Chrysippus's Dog As a Case Study in Non-Linguistic Cognition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cephalopods and the Evolution of the Mind

Cephalopods and the Evolution of the Mind Peter Godfrey-Smith The Graduate Center City University of New York Pacific Conservation Biology 19 (2013): 4-9. In thinking about the nature of the mind and its evolutionary history, cephalopods – especially octopuses, cuttlefish, and squid – have a special importance. These animals are an independent experiment in the evolution of large and complex nervous systems – in the biological machinery of the mind. They evolved this machinery on a historical lineage distant from our own. Where their minds differ from ours, they show us another way of being a sentient organism. Where we are similar, this is due to the convergence of distinct evolutionary paths. I introduced the topic just now as 'the mind.' This is a contentious term to use. What is it to have a mind? One option is that we are looking for something close to what humans have –– something like reflective and conscious thought. This sets a high bar for having a mind. Another possible view is that whenever organisms adapt to their circumstances in real time by adjusting their behavior, taking in information and acting in response to it, there is some degree of mentality or intelligence there. To say this sets a low bar. It is best not to set bars in either place. Roughly speaking, we are dealing with a matter of degree, though 'degree' is not quite the right term either. The evolution of a mind is the acquisition of a tool-kit for the control of behavior. The tool-kit includes some kind of perception, though different animals have very different ways of taking in information from the world. -

"Higher" Cognition. Animal Sentience

Animal Sentience 2017.030: Vallortigara on Marino on Thinking Chickens Sentience does not require “higher” cognition Commentary on Marino on Thinking Chickens Giorgio Vallortigara Centre for Mind/Brain Sciences University of Trento, Italy Abstract: I agree with Marino (2017a,b) that the cognitive capacities of chickens are likely to be the same as those of many others vertebrates. Also, data collected in the young of this precocial species provide rich information about how much cognition can be pre-wired and predisposed in the brain. However, evidence of advanced cognition — in chickens or any other organism — says little about sentience (i.e., feeling). We do not deny sentience in human beings who, because of cognitive deficits, would be incapable of exhibiting some of the cognitive feats of chickens. Moreover, complex problem solving, such as transitive inference, which has been reported in chickens, can be observed even in the absence of any accompanying conscious experience in humans. Giorgio Vallortigara, professor of Neuroscience at the Centre for Mind/Brain Sciences of the University of Trento, Italy, studies space, number and object cognition, and brain asymmetry in a comparative and evolutionary perspective. The author of more than 250 scientific papers on these topics, he was the recipient of several awards, including the Geoffroy Saint Hilaire Prize for Ethology (France) and a Doctor Rerum Naturalium Honoris Causa for outstanding achievements in the field of psychobiology (Ruhr University, Germany). r.unitn.it/en/cimec/abc In a revealing piece in New Scientist (Lawler, 2015a) and a beautiful book (Lawler, 2015b), science journalist Andrew Lawler discussed the possible consequences for humans of the sudden disappearance of some domesticated species. -

The Cognitive Animal : Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives on Animal Cognition

Contents Introduction ix 11 Learning and Memory Without a Contributors xvii Brain 77 James W. Grau THE DIVERSITY OF 12 Cognitive Modulation of Sexual COGNITION Behavior 89 Michael Domjan The Inner Life of Earthworms: Darwin's Argument and Us 13 Cognition and Emotion in Concert Implications 3 in Human and Nonhuman Animals 97 Eileen Crist Ruud van den Bos, Bart B. Houx, and Berry M. Spruijt 2 Crotalomorphism: A Metaphor for U nderstanding Anthropomorphism 14 Constructing Animal Cognition 105 by Omission 9 William Timberlake Jesús Rivas and Gordon M. 15 Genetics, Plasticity, and the Burghardt Evolution of Cognitive Processes 115 3 The Cognitive Defender: How Gordon M. Burghardt Ground Squirrels Assess Their 16 Spatial Behavior, Food Storing, and Predators 19 the Modular Mind 123 Donald H. Owings Sara J. Shettleworth 4 Jumping Spider Tricksters: Deceit, 17 Spatial and Social Cognition in Predation, and Cognition 27 Corvids: An Evolutionary Approach 129 Stim Wilcox and Robert Jackson Russell P. Balda and Alan C. 5 The Ungulate Mind 35 Kamil John A. Byers 18 Environmental Complexity, Signal 6 Can Honey Bees Create Cognitive Detection, and the Evolution of Maps? 41 Cognition 135 James L. Gould Peter Godfrey-Smith 7 Raven Consciousness 47 19 Cognition as an Independent Bernd Heinrich Variable: Virtual Ecology 143 Alan C. Kamil and Alan B. Bond 8 Animal Minds, Human Minds 53 Eric Saidel 20 Synthetic Ethology: A New Tool for Investigating Animal Cognition 151 9 Comparative Developmental Bruce MacLennan Evolutionary Psychology and Cognitive Ethology: Contrasting but 21 From Cognition in Animals to Compatible Research Programs 59 Cognition in Superorganisms 157 Sue Taylor Parker Charles E. -

