UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANDEAN PREHISTORY – Online Course ANTH 396-003 (3 Credits

ANTH 396-003 1 Andean Prehistory Summer 2017 Syllabus ANDEAN PREHISTORY – Online Course ANTH 396-003 (3 credits) – Summer 2017 Meeting Place and Time: Robinson Hall A, Room A410, Tuesdays, 4:30 – 7:10 PM Instructor: Dr. Haagen Klaus Office: Robinson Hall B Room 437A E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: (703) 993-6568 Office Hours: T,R: 1:15- 3PM, or by appointment Web: http://soan.gmu.edu/people/hklaus - Required Textbook: Quilter, Jeffrey (2014). The Ancient Central Andes. Routledge: New York. - Other readings available on Blackboard as PDFs. COURSE OBJECTIVES AND CONTENTS This seminar offers an updated synthesis of the development, achievements, and the material, organizational and ideological features of pre-Hispanic cultures of the Andean region of western South America. Together, they constituted one of the most remarkable series of civilizations of the pre-industrial world. Secondary objectives involve: appreciation of (a) the potential and limitations of the singular Andean environment and how human inhabitants creatively coped with them, (b) economic and political dynamism in the ancient Andes (namely, the coast of Peru, the Cuzco highlands, and the Titicaca Basin), (c) the short and long-term impacts of the Spanish conquest and how they relate to modern-day western South America, and (d) factors and conditions that have affected the nature, priorities, and accomplishments of scientific Andean archaeology. The temporal coverage of the course span some 14,000 years of pre-Hispanic cultural developments, from the earliest hunter-gatherers to the Spanish conquest. The primary spatial coverage of the course roughly coincides with the western half (coast and highlands) of the modern nation of Peru – with special coverage and focus on the north coast of Peru. -

Bats and Their Symbolic Meaning in Moche Iconography

arts Article Inverted Worlds, Nocturnal States and Flying Mammals: Bats and Their Symbolic Meaning in Moche Iconography Aleksa K. Alaica Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto, 19 Ursula Franklin Street, Toronto, ON M5S 2S2, Canada; [email protected] Received: 1 August 2020; Accepted: 10 October 2020; Published: 21 October 2020 Abstract: Bats are depicted in various types of media in Central and South America. The Moche of northern Peru portrayed bats in many figurative ceramic vessels in association with themes of sacrifice, elite status and agricultural fertility. Osseous remains of bats in Moche ceremonial and domestic contexts are rare yet their various representations in visual media highlight Moche fascination with their corporeal form, behaviour and symbolic meaning. By exploring bat imagery in Moche iconography, I argue that the bat formed an important part of Moche categorical schemes of the non-human world. The bat symbolized death and renewal not only for the human body but also for agriculture, society and the cosmos. I contrast folk taxonomies and symbolic classification to interpret the relational role of various species of chiropterans to argue that the nocturnal behaviour of the bat and its symbolic association with the moon and the darkness of the underworld was not a negative sphere to be feared or rejected. Instead, like the representative priestesses of the Late Moche period, bats formed part of a visual repertoire to depict the cycles of destruction and renewal that permitted the cosmological continuation of life within North Coast Moche society. Keywords: bats; non-human animals; Moche; moon imagery; priestess; sacrifice; agriculture; fertility 1. -

10 Best Full Days PERU

10 Best Full Days PERU Land of Contrasts Day 1 Machu Picchu Day 2 Titicaca Lake Day 3 Highland of Chinchero Day 4 Arequipa Day 5 Colca Valley Day 6 Cusco & nearby ruins Day 7 Tambopata Research Center Day 8 Cordillera Blanca Day 9 Kingdoms of the Moche Day 10 Nasca Lines & Tablazo de Ica 1 MACHU PICCHU AGUAS CALIENTES - MACHU PICCHU - SACRED VALLEY / CUSCO Breakfast in the hotel and early morning transfer by bus to the majestic ruins of Machu Picchu be- fore the arrival of most tourists. The impressive Inca citadel is placed on the side of a mountain. Its Quechua name means “Old Mountain”, but it is also known as “the Lost City of the Incas” since it remained hidden from the West until dis- covered by Hiram Bingham in 1911. It was built in the fifteenth century, and is attributed to the Inca Pachacutec. The archeological complex is divided into two zones that are contained within approximately twenty hectares. On the sides of the mountain, you can see up to four meters high agricultural terraces. Several plazas and build- ings, the most important being the Temple of the Sun, the Intihuatana or solar clock and calendar, the Temple of the Three Windows, the Main Tem- ple and the Condor Sector, make up the urban sector. There is also an impressive monolith of carved stone, three meters high and seven meters wide at the base, named the Sacred Stone. In or- der to build Machu Picchu, the Incas had to use blocks of stone brought from long distances. -

