V-Boats Off Natal the Local Ocean War, 1942-1944

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wolf Pack the Wolf Pack: a Collection of U-Boat Modelling

The Wolf Pack The Wolf Pack: A Collection Of U-Boat Modelling Articles Page 1 The Wolf Pack Contents Introduction Articles: Kriegsmarine U-Boat Colours & Markings Type VIIC Free-Flooding Vent Patterns Type VII U-Boat Modifications The Snorting Bull Insignia U 96 & The Laughing Sawfish German U-Boat Victory Pennants U-Boat Model Kits & Accessories Super-detailing Revell’s 1/72nd Type VIIC U-Boat* Revell Type VIIC Checklist Appendices: References Photo Sources Recommended Reading Index *Super-detailing Revell’s 1/72nd Type VIIC U-Boat by Wink Grisé All other articles by Dougie Martindale All text and drawings copyright © Dougie Martindale / Wink Grisé / Accurate Model Parts, 2010 The Wolf Pack: A Collection Of U-Boat Modelling Articles Page 2 The Wolf Pack Contents Introduction ............................................................................................. 7 Induction ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 A seminal release .......................................................................................................................................... 8 The allure of the VIIC .................................................................................................................................. 9 A growing collection ..................................................................................................................................... 9 The Wolf Pack ........................................................................................................................................... -

A Kriegsmarine U VII. Osztályú Tengeralattjárói

Haditechnika-történet Kelecsényi István* – Sárhidai Gyula** Akik majdnem megnyerték az Atlanti csatát – A Kriegsmarine U VII. osztályú tengeralattjárói I. rész 1. ábra. VII. osztályú U-boot bevetésre indul a kikötőből (Festmény) AZ előzmények főleg kereskedelmi hajót süllyesztettek el 199 darabos veszteség ellenében. A német búvárnaszádok a háború Az első világháború után a békefeltételek nem engedték során komoly problémát okoztak az antant hatalmaknak a meg Németországnak a tengeralattjárók hadrendben tartá- nyersanyag utánpótlásában és élelmiszerszállítások bizto- sát. Ennek oka, hogy a Nagy Háborúban több mint 5000, sításában. ÖSSZEFOGLALÁS: A németek közepes méretű tengeralattjáró típusa a VII. ABSTRACT: The Class VII U-boats were the German medium-size submarine osztály volt. A német haditengerészet legnagyobb ászai – Günther Prien type. The greatest aces of the German Navy – Corvette captain Günther Prien, korvettkapitány, Otto Kretschmer fregattkapitány és Joachim Schepke fre- Frigate captain Otto Kretschmer and Frigate captain Joachim Schepke – gattkapitány – ezeken a hajókon szolgáltak. A VII. osztály változatai elsősor- served on these boats. Variants of the Class VII fought mainly in the Atlantic ban az Atlanti-óceánon, a brit utánpótlási vonalak fő hadszínterén harcoltak, Ocean, on the main battlefield of the British supply lines, and between 1941 és 1941 és 1943 között majdnem sikerült kiéheztetniük és térdre kényszerí- and 1943 they almost starved and brought to heels the Great Britain. The teniük Nagy-Britanniát. A németek -

March 2010 Phoenix, Arizona Volume 16 - Issue 3

The Monthly Newsletter of Perch Base - USSVI March 2010 Phoenix, Arizona Volume 16 - Issue 3 http://www.perch-base.org What’s “Below Decks” in the MidWatch ITEM Page # Booster club and Float 2 support members Base Officers and Sailing 3 Orders Our Generous Sponsors 4 What a Great Way to Earn 5 Money From The Wardroom 6 February Meeting 6 Minutes Chaplain’s Column 9 Shipmate-to-Shipmate 10 Lest We Forget Those Still On Patrol Women on Submarines MARCH ETERNAL PATROLS Kap(SS) 4 Kid(SS) 11 Cold War “Did You Know” 12 USS PERCH (SS-176) 03 Mar 1942 6 POWs Perch Base Birthdays 13 Scuttled after Japanese Depth Charge Attack Lost Boat - USS Tullibee 14 USS GRAMPUS (SS-207) 05 Mar 1943 71 Lost (SS-284) Japanese Surface Attack, Solomon Islands “Digging Deep” 16 USS H1 (SS-28) 12 Mar 1920 4 Lost The Submarine in History 17 “World War II to 2000” Foundered off Santa Margarita Island, CA Mailing Page 31 USS TRITON (SS-201) 15 Mar 1943 74 Lost Japanese Surface Attack off New Guinea USS KETE (SS-369) 20 Mar 1943 87 Lost Unknown causes between Okinawa and Midway ! Ines USS F4 (SS-23) 21 Mar 1915 21 Lost appened Battery Explosion off Honolulu ’s H submar It In year USS TRIGGER (SS-237) 26 Mar 1945 89 Lost a n Japanese Air/Surface Attack in East China Sea omenthi W wi -- 9 USS TULLIBEE (SS-284) 26 Mar 1944 79 Lost age p Circular run of own Torpedo off Palau Islands tory s NEXT MEETING 12 noon, Saturday, Mar. -

