and stage earned him the nickname “the Mozart of Madras.” Rahman continued his work for the screen, scoring films for Bollywood and, increasingly, Hollywood. He contributed a song to the soundtrack of Spike Lee’s Inside Man (2006) and co- wrote the score for Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007). However, his true breakthrough to Western audiences came with Danny Boyle’s rags-to-riches saga Slumdog Millionaire (2008). Rahman’s score, which captured the frenzied pace of life in Mumbai’s underclass, dominated the awards circuit in 2009. He collected a British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Award for best music as well as a Golden Globe and an Academy Award for best score. He also won the Academy Award for best song for “Jai Ho,” a Latin-infused dance track that accompanied the film’s closing Bollywood-style dance number. Rahman’s streak continued at the Grammy Awards in 2010, where he collected the prize for best soundtrack and “Jai Ho” was again honoured as best song appearing on a soundtrack. Rahman’s later notable scores included those for the films 127 Hours (2010)—for which he received another Academy Award nomination—and the Hindi-language movies Rockstar (2011), Raanjhanaa (2013), Highway (2014), and Beyond the Clouds (2017). -

Angelo Badalamenti Soundtrack from Twin Peaks Mp3, Flac, Wma

Angelo Badalamenti Soundtrack From Twin Peaks mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Jazz / Stage & Screen Album: Soundtrack From Twin Peaks Country: Ukraine Released: 1995 Style: Lounge, Post-Modern, Future Jazz, Soundtrack, Score, Post Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1262 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1477 mb WMA version RAR size: 1524 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 370 Other Formats: MP4 APE MP3 ASF VOX ADX FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Twin Peaks Theme A2 Laura Palmer's Theme A3 Audrey's Dance The Nightingale A4 Lyrics By – David LynchMixed By – Jay HealyVocals – Julee Cruise A5 Freshly Squeezed A6 The Bookhouse Boys Into The Night B1 Lyrics By – David LynchMixed By – Jay HealyVocals – Julee Cruise B2 Night Life In Twin Peaks B3 Dance Of The Dream Man B4 Love Theme From Twin Peaks Falling B5 Lyrics By – David LynchMixed By – Jay HealyVocals – Julee Cruise Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Warner Bros. Records Inc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – WEA International Inc. Copyright (c) – Warner Bros. Records Inc. Copyright (c) – WEA International Inc. Copyright (c) – Lynch/Frost Productions Inc. Credits A&R [Coordination] – Kevin Laffey Art Direction, Design – Tom Recchion Composed By – Angelo Badalamenti Coordinator [Soundtrack Album Coordination By Agm Management] – Tony Meilandt Drums – Grady Tate Electric Guitar [Electric Guitars] – Eddie Dixon, Vinnie Bell Flute, Clarinet – Eddie Daniels Mastered By – Howie Weinberg Mixed By – Art Pohlemus* (tracks: A1 to A3, A5, A6, B2 to B4) Orchestrated By, Arranged By – Angelo Badalamenti Photography By – Craig Sjodin, David Lynch, Fredrik Nilsen, Kimberly Wright, Marc Sirinsky, Paula K. Shimatsu-U Producer – Angelo Badalamenti, David Lynch Recorded By – Art Pohlemus* Synthesizer – Kinny Landrum Synthesizer, Piano – Angelo Badalamenti Tenor Saxophone, Clarinet, Flute – Al Regni* Notes Trade mark and recording licensed to P.T. -

Šablona -- Závěrečná Práce

Ohebnost zvuku ve filmové tvorbě Davida Lynche Ann Kuznetzova Bakalářská práce 2020 ABSTRAKT Tato práce se zaměřuje na analýzu zvukové tvorby Davida Lynche, především filmové, na příkladu jeho audiovizuálních děl Mazací hlava, Příběh Alvina Straighta, Inland Empire a jejich srovnání. Zabývá se způsobem ztvárnění idejí a určením charakteru zvukové tvorby Davida Lynche. Hlavním cílem je zjistit, do jaké míry je podstatná a v čem spočívá její určující dominantní vlastnost – ohebnost, a také prozkoumat vliv jiných druhů umění, osob, prostředí a událostí, které tvůrce dovedly k vlastnímu uměleckému sebevyjádření prostřednictvím zvuku. Obsahuje také rozhovor se zvukovým inženýrem Johnem Neffem, který se podělil o svoji zkušenost ze spolupráce s Lynchem. Klíčová slova: David Lynch, filmový zvuk, filmová hudba, Mazací hlava, Příběh Alvina Straighta, Inland Empire, Angelo Badalamenti, Alan Splet, Dean Hurley, John Neff ABSTRACT This Bachelor thesis focuses on the soundtrack in the cinematography of David Lynch with its primary goal of analyzing and comparing films of his authorship, in particular Eraserhead, The Straight Story, and Inland Empire. This thesis examines David Lynch’s creative process and establish the essence of his sound design. The aim is to determine wherein lies – and how major of a role plays – the dominant characteristic of David Lynch’s work, its versatility, as well as to explore how the environment, society, and different fields of art influenced the filmmaker in his own artistic expression through the language of sound. To further help answering those questions, an interview with a sound engineer, John Neff, was conducted, in which he talked about his experience of collaborating with David Lynch on several projects. -

