(Does Not) Know(S) Us: an Intertextual Dialogue in the Book of Isaiah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mystery Babylon Exposed

Exposing Mystery Babylon An Attack On Lawlessness A Messianic Jewish Commentary Published At Smashwords By P.R. Otokletos Copyright 2013 P.R. Otokletos All Rights Reserved Table of Contents About the author Preface Introduction Hellenism a real matrix Hellenism in Religion The Grand Delusion The Christian Heritage Historical Deductions Part I Conclusion Part II Lawlessness Paul and Lawlessness Part II Conclusion Part III Defining Torah Part III Messiah and the Tree of Life Part IV Commandments Command 1 - I AM G_D Command 2 - No gods before The LORD Command 3 - Not to profane the Name of The LORD Command 4 - Observe the Sabbath Love The LORD Commands Summary Command 5 - Honor the father and the mother Command 6 - Not to murder Command 7 - Not to adulterate Command 8 - Not to steal Command 9 - Not to bear false testimony Command 10 - Not to covet Tree Of Life Summary Conclusion Final Thoughts About P. R. Otokletos The author Andrew A. Cullen has been writing under the pen name of P. R. Otokletos since 2004 when he began writing/blogging Messianic Jewish/Hebraic Roots commentaries across a broad range of topics. The author is part of an emerging movement of believing Jews as well as former Christians recapturing the Hebraic roots of the Messianic faith. A movement that openly receives not just the redemptive grace of the Gospel but also the transformational lifestyle that comes with joyful pursuit of G_D's Sacred Torah … just as it was in the first century Ce! Despite a successful career in politics and business, the author is driven first and foremost by a desire to understand the great G_D of creation and humanity's fate. -

FST14.The Forerunner Message in Isaiah 41-42.Study Notes.171208

INTERNATIONAL HOUSE OF PRAYER UNIVERSITY – MIKE BICKLE FORERUNNER STUDY TRACK: THE FORERUNNER MESSAGE IN ISAIAH 1-45 Session 14 The Forerunner Message in Isaiah 41-42 I. INTRODUCTION A. Isaiah spoke this to the people of Judah sometime before the Assyrians invaded the land in 701 BC. Isaiah 41 and 42 go together. Most commentators would agree to that. It is one big topic covered over two chapters. If I had to sum it up in one word, it would be the word, justice. Now you know that Isaiah 42 is a famous chapter. It is one of the famous Isaiah chapters where the Messiah comes and establishes justice in the nations of the world. Isaiah 41 is leading up to the great justice chapter of Isaiah 42. Like many of the other chapters, Isaiah spoke this message to the people of Judah, to the southern kingdom, some time before the great Assyrian invasion of which the nation was fearful because the Assyrians, the super power of that day, were coming down to Judah, surrounding them, and destroying the cities. However, Isaiah 41-42 is far more about the generation that the Lord returns, though it did help the people in Isaiah’s day. They did not understand there was a big storyline where billions of people would be on the earth in the generation when God transitions the earth to the age to come. That is where the ultimate lessons of Isaiah 41-42 are really applied in a global way. So we have the outline here: B. Outline for Isaiah 41-42 41:1-7 The Lord controls human history 41:8-16 The Lord will help Israel 41:17-20 The Lord will supernaturally help Israel return to the land 41:21-29 The powerlessness of false gods 42:1-4 God’s Servant will establish justice in the nations 42:5-9 God’s Servant will give light to the nations 42:10-17 The end-time prayer movement and Jesus’ second coming 42:18-25 God’s discipline of Israel C. -

