12.2% 125000 145M Top 1% 154 5000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evidence-Based Management of Suspected Appendicitis in The

October 2011 Evidence-Based Management Volume 13, Number 10 Of Suspected Appendicitis In Authors Michael Alan Cole, MD Associate Physician, Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham The Emergency Department and Women’s Hospital; Clinical Instructor, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA Nicholas Maldonado, MD Abstract Emergency Physician, Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Affiliated Emergency Medicine Residency, Boston, MA Appendicitis is the most common cause of acute abdominal pain requiring surgical treatment in persons under 50 years of age, Peer Reviewers with a peak incidence in the second and third decades. Women John Howell, MD, FACEP, FAAEM Clinical Professor of Emergency Medicine, The George Washington have a greater risk of misdiagnosis and a higher negative appen- University, Washington, DC; Director of Academics and Risk Management, dectomy rate. Atypical presentations of appendicitis are com- Best Practices, Inc., Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, VA monly misdiagnosed, resulting in increased morbidity, mortality, Christopher Strother, MD Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine and Pediatrics, Director, and potential litigation. The variability of presentation relates to Emergency and Undergraduate Simulation, Mount Sinai School of the varied anatomical location and the visceral innervation of the Medicine, New York, NY appendix. Patients presenting with possible appendicitis should Robert Vissers, MD, FACEP be risk stratified based on history, physical examination, and Chief, Emergency Medicine, Quality Director, Legacy Emanuel Hospital, Adjunct Associate Professor, Oregon Health & Science University School laboratory data. An elevated white blood cell (WBC) count alone of Medicine, Portland, OR (> 10,000 cells/mm3) offers poor diagnostic utility; however, CME Objectives combining WBC count > 10 and C-reactive protein (CRP) level > Upon completion of this article, you should be able to: 8 achieves notable predictive power in the diagnosis of acute ap- 1. -

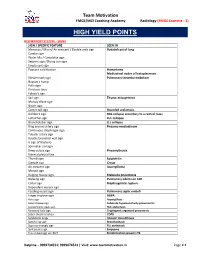

High Yield Points

Team Motivation FMGE/MCI Coaching Academy Radiology (FMGE Essentia - 3) HIGH YIELD POINTS RESPIRATORY SYSTEM – SIGNS SIGN / SPECIFIC FEATURE SEEN IN Meniscus / Moon/ Air crescent / Double arch sign Hydatid cyst of lung Cumbo sign Water lilly / Camalotte sign Serpent sign / Rising sun sign Empty cyst sign Popcorn calcification Hamartoma Mediastinal nodes of histoplasmosis Westermark sign Pulmonary thrombo-embolism Hapton’s hump Palla sign Fleishner lines Felson’s sign Sail sign Thymic enlargement Mulvay Wave sign Notch sign Comet tail sign Rounded atelectasis Golden S sign RUL collapse secondary to a central mass Luftsichel sign LUL collapse Broncholobar sign LLL collapse Ring around artery sign Pneumo-mediastinum Continuous diaphragm sign Tubular artery sign Double bronchial wall sign V sign of Naclerio Spinnaker sail sign Deep sulcus sign Pneumothorax Visceral pleural line Thumb sign Epiglottitis Steeple sign Croup Air crescent sign Aspergilloma Monod sign Bulging fissure sign Klebsiella pneumonia Batwing sign Pulmonary edema on CXR Collar sign Diaphragmatic rupture Dependant viscera sign Feeding vessel sign Pulmonary septic emboli Finger in glove sign ABPA Halo sign Aspergillosis Head cheese sign Subacute hypersensitivity pneumonitis Juxtaphrenic peak sign RUL atelectasis Reversed halo sign Cryptogenic organized pneumonia Saber sheath trachea COPD Sandstorm lungs Alveolar microlithiasis Signet ring sign Bronchiectasis Superior triangle sign RLL atelectasis Split pleura sign Empyema Tree in bud sign on HRCT Endobronchial spread in TB -

