A Populist Monster and the Future of Constitutional Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1945 – PRELOM S PRETEKLOSTJO Zgodovina Srednjeevropskih Držav Ob Koncu Druge Svetovne Vojne

1945 – A BREAK WITH THE PAST A History of Central European Countries at the End of World War Two 1945 – PRELOM S PRETEKLOSTJO Zgodovina srednjeevropskih držav ob koncu druge svetovne vojne Edited by ZDENKO ČEPIČ Book Editor Zdenko Čepič Editorial board Zdenko Čepič, Slavomir Michalek, Christian Promitzer, Zdenko Radelić, Jerca Vodušek Starič Published by Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino/ Institute for Contemporary History, Ljubljana, Republika Slovenija/Republic of Slovenia Represented by Jerca Vodušek Starič Layout and typesetting Franc Čuden, Medit d.o.o. Printed by Grafika-M s.p. Print run 400 CIP – Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 94(4-191.2)"1945"(082) NINETEEN hundred and forty-five 1945 - a break with the past : a history of central European countries at the end of World War II = 1945 - prelom s preteklostjo: zgodovina srednjeevropskih držav ob koncu druge svetovne vojne / edited by Zdenko Čepič. - Ljubljana : Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino = Institute for Contemporary History, 2008 ISBN 978-961-6386-14-2 1. Vzp. stv. nasl. 2. Čepič, Zdenko 239512832 1945 – A Break with the Past / 1945 – Prelom s preteklostjo CONTENTS Zdenko Čepič, The War is Over. What Now? A Reflection on the End of World War Two ..................................................... 5 Dušan Nećak, From Monopolar to Bipolar World. Key Issues of the Classic Cold War ................................................................. 23 Slavomír Michálek, Czechoslovak Foreign Policy after World War Two. New Winds or Mere Dreams? -

Društvo Za Ustavno Pravo Slovenije

PRAVNA FAKULTETA UNIVERZE V LJUBLJANI IN USTAVNO SODIŠČE REPUBLIKE SLOVENIJE Mednarodna znanstvena konferenca Ljubljana, 21. in 22. december 2011 DVAJSET LET USTAVE REPUBLIKE SLOVENIJE: POMEN USTAVNOSTI IN USTAVNA DEMOKRACIJA Program konference Sreda, 21. december 2011 Pravna fakulteta v Ljubljani, Poljanski nasip 2 (zlata predavalnica) POMEN USTAVNOSTI IN USTAVNA DEMOKRACIJA Moderator: Prof. dr. Igor Kaučič Delovni jezik: slovenski 08.30 – 09.00 Prihod udeležencev 09.00 – 09.05 Otvoritev konference 09.05 – 09.15 Pozdravna nagovora Prof. dr. Peter Grilc, dekan Pravne fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani Prof. dr. Ernest Petrič, predsednik Ustavnega sodišča Republike Slovenije 09.15 – 09.45 Slavnostno predavanje Prof. dr. France Bučar: Dvajset let Ustave Republike Slovenije 09.45 – 11.00 Prof. dr. Peter Jambrek: Iskanje neusahljivega vira slovenske državnosti: zgodovinski procesi, travaux préparatoires, ustavni dokumenti? Prof. dr. Franc Grad: Ustavna ureditev organizacije državne oblasti Prof. dr. Lojze Ude: Svobodna gospodarska pobuda in poseganje države v gospodarstvo Mag. Matevž Krivic: Ali lahko še upamo v Ustavno sodišče? 11.00 – 11.15 Odmor 11.15 – 13.00 Prof. dr. Lovro Šturm: Vloga Ustavnega sodišča pri razmejitvi totalitarnega sistema in svobodne demokratične družbe temelječe na človekovem dostojanstvu in temeljnih svoboščinah Prof. dr. Dragica Wedam Lukić: Načelo sorazmernosti kot kriterij ustavnosodne presoje Jože Tratnik: Nekatera vprašanja o delu Ustavnega sodišča Prof. dr. Ivan Kristan: Referendumu vrniti legitimnost, Državnemu zboru pa avtoriteto Prof. dr. Igor Kaučič: Ustavnorevizijska dinamika: de constitutione lata in de constitutione ferenda 13.00 – 14.30 Kosilo 14.30 – 16.15 Prof. dr. Miro Cerar: Slovenska ustavna kultura (20 let kasneje) Prof. dr. Rajko Pirnat: Odprta vprašanja mandata ministra Prof. -