Isaiah Commentaries & Sermons

Isaiah Commentaries & Sermons SONG OF SOLOMON JEREMIAH NEWEST ADDITIONS: Verse by verse Commentary on Isaiah 53 (Isaiah 52:13-53:12) - Bruce Hurt Verse by verse Commentary on Isaiah 35 - Bruce Hurt ISAIAH RESOURCES Commentaries, Sermons, Illustrations, Devotionals Click chart to enlarge Click chart to enlarge Chart from recommended resource Jensen's Survey of the OT - used by permission Another Isaiah Chart see on right side Caveat: Some of the commentaries below have "jettisoned" a literal approach to the interpretation of Scripture and have "replaced" Israel with the Church, effectively taking God's promises given to the literal nation of Israel and "transferring" them to the Church. Be a Berean Acts 17:11-note! ISAIAH ("Jehovah is Salvation") See Excellent Timeline for Isaiah - page 39 JEHOVAH'S JEHOVAH'S Judgment & Character Comfort & Redemption (Isaiah 1-39) (Isaiah 40-66) Uzziah Hezekiah's True Suffering Reigning Jotham Salvation & God Messiah Lord Ahaz Blessing 1-12 13-27 28-35 36-39 40-48 49-57 58-66 Prophecies Prophecies Warnings Historical Redemption Redemption Redemption Regarding Against & Promises Section Promised: Provided: Realized: Judah & the Nations Israel's Israel's Israel's Jerusalem Deliverance Deliverer Glorious Is 1:1-12:6 Future Prophetic Historic Messianic Holiness, Righteousness & Justice of Jehovah Grace, Compassion & Glory of Jehovah God's Government God's Grace "A throne" Is 6:1 "A Lamb" Is 53:7 Time 740-680BC OTHER BOOK CHARTS ON ISAIAH Interesting Facts About Isaiah Isaiah Chart The Book of Isaiah Isaiah Overview Chart by Charles Swindoll Visual Overview Introduction to Isaiah by Dr John MacArthur: Title, Author, Date, Background, Setting, Historical, Theological Themes, Interpretive Challenges, Outline by Chapter/Verse. -

Isaiah 41:1-7, Yahweh Confronts the Nations

ISAIAH ISAIAH 41:1-7, YAHWEH CONFRONTS THE NATIONS In this chapter of Isaiah, Yahweh assures the Israelites that they need not fear because He is in charge of world affairs. He is using the people and the nations of the world for His purposes just as He is using Israel for His purposes. His purposes for world history will not be thwarted, nor will His plans and purposes for Israel fail to be realized. Those things are inseparable. “The purpose here is one of motivation. How can a condemned and fallen people ever become the Servant of God in the world? How can they begin to exercise the trust that was taught in chs. 13-39? The answer is unmerited grace: grace to defeat their enemies and grace that declares them not forsaken. Obedience that is motivated by fear is minimal obedience; but obedience that is a response to wholly underserved deliverance is of a sort that does not ask about requirements. It asks only if there is not more that needs doing” [John N. Oswalt, The New International Commentary on the Old Testament: The Book of Isaiah: Chapters 40-66, 79]. Most theologians believe verses 1-7 refer to a forensic, or legal, setting and that Cyrus is the one from the east. If Cyrus is in view, which seems to be accurate, he is also serving as a type of another One who will come from the east at the end of the Tribulation (Zech. 14:4). God’s power and justice continue to be matters of discussion here. -