Acute Appendicitis: Hispanics and the Hamburger Sign

Research Article More Information *Address for Correspondence: Romero- Acute Appendicitis: Hispanics and the Vazquez Ana M, MS, Ponce Health and Sciences University, Ponce, Puerto Rico- School of Medicine, Puerto Rico, Tel: (787)363-6739; Hamburger Sign Email: [email protected]; [email protected] 1 1 1 Garcia Gubern C , Colon Rolón L , Ruiz Mercado I , Oliveras Submitted: 12 November 2019 Garcia C1, Caban Acosta D1, Muñoz Pagán J1, Iriarte I3, Bolaños Approved: 19 November 2019 Published: 20 November 2019 Ávila G2, Peguero Rivera J2, Sánchez Gaetan F2, Oneill Castro J2, 1 1 How to cite this article: Garcia Gubern C, Colon Cordero Colón Paola N , Garcia-Colon Carlos A and Romero- Rolón L, Ruiz Mercado I, Oliveras Garcia C, Caban 4 Vazquez Ana M * Acosta D, et al. Acute Appendicitis: Hispanics and the Hamburger Sign. Arch Surg Clin Res. 1 MD, Department of Emergency Medicine Hospital San Lucas, Ponce, Puerto Rico 2019; 3: 078-081. 2Department of Surgery Hospital San Lucas, Ponce, Puerto Rico DOI: dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.ascr.1001041 3Ponce Health and Sciences University, Ponce, School of Public Health, Puerto Rico ORCiD: orcid.org/0000-0001-7214-0748 4Ponce Health and Sciences University, Ponce, School of Medicine, Puerto Rico Copyright: © 2019 Garcia Gubern C, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, Abstract which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the Objective: To describe the presenting clinical fi ndings of patients with acute appendicitis and original work is properly cited. compare them with those described in the medical literature. -

Acute Appendicitis in Adults

International Surgery Journal Vagholkar K. Int Surg J. 2020 Sep;7(9):3180-3186 http://www.ijsurgery.com pISSN 2349-3305 | eISSN 2349-2902 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18203/2349-2902.isj20203822 Review Article Acute appendicitis in adults Ketan Vagholkar* Department of Surgery, D. Y. Patil University School of Medicine, Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra, India Received: 16 June 2020 Revised: 28 July 2020 Accepted: 03 August 2020 *Correspondence: Dr. Ketan Vagholkar, E-mail: [email protected] Copyright: © the author(s), publisher and licensee Medip Academy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Acute appendicitis is one of the commonest abdominal emergency encountered by a general surgeon. Understanding the surgical pathology is pivotal in identifying the stage of disease at which the patient presents for better correlation of clinical features, laboratory and imaging reports. Various scoring systems enhance and aid this process. Imaging confirms the diagnosis. Early diagnosis is essential to prevent complications. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment. Appendicitis may present in various forms in different clinical settings. A uniform approach to presentations may not always yield good results. Though appendectomy is the mainstay of treatment yet a tailor made surgical plan needs to be developed after holistic evaluation of the patient. The article discusses the differential surgical approach based on the etiopathogenesis, diagnosis and variable clinical presentations. Keywords: Acute appendicitis, Diagnosis, Scoring, Treatment INTRODUCTION decreased bowel transit time and reduces the formation of faecoliths, which lead to obstruction and initiation of the Acute appendicitis is one of the most common abdominal inflammatory cascade.2-4 The disease is more common in emergency managed by a general surgeon. -