© Cambridge University Press Cambridge

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85099-5 - The Atlantic World: Europeans, Africans, Indians and Their Shared History, 1400-1900 Thomas Benjamin Index More information Index Abenakis, 310 Muslims in, 24–25 independence of Brazil, Acadians, 243–245, 494 Niger Delta chiefdoms, 609–612 Acosta, Josede,´ 281, 286 33 inspiration of early Adams, Abigail, 534 plant domestication, 34 revolutions, 518 Adams, John, 435, 525, savanna state development, reasons for anti-slavery 539 25–28 actions in Caribbean, Address to the Congress of slaves, indigenous 587–589 Angostura, 606–607 agricultural, 33 revolutionary republicanism, Africa, 24–35 as infantrymen/archers, 517 agriculture, 24, 25 27 and slavery, 518, 613.See Akan kingdom, as laborers, 27–28 also American animal domestication, 34 slave trade, indigenous, 28, Revolution; arts, 30 33, 35 Enlightenment; French Berbers in, 25 Songhay (See Songhay) Revolution; Haitian Canary Islands chiefdom (See South Africa chiefdom, 34 Revolution; Spanish Canary Islands) Thirstland, 33–34 America revolutions colonization, 662 trade in, 25, 29 agriculture Dyula, 82 tribute systems, 33 expansion in 14th-century early descriptions of, 80–81 underpopulation, in Europe, 38–39 economic/political sub-Saharan, 35 in pre-contact Africa development in Wolof, 81, 82 irrigated, 24 sub-Saharan, 34–35 Yoruba kingdom, 30.Seealso rain-fed, 25 endemic disease, 28–29, 35 Angola, and Portugal; in pre-contact Americas, 19, equatorial Central Africa antislavery, and Africa; 21 state development, 33 gender relations, in chinapa, 17 European disease, 35 Africa; Portuguese plant domestication, 22 famine, 35 imperium, in Africa; slash-and-burn, 21 forest-savanna edge state slavery; slave trade; West Ahuitzotl, 12 development, 28–29 Africa Aimore,´ 156 Ghana empire, 27 African Trade Act, 487 Akan kingdom (Africa), hearth of civilization, 25 Africanus, Leo, 28, 75, 117, Alaska, pre-contact herding in, 25 331 sub-arctic/arctic, 21 hunting/gathering in, 33–34 Age of Reason. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

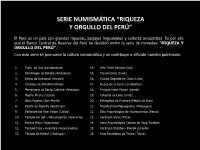

SERIE NUMISMÁTICA “RIQUEZA Y ORGULLO DEL PERÚ” El Perú es un país con grandes riquezas, paisajes inigualables y culturas ancestrales. Es por ello que el Banco Central de Reserva del Perú ha decidido emitir la serie de monedas: “RIQUEZA Y ORGULLO DEL PERÚ”. Con esta serie se promueve la cultura numismática y se contribuye a difundir nuestro patrimonio. 1. Tumi de Oro (Lambayeque) 14. Arte Textil Paracas (Ica) 2. Sarcófagos de Karajía (Amazonas) 15. Tunanmarca (Junín) 3. Estela de Raimondi (Ancash) 16. Ciudad Sagrada de Caral (Lima) 4. Chullpas de Sillustani (Puno) 17. Huaca de la Luna (La Libertad) 5. Monasterio de Santa Catalina (Arequipa) 18. Antiguo Hotel Palace (Loreto) 6. Machu Picchu (Cusco) 19. Catedral de Lima (Lima) 7. Gran Pajatén (San Martín) 20. Petroglifos de Pusharo (Madre de Dios) 8. Piedra de Saywite (Apurimac) 21. Arquitectura Moqueguana (Moquegua) 9. Fortaleza del Real Felipe (Callao) 22. Sitio Arqueológico de Huarautambo (Pasco) 10. Templo del Sol – Vilcashuamán (Ayacucho) 23. Cerámica Vicús (Piura) 11. Kuntur Wasi (Cajamarca) 24. Zona Arqueológica Cabeza de Vaca Tumbes) 12. Templo Inca - Huaytará (Huancavelica) 25. Cerámica Shipibo – Konibo (Ucayali) 13. Templo de Kotosh (Huánuco) 26. Arco Parabólico de Tacna (Tacna) 1 TUMI DE ORO Especificaciones Técnicas En el reverso se aprecia en el centro el Tumi de Oro, instrumento de hoja corta, semilunar y empuñadura escultórica con la figura de ÑAYLAMP ícono mitológico de la Cultura Lambayeque. Al lado izquierdo del Tumi, la marca de la Casa Nacional de Moneda sobre un diseño geométrico de líneas verticales. Al lado derecho del Tumi, la denominación en números, el nombre de la unidad monetaria sobre unas líneas ondulantes, debajo la frase TUMI DE ORO, S. -