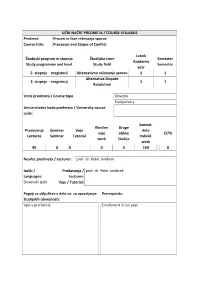

Procesi in Faze Reševanja Sporov Course Title: Processes and Stages of Conflict

UČNI NAČRT PREDMETA / COURSE SYLLABUS Predmet: Procesi in faze reševanja sporov Course title: Processes and Stages of Conflict Letnik Študijski program in stopnja Študijska smer Semester Academic Study programme and level Study field Semester year 2. stopnja - magisterij Alternativno reševanje sporov 1 1 Alternative Dispute 2. stopnja - magisterij 1 1 Resolution Vrsta predmeta / Course type Obvezni Compulsory Univerzitetna koda predmeta / University course code: Samost. Klinične Druge Predavanja Seminar Vaje delo vaje oblike ECTS Lectures Seminar Tutorial Individ. work študija work 40 0 0 0 0 160 8 Nosilec predmeta / Lecturer: prof. dr. Peter Jambrek Jeziki / Predavanja / prof. dr. Peter Jambrek Languages: Lectures: Slovenski jezik Vaje / Tutorial: Pogoji za vključitev v delo oz. za opravljanje Prerequisits: študijskih obveznosti: Vpis v prvi letnik. Enrollment in 1st year. Vsebina: Content (Syllabus outline): 1. Procesi alternativnega in 1. Alternative dispute resolution komplementarnega načina processes razreševanja sporov 2. The Mediation process and the stages 2. Mediacijski proces in faze mediacije of mediation 3. Vloga mediatorja in vloga 3. The role of the mediator and the role udeležencev v mediaciji of the participants in the mediation 4. Vodenje procesa mediacije in 4. The management of the process of komediacija mediation and comediation 5. Priprave na mediacijo (mediatorja, 5. Preparation for mediation (mediator, strank, odvetnikov) parties, lawyers) 6. Institut predmediacije 6. Institute of mediation 7. Pričetek mediacije in mediacijska 7. Start of mediation and mediation pogodba contract 8. Prva faza: uvodno srečanje 8. First phase: first meeting 9. Druga faza: raziskovanje v mediaciji 9. Second phase: research in mediation 10. Tretja faza: razreševanje in pogajanja 10. Third phase: resolution and 11. -

Slovenia's Self-Determination

UČNI NAČRT PREDMETA / COURSE SYLLABUS Predmet: Slovenska samoodločba Course title: Slovenia's Self-determination Študijski program in stopnja Študijska smer Letnik Semester Study programme and level Study field Academic year Semester Slovenski študiji II, 2. stopnja 1 2 Slovenian studies II, 2nd degree 1 2 Vrsta predmeta / Course type Obvezni / Obligatory Univerzitetna koda predmeta / University course code: FSMS-1-1-SS-PJ Predavanja Seminar Vaje Klinične vaje Druge oblike Samost. delo ECTS Lectures Seminar Tutorial work študija Individ. work 30 30 - - - 140 8 Nosilec predmeta / Lecturer: zasl. prof. dr. Peter Jambrek, zasl. prof. dr. Dimitrij Rupel Jeziki / Predavanja / slovenščina/Slovene Languages: Lectures: angleščina/English Slovenščina/ Vaje / Tutorial: slovenščina/Slovene Slovene angleščina/English Pogoji za vključitev v delo oz. za opravljanje Prerequisits: študijskih obveznosti: Prisotnost in sodelovanje na predavanjih in vajah: Active participation in lecture and tutorial. - prisotnost ni obvezna, sodelovanje na predavanjih - Attendance is not obligatory in vajah je pričakovano; - Constructive participation during lecture and - aktivnost in kakovost sodelovanja je po prosti tutorial time is expected and may represent by the presoji profesorja lahko sestavni del preizkusa choice of the professor elements in final examination znanja for the course Vsebina: Content (Syllabus outline): Predmet ima dve časovni razsežnosti: The course has two temporal dimensions: the zgodovinsko in sodobno. Glede na zgodovinsko historic and the contemporary -

