The Daraawiish Resistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

The Case of Somalia (1960-2001)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) State collapse and post-conflict development in Africa : the case of Somalia (1960-2001) Mohamoud, A. Publication date 2002 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Mohamoud, A. (2002). State collapse and post-conflict development in Africa : the case of Somalia (1960-2001). Thela Thesis. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:28 Sep 2021 Chapterr four Thee Pitfalls of Colonialism and Public Pursuit 4.1.. Introduction Thiss chapter traces how the change brought about by the colonial imposition led to the primacyy of the public pursuit in Somali politics over a century. The colonial occupation of Somaliaa not only transformed the political economy of Somali society as transformationists emphasizee but also split the Somali people and their territories.74 Therefore, as I will argue in thiss study, the multiple partitioning of the country is one of the key determinants that fundamentallyy account for the destructive turn of events in Somalia at present. -

CLAIMING the EASTERN BORDERLANDS After the 1997

CHAPTER SEVEN CLAIMING THE EASTERN BORDERLANDS After the 1997 Hargeysa Conference, the Somaliland state apparatus consolidated. It deepened, as the state realm displaced governance arrangements overseen by clan elders. And it broadened, as central government control extended geographically from the capital into urban centres such as Borama in the west and Bur’o in the east. In the areas east of Bur’o government was far less present or efffective, especially where non-Isaaq clans traditionally lived. Erigavo, the capital of Sanaag Region, which was shared by the Habar Yunis, the Habar Ja’lo, the Warsengeli and the Dhulbahante, was fijinally brought under formal government control in 1997, after Egal sent a delegation of nine govern- ment ministers originating from the area to sort out local government with the elders and political actors on the ground. After fijive months of negotiations, the president was able to appoint a Mayor for Erigavo and a Governor for Sanaag.1 But east of Erigavo, in the area inhabited by the Warsengeli, any claim to governance from Hargeysa was just nominal.2 The same was true for most of Sool Region inhabited by the Dhulbahante. Eastern Sanaag and Sool had not been Egal’s priority. The president did not strictly need these regions to be under his military control in order to preserve and consolidate his position politically or in terms of resources. The port of Berbera was vital for the economic survival of the Somaliland government. Erigavo and Las Anod were not. However, because the Somaliland government claimed the borders of the former British protec- torate as the borders of Somaliland, Sanaag and Sool had to be seen as under government control. -

Report of the Tsunami Inter Agency Assessment Mission, Hafun to Gara

TSUNAMI INTER AGENCY ASSESSMENT MISSION Hafun to Gara’ad Northeast Somali Coastline th th Mission: 28 January to 8 February 2005 2 Table of Content Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................................. 5 2. Introduction................................................................................................................................................. 12 2.1 Description of the Tsunami.............................................................................................................. 12 2.2 Description of the Northeast coastline............................................................................................. 13 2.3 Seasonal calendar........................................................................................................................... 14 2.4 Governance structures .................................................................................................................... 15 2.5 Market prices ................................................................................................................................... 16 2.6 UN Agencies and NGOs (local and international) on ground.......................................................... 16 3. Methodology ............................................................................................................................................... 17 4. Food, Livelihood & Nutrition Security Sector......................................................................................... -

Rethinking the Somali State

Rethinking the Somali State MPP Professional Paper In Partial Fulfillment of the Master of Public Policy Degree Requirements The Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs The University of Minnesota Aman H.D. Obsiye May 2017 Signature below of Paper Supervisor certifies successful completion of oral presentation and completion of final written version: _________________________________ ____________________ ___________________ Dr. Mary Curtin, Diplomat in Residence Date, oral presentation Date, paper completion Paper Supervisor ________________________________________ ___________________ Steven Andreasen, Lecturer Date Second Committee Member Signature of Second Committee Member, certifying successful completion of professional paper Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology .......................................................................................................................... 5 The Somali Clan System .......................................................................................................... 6 The Colonial Era ..................................................................................................................... 9 British Somaliland Protectorate ................................................................................................. 9 Somalia Italiana and the United Nations Trusteeship .............................................................. 14 Colonial -

Peace in Puntland: Mapping the Progress Democratization, Decentralization, and Security and Rule of Law

Peace in Puntland: Mapping the Progress Democratization, Decentralization, and Security and Rule of Law Pillars of Peace Somali Programme Garowe, November 2015 Acknowledgment This Report was prepared by the Puntland Development Re- search Center (PDRC) and the Interpeace Regional Office for Eastern and Central Africa. Lead Researchers Research Coordinator: Ali Farah Ali Security and Rule of Law Pillar: Ahmed Osman Adan Democratization Pillar: Mohamoud Ali Said, Hassan Aden Mo- hamed Decentralization Pillar: Amina Mohamed Abdulkadir Audio and Video Unit: Muctar Mohamed Hersi Research Advisor Abdirahman Osman Raghe Editorial Support Peter W. Mackenzie, Peter Nordstrom, Jessamy Garver- Affeldt, Jesse Kariuki and Claire Elder Design and Layout David Müller Printer Kul Graphics Ltd Front cover photo: Swearing-in of Galkayo Local Council. Back cover photo: Mother of slain victim reaffirms her com- mittment to peace and rejection of revenge killings at MAVU film forum in Herojalle. ISBN: 978-9966-1665-7-9 Copyright: Puntland Development Research Center (PDRC) Published: November 2015 This report was produced by the Puntland Development Re- search Center (PDRC) with the support of Interpeace and represents exclusively their own views. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the contribut- ing donors and should not be relied upon as a statement of the contributing donors or their services. The contributing donors do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor do they accept responsibility for any use -

