Framing the Vote for Brexit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Decarbonising Aid: Why We Must Stop UK Financing for Fossil Fuels Overseas Table 1: CDC’S Direct Investments in Fossil Fuel Infrastructure

Campaign briefing Decarbonising aid Why we must stop UK financing for fossil fuels overseas May 2020 Photo: decoalonize.org CC: BY-NC-SA 2.0 Environmental activists in Kenya are determined to show that coal has no place in the country’s energy future. Why aid for fossil fuels must end • These investments are only one part of UK public financing for fossil fuels overseas which undermine • The world has ten years to decarbonise the global the government’s national commitments on economy and limit global temperature rises to emissions reductions. Since the Paris Agreement O 1.5 C – the target set by the Paris Agreement in was signed, approximately £568 million of UK aid 2015. This is an absolutely crucial demand for has been invested in fossil fuel projects overseas. frontline communities whose lands and livelihoods If we include export credits provided by UK Export will be destroyed by climate breakdown. Finance (UKEF) for fossil fuels, that number rises to • The UK government argues that investing in oil and £3.9 billion. gas is a good medium-term alternative to coal • Despite claims to be supporting a transition to power for countries in the global south. However, cleaner energy, CDC has £213 million of active this argument has been thoroughly debunked as investments in projects using the most polluting it will create fossil fuel dependency and lock in fuels, including diesel and heavy fuel oil.2 In 1 high carbon emissions for generations to come. countries including Ghana, CDC’s projects are also • UK aid is legally required to be spent on poverty contributing to the privatisation of energy systems, reduction. -

FCO Annual Report & Accounts 2016

Annual Report & Accounts: 2016 - 2017 Foreign & Commonwealth Office Annual Report and Accounts 2016–17 (For the year ended 31 March 2017) Accounts presented to the House of Commons pursuant to Section 6(4) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 Annual Report presented to the House of Commons by Command of Her Majesty Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 6 July 2017 HC 15 © Crown copyright 2017 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/ doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Finance Directorate, King Charles Street, London, SW1A 2AH Print ISBN 9781474142991 Web ISBN 9781474143004 ID P002873310 07/17 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Designed in-house by the FCO Communication Directorate Foreign & Commonwealth Office Annual Report and Accounts 2016 - 2017 - Contents Contents Foreword by the Foreign Secretary ......................................................................................... 1 Executive -

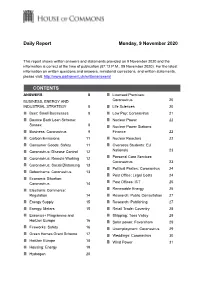

Daily Report Monday, 9 November 2020 CONTENTS

Daily Report Monday, 9 November 2020 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 9 November 2020 and the information is correct at the time of publication (07:12 P.M., 09 November 2020). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 8 Licensed Premises: BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Coronavirus 20 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 8 Life Sciences 20 Beer: Small Businesses 8 Low Pay: Coronavirus 21 Bounce Back Loan Scheme: Nuclear Power 22 Sussex 8 Nuclear Power Stations: Business: Coronavirus 9 Finance 22 Carbon Emissions 11 Nuclear Reactors 22 Consumer Goods: Safety 11 Overseas Students: EU Coronavirus: Disease Control 12 Nationals 23 Coronavirus: Remote Working 12 Personal Care Services: Coronavirus 23 Coronavirus: Social Distancing 13 Political Parties: Coronavirus 24 Debenhams: Coronavirus 13 Post Office: Legal Costs 24 Economic Situation: Coronavirus 14 Post Offices: ICT 25 Electronic Commerce: Renewable Energy 25 Regulation 14 Research: Public Consultation 27 Energy Supply 15 Research: Publishing 27 Energy: Meters 15 Retail Trade: Coventry 28 Erasmus+ Programme and Shipping: Tees Valley 28 Horizon Europe 16 Solar power: Faversham 29 Fireworks: Safety 16 Unemployment: Coronavirus 29 Green Homes Grant Scheme 17 Weddings: Coronavirus 30 Horizon Europe 18 Wind Power 31 Housing: Energy 19 Hydrogen 20 CABINET OFFICE 31 Musicians: Coronavirus 44 Ballot Papers: Visual Skateboarding: Coronavirus 44 Impairment 31 -