Surgical Abdomen

GI module Jane R. Perlman Fellowship Program Nurse Practitioner and Physician Assistant Fellowship in Emergency Medicine Jennifer S. Foster PA-C Dina Mantis PA-C Acute Abdomen – causes Acute appendicitis Acute mesenteric ischemia/ischemic colitis Perforated bowel, acute peptic ulcer or tumor Spectrum of cholecystitis Asymptomatic gallstones Biliary colic Acute Cholecystitis Choledocholithiasis Cholangitis Pancreatitis Hemoperitoneum – perforated AAA, trauma, surgery Abcess Bariatric surgery complications Acute abdomen Worry about abdominal pain in elderly, children, HIV infection, immune suppressed from steroids or chemotherapy History questions to ask: MerckManuals.com Where is the pain? What is the pain like? Have you had it before? Yes – recurrent problem such as ulcers, biliary colic, diverticulitis, mittelsherz No – think perforated ulcer, ectopic pregnancy, torsion How severe is pain? Pain out of proportion – mesenteric ischemia Does pain travel to other body parts? Right scapula – gallbladder pain Left shoulder – ruptured spleen, pancreatitis Other questions re abdominal pain: What relieves the pain? Sitting up right and leaning forward, think acute pancreatitis What other sx occur with the pain? a) vomiting before pain, then diarrhea = gastroenteritis b) delayed vomiting, no bowel movements, no gas = acute intestinal obstruction, SBO c) severe vomiting, then intense epigastric left chest or shoulder pain = perforation of esophagus Other historical questions the surgeon will want to know: Prior surgeries Surgical history, when – how recently, what, where, who did it? Also postop complications, postop course Pregnant or not Physical exam General, are they texting and talking and telling you pain is 10/10 or quiet, pale and diaphoretic? Ask patient where most tender area is, then start away from there, listen first, then percuss and palpate. -

Biomed Prep 12.Hwp

BIOMED PREP 12 Page 1 A 77ͲyearͲold man with a history of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, COPD, and a 90ͲpackͲyear smoking history presents to your clinic for acupuncture treatment. His temperature is 36.9°C (98.5°F), BP is 82/54 mm Hg, pulse is 125/min, and RR is 16/min. A pulsatile abdominal mass is palpable just superior to the umbilicus. There is diffuse abdominal tenderness, although rebound tenderness and guarding are absent. There is also slight skin discoloration noted in the left lower back. What is your next course of action? A. Needle PC6 + SP4 combination B. Needle Four Doors: RN12, ST25, RN6 C. Cupping therapy on local region D. Send the patient to emergency department Triad for Ruptured AAA ++ y This patient presents with the classic triad of symptoms for the diagnosis of a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA): abdominal pain, pulsatile abdominal mass, and hypotension. y In addition, this patient has several risk factors for an AAA rupture including HTN and COPD. y The skin discoloration along the left lower backy ma be due to a retroperitoneal hematoma that is associated with a ruptured AAA. A patient complains of abdominal pain with a pulsatile abdominal mass is palpable just superior to the umbilicus. What is the diagnosis? A. Thoracic aortic aneurysms B. Abdominal aneurysm C. Pancreatitis D. Bowel obstruction y The USPSTF recommends 1Ͳtime screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) with ______________ in men aged 65 to 75 years who have ever smoked. y Repair is indicated when the aneurysm becomes greater than ______ cm in diameter or grows more than 0.6 to 0.8 cm per year. -

Eponymous Signs in Dermatology

9/3/13 Eponymous signs in dermatology Indian Dermatol Online J. 2012 Sep-Dec; 3(3): 159–165. PMCID: PMC3505421 doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.101810 Eponymous signs in dermatology Bhushan Madke and Chitra Nayak Department of Skin and VD, Topiw ala National Medical College and BYL Charitable Hospital, Mumbai, India Address for correspondence: Prof. Chitra Nayak, Department of Skin and VD, OPD 14, Second floor, OPD building, Nair Hospital and T.N. Medical College, Dr. A.L Nair Road, Mumbai Central, Mumbai - 400 008, India. E-mail: [email protected] Copyright : © Indian Dermatology Online Journal This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, w hich permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original w ork is properly cited. Abstract Clinical signs reflect the sheer and close observatory quality of an astute physician. Many new dermatological signs both in clinical and diagnostic aspects of various dermatoses are being reported and no single book on dermatology literature gives a comprehensive list of these “signs” and postgraduate students in dermatology finds it difficult to have access to the description, as most of these resident doctor do not have access to the said journal articles. “Signs” commonly found in dermatologic literature with a brief discussion and explanation is reviewed in this paper. Keywords: Signs, dermatology, clinical, histology INTRODUCTION Eyes see what the mind knows The word “sign” refers to important physical finding or observation made by the physician when examining the patient. Dermatologic diagnosis relies on the careful observation and documentation of signs, which can be highly pathognomonic for a certain conditions. -