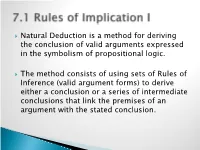

7.1 Rules of Implication I

Natural Deduction is a method for deriving the conclusion of valid arguments expressed in the symbolism of propositional logic. The method consists of using sets of Rules of Inference (valid argument forms) to derive either a conclusion or a series of intermediate conclusions that link the premises of an argument with the stated conclusion. The First Four Rules of Inference: ◦ Modus Ponens (MP): p q p q ◦ Modus Tollens (MT): p q ~q ~p ◦ Pure Hypothetical Syllogism (HS): p q q r p r ◦ Disjunctive Syllogism (DS): p v q ~p q Common strategies for constructing a proof involving the first four rules: ◦ Always begin by attempting to find the conclusion in the premises. If the conclusion is not present in its entirely in the premises, look at the main operator of the conclusion. This will provide a clue as to how the conclusion should be derived. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in the consequent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via modus ponens. ◦ If the conclusion contains a negated letter and that letter appears in the antecedent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining the negated letter via modus tollens. ◦ If the conclusion is a conditional statement, consider obtaining it via pure hypothetical syllogism. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a disjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via disjunctive syllogism. Four Additional Rules of Inference: ◦ Constructive Dilemma (CD): (p q) • (r s) p v r q v s ◦ Simplification (Simp): p • q p ◦ Conjunction (Conj): p q p • q ◦ Addition (Add): p p v q Common Misapplications Common strategies involving the additional rules of inference: ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a conjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via simplification. -

Emily Elizabeth Bray [email protected] [email protected]

Emily Elizabeth Bray www.emilyebray.com [email protected] [email protected] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE University of Arizona, School of Anthropology, Tucson, AZ and May 2017 – Present Canine Companions for Independence®, Santa Rosa, CA Post-doctoral Research Associate Focus: Longitudinal cognitive and behavioral studies in assistance dogs Supervisors: Dr. Evan MacLean and Dr. Brenda Kennedy EDUCATION University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA May 2017 PhD in Psychology (Concentration in Animal Learning and Behavior) Center for Teaching & Learning Teaching Certificate in College and University Teaching Dissertation: “A longitudinal study of maternal style, young adult temperament and cognition, and program outcome in a population of guide dogs” Advisors: Dr. Robert Seyfarth, Dr. Dorothy Cheney, and Dr. James Serpell University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA May 2013 M.A. in Psychology Thesis: “Dogs as a model system for understanding problem-solving: Exploring the affective and cognitive mechanisms that impact inhibitory control” Advisors: Dr. Robert Seyfarth, Dr. Dorothy Cheney, and Dr. James Serpell Duke University, Durham, NC May 2012 B.A. in Cognitive Psychology and English (summa cum laude), Graduation with Distinction in Psychology Psychology GPA 4.0, Cumulative GPA 3.97 Graduation with Distinction Thesis: “Factors Affecting Inhibitory Control in Dogs” Advisors: Dr. Brian Hare and Dr. Stephen Mitroff University College London, London, UK August 2010 - December 2010 Semester Abroad through Butler University’s Institute for Study Abroad PEER-REVIEWED PUBLICATIONS 10. Bray, E.E., Gruen, M.E., Gnanadesikan, G.E., Horschler, D.J., Levy, K. M., Kennedy, B.S., Hare, B.A., & MacLean, E.L. (in press). Dog cognitive development: a longitudinal study across the first two years of life. -

Comparative Evolutionary Approach to Pain Perception in Fishes

Brown, Culum (2016) Comparative evolutionary approach to pain perception in fishes. Animal Sentience 3(5) DOI: 10.51291/2377-7478.1029 This article has appeared in the journal Animal Sentience, a peer-reviewed journal on animal cognition and feeling. It has been made open access, free for all, by WellBeing International and deposited in the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Animal Sentience 2016.011: Brown Commentary on Key on Fish Pain Comparative evolutionary approach to pain perception in fishes Commentary on Key on Fish Pain Culum Brown Biological Sciences Macquarie University Abstract: Arguments against the fact that fish feel pain repeatedly appear even in the face of growing evidence that they do. The standards used to judge pain perception keep moving as the hurdles are repeatedly cleared by novel research findings. There is undoubtedly a vested commercial interest in proving that fish do not feel pain, so the topic has a half-life well past its due date. Key (2016) reiterates previous perspectives on this topic characterised by a black-or-white view that is based on the proposed role of the human cortex in pain perception. I argue that this is incongruent with our understanding of evolutionary processes. Keywords: pain, fishes, behaviour, physiology, nociception Culum Brown [email protected] studies the behavioural ecology of fishes with a special interest in learning and memory. He is Associate Professor of vertebrate evolution at Macquarie University, Co-Editor of the volume Fish Cognition and Behavior, and Editor for Animal Behaviour of the Journal of Fish Biology. -