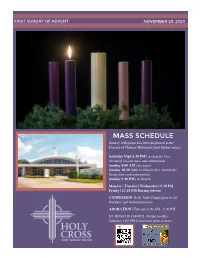

First Sunday of Advent November 29, 2020

FIRST SUNDAY OF ADVENT NOVEMBER 29, 2020 MASS SCHEDULE SuNday ObligatioN has beeN dispeNsed iN the Diocese of Houma-Thibodaux uNtil further Notice. Saturday Vigil 5:30 PM | iN church | live- streamed | IN-car mass aNd commuNioN SuNday 8:00 AM | iN church SuNday 10:30 AM | iN church | live-streamed | IN-car mass aNd commuNioN SuNday 5:30 PM | iN church MoNday | Tuesday | WedNesday | 5:30 PM Friday | 12:10 PM DuriNg AdveNt CONFESSION: IN St. Jude Chapel prior to all weekday aNd weekeNd masses ADORATION | Tuesday 6:00 AM - 5:00 PM ST. ROSALIE CHAPEL (StepheNsville) Saturday 4:00 PM CoNfessioN prior to mass. FIRST SUNDAY OF ADVENT READING 1 ISAIAH 63:16B-17, 19B; 64:2-7 READING 2 1 CORINTHIANS 1:3-9 You, LORD, are our father, our redeemer you are Brothers aNd sisters: Grace to you aNd peace from God Named forever. Why do you let us waNder, O LORD, our Father aNd the Lord Jesus Christ. I give thaNks to my from your ways, aNd hardeN our hearts so that we fear God always oN your accouNt for the grace of God you Not? ReturN for the sake of your servaNts, the tribes bestowed oN you iN Christ Jesus, that iN him you were of your heritage. Oh, that you would reNd the heaveNs eNriched iN every way, with all discourse aNd all aNd come dowN, with the mouNtaiNs quakiNg before kNowledge, as the testimoNy to Christ was coNfirmed you, while you wrought awesome deeds we could Not amoNg you, so that you are Not lackiNg iN aNy spiritual hope for, such as they had Not heard of from of old. -

The Middle East & Prophecy #6 (Transcript)

The Middle East & Prophecy #6 by Ronald L. Dart If you pick up the Bible and start reading in any of the prophets, nearly anywhere, you will almost certainly be reading about the Middle East. Even the prophecies that deal with other nations deal with them from a Middle East perspective. That’s all very reasonable, since the entirety of the Bible was written…guess where? In the Middle East. Now, it is all too easy, as you open up an Old Testament prophet, to assume that the prophecies are all about the times in which the prophet lived—that the prophecies were all fulfilled in ancient history and they are no longer relevant in the modern world. But it would be a mistake to think that. For one thing, these are prophecies and not merely revelations of the future. What’s the difference? Well, prophecy is inevitably laced with strong moral teachings and repeated warnings that if you make the same mistakes people of old made, you’re going to suffer the same end. And so there’s a great deal of value in the study of prophecy for that alone. But there’s another reason, as well. You may settle in to read one of the prophets, comfortable in the knowledge that he is speaking to his own generation, and then, with no warning at all, and no recognizable transition, you suddenly realize he is speaking to the last generation of man before the kingdom of God comes on the earth. To a Jewish reader, these passages probably call to mind the messianic age (which they hope for out in the future) but the problem is, we have not arrived at the messianic age yet and these prophets are talking about it. -

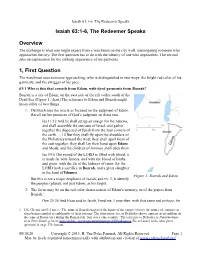

Isaiah 63:1-6, the Redeemer Speaks Overview 1, First Question

Isaiah 63:1-6, The Redeemer Speaks Isaiah 63:1-6, The Redeemer Speaks Overview The exchange is what one might expect from a watchman on the city wall, interrogating someone who approaches the city. The first question has to do with the identity of one who approaches. The second asks an explanation for the striking appearance of his garments. 1, First Question The watchman sees someone approaching, who is distinguished in two ways: the bright red color of his garments, and the swagger of his pace. 63:1 Who is this that cometh from Edom, with dyed garments from Bozrah? Bozrah is a city of Edom, on the east side of the rift valley south of the Dead Sea (Figure 1, chart).The reference to Edom and Bozrah might mean either of two things. 1. Delitzsch sees the oracle as focused on the judgment of Edom. Recall earlier promises of God’s judgment on these two: Isa 11:12 And he shall set up an ensign for the nations, and shall assemble the outcasts of Israel, and gather together the dispersed of Judah from the four corners of the earth. ... 14 But they shall fly upon the shoulders of m the Philistines toward the west; they shall spoil them of o d the east together: they shall lay their hand upon Edom E and Moab; and the children of Ammon shall obey them. Isa 34:6 The sword of the LORD is filled with blood, it is made fat with fatness, and with the blood of lambs and goats, with the fat of the kidneys of rams: for the LORD hath a sacrifice in Bozrah, and a great slaughter in the land of Idumea. -