Enhanced Enrolment of Pastoralists in the Implementation and Evaluation of the UNICEF-FAO-WFP Resilience Strategy in Somalia

Enhanced enrolment of pastoralists in the implementation and evaluation of the UNICEF-FAO-WFP Resilience Strategy in Somalia Prepared for UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) by Esther Schelling, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute UNICEF ESARO JUNE 2013 Enhanced enrolment of pastoralists in the implementation and evaluation of UNICEF-FAO-WFP Resilience Strategy in Somalia © United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Nairobi, 2013 UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) PO Box 44145-00100 GPO Nairobi June 2013 The report was prepared for UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) by Esther Schelling, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the policies or the views of UNICEF. The text has not been edited to official publication standards and UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this publication do not imply an opinion on legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. For further information, please contact: Esther Schelling, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, University of Basel: [email protected] Eugenie Reidy, UNICEF ESARO: [email protected] Dorothee Klaus, UNICEF ESARO: [email protected] Cover photograph © UNICEF/NYHQ2009-2301/Kate Holt 2 Table of Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

Between Somaliland and Puntland Marginalization, Militarization and Conflicting Political Visions

rift valley institute | Contested Borderlands Between Somaliland and Puntland Marginalization, militarization and conflicting political visions MARKUS VIRGIL HOEHNE rift VALLEY institute | Contested Borderlands Between Somaliland and Puntland Marginalization, militarization and conflicting political visions MarKus virGil HoeHne Published in 2015 by the Rift Valley Institute 26 St Luke’s Mews, London W11 1DF, United Kingdom PO Box 52771 GPO, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya tHe rift VALLEY institute (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in Eastern and Central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. tHe autHor Markus Virgil Hoehne is a lecturer in social anthropology at the University of Leipzig. This work is based on research he carried out during his time at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle/Saale, Germany. Between soMaliland and puntland The Rift Valley Institute takes no position on the status of Somaliland or Puntland. Views expressed in Between Somaliland and Puntland are those of the author. Boundaries shown on maps in this book are endorsed neither by the Rift Valley Institute, nor by the author. RVI exeCutive direCtor: John Ryle RVI Horn of afriCa and east afriCa reGional direCtor: Mark Bradbury RVI inforMation and proGraMMes adMINISTRATOR: Tymon Kiepe editorial ManaGeMent: Catherine Bond editors: Peter Fry and Fergus Nicoll report desiGn: Lindsay Nash Maps: Jillian Luff, MAPgrafix isBn 978-1-907431-13-5 Cover: Amina Abdulkadir The painting depicts the complexities of political belonging since the collapse of the Somali state in 1991. The yellow lines indicate the frontiers claimed by Somaliland and Puntland. The colour closest to gold portrays the contest for resources. -

Editorial: the Mad Mullah Revisited

Home | Contact us | Links | Archives | Search Issue 570-- 29th Dec 2012 - 4th Jan, 2013 Editorial: The Mad Mullah Revisited Abdirahman Farah ‘Barwaqo’s latest book “Sooyaal: Ina Cabdalla Xasan Ma Sheekh Bu Ahaa Mise…?” is on Muhammad Abdille Hassan and starts with an intriguing title. It asks the question whether Muhammad Abdille Hassan was a religious sheikh or something else. That something else is not spelled out in the title and is left to the reader to guess. The implication is that by reading the book one will find the answer. One however, does not have to get too far into reading the book to know the answer which is that Muhammad Abdille was far from being a sheikh, and was in fact a ruthless killer who consistently violated Islamic principles as well as basic human morality. Mr. Barwaaqo builds the case against Muhammad Abdille Hassan in a very methodical fashion beginning with showing how the people of Berbera initially welcomed him and helped him settle there but when he started making provocative claims and they found out that his religious knowledge was deficient they rejected him and that was why he left Berbera. Mr. Barwaqo also compares Muhammad Abdille Hassan with other Somali religious leaders and finds him wanting by showing that while Sheikh Madar and his fellow members of the Qadiriya Sufi order at Jameecoweyn laid the basis of the city of Hargeysa and established the first Somali city that was governed according to Islamic law, and while other religious leaders such as Yusuf al- Kawnayn, Sheikh Ibrahim Abdalle Mayal, Sheikh Muhammad Abdi Makahil, Sheikh Abdirahman Sheikh Nur, and Sheikh Uweys Bin Muhammad al-Barawi contributed to Somali knowledge by devising orthographies, Muhammad Abdille Hassan was busy bringing death and destruction to Somalis. -