Essential Orthopedic Review Questions and Answers for Senior Medical Students

Adam E. M. Eltorai Craig P. Eberson Alan H. Daniels Editors Essential Orthopedic Review Questions and Answers for Senior Medical Students 123 Essential Orthopedic Review Adam E. M. Eltorai • Craig P. Eberson Alan H. Daniels Editors Essential Orthopedic Review Questions and Answers for Senior Medical Students Editors Adam E. M. Eltorai Craig P. Eberson Warren Alpert Medical School Department of Orthopedic Brown University Surgery Providence, RI Warren Alpert Medical School USA Brown University Providence, RI Alan H. Daniels USA Department of Orthopedic Surgery Warren Alpert Medical School Brown University Providence, RI USA ISBN 978-3-319-78386-4 ISBN 978-3-319-78387-1 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78387-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018943261 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of transla- tion, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimi- lar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of pub- lication. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-60924-2 - Case Studies in Pediatric Emergency and Critical Care Ultrasound Edited by David J. Mclario and John L. Kendall Index More information Index abdominal distension, 215 breath-stacking, 192, 194 abdominal pain, 117, 121, 129, 147, 158, 159, 195 bronchiolitis, 100 abscess, 90, 91, 182, 183, 184, 254, 276 ultrasound evaluation, 102 diagnosis, 182 ultrasound technique, 101, 102 drainage, 90–97, 254, 256, 276 bupivacaine, 227 incision, 255 localization, 254 cardiac arrest, 62 peri-orbital, 88 cardiac tamponade, 43, 47 peri-tonsillar (PTA), 94, 95, 97 cardiovascular assessment, 38 subperiosteal, 85, 86, 88 neonate, 57 tubo-ovarian (TOA), 156, 157 RUSH protocol, 43–47 ultrasound appearance, 92 carotid artery, 95, 96 uncooperative patient, 275 carpal tunnel, 244 Achilles tendon rupture, 177, 178 cat scratch disease (CSD), 91 acoustic shadowing, 4, 7 cellulitis, 182, 184, 276 acute lymphocytic leukemia, 62 cutaneous, 90 adjunctive measures, 278, 279, 280 diagnosis, 182 Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) primary survey, orbital, 87, 88 36 peritonsillar, 94, 95, 97 air bronchogram, 106, 107 preseptal, 87, 88 air bubble artifact, 277 central venous pressure airway assessment, 36 assessment, 38 A-lines, 5, 100, 101 RUSH protocol, 47 anesthetic infiltration, 255 cervical lymphadenitis, 90 anisotropy, 179 cervical sign, 127 ankle pain, 177 chest trauma, 25, 26, 32 antecubital fossa, 202 chest x-ray, 110 anterior fontanel, 66, 67 child abuse, neonate, 58 apnea, 64 cholecystitis, 3, 130, 132 appendicitis, 118, -

Color Index: Notes , Important , Extra , Davidson’S Editing File Feedback

Objectives: ● Define acute abdomen. ● Describe a general approach to acute abdomen. ● Discuss common causes of acute abdomen through case scenarios. Resources: ● Davidson’s (Chapter 12 pg 159). ● 436 doctors slides. ● 435’s teamwork. ● Surgical Recall. Done by: Nada Alsomali, Rawan Alqahtani, Ruba Barnawi Leaders: Heba Alnasser, Jawaher Abanumy, Mohammed Habib, Mohammad Al-Mutlaq Revised by: Maha AlGhamdi Color index: Notes , Important , Extra , Davidson’s Editing file Feedback Acute Abdomen Definition: Acute abdomen denotes any sudden, spontaneous (not influenced by something else), non-traumatic disorder in the abdominal area that requires urgent surgery in most cases (not all acute abdomens are managed surgically, some are medical ex: pancreatitis, also bowel obstruction can be treated conservatively 50% of the time). Full list of possible causes of acute abdominal pain (extra from the book) Pathophysiology: Visceral Pain Somatic (parietal) Pain ● Visceral pain is insensitive to mechanical, thermal, ● The parietal peritoneum is sensitive to mechanical, or chemical stimulation, therefore can be handled, thermal or chemical stimulation, so when irritated, a 1 cut or cauterized painlessly. reflex contraction of muscles, causing guarding 2 ● However, they are sensitive to tension (whether and hyperaesthesia of skin. due to overdistension or traction), visceral muscle ● Somatic pain is classically described as sharp,and is spasm and ischaemia. usually well localized. ● Visceral pain -