Difusión De Reapertura De Museos Y Sitios Arqueológicos Mod

AMAZONAS Zona Arqueológica Monumental de Kuélap Abierto desde el 4 de marzo Dirección: Anexo Kuélap, Amazonas. Días de atención: De martes a domingo. Horario: De 8:00 a. m. a 2:00 p. m. Reserva: 939392347, [email protected]. Atencion de lunes a viernes de 9:00 a. m. a 4:00 p. m. Nota: El aforo máximo es de 360 personas por día, cada grupo estará conformado por un máximo de 8 personas más su guía u orientador local. AYACUCHO Museo de Sitio y Complejo Arqueológico Wari Abierto desde el 2 de marzo Dirección: Km. 23 Carretera Ayacucho-Quinua, Ayacucho. Días de atención: De martes a sábado Horario: De 9:00 a. m. a 4:00 p. m. Reserva: [email protected] Red social: https://www.facebook.com/DCC.Ayacucho AYACUCHO Complejo Arqueológico de Intihuatana Abierto desde el 2 de marzo Dirección: Distrito de Vischongo-Provincia de Vilcashuamán, Ayacucho. Días de atención: De martes a sábado Horario: De 9:00 a. m. a 4:00 p. m. Reserva: [email protected] Red social: https://www.facebook.com/DCC.Ayacucho CAJAMARCA Museo Arqueológico y Etnográfico del Conjunto Monumental Belén Abierto desde el 2 de marzo Dirección: Jr. Belén 631, Cajamarca. Días de atención: De martes a sábado Horario: De 9:30 a. m. a 2:30 p. m. Reserva: http://bit.ly/CMBelen Red social: https://www.facebook.com/DDCulturaCajamarca CAJAMARCA Sitio Arqueológico de Cumbe Mayo Abierto desde el 2 de marzo Dirección: Ubicado a 19 km. al suroeste de la ciudad de Cajamarca. Días de atención: De martes a sábado Horario: De 9:30 a. -

Moche Route – the Lost Kingdoms

MOCHE ROUTE – THE LOST KINGDOMS MAY 2019 MON 20 CIVILIZATIONS AT NORTHERN PERU: MOCHE AND CHIMU (L,D) 10:40 Airport pick up. 11:15 Visit to Site Museum at Huaca de la Luna, where you can admire a great collection of beatiful pottery and its iconography, created by Moche people. The tour continues to the archaeologycal area, a huge monument that exhibits colorful mural on decorated wall. This construction represents one of the most important and magnificient edifications of ancient Perú. 13:30 Seafood buffet at Huanchaco beach. 14:15 Vivential experience admiring typical fishing boats called “caballitos de totora”. Made of totora fiber, these ancient boats are still used every day by local fishermen. You can also experience a ride in one of these boats. 15:15 Visit to Chan Chan – Biggest mud city in the world, Cultural heritage of humanity. Built by Chimu inhabitants (700 dC – 1500 dC) is an impressive edification with very high walls, friezes and designs of great urban planification. 17:00 Hotel check in 20:00 Dinner TUE 21 THE AMAZING TREASURES OF THE LORD OF SIPAN (B, L) 06:15 Buffet breakfast 06:45 We´ll head to Magadalena de Cao, 70 kms. north of Trujillo, a few minutes from the shore, first stop to visit El Brujo complex. We´ll visit first the archaeolgycal zone, similar style to Huaca de la Luna, but different murals. We´ll continue to visit Cao Museum that shows the incredible and excellent preserved mummy of one of female governors of Moche culture, called Lady of Cao. -