Chapter Two Democritus and the Different Limits to Divisibility

CHAPTER TWO DEMOCRITUS AND THE DIFFERENT LIMITS TO DIVISIBILITY § 0. Introduction In the previous chapter I tried to give an extensive analysis of the reasoning in and behind the first arguments in the history of philosophy in which problems of continuity and infinite divisibility emerged. The impact of these arguments must have been enormous. Designed to show that rationally speaking one was better off with an Eleatic universe without plurality and without motion, Zeno’s paradoxes were a challenge to everyone who wanted to salvage at least those two basic features of the world of common sense. On the other hand, sceptics, for whatever reason weary of common sense, could employ Zeno-style arguments to keep up the pressure. The most notable representative of the latter group is Gorgias, who in his book On not-being or On nature referred to ‘Zeno’s argument’, presumably in a demonstration that what is without body and does not have parts, is not. It is possible that this followed an earlier argument of his that whatever is one, must be without body.1 We recognize here what Aristotle calls Zeno’s principle, that what does not have bulk or size, is not. Also in the following we meet familiar Zenonian themes: Further, if it moves and shifts [as] one, what is, is divided, not being continuous, and there [it is] not something. Hence, if it moves everywhere, it is divided everywhere. But if that is the case, then everywhere it is not. For it is there deprived of being, he says, where it is divided, instead of ‘void’ using ‘being divided’.2 Gorgias is talking here about the situation that there is motion within what is. -

Animal Cognition Research Offers Outreach Opportunity John Carey, Science Writer

SCIENCE AND CULTURE SCIENCE AND CULTURE Animal cognition research offers outreach opportunity John Carey, Science Writer In a classroom in Thailand, groups of elementary school human populations growing and wildlife habitat shrink- children are marching around large sheets of newspaper ing, there’s less room for people and animals. In Thai- on the floor. Music plays. Each group of five kids has a land, that’s led to increasing conflicts between newspaper sheet. When the music stops, the children crop-raiding elephants and farmers. These clashes rush to stand on their sheet. The first time, there’sroom go beyond the research realm, involving a complex for all. As music starts and stops, though, the teacher interplay of conservation, economics, and societal makes the newspaper sheet smaller and smaller. Eventu- concerns. So the scientist behind the exercise, ally, five pairs of feet can no longer fit on the sheet. Some Hunter College psychologist and elephant researcher of the children climb on their partners, cramming their Joshua Plotnik, figured he needed to branch out bodies together before tumbling to the ground laughing. beyond his fieldwork on elephant cognition and The children are having a great time. But this game find ways to use his research to help reduce those of “losing space” also has a serious message. With conflicts. “The fight to protect elephants and other Elephants can cooperate with one another by pulling simultaneously on both ends of the rope to gather food from a platform. Joshua Plotnik has sought to incorporate such results into education and conservation efforts. Image courtesy of Joshua Plotnik. -

Chapter 9: Answers and Comments Step 1 Exercises 1. Simplification. 2. Absorption. 3. See Textbook. 4. Modus Tollens. 5. Modus P

Chapter 9: Answers and Comments Step 1 Exercises 1. Simplification. 2. Absorption. 3. See textbook. 4. Modus Tollens. 5. Modus Ponens. 6. Simplification. 7. X -- A very common student mistake; can't use Simplification unless the major con- nective of the premise is a conjunction. 8. Disjunctive Syllogism. 9. X -- Fallacy of Denying the Antecedent. 10. X 11. Constructive Dilemma. 12. See textbook. 13. Hypothetical Syllogism. 14. Hypothetical Syllogism. 15. Conjunction. 16. See textbook. 17. Addition. 18. Modus Ponens. 19. X -- Fallacy of Affirming the Consequent. 20. Disjunctive Syllogism. 21. X -- not HS, the (D v G) does not match (D v C). This is deliberate to make sure you don't just focus on generalities, and make sure the entire form fits. 22. Constructive Dilemma. 23. See textbook. 24. Simplification. 25. Modus Ponens. 26. Modus Tollens. 27. See textbook. 28. Disjunctive Syllogism. 29. Modus Ponens. 30. Disjunctive Syllogism. Step 2 Exercises #1 1 Z A 2. (Z v B) C / Z C 3. Z (1)Simp. 4. Z v B (3) Add. 5. C (2)(4)MP 6. Z C (3)(5) Conj. For line 4 it is easy to get locked into line 2 and strategy 1. But they do not work. #2 1. K (B v I) 2. K 3. ~B 4. I (~T N) 5. N T / ~N 6. B v I (1)(2) MP 7. I (6)(3) DS 8. ~T N (4)(7) MP 9. ~T (8) Simp. 10. ~N (5)(9) MT #3 See textbook. #4 1. H I 2. I J 3. -