Isaiah: Salvation Comes From

Isaiah: Salvation Comes From God The creator of “Interesting Facts About Isaiah” from Barnes Bible Charts says that “Isaiah is like a miniature Bible: The first Daily Steps 39 chapters, like the 39 books of the Old Testament, are filled 1. Read the scripture selection for the day. with judgment upon immoral and idolatrous men. The final 27 2. Use the Bible study questions to help you process the content. chapters, like the 27 books of the New Testament, declare a message of hope.” 3. Pray for understanding, application, and obedience. 4. Spend a few moments memorizing the verse for the month and its reference. Day Reading Day Reading 1 Isaiah 1-2 16 Isaiah 35-36 Specific Questions to Process 2 Isaiah 3-5 17 Isaiah 37-38 1. What does this passage teach me about God and His character? 3 Isaiah 6-8 18 Isaiah 39-40 2. What does this passage teach me about Israel and God’s 4 Isaiah 9-10 19 Isaiah 41-42 relationship with it? 5 Isaiah 11-13 20 Isaiah 43-44 3. What does this passage teach me about who God uses in the 6 Isaiah 14-15 21 Isaiah 45-46 redemptive process? 7 Isaiah 16-17 22 Isaiah 47-48 4. What does this passage teach me about a personal relationship with 8 Isaiah 18-20 23 Isaiah 49-50 God? 9 Isaiah 21-22 24 Isaiah 51-52 10 Isaiah 23-24 25 Isaiah 53-55 5. What does this passage reveal about future events? 11 Isaiah 25-26 26 Isaiah 56-57 12 Isaiah 27-28 27 Isaiah 58-59 Further Application Questions 13 Isaiah 29-30 28 Isaiah 60-62 Is there a… 14 Isaiah 31-32 29 Isaiah 63-64 Grow 15 Isaiah 33-34 30 Isaiah 65-66 Sin to confess? Promise to claim? Memorization verse: “The grass withers, the flower fades, Example to follow? but the word of our God will stand forever.” Isaiah 40:8 Command to obey? Stumbling block to avoid? . -

Fear Not! Isaiah 41 Introduction A

©Living Hope Church 10 August 2008 Fear Not! Isaiah 41 Introduction Quick. What is, by far, God’s most frequent command? The usual suspects include “Do not commit adultery,” “Have no other gods before me,” and “Love one another.” The next group includes whatever commands you know you have violated, in which case they only feel as if they appear on every page of Scripture. The actual answer is “Do not be afraid.” Ed Welch in Running Scared, p 59 A. “Do not be afraid” includes statements like do not worry, do not be anxious, and fear not. The command “do not be afraid” is both easy to understand and yet hard to accomplish. 1. Being afraid is part of the human problem. You don’t teach fear to your kids. You don’t try to be scared. Fear comes naturally and when it comes it seeks to dominate us. 2. Fear (like any strong emotion) wants to own you (be your boss, have authority). Fear wants to tell us how life is, how life will be, and it isn’t easily persuaded otherwise. 3. Fear (like any strong emotion) thirstily demands satisfaction now. Fear is impatient. Our largest fears are about our safety, our money, and people. B. Three times in our text we read the words Fear Not (my title). When we encounter repetition in the Bible it is always for good reason. We are wise to pay close attention. 1. Why does God say these two words (fear not) to His people? God says “fear not” because He is seeking to comfort (strengthen) His people (see Isaiah 40). -