Download the Digital Booklet

ELMER BERNSTEIN NICHOLAS BRITELL 01 World Soundtrack Awards Fanfare 1:33 09 Succession (Suite) 4:25 JAMES NEWTON HOWARD MYCHAEL DANNA 02 Red Sparrow Overture 6:36 10 Monsoon Wedding (Suite) 3:15 CARTER BURWELL ALEXANDRE DESPLAT 03 Fear - Main Title 2:32 11 The Imitation Game (Suite) 4:33 ALBERTO IGLESIAS PATRICK DOYLE 04 Hable con ella - Soy Marco 2:17 12 Murder on the Orient Express - Never Forget (Instrumental Version) 4:12 ELLIOT GOLDENTHAL 05 Cobb - The Homecoming 6:16 MICHAEL GIACCHINO 13 Star Trek, into Darkness and Beyond (Suite) 7:23 GABRIEL YARED 06 Troy (Suite) 5:19 ANGELO BADALAMENTI 14 Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me - JÓHANN JÓHANNSSON / The Voice of Love 4:02 RUTGER HOEDEMAEKERS 07 When at Last the Wind Lulled 2:13 JOHN WILLIAMS (Arr.) 15 Tribute to the Film Composer 4:25 JOHN WILLIAMS 08 Hook - The Face of Pan 4:06 Performed by BRUSSELS PHILHARMONIC & VLAAMS RADIOKOOR Conducted by DIRK BROSSÉ TWENTY YEARS OF WORLD SOUNDTRACK AWARDS Twenty years ago the World Soundtrack Academy scores achieved an afterlife and gained new handed out the very first World Soundtrack meaning as the result of live performances in Awards. They have since become of paramount front of audiences. Film Fest Ghent has made it importance across the industry. The awards did their point of honour to perpetuate that afterlife not only strengthen Film Fest Ghent’s identity, in Ghent in a series of albums. they have been a composer’s stepping stone to the Oscars, Golden Globes and BAFTAS. If To celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the Europe is now the metropolis of film music, then WSA, the album consists of compositions by Ghent has been the inspiration for it. -

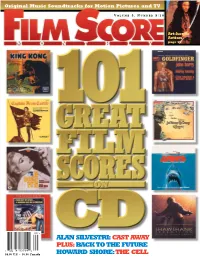

Back to the Future Howard Shore:The Cell

Original Music Soundtracks for Motion Pictures and TV V OLUME 5 , N UMBER 9 / 1 0 Art-house Action page 45 09 > ALAN SILVESTRI: CAST AWAY PLUS: BACK TO THE FUTURE 7 252 74 9 3 7 0 4 2 $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada HOWARD SHORE: THE CELL Two new scores by the legendary composer of The Mission and A Fistful Of Dollars. GAUMONT AND LEGenDE enTrePriSES PReSENT Also Available: The Mission Film Music Vol. I Film Music Vol. II MUSicic BYBY ENNIO MORRICONE a ROLAND JOFFÉ film IN STORES FEBRUARY 13 ©2001 Virgin Records America, Inc. v CONTENTS NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2000 cover story departments 26 101 Great Film Scores on CD 2 Editorial Here at the end of the year, century, millennium, Counting the Votes. whatever—FSM sticks out its collective neck and selects the ultimate list of influential, significant 4 News and enjoyable soundtracks released on CD. Hoyt Curtin, 1922-2000; By Joe Sikoryak, with John Bender, Jeff Bond, Winter Awards Winners. Jason Comerford, Tim Curran, Jeff Eldridge, 5 Record Label Jonathan Z. Kaplan, Lukas Kendall Round-up & Chris Stavrakis What’s on the way. 6 Now Playing 33 21 Should’a Been Contenders Movies and CDs in release. Go back to Back to the Future for 41 Missing in Action 8 Concerts ’round-the-clock analysis. Live performances page 16 around the world. f e a t u r e s 9 Upcoming Assignments 14 To Score or Not To Score? Who’s writing what Composer Alan Silvestri found his music for whom. struggling for survival in the post-production of Cast Away. -