On Our Doorstep Parts 1 and 2

ON 0UR DOORSTEP I MEMORIAM THE SECOD WORLD WAR 1939 to 1945 HOW THOSE LIVIG I SOME OF THE PARISHES SOUTH OF COLCHESTER, WERE AFFECTED BY WORLD WAR 2 Compiled by E. J. Sparrow Page 1 of 156 ON 0UR DOORSTEP FOREWORD This is a sequel to the book “IF YOU SHED A TEAR” which dealt exclusively with the casualties in World War 1 from a dozen coastal villages on the orth Essex coast between the Colne and Blackwater. The villages involved are~: Abberton, Langenhoe, Fingringhoe, Rowhedge, Peldon: Little and Great Wigborough: Salcott: Tollesbury: Tolleshunt D’Arcy: Tolleshunt Knights and Tolleshunt Major This likewise is a community effort by the families, friends and neighbours of the Fallen so that they may be remembered. In this volume we cover men from the same villages in World War 2, who took up the challenge of this new threat .World War 2 was much closer to home. The German airfields were only 60 miles away and the villages were on the direct flight path to London. As a result our losses include a number of men, who did not serve in uniform but were at sea with the fishing fleet, or the Merchant avy. These men were lost with the vessels operating in what was known as “Bomb Alley” which also took a toll on the Royal avy’s patrol craft, who shepherded convoys up the east coast with its threats from: - mines, dive bombers, e- boats and destroyers. The book is broken into 4 sections dealing with: - The war at sea: the land warfare: the war in the air & on the Home Front THEY WILL OLY DIE IF THEY ARE FORGOTTE. -

U-Boot Im Focus 2007 – 2020

Inhaltsverzeichnis U-BOOT IM FOCUS 2007 – 2020 U-BOOT IM FOCUS – Herausgeber: Axel Urbanke, Luftfahrtverlag-Start 1 Edition Nr. 1 (2007) Seite Minenleger / minelayer UII U-219, 1942 Editorial 2 Typ VII A Boote / type VII a boats U-31, 1939 3 Typ II Boote / type II boats U-9, 1939 4 U-141 5 Typ VII A Boote / type VII a boats U-33, 1939 6 U-28, U-29, U-30, U-33, 1939 7 U-29, 1939 7 Typ VII B Boote / type VII b boats U-53, 1939 8 U-202 9 U-95, 1941 9 Typ VII C Boote / type VII c boats U-604, 1942 10 U-404, 1943 11 U-262, 1943 12 U-480, 1944 13 Typ IX Boote / type IX boats U-67 14 U-108, 1941 15 Elektroboote / Electroboats U-2360, 1945 16 U-3038, 1945 17 Türme / conning towers U-19 und U-20 — große Turmembleme aus der Anfangszeit des Krieges 18/19 U-40 — mit Totenkopf und Regenschirm 20/21 Farbfotos / colorpbotos U-177, Farbfotos von der 2. Feindfahrt 22/23 Boot im Focus / boat in focus U-652 — das Boot mit der seltenen Tupfentarnung 24-28 Dokumente / documents Eine Einladung der besonderen Art 29 Unbekannte Embleme / unknown emblems Die säugende Wölfin von U-339 30 Fotos mit Geschichte / pictures with a story Hilfskreuzer „Atlantis“ versenkt — U-Boote als Retter 31-37 Wimpel / pennant Zerstörerversenkung — dem Schicksal ins Auge geschaut 38-40 Porträt / portrait Kapitänleutnant Günther Krech 41-44 2 Ungewöhnliches / unusual Das „bunte“ Funkgerät von U-48 45 Szenerie / scenery „Milchkuh“ in Sicht! 46/47 Schicksale / fate Glückliche Heimkehr 48/UIII U-Tanker / U-Tanker U-460, 1943 UIII Edition Nr. -