© Nova Univerza, 2018 DIGNITAS Revija Za Človekove Pravice

DIGNITAS Revija za človekove pravice Slovenian journal of human rights ISSN 1408-9653 Komentar preambule ustave Republike Slovenije Peter Jambrek Article information: To cite this document: Jambrek, P. (2018). Komentar preambule ustave Republike Slovenije, Dignitas, št. 77/78, str. 5-28. Permanent link to this doument: https://doi.org/ 10.31601/dgnt/77/78-1 Created on: 16. 06. 2019 To copy this document: [email protected] For Authors: Please visit http://revije.nova-uni.si/ or contact Editors-in-Chief on [email protected] for more information. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. © Nova univerza, 2018 DIGNITAS n Komentar preambule ustave Republike Slovenije Komentar ustave Preambula Peter Jambrek Razglasitev Ker je izpolnjen pogoj iz tretjega odstavka 438. člena ustave Republike Slovenije, sprejema Skupščina Republike Slovenije na skupni seji vseh zborov dne 23. decembra 1991, na podlagi 440. člena ustave Republike Slovenije ODLOK O RAZGLASITVI USTAVE REPUBLIKE SLOVENIJE Razglaša se ustava Republike Slovenije, ki jo je sprejela Skupščina Republike Slovenije na seji Družbeno-politične- ga zbora dne 23. decembra 1991, na seji Zbora občin dne 23. decembra 1991 in na seji Zbora združenega dela dne 23. decembra 1991. PREAMBULA Izhajajoč iz Temeljne ustavne listine o samostojnosti in neodvisnosti Republike Slovenije, ter temeljnih človekovih pravic in svoboščin, temeljne in trajne pravice slovenskega naroda do samoodločbe, in iz zgodovinskega dejstva, da smo Slovenci v večstoletnem boju za narodno osvoboditev izoblikovali svojo narodno samobitnost in uveljavili svojo državnost, sprejema Skupščina Republike Slovenije Ustavo Republike Slovenije. 5 DIGNITAS n Komentar preambule ustave Republike Slovenije Pregled 1. -

Intervjujski Nagovori V Političnih Revijah 'Mladina' in 'Der Spiegel'

UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŽBENE VEDE Mirjana Pintar INTERVJUJSKI NAGOVORI V POLITIČNIH REVIJAH 'MLADINA' IN 'DER SPIEGEL' Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2006 UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŽBENE VEDE Mirjana Pintar Mentorica: izr. prof. dr. Monika Kalin Golob INTERVJUJSKI NAGOVORI V POLITIČNIH REVIJAH 'MLADINA' IN 'DER SPIEGEL' Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2006 Zahvala: Najlepše se zahvaljujem mentorici izr. prof. dr. Moniki Kalin Golob za pomoč, potrpežljivost in nasvete pri pisanju diplomskega dela. Intervjujski nagovori v političnih revijah ‘Mladina’ in ‘Der Spiegel’ Intervju je pogovor med osebama ali osebami za javnost, v katerem udeleženca intervjujskega dvogovora – vpraševalec in odgovarjalec – tvorita dvogovorno besedilo. Vpraševalec je spodbujevalec, usmerjevalec dvogovora in pri časopisnem intervjuju tudi zapisovalec intervjujskega besedila, ki poskuša od odgovarjalca, ki je v intervjujskem dvogovoru pasiven, saj le odgovarja na spodbude, dobiti za javnost pomembne informacije. V političnih intervjujih pogosto zasledimo neupoštevanje teh pravil, saj se politiki izmikajo odgovorom na provokativna vprašanja, odgovarjajo z vprašanji, komentirajo novinarjeva vprašanja, poskušajo preusmerjati pogovor in vpeljevati svoje teme ali odklanjajo odgovore. Novinarji ne postavljajo zgolj vprašanj v obliki vprašalnih povedi, ampak uporabljajo različne intervjujske nagovore, s katerimi spodbudijo odgovarjalca k odgovarjanju. Raznovrstnost intervjujskih nagovorov pripisujem sposobnosti dobrih novinarjev, ki kljub zahtevnim temam, o -