Anthropology 433

Anthropology 433 ANDEAN ARCHAEOLOGY Spring 2018 Professor Clark L. Erickson PROFESSOR: Dr. Clark Erickson 435 Penn Museum [email protected] 215-898-2282 DESCRIPTION: ANTH 433: Andean Archaeology (Cross-listed as Latin American and Latino Studies 433) This course provides a basic survey of the prehistory of civilizations in the Central Andean Region of South America (the central highland and coastal areas that today are Peru and Bolivia and parts of Ecuador, Chile, and Argentina). Topics include the history of South American archaeology, peopling of the continent, origins and evolution of agriculture, early village life, ceremonial and domestic architecture, prehistoric art and symbolism, Andean cosmology and astronomy, indigenous technology, the historical ecology of landscapes, outside contacts and relationships, economics and trade, social and political structure, state formation and urbanism, and early contacts with Europeans. The lectures and readings are based on recent archaeological investigations and interpretations combined with appropriate analogy from ethnohistory and ethnography. The prehistory of the Amazonian lowlands and "the intermediate area" of northern South America will be covered in other courses. Slides and several films are used to illustrate concepts and sites presented in lecture. I generally do not stop the lecture to spell terminology, although periodically you will be provided handouts with lists of important terminology. Questions and comments are encouraged and may be asked before, during, or after lectures. I will also make use of artifacts from the extensive South American collections of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (Penn Museum).in class and/or in the collection rooms of the Penn Museum instead of in our regular classroom. -

Visitantes Del Museo De La Inquisición

ESTADÍSTICAS DE VISITANTES DE LOS MUSEOS Y SITIOS ARQUEOLÓGICOS DEL PERÚ (1992 - 2018) ÍI,� tq -- ESTADÍSTICAS DE VISITANTES DEL MUSEO DEL CONGRESO Y DE LA INQUISICIÓN Y DE LOS PRINCIPALES MUSEOS Y SITIOS ARQUEOLÓGICOS DEL PERÚ ÍNDICE Introducción P. 2 Historia del Museo Nacional del Perú P. 3 Estadísticas de visitantes del Museo del Congreso y de la Inquisición P. 19 Estadísticas de visitantes del Museo Nacional Afroperuano del P. 22 Congreso Estadísticas del Sitio Web del Museo del Congreso y de la Inquisición P. 23 Estadísticas de visitantes del Museo del Congreso y de la Inquisición P. 29 Estadísticas de visitantes del Palacio Legislativo P. 40 Estadísticas de visitantes de los principales museos y sitios P. 42 arqueológicos del Perú 1 INTRODUCCIÓN El Museo del Congreso tiene como misión investigar, conservar, exhibir y difundir la Historia del Congreso de la República y el Patrimonio Cultural a su cargo. Actualmente, según lo dispuesto por la Mesa Directiva del Congreso de la República, a través del Acuerdo de Mesa N° 139-2016-2017/MESA-CR, comprende dos museos: Museo del Congreso y de la Inquisición Fue establecido el 26 de julio de 1968. Está ubicado en la quinta cuadra del Jr. Junín s/n, en el Cercado de Lima. Funciona en el antiguo local del Senado Nacional, el que durante el Virreinato había servido de sede al Tribunal de la Inquisición. El edificio es un Monumento Nacional y forma parte del patrimonio cultural del país. Además, ha estado vinculado al Congreso de la República desde los días del primer Congreso Constituyente del Perú, cuando en sus ambientes se reunían sus miembros, alojándose inclusive en él numerosos Diputados. -

Arquitectura Prehispánica De Tierra: Conservación Y Uso Social En Las Huacas De Moche, Perú

Arquitectura prehispánica de tierra: conservación y uso social en las Huacas de Moche, Perú Ricardo Morales Gamarra Génesis de un proyecto de investigación subtropical (dd-S), carente de árboles en el flan- vol. 20, núm. 2 (2007): 256-277 interdisciplinaria co sur y, por lo tanto, expuesto a los fuertes vientos alisios y su carácter abrasivo y contaminante, por APUNTES El Complejo Arqueológico Huacas de Moche estu- la arena y material particulado que acarrea desde 256 El presente documento vo en completo abandono y expuesto al cotidiano el litoral. Precisamente por este factor meteoro- reporta un avance del saqueo hasta mayo de 1991, fecha en que el lógico, los edificios sacros moche y chimú están proceso de investigación y evaluación del Proyecto Proyecto de Investigación y Conservación inicia orientados hacia el norte. Este sitio fue el centro de Conservación sus labores de campo, en el marco institucional rector de la sociedad moche que se desarrolló en Arqueológica y Uso de la Universidad Nacional de Trujillo y con el la costa norte del Perú (figura 1) desde los inicios Social de la Huaca de la Luna, Valle de Moche, financiamiento de la Fundación Ford de Estados de nuestra era hasta el siglo VIII, constituyéndo- en la costa norte del Unidos. Meses antes, el 20 de octubre de 1990, se en su tiempo en el centro urbano-ceremonial Perú, un monumento arquitectónico preinca descubrí los primeros relieves polícromos en el más importante de la macro región norte de los construido en tierra, con flanco sur de Huaca de la Luna y, gracias a este Andes centrales. -