Church of St. Ephrem 929 Bay Ridge Parkway ⬧ Brooklyn, New York 11228 Stephrembklyn Stephremparish-Brooklyn

Church of St. Ephrem 929 Bay Ridge Parkway ⬧ Brooklyn, New York 11228 www.stephremparish-brooklyn.org stephrembklyn stephremparish-brooklyn Parish Staff October 18, 2020 Twenty-Nineth Sunday in Ordinary Time Very Rev. Robert B. Adamo, V. F., KCHS, Pastor Rev. Msgr. Peter V. Kain, Pastor Emeritus Rev. Anthony S. Chanan, Parochial Vicar Mr. Robert Cote, Youth Minister Mrs. Michele James, Business Manager Rev. Msgr. Theophilus Joseph, Parochial Vicar Sr. Mary Ann Ambrose, C.S.J., Director of Faith Formation Mr. Thomas Marchesiello, Director of Music/Liturgy Deacon Kevin McLaughlin, Permanent Deacon Mr. Craig Mercado, Academy Principal Sr. Ann Martha Ondreicka, O.P., Director of the Spirituality Center Mrs. Lisa Pinsky, Parish Secretary Deacon Anthony Stucchio, Permanent Deacon Faith Formation Office Rectory Office Spirituality Center Third Floor of Academy 935 Bay Ridge Parkway 929 Bay Ridge Parkway 718-745-7486 718-833-1010 718-921-9518 [email protected] Online registration for Faith Fax 718-921-5232 Formation Class through the Parish Website St. Ephrem Catholic Academy 924 74th Street, Brooklyn, New York 11228 ⧫718-833-1440 ⧫ www.stephremcatholicacademy.org Schedule of Masses Saturday Vigil 5:00 PM Baptism Sunday 8:00 AM, 10:00 AM, 12 Noon and 5:00 PM Parents should call the rectory to make an appointment. Weekdays Monday through Friday 7:00 AM & 8:45 AM Please note that there are no baptisms during the season of Saturday 8:45 AM Lent. Rectory Office Hours Marriage Monday—Thursday: 9:00 AM—12 Noon The Sacrament of Marriage requires a time of serious spiritual 1:00 PM—5:00 PM preparation. -

Darkness Audible: Sub-Bass, Tape Decay and Lynchian Noise

186 ‘The grainy, staticky noise of Eraserhead.’ | LISA CLAIRE MAGEE DARKNESS AUDIBLE: Sub-bass, tape decay and Lynchian noise FRANCES MORGAN Noise is the forest of everything. The existence of noise implies a mutable world through an unruly intrusion of an other, an other that attracts difference, heterogeneity and productive confusion; moreover it implies a genesis of mutability itself. —Douglas Kahn1 DREAMING IN THE BLACK LODGE FEATURING 187 In the interests of research, I undertake Death a Twin Peaks marathon, from the iconic Dread first eight episodes to the end of season Drone two. Afterwards, I dream I am lost Distortion in a dark, airy house, populated with indistinct presences. Like Dale Cooper Doom metal making his multiple ways in and out of each curtained alcove, I become increasingly confused, roaming through 1 Douglas Kahn, Noise Water Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts (M I T, 1999), p.22. The End | AN ELECTRIC SHEEP ANTHOLOGY long rooms that change in shape and size. I can hear a voice, distorted, slowed down and incomprehensible: as the register sinks lower, the house’s darkness becomes more oppressive. Fear hums like a vast machine that operates almost below audible range but whose vibrations are felt in the feet and chest; death and decay take aural shape in rumble, static and hiss. This is not the actual sound of David Lynch’s Black Lodge, of course. Twin Peaks’ sound design reflects the restrictions imposed by television, which has a smaller dynamic range than film, and the series’ abiding sonic impressions, for most, are the constant presence of Angelo Badalamenti’s score, followed by the creative use of the voice, such as the backwards/forwards dialogue used by characters in Cooper’s dreams or visions.