Bled, Slovenia, 26-27 November/Novembre 1999 CDL-STD(1999)029

Bled, Slovenia, 26-27 November/novembre 1999 CDL-STD(1999)029 Science and technique of democracy No. 29 Science et technique de la démocratie, n° 29 Bil. EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW COMMISSION EUROPEENNE POUR LA DEMOCRATIE PAR LE DROIT SOCIETIES IN CONFLICT: THE CONTRIBUTION OF LAW AND DEMOCRACY TO CONFLICT RESOLUTION SOCIETES EN CONFLIT : LA CONTRIBUTION DU DROIT ET DE LA DEMOCRATIE AU REGLEMENT DES CONFLITS TABLE OF CONTENTS / TABLE DES MATIERES OPENING SPEECH, Mr Vojko Volk........................................................................................................................... 2 OPENING SPEECH, Mr Serhiy Holovaty.................................................................................................................... 4 INDIVIDUAL AND COLLECTIVE SECURITY IN THE BALKANS, Mr Peter Jambrek........................................................................................................................ 5 ENSURING HUMAN SECURITY IN CONFLICT SITUATIONS, Mr Roman Kirn ........................................................................................................................ 20 LE ROLE DU DROIT INTERNATIONAL DANS LE REGLEMENT DES DIFFERENDS ENTRES ETATS, M. Constantin Economides ...................................................................................................... 23 MOLDOVA: TWO CONFLICTS WITH DIFFERENT HISTORIES, Mr Vladimir Solonari,.............................................................................................................. 28 THE NORTHERN IRELAND -

Unidem Seminar from the Electoral System

Strasbourg, 19 May 2004 CDL-UD(2004)008 Engl. only EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) in co-operation with THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA UNIDEM SEMINAR “EUROPEAN STANDARDS OF ELECTORAL LAW IN THE CONTEMPORARY CONSTITUTIONALISM” Sofia, 28-29 May 2004 FROM THE ELECTORAL SYSTEM REFERENDUM TO CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGES IN SLOVENIA (1996-2000) Report by Prof. dr. Ciril RIBI ČIČ (Judge, Constitutional Court of Slovenia) CDL-UD(2004)008 - 2 - 1. Characteristics of the Electoral System Referendum A referendum was held at the end of 1996 to decide whether to change the electoral system in Slovenia and replace it with one of the three proposals put forward. It was neither the first nor the last time that the fate of a country's electoral system was being decided at a referendum. Let me mention two examples that I have a special appreciation for. The first was the introduction of a combined double-vote electoral system based on the German system 1, introduced in New Zealand in a 1993 referendum. The second example is a set of two attempts to repeal the proportional electoral system by means of a single transferable vote in Ireland. Both attempts failed, which is surprising since the single transferable vote system is considered a system in which the division of votes is very complex to understand; it is appreciated in theory but unpopular with voters. I believe that its success at the Irish referendums - quite tight the first time and convincing the second time 2 - has to do with the fact that the extended use of a system can reduce its shortcomings. -

Draft Law on Religious Organisations in Serbia

. Strasbourg, 15 March 2005 CDL-AD (2005) 010 Opinion no. 334 / 2005 Engl.only EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) DRAFT LAW ON RELIGIOUS ORGANISATIONS IN SERBIA individual comments by Mr. Louis-Léon CHRISTIANS (Expert, Belgium) Mr. Peter JAMBREK (Member, Slovenia) endorsed by the Venice Commission at its 62nd Plenary Session (Venice, 11-12 March 2005) This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera pas distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire. CDL-AD(2005)010 - 2 - CONTENTS I. Introduction..................................................................................................................................4 II. Individual comments by Mr Louis-Léon Christians on the Draft Law on Religious Organisations in Serbia ...................................................................................................................5 1. The Scope of the Law ................................................................................................................5 Appraisal A: ...............................................................................................................................6 Appraisal B.................................................................................................................................7 2. Church Autonomy......................................................................................................................8 3. Freedom of Speech ....................................................................................................................9 -

Slovenia Political Briefing: Changes at the Far Right of the Political Spectrum Helena Motoh

ISSN: 2560-1601 Vol. 17, No. 1 (SI) April 2019 Slovenia political briefing: Changes at the far right of the political spectrum Helena Motoh 1052 Budapest Petőfi Sándor utca 11. +36 1 5858 690 Kiadó: Kína-KKE Intézet Nonprofit Kft. [email protected] Szerkesztésért felelős személy: Chen Xin Kiadásért felelős személy: Huang Ping china-cee.eu 2017/01 Changes at the far right of the political spectrum Summary In the last few years the right and far right of the political spectrum was mostly occupied by one of Slovenia's oldest and strongest political parties, the Slovenian Democratic Party, which started as centre-right political party but was increasing leaning towards populism and extreme right rhetoric. Although several prominent members had left the party in the two decades and some even established their own political parties, none of them went further right compared to the political positions of the original party. In the last month, two former members of SDS established a party which emulates the extreme right populist political positions of the Lega of Matteo Salvini in Italy. It is still unclear what shifts this move might cause on a wider political scene, especially before the May European Parliament elections. Background: Political shifts in the history of Slovenian Democratic Party Following the example of the Polish non-communist trade union Solidarność in early 1980s, an alternative trade union Neodvisnost (Independence) was formed following a big strike in Litostroj factory and – in relation to that – the political party called Social democratic union. First head of the party was France Tomšič, who was soon replaced by a former dissident and political émigré Jože Pučnik. -