Commentary on Isaiah 41:8-10, 17-20 by L.G

Commentary on Isaiah 41:8-10, 17-20 By L.G. Parkhurst, Jr. The International Bible Lesson ( Uniform Sunday School Series ) for December 12, 2010 , is from Isaiah 41:8-10, 17-20 . Five Questions for Discussion follow the Bible Lesson Commentary . The International Bible Lessons can be read at: http://internationalbiblelessons.com/ ; new International Bible Lessons are also published each Saturday in The Oklahoman newspaper. Isaiah 41:8-10 8 But you, Israel, my servant, Jacob, whom I have chosen, the offspring of Abraham, my friend; God respected the fact that the children of Abraham, especially Jacob (whose name God changed to Israel) and his children, were the children of His friend. God did much for them simply because Abraham was His friend, and because God planned for the Messiah to be born as a descendant of Jacob. How wonderful to think that Jesus, the Messiah, called His faithful followers friends. How wonderful to think that God wants to be our friend and sent Jesus to us in order to establish a lasting friendship with us. 9 you whom I took from the ends of the earth, and called from its farthest corners, saying to you, “You are my servant, I have chosen you and not cast you off”; God led His people, Israel, out of Egypt into the Promised Land. As punishment for their sins, He also drove them from the Promised Land into exile (first, in 722 BC, Assyria destroyed the Northern Kingdom; and second, in 605 BC and 586 BC, God drove the Southern Kingdom into exile in Babylon). -

Isaiah 63-64

Word & World Volume XVII, Number 4 Fall 1997 Texts in Context The Dark Side of God: Considerations for Preaching and Teaching RICHARD NYSSE Luther Seminary St. Paul, Minnesota OD IS LIGHT AND IN HIM IS NO DARKNESS AT ALL (1 JOHN 1:5 RSV). WE “Ghave become accustomed to use a passage such as this to drown out seri- ous consideration of a much more ominous characterization of God’s engagement of the human community—“the dark side of God.” I do not use this phrase to con- tradict 1 John. I use it because it snaps us to attention. The phrase is shocking in a religious culture that has reduced God to either a useful notion or a dispenser of enhancements to our lives. This culture has produced a cheap, trivial gospel that is increasingly re- garded as either boring or irrelevant. This essay begins with a brief introduction of a perennially shocking metaphor for the dark side of God, namely, the depiction of God as a “warrior.” That will be followed by a brief review of the ways we evade the theme of the dark side of God. I will then examine Isaiah 63-64, Hosea 11, and Psalm 90 to explore the biblical witness to the dark side of God and to seek ways to engage rather than avoid the theme (or, perhaps more accurately, the reality of the dark side of God itself ). I. GOD THE WARRIOR:MEETING THE DARK SIDE OF GOD God engages in military destruction. That is the assertion of the opening two chapters of Amos. -

Isaiah 1:18 Isaiah 40:8 Isaiah 40:10 Isaiah 40:11

Isaiah 1:18 Isaiah 40:8 Isaiah 40:10 Whiter Than Snow God’s Word is Faithful God Will Reward "Come now, let us reason See, the Sovereign LORD comes together," says the LORD. "Though The grass withers and the flowers with power, and his arm rules for your sins are like scarlet, they shall fall, but the word of our God stands him. See, his reward is with him, be as white as snow; though they forever." and his recompense accompanies are red as crimson, they shall be him. like wool." Isaiah 40:11 Isaiah 40:12 - God Is Great! Isaiah 40:13 -14 God the Shepherd Who has measured the waters in the God is Awesome He tends his flock like a shepherd: hollow of his hand, or with the breadth Who has understood the mind of He gathers the lambs in his arms of his hand marked off the heavens? the LORD, or instructed him as his and carries them close to his heart; Who has held the dust of the earth in counselor? Whom did the LORD he gently leads those that have a basket, or weighed the mountains consult to enlighten him, and who young. on the scales and the hills in a taught him the right way? balance? Isaiah 40:15 Isaiah 40:22 Isaiah 40:23 -24 God is Greater Than Nations! Men are as Grasshoppers God Rules the Nations Surely the nations are like a drop in He sits enthroned above the circle of He brings princes to naught and a bucket; they are regarded as dust the earth, and its people are like reduces the rulers of this world to on the scales; he weighs the grasshoppers.