P Age 17 ISSN: 2456

ISSN: 2456 - 530X EIJO: Journal of Ayurveda, Herbal Medicine and Innovative Research (EIJO - AHMIR) Einstein International Journal Organization (EIJO) Available Online at: www.eijo.in Volume – 2, Issue – 2, March - April - 2017, Page No. : 17 - 22 Review on Appendix and its management Dr. Dinesh Kumar, BAMS, PG Scholar (Shalya Tantra), BHU, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh. Dr M.Sahu (Guide), BAMS, MS (Shalya Tantra), Dean BHU, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh. Abstract The diagnosis of acute appendicitis is predominantly a clinical one; many patients present with a typical history and examination findings. The cause of acute appendicitis is unknown but is probably multifactorial; luminal obstruction and dietary and familial factors have all been suggested. Appendicectomy is the treatment of choice and is increasingly done as a laparoscopic procedure. This article reviews the presentation, investigation, treatment, and complications of acute appendicitis and appendicectomy. Keywords: Appendix, Pain, Pathology, Inflamed, Laparoscopic. 1. Introduction Appendicitis is inflammation of the appendix. Symptoms commonly include right lower abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and decreased appetite. However, approximately 40% of people do not have these typical symptoms. Severe complications of a ruptured appendix include widespread, painful inflammation of the inner lining of the abdominal wall and sepsis. Appendicitis is caused by a blockage of the hollow portion of the appendix. This is most commonly due to a calcified "stone" made of feces. Inflamed lymphoid tissue from a viral infection, parasites, gallstone, or tumors may also cause the blockage. This blockage leads to increased pressures in the appendix, decreased blood flow to the tissues of the appendix, and bacterial growth inside the appendix causing inflammation. -

Systemic Manifestations and Opportunistic Infections in Paediatric Hiv

Atlas of Paediatric HIV Infection PART II: SYSTEMIC MANIFESTATIONS AND OPPORTUNISTIC INFECTIONS IN PAEDIATRIC HIV Regina Oladokun, Ombeva Malande, Brian Eley Introduction Symptoms and signs of HIV infection in childhood similar to those of other diseases seen in the tropics; but may be more severe and occur more frequently and more commonly infectious in nature. Early features are usually non-specific: - Fever - Diarrhoea - Failure to thrive - Cough - Generalized lymphadenopathy Later the child presents with features indicative of severe immune suppression: - Signs of opportunistic infections e.g. tuberculosis - Recurrent and more severe forms of common illnesses e.g. bacterial pneumonia - Malignancies e.g. Kaposi sarcoma HIV is also systemic and all parts of the body can be affected by the virus itself. Systemic manifestations of HIV infection include: - Skin and oral mucosa (Part 1 of the atlas) - Malnutrition - Reticuloendothelial system- generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly - Blood - anaemia, thrombocytopaenia and leukopenia - Lung - lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis - Central nervous system – encephalopathy - Renal – nephropathy - Cardiovascular - cardiomyopathy. This second part of the atlas deals with non-dermatological manifestations of paediatric HIV infection including opportunistic infections, malignancies, systemic manifestations of the disease and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome that may complicate antiretroviral therapy. http://openbooks.uct.ac.za/hivatlas 134 Atlas of Paediatric HIV Infection CHAPTER 9: PAROTID ENLARGEMENT Parotid enlargement is estimated to occur in about 3 to 6% of HIV positive adults and 1 to 10% of children and is so unusual in the HIV negative population that cystic enlargement of the parotid gland is an indication for HIV testing. It is secondary to benign lymphoepithelial cysts and is categorised under stage 2 HIV disease.