The New Draft Treaty for the Constitution of the European Union

THE NEW DRAFT TREATY FOR THE CONSTITUTION OF THE EUROPEAN UNION The balanced Union of nations, civil societies, and market economies: Freedom within Union. Security for the Union. Justice for the Union’s citizens. THE NEW DRAFT TREATY FOR THE CONSTITUTION OF THE EUROPEAN UNION This draft Treaty for the Constitution of the European Union was prepared by Peter Jambrek to encourage discussion at the International Conference on the Constitutional Process for the European Union, held by the European Faculty of Law, Ljubljana (Slovenia), April 18th and 19th, 2016. Comments and critiques are welcome. Nova Gorica and Ljubljana, March 2016. CONTENTS I. PREAMBLE ............................................................................................................ 7 II. UNION OF NATIONS AND CITIZENS (art. 1–19) .................................................... 9 III. FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS (art. 20–64) ................................................................. 13 IV. LEGISLATIVE POWERS (art. 65–79) .................................................................... 21 V. EXECUTIVE POWERS (art. 80–94) ....................................................................... 27 VI. JUDICIAL POWERS (art. 95–120) ........................................................................ 31 VI. UNION’S FINANCIAL SYSTEM (art. 121–136) ...................................................... 37 VII. POWERS OF NATIONS AND THE UNION (art. 137–189) ..................................... 43 Legal acts of the Union (art. 137–141) ...................................................................... -

Novosti Maj 2018

MAJ 2018 06 KORPORACIJE, DRUŠTVA, RAZSTAVE, MUZEJI 1. MEDNARODNI simpozij Prostozidarstvo v Srednji Evropi (2017 ; Ljubljana) Skrivnost lože : zbornik prispevkov z mednarodnega simpozija Prostozidarstvo v Srednji Evropi, Narodni muzej Slovenije, Ljubljana, 11. maj 2017 / [glavni urednik Matevž Košir ; prevod Amidas ; fotograf Tomaž Lauko, Franci Virant]. - Ljubljana : Narodni muzej Slovenije, 2018 ([Ljubljana] : Januš). - 239 str. : ilustr., portreti, zvd. ; 25 cm ISBN 978-961-6981-26-2 COBISS.SI-ID 293818368 084.11+087.5 2. NILSSON, Ulf, 1948- Ko sva bila sama na svetu / [besedilo] Ulf Nilsson in [ilustracije] Eva Eriksson ; prevedla Danni Stražar. - 1. natis. - Hlebce : Zala, 2018 ISBN 978-961-6994-43-9 COBISS.SI-ID 294640640 159.9 PSIHOLOGIJA 3. UEXKÜLL, Jakob von Potikanja po okolnih svetovih živali in ljudi : slikanica nevidnih svetov / Jakob von Uexküll ; [avtor ilustracij Georg Kriszat ; prevod Samo Krušič ; spremna beseda Sebastjan Vörös]. - 1. izd. - Ljubljana : Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete, 2018 ([Ljubljana] : Birografika Bori). - 156 str. : ilustr. ; 21 cm Prevod dela: Streifzüge durch die Umwelten von Tieren und Menschen. - 200 izv. - Lahkotna potikanja po življenju in delu Jakoba von Uexkülla / Sebastjan Vörös: str. 121-151. - O avtorju na zadnjem zavihku ov. - Bibliografija k spremni besedi: str. 151-154 in opombe z bibliografijo na dnu str. - Kazalo ISBN 978-961-06-0062-6 COBISS.SI-ID 294327296 2 VERSTVO 4. MORGAN, Garry R. Religije sveta v 15 minutah na dan / Garry R. Morgan ; [prevod Tabita Jovanović]. - 1. izd. - Ljubljana : Podvig, 2018 ([Ljubljana] : Povše). - 198 str. ; 21 cm ISBN 978-961-93830-6-3 COBISS.SI-ID 294063616 31 DEMOGRAFIJA, SOCIOLOGIJA 5. STANKOVIĆ, Peter Politike popa : uvod v kulturne študije / Peter Stanković.