Her Majesty's Government and Her Official Opposition

Her Majesty’s Government and Her Official Opposition The Prime Minister and Leader of Her Majesty’s Official Opposition Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP || Leader of the Labour Party Jeremy Corbyn MP Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury (Chief Whip). He will attend Cabinet Rt Hon Mark Spencer MP remains || Nicholas Brown MP Treasurer of HM Household (Deputy Chief Whip) Stuart Andrew MP appointed Vice Chamberlain of HM Household (Government Whip) Marcus Jones MP appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP appointed || John McDonnell MP Chief Secretary to the Treasury - Cabinet Attendee Rt Hon Stephen Barclay appointed || Peter Dowd MP Exchequer Secretary to the Treasury Kemi Badenoch MP appointed Paymaster General in the Cabinet Office Rt Hon Penny Mordaunt MP appointed Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, and Minister for the Cabinet Office Rt Hon Michael Gove MP remains Minister of State in the Cabinet Office Chloe Smith MP appointed || Christian Matheson MP Secretary of State for the Home Department Rt Hon Priti Patel MP remains || Diane Abbott MP Minister of State in the Home Office Rt Hon James Brokenshire MP appointed Minister of State in the Home Office Kit Malthouse MP remains Parliamentary Under Secretary of State in the Home Office Chris Philp MP appointed Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, and First Secretary of State Rt Hon Dominic Raab MP remains || Emily Thornberry MP Minister of State in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office Rt Hon James Cleverly MP appointed Minister of State in the Foreign -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

House of Commons Official Report Parliamentary

Thursday Volume 664 26 September 2019 No. 343 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 26 September 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 843 26 SEPTEMBER 2019 Speaker’s Statement 844 there will be an urgent question later today on the House of Commons matter to which I have just referred, and that will be an opportunity for colleagues to say what they think. This is something of concern across the House. It is Thursday 26 September 2019 not a party political matter and, certainly as far as I am concerned, it should not be in any way, at any time, to any degree a matter for partisan point scoring. It is The House met at half-past Nine o’clock about something bigger than an individual, an individual party or an individual political or ideological viewpoint. Let us treat of it on that basis. In the meantime, may I just ask colleagues—that is all I am doing and all I can PRAYERS do as your representative in the Chair—please to lower the decibel level and to try to treat each other as opponents, not as enemies? [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Sir Peter Bottomley (Worthing West) (Con): On a point of order, Mr Speaker. Speaker’s Statement Mr Speaker: Order. I genuinely am not convinced, but I will take one point of order if the hon. Gentleman Mr Speaker: Before we get under way with today’s insists. -