Estudio Del Plan Maestro De Desarrollo Turístico Nacional En La República Del Perú (Fase 2)

No. Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Ministerio de Industria, Turismo, Integración y Negociaciones Comerciales Internacionales (MITINCI) Estudio del Plan Maestro de Desarrollo Turístico Nacional en la República del Perú (Fase 2) Informe Final Volumen 3: Proyectos y Programas SSF JR Enero, 2001 Pacific Consultants International 00-211 Volume 3 Projects and Programs Tabla de Contenido 1. Corredor Turístico Trujillo – Chiclayo...............................................................................1 1.1. Sub-proyectos Prioritarios.............................................................................................1 1.1.1. Construcción de la Nueva Carretera de Evitamiento de Trujillo............................1 1.1.2. Desarrollo del Parque Arqueológico de Chan Chan ..............................................6 1.1.3. Mejoramiento Turístico de los Sitios Arqueológicos de las Huacas del Sol y de la Luna .......................................................................................................... 12 1.1.4. Desarrollo del “Parque del Baluarte”.................................................................. 17 1.1.5. Mejoramiento Turístico de El Brujo ................................................................... 22 1.1.6. Embellecimiento y Conservación del Centro Histórico de Pacasmayo................ 26 1.1.7. Mejoramiento del Circuito Carretero entre Ferreñafe y Cayalti vía Huaca Rajada..................................................................................................... 30 1.1.8. -

Facultad De Arquitectura Carrera De Arquitectura

FACULTAD DE ARQUITECTURA CARRERA DE ARQUITECTURA CENTRO DE INTERPRETACIÓN COMO APORTE PARA LA PUESTA EN VALOR DEL COMPLEJO ARQUEOLÓGICO GARAGAY. Tesis para optar el título profesional de: Arquitecto Autor: Bach. Arq. Julio Edwin Alva Pimentel Asesor: Arq. Israel Leandro Flores Lima – Perú 2018 CENTRO DE INTERPRETACIÓN COMO APORTE PARA LA PUESTA EN VALOR DEL COMPLEJO ARQUEOLÓGICO GARAGAY APROBACIÓN DE LA TESIS El asesor y los miembros del jurado evaluador asignados, APRUEBAN la tesis desarrollada por el Bachiller Julio Edwin Alva Pimentel, denominada: CENTRO DE INTERPRETACIÓN COMO APORTE PARA LA PUESTA EN VALOR DEL COMPLEJO ARQUEOLÓGICO GARAGAY Arq. Israel Leandro Flores Arq. Nombres y Apellidos ASESOR Arq. Daniel Maya Garavito Arq. Nombres y Apellidos JURADO PRESIDENTE Arq. Luis Rosselló Vera Arq. Nombres y Apellidos JURADO Arq. Arturo Valdivia Loro Arq. Nombres y Apellidos JURADO Alva Pimentel, Julio Edwin ii CENTRO DE INTERPRETACIÓN COMO APORTE PARA LA PUESTA EN VALOR DEL COMPLEJO ARQUEOLÓGICO GARAGAY DEDICATORIA Esta investigación está dirigida hacia la gente que, como yo, busca que su país crezca con un legado histórico patrimonial bien protegido. Mediante la investigación y recuperación y conservación de elementos patrimoniales, como las huacas, se puede lograr establecer una identidad conjunta en la actualidad y poder contar la historia de su pasado a la población del futuro. Dirigido para gente de distintas disciplinas, que valoran el patrimonio que el Perú posee, sintiéndose orgullosa de vivir cerca de una huaca y buscando recuperarla, valorando su presencia y mejorando el entorno donde viven por medio del aumento del valor cultural que poseen, estableciendo un legado y formando consciencia de la historia.