Bajuni Clan.Pdf

Somalia - Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 13 November 2009 Information regarding the treatment of the Bajuni clan in Somalia The United Kingdom Home Office Operational Guidance Note for Somalia states: “Somalis with no clan affiliation are the most vulnerable to serious human rights violations, including predatory acts by criminal and militias, as well economic, political, cultural and social discrimination. These groups comprise an estimated 22% of the Somali population and include the Bajuni. The Bajuni are a small independent ethnic community of perhaps 3,000 or 4,000 who are predominantly sailors and fishermen. They live in small communities along the Indian Ocean coastline (including Somalia and Kenya) and on some of the larger offshore islands between Kismayo and Mombasa, Kenya. The small Bajuni population in Somalia suffered considerably at the hands of Somali militia, principally Marehan militia who tried to force them off the islands. Though Marehan settlers still have effective control of the islands, Bajuni can work for the Marehan as paid labourers. This is an improvement on the period during the 1990s when General Morgan’s forces controlled Kismayo and the islands, when the Bajuni were treated by the occupying Somali clans as little more than slave labour. Essentially the plight of the Bajuni is based on the denial of economic access by Somali clans, rather than outright abuse. Information provided by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in May 2008 about the fluid country situation following the ousting of the UIC indicates that the risk to personal safety for the vast majority of Somalis, whether affiliated to majority or minority clans, is the same and that there is little detectable difference between some individual circumstances. -

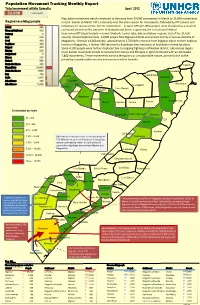

Population Movement Tracking Monthly Report

Population Movement Tracking Monthly Report Total movement within Somalia April 2012 33,000 nationwide Population movement trends continued to decrease from 39,000 movements in March to 33,000 movements Region receiving people in April. Similar to March 2012, insecurity was the main reason for movements, followed by IDP returns and Region People Awdal 400 temporary or seasonal cross border movements. In April, 65% (21,000 people) were displaced as a result of Woqooyi Galbeed 500 continued armed conflict between Al Shabaab and forces supporting the Transitional Federal Sanaag 0 Government(TFG) particularly in Lower Shabelle, Lower Juba, Bay and Bakool regions. Out of the 21,000 Bari 200 security related displacements, 14,000 people fled Afgooye district and arrived mainly in various districts of Sool 400 Mogadishu. Of these 14,000 people, approximately 3,700 IDPs returned from Afgooye closer to their habitual Togdheer 100 homes in Mogadishu, a further 590 returned to Baydhaba after cessation of hostilities in these locations. Nugaal 400 Some 4,100 people were further displaced due to ongoing fighting in Afmadow district, Juba Hoose region. Mudug 500 Cross border movement trends to Somalia from Kenya and Ethiopia in April continued with an estimated Galgaduud 0 2,800 movements. These movements are of a temporary or unsustainable nature, primarily due to the Hiraan 200 Bakool 400 prevailing unpredictable security environment within Somalia. Shabelle Dhexe 300 Caluula Mogadishu 20,000 Shabelle Hoose 1,000 Qandala Bay 700 Zeylac Laasqoray Gedo 3,200 Bossaso Juba Dhexe 100 Lughaye Iskushuban Juba Hoose 5,300 Baki Ceerigaabo Borama Berbera Ceel Afweyn Sheikh Gebiley Hargeysa Qardho Odweyne Bandarbeyla Burco Caynabo Xudun Taleex Estimated arrivals Buuhoodle Laas Caanood Garoowe 30 - 250 Eyl Burtinle 251 - 500 501 - 1,000 Jariiban Goldogob 1,001 - 2,500 IDPs who were displaced due to tensions between Gaalkacyo TFG-Allied forces and the Al Shabaab in Baydhaba 2,501 - 5,000 district continued to return. -

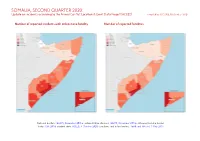

SOMALIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 30 October 2020

SOMALIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 30 October 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Ethiopia/Somalia border status: CIA, 2014; incident data: ACLED, 3 October 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SOMALIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 30 OCTOBER 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Battles 327 152 465 Conflict incidents by category 2 Violence against civilians 146 100 144 Development of conflict incidents from June 2018 to June 2020 2 Explosions / Remote 133 59 187 violence Methodology 3 Protests 28 1 1 Conflict incidents per province 4 Strategic developments 18 2 2 Riots 6 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 658 314 799 Disclaimer 6 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 3 October 2020). Development of conflict incidents from June 2018 to June 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 3 October 2020). 2 SOMALIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 30 OCTOBER 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known.