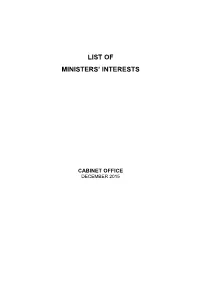

List of Ministers' Interests

LIST OF MINISTERS’ INTERESTS CABINET OFFICE DECEMBER 2015 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Prime Minister 3 Attorney General’s Office 5 Department for Business, Innovation and Skills 6 Cabinet Office 8 Department for Communities and Local Government 10 Department for Culture, Media and Sport 12 Ministry of Defence 14 Department for Education 16 Department of Energy and Climate Change 18 Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs 19 Foreign and Commonwealth Office 20 Department of Health 22 Home Office 24 Department for International Development 26 Ministry of Justice 27 Northern Ireland Office 30 Office of the Advocate General for Scotland 31 Office of the Leader of the House of Commons 32 Office of the Leader of the House of Lords 33 Scotland Office 34 Department for Transport 35 HM Treasury 37 Wales Office 39 Department for Work and Pensions 40 Government Whips – Commons 42 Government Whips – Lords 46 INTRODUCTION Ministerial Code Under the terms of the Ministerial Code, Ministers must ensure that no conflict arises, or could reasonably be perceived to arise, between their Ministerial position and their private interests, financial or otherwise. On appointment to each new office, Ministers must provide their Permanent Secretary with a list in writing of all relevant interests known to them which might be thought to give rise to a conflict. Individual declarations, and a note of any action taken in respect of individual interests, are then passed to the Cabinet Office Propriety and Ethics team and the Independent Adviser on Ministers’ Interests to confirm they are content with the action taken or to provide further advice as appropriate. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Tuesday Volume 687 19 January 2021 No. 162 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 19 January 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 753 19 JANUARY 2021 754 Chris Law (Dundee West) (SNP) [V]: Global poverty House of Commons has risen for the first time in more than 20 years, and by the end of this year, it is estimated that there will be Tuesday 19 January 2021 more than 150 million people in extreme poverty.Against that backdrop, the UK Government recklessly abolished the Department for International Development, they The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock are reneging on their 0.7% of GNI commitment, and they do not even mention eradicating poverty in the seven global challenges that UK aid is to be focused on. PRAYERS Can the Minister explicitly commit to eradicating poverty within the new official development assistance framework, rather than pursuing inhumane and devastating cuts as [MR SPEAKER ] in the Chair part of the Prime Minister’s little Britain vanity project? Virtual participation in proceedings continued (Order, 4 June and 30 December 2020). James Duddridge: The hon. Gentleman knows that [NB: [V] denotes a Member participating virtually.] we share a passion for international development. These specific targets do aim to alleviate and eradicate poverty, but the causes of poverty and the solutions to it are complex. That is why the merger of the Departments Oral Answers to Questions works, dealing with development and diplomacy alongside one another to overcome the scourge of poverty, which, sadly, has increased not decreased as a result of covid. -

Ministerial Departments CABINET OFFICE March 2021

LIST OF MINISTERIAL RESPONSIBILITIES Including Executive Agencies and Non- Ministerial Departments CABINET OFFICE March 2021 LIST OF MINISTERIAL RESPONSIBILITIES INCLUDING EXECUTIVE AGENCIES AND NON-MINISTERIAL DEPARTMENTS CONTENTS Page Part I List of Cabinet Ministers 2-3 Part II Alphabetical List of Ministers 4-7 Part III Ministerial Departments and Responsibilities 8-70 Part IV Executive Agencies 71-82 Part V Non-Ministerial Departments 83-90 Part VI Government Whips in the House of Commons and House of Lords 91 Part VII Government Spokespersons in the House of Lords 92-93 Part VIII Index 94-96 Information contained in this document can also be found on Ministers’ pages on GOV.UK and: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/government-ministers-and-responsibilities 1 I - LIST OF CABINET MINISTERS The Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP Prime Minister; First Lord of the Treasury; Minister for the Civil Service and Minister for the Union The Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP Chancellor of the Exchequer The Rt Hon Dominic Raab MP Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs; First Secretary of State The Rt Hon Priti Patel MP Secretary of State for the Home Department The Rt Hon Michael Gove MP Minister for the Cabinet Office; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster The Rt Hon Robert Buckland QC MP Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice The Rt Hon Ben Wallace MP Secretary of State for Defence The Rt Hon Matt Hancock MP Secretary of State for Health and Social Care The Rt Hon Alok Sharma MP COP26 President Designate The Rt Hon -