Argument Forms and Fallacies

6.6 Common Argument Forms and Fallacies 1. Common Valid Argument Forms: In the previous section (6.4), we learned how to determine whether or not an argument is valid using truth tables. There are certain forms of valid and invalid argument that are extremely common. If we memorize some of these common argument forms, it will save us time because we will be able to immediately recognize whether or not certain arguments are valid or invalid without having to draw out a truth table. Let’s begin: 1. Disjunctive Syllogism: The following argument is valid: “The coin is either in my right hand or my left hand. It’s not in my right hand. So, it must be in my left hand.” Let “R”=”The coin is in my right hand” and let “L”=”The coin is in my left hand”. The argument in symbolic form is this: R ˅ L ~R __________________________________________________ L Any argument with the form just stated is valid. This form of argument is called a disjunctive syllogism. Basically, the argument gives you two options and says that, since one option is FALSE, the other option must be TRUE. 2. Pure Hypothetical Syllogism: The following argument is valid: “If you hit the ball in on this turn, you’ll get a hole in one; and if you get a hole in one you’ll win the game. So, if you hit the ball in on this turn, you’ll win the game.” Let “B”=”You hit the ball in on this turn”, “H”=”You get a hole in one”, and “W”=”you win the game”. -

Passionate Platonism: Plutarch on the Positive Role of Non-Rational Affects in the Good Life

Passionate Platonism: Plutarch on the Positive Role of Non-Rational Affects in the Good Life by David Ryan Morphew A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in The University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Victor Caston, Chair Professor Sara Ahbel-Rappe Professor Richard Janko Professor Arlene Saxonhouse David Ryan Morphew [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-4773-4952 ©David Ryan Morphew 2018 DEDICATION To my wife, Renae, whom I met as I began this project, and who has supported me throughout its development. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I am grateful to my advisors and dissertation committee for their encouragement, support, challenges, and constructive feedback. I am chiefly indebted to Victor Caston for his comments on successive versions of chapters, for his great insight and foresight in guiding me in the following project, and for steering me to work on Plutarch’s Moralia in the first place. No less am I thankful for what he has taught me about being a scholar, mentor, and teacher, by his advice and especially by his example. There is not space here to express in any adequate way my gratitude also to Sara Ahbel-Rappe and Richard Janko. They have been constant sources of inspiration. I continue to be in awe of their ability to provide constructive criticism and to give incisive critiques coupled with encouragement and suggestions. I am also indebted to Arlene Saxonhouse for helping me to see the scope and import of the following thesis not only as of interest to the history of philosophy but also in teaching our students to reflect on the kind of life that we want to live. -

The Seven Sages.Pdf

Document belonging to the Greek Mythology Link, a web site created by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology Characters • Places • Topics • Images • Bibliography • PDF Editions About • Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. The Seven Sages of Greece Search the GML advanced Sections in this Page Introduction: The Labyrinth of Wisdom The Seven Sages of Greece Thales Solon Chilon Pittacus Bias "… wisdom is a form of goodness, and is not scientific knowledge but Cleobulus another kind of cognition." (Aristotle, Eudemian Ethics 1246b, 35). Periander Anacharsis Myson Epimenides Pherecydes Table: Lists of the Seven Sages Notes and Sources of Quotations Introduction: The Labyrinth of Wisdom For a god wisdom is perhaps a divine meal to be swallowed at one gulp without need of mastication, and that would be the end of the story. The deities are known for their simplicity. The matter of human wisdom, however, could fill all archives on earth without ever exhausting itself. Humanity is notorious for its complexity. And men proudly say "Good things are difficult." But is wisdom a labyrinth, or "thinking makes it so"? And when did the saga of human wisdom begin and with whom? The Poet When humans contemplated Dawn for the first time, wisdom was the treasure of the poet alone. Of all men he was the wisest, for the gods had chosen his soul as receptacle of their confidences. Thus filled with inspiration divine, the poet knew better than any other man the secrets of the world. And since Apollo found more pleasure in leading the Muses than in warming his tripod, neither the inspiration of the Pythia nor that of seers could match the poet's wisdom.