The Axis and Allied Maritime Operations Around Southern Africa, 1939-1945

THE AXIS AND ALLIED MARITIME OPERATIONS AROUND SOUTHERN AFRICA, 1939-1945 Evert Philippus Kleynhans Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Military Science (Military History) in the Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof I.J. van der Waag Co-supervisor: Dr E.K. Fedorowich December 2018 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: December 2018 Copyright © 2018 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract The majority of academic and popular studies on the South African participation in the Second World War historically focus on the military operations of the Union Defence Force in East Africa, North Africa, Madagascar and Italy. Recently, there has been a renewed drive to study the South African participation from a more general war and society approach. The South African home front during the war, and in particular the Axis and Allied maritime war waged off the southern African coast, has, however, received scant historical attention from professional and amateur historians alike. The historical interrelated aspects of maritime insecurity evident in southern Africa during the war are largely cast aside by contemporary academics engaging with issues of maritime strategy and insecurity in southern Africa. -

Master Thesis Project Front Page for the Master's Thesis

The Faculty of Humanities Master Thesis Project Front page for the Master’s thesis Submission June: [2019] Supervisor: Thijs J. Maarleveld Department: History Title, Danish: Tyske ubåde fra 2. Verdenskrig i danske farvande Title, English: German World War II Submarines in Danish Waters Min./Max. number of characters: 144,000 – 192,000 Number of characters in assignment1: 179.040 (60 – 80 normal pages) (1 norm page = 2400 characters incl. blanc spaces) Please notice in case your Master’s thesis project does not meet the minimum/maximum requirements stipulated in the curriculum your assignment will be dismissed and you will have used up one examination attempt. Solemn declaration I hereby declare that I have drawn up the assignment single-handed and independently. All quotes are marked as such and duly referenced. The full assignment or parts thereof have not been handed in as full or partial fulfilment of examination requirements in any other courses. Read more here: http://www.sdu.dk/en/Information_til/Studerende_ved_SDU/Eksamen.aspx Handed in by: First name: Last name: Date of birth Anders Jensen 20 /11 1975 1 Characters are counter from first character in the introduction until and including the last character in the conclusion. Footnotes are included. Charts are counted with theirs characters. The following is excluded from the total count: abstract, table of contents, bibliography, list of references, appendix. For more information, see the examination regulations of the course in the curriculum. 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements -

Osprey Publishing, Elms Court, Chapel Way, Botley, Oxford OX2 9LP, United Kingdom

WOLF PACK The Story of the U-Boat in World War II The Story - oat iq-Workd War 11 First published in Great Britain in 2005 by Osprey Publishing, Elms Court, Chapel Way, Botley, Oxford OX2 9LP, United Kingdom. Email: [email protected] Previously published as New Vanguard 51: Kriegsmarine U-boats 1939-45 (1); New Vanguard 55: Kriegsmarine U-boats 1939-45 (2); and Warrior 36: Grey Wolf. © 2005 Osprey Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Enquiries should be addressed to the Publishers. CIP data for this publication is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 84176 872 3 Editors: Anita Hitchings and Ruth Sheppard Design: Ken Vail Graphic Design, Cambridge, UK Artwork by Ian Palmer and Darko Pavlovic Index by Alan Thatcher Originated by The Electronic Page Company, Cwmbran, UK Printed and bound by L-Rex Printing Company Ltd 05 06 07 08 09 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 FOR A CATALOGUE OF ALL BOOKS PUBLISHED BY OSPREY PLEASE CONTACT: NORTH AMERICA Osprey Direct, 2427 Bond Street, University Park, IL 60466, USA E-mail: [email protected] ALL OTHER REGIONS Osprey Direct UK, P.O. Box 140, Wellingborough, Northants, NN8 2FA, UK E-mail: [email protected] www.ospreypublishing.com EDITOR'S NOTE All photographs, unless indicated otherwise, are courtesy of the U-Boot Archiv. -

Biber, Molch and Seehund WWII Kriegsmarine Submarine Boats 15Mm Coastal Warfare Releases Review by Rob Morgan

Biber, Molch and Seehund WWII Kriegsmarine submarine boats 15mm Coastal Warfare releases Review by Rob Morgan These releases from MY Miniatures add significantly to the 15mm naval and “special forces” models currently around in this scale. Each is a simple semi- submerged model, the “con” as Americans might say, on a small sea base, and with a range of potential options. Added to a pack of the 15mm MY Frogmen or with larger scale coastal forces boats, landing craft, etc., they will “beef up” a late- war NW Europe scenario, or a solo Mediterranean raid. They (allegedly) had some slight capacity for mine-laying too, which offers a different option to attacking a larger warship. They are 15mm scale, but of course, will easily fit into a 20mm or 25mm scenario, if used against say Airfix Landing Craft or MTB’s. Biber This is pack GERM 7, priced at around £2 for two. The model of the German mini-sub is 35mm long and 15mm wide. The control tower, with hatch, periscope, exhaust pipe and vision block detail pokes 15mm above the surface of the water. Detail is accurate, though minimal in a model which necessarily shows little beyond the “con.” It's easily painted, and if desired, by filing the hatch flat and replacing it with an “open” version, a pilot half-figure can be slipped into place for variation in a group of Bibers. Interestingly, the Biber (Beaver) was remarkably similar to the Molch' (Salamander), differing mainly in the fact that the pilot structure was placed centrally along the hull in the first, but well aft in the latter vessel. -