The Tigray War & Regional Implications

THE TIGRAY WAR & REGIONAL IMPLICATIONS (VOLUME 1) November 2020 to June 2021 1 CONTENTS 1. Foreword …………………………………………………………………………… 4 2. Introduction: war, offensives and atrocities 2.1 Overview …………………………………………………………………………… 7 2.2 Early attempts to halt the fighting ……………………………………………… 10 2.3 The war escalates …………………………………………………………………. 13 3. Ethiopia at war 3.1 The Federal Government v Tigray Regional State ……………………………. 16 3.2 Prime Minister Abiy’s short-lived whirlwind of reform ……………………... 30 3.3 An inexorable drive towards conflict 2018 – 2020 …………………………….. 49 3.4 President Isaias and Prime Minister Abiy – who is in the driving seat? ……. 60 4. Progress of the war 4.1 ENDF offensives along the southwestern front ……………………………….. 73 4.2 The northern fronts ………………………………………………………………. 76 4.3 The Southern Front ………………………………………………………………. 78 4.4 The ENDF’s strategy ……………………………………………………………... 78 4.5 Retreat and consolidation ……………………………………………………….. 80 4.6 TDF expansion and the start of semi-conventional warfare …………………. 82 4.7 Overall War Progress: November 2020 to May 2021 …………………………. 84 4.8 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………… 88 5. The Ethiopian national context 5.1 Contextualising the war in Tigray ……………………………………………… 91 5.2 A threat to Ethiopia’s integrity? ………………………………………………… 92 5.3 Conflict and the rule of law ……………………………………………………... 94 5.4 Oromia politics and conflict - optimism and excitement ……………………. 95 5.5 Amhara politics and conflict …………………………………………………… 102 5.6 The south, east and west ……………………………………………………….. 112 5.7 Somali Region …………………………………………………………………… 113 5.8 Afar Region ……………………………………………………………………… 115 5.9 Benishangul Gumuz ……………………………………………………………. 116 5.10 Socio-economic stakes and the cost of the war ………………………………. 117 5.11 Concluding remarks ……………………………………………………………. 119 6. Diplomatic Efforts 6.1 UN Security Council and the African Union ………………………………… 122 6.2 The United States of America …………………………………………………. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Monday Volume 613 11 July 2016 No. 23 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 11 July 2016 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2016 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON.DAVID CAMERON, MP, MAY 2015) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. David Cameron, MP FIRST SECRETARY OF STATE AND CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. George Osborne, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Michael Fallon, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. Michael Gove, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,INNOVATION AND SKILLS AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Sajid Javid, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Stephen Crabb, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH—The Rt Hon. Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION AND MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES—The Rt Hon. Nicky Morgan, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT—The Rt Hon. Justine Greening, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENERGY AND CLIMATE CHANGE—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR TRANSPORT—The Rt Hon. -

Boris's Government

BORIS’S GOVERNMENT CABINET Lord True, minister of state DEPARTMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION SCOTLAND OFFICE Rishi Sunak, chancellor of the exchequer Penny Mordaunt, paymaster general Elizabeth Truss, secretary of state for international trade; Gavin Williamson, secretary of state for education Alister Jack, secretary of state for Scotland Dominic Raab, first secretary of state, secretary of state for Chloe Smith, minister of state for the constitution and resident of the Board of Trade; minister for women Michelle Donelan, minister of state Douglas Ross, parliamentary under-secretary of state foreign and commonwealth affairs devolution and equalities Nick Gibb, minister of state for school standards Priti Patel, secretary of state for the home department Lord Agnew of Oulton, minister of state Conor Burns, minister of state Baroness Berridge, parliamentary under-secretary of state WALES OFFICE Michael Gove, chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster; minister Jacob Rees-Mogg, leader of the House of Commons; lord Greg Hands, minister of state Vicky Ford, parliamentary under-secretary of state Simon Hart, secretary of state for Wales for the Cabinet Office president of the council Graham Stuart, parliamentary under-secretary of state Gillian Keegan, parliamentary under-secretary of state David TC Davies, parliamentary under-secretary of state Ben Wallace, secretary of state for defence Baroness Evans of Bowes Park, leader of the House of Lords (minister for investment) Matt Hancock, secretary of state for health and social