Long Night of the Tankers: Hitler's War Against Caribbean

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 Long Night of the Tankers: Hitler’s War Against Caribbean Oil Bercuson, David J.; Herwig, Holger H. University of Calgary Press Bercuson, D. J. & Herwig, H. H. "Long Night of the Tankers: Hitler’s War Against Caribbean Oil". Beyond Boundaries: Canadian Defence and Strategic Studies Series; 4. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/49998 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com LONG NIGHT OF THE TANKERS: HITLER’S WAR AGAINST CARIBBEAN OIL David J. Bercuson and Holger H. Herwig ISBN 978-1-55238-760-3 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

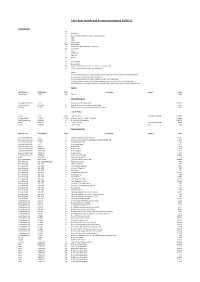

S & U Boat Models and Accessories Updated 29/06/15

S & U Boat models and Accessories Updated 29/06/15 1/72nd scale Key A Aluminium B Brass, turned machined or cast, not photo etched C Cloth D Decal M White Metal MM Multi Media P Photo-Etch - Brass, Stainless, Copper, etc. PM Paint Mask R Resin S PolyStyrene V Vacform W Wood Dis Discontinued U Unobtainable NOS New Old Stock. Have seen for sale Less than 12 months ago TBA To Be Announced, be patient, not available yet! NOTES: Boris Nakropin (facebook & Google+) skyorange(ebay.de), SRS and SmallRivets are the same person. Oto Greza can be contacted via www.rcsubs.cz. Any accessories that do not have a supplier, contact the manufacturer. If there is no part number, either the manufacturer does not use any or it is not available yet. Several figures are in the General section, although titled a specific type they can work for other types. Type IIA Manufacturer Part Number Type Description Supplier Price Special Navy 72001 MM Type II A £59.99 Type IIA Accessories Accurate Model Parts 72-01 P Detail Set for SN Type II Uboat € 39.95 Hecker & Goros KSHG 235 M German Navy Crew for submarine IIA (3 figs) £7.50 Nautilus 72-507 W Replacement Deck for Special Navy Type IIA U-boat £20.94 Type VII Models Amati 1602 MM Type VII B U47 Wonderland Models £299.99 Combat Models 72-101 V+MM German Type VIIC U-boat + Detail set $62.00 Czech Master Kits ML80418 R U-boot Typ VII C waterline € 147.50 Revell RV05015 S Type VII C U552 Wonderland Models £47.99 Revell RV05045 S Type VII C/41 Dis NOS Type VII Accessories Manufacturer Part Number Type Description Supplier -

Fishery Statistics 2005

Official Statistics of Norway D 386 Fishery Statistics 2005 Statistisk sentralbyrå • Statistics Norway Oslo–Kongsvinger Official Statistics of Norway This series consists mainly of primary statistics, statistics from statistical accounting systems and results of special censuses and surveys. The series is intended to serve reference and documentation purposes. The presentation is basically in the form of tables, figures and necessary information about data, collection and processing methods, in addition to concepts and definitions. A short overview of the main results is also included The series also includes the publications Statistical Yearbook of Norway and Svalbard Statistics. © Statistics Norway, January 2008 Symbols in tables Symbol When using material from this publication, Category not applicable . Statistics Norway shall be quoted as the source. Data not available .. Data not yet available ... ISBN 978-82-537-7315-5 Printed version Not for publication : ISBN 978-82-537-7316-2 Electronic version Nil - ISSN 1890-5811 Printed version Less than 0,5 of unit employed 0 ISSN 1890-582X Electronic version Less than 0,05 of unit employed 0,0 Topic Provisional or preliminary figure * Break in the homogeneity of a vertical — 10.05 series Break in the homogeneity of a horzontal | series Print: Statistics Norway Decimal punctuation mark , Official Statistics of Norway Fishery Statistics 2005 Preface This publication presents a statistical survey of the fishing industry and comprises a sample of accessible statistics. From the sea fisheries the publication presents statistics of fishermen, fishing vessels, catches and economic results. This edition also contains landings in Norway from foreign vessels. It also includes statistics of fish processing industry, external trade of fish and an overview of the state of some important fish stocks.