Unidem Seminar from the Electoral System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slovenia Before the Elections

PERSPECTIVE Realignment of the party system – Slovenia before the elections ALEŠ MAVER AND UROŠ URBAS November 2011 The coalition government under Social Democrat Prime make people redundant. Nevertheless, the unemploy- Minister Borut Pahor lost the support it needed in Parlia- ment rate increased by 75 per cent to 107,000 over three ment and early elections had to be called for 4 Decem- years. This policy was financed by loans of 8 billion eu- ber, one year before completing its term of office. What ros, which doubled the public deficit. are the reasons for this development? Which parties are now seeking votes in the »political marketplace«? What However, Prime Minister Pahor overestimated his popu- coalitions are possible after 4 December? And what chal- larity in a situation in which everybody hoped that the lenges will the new government face? economic crisis would soon be over. The governing par- ties had completely different priorities: they were seek- ing economic rents; they could not resist the pressure of Why did the government of lobbies and made concessions; and they were too preoc- Prime Minister Borut Pahor fail? cupied with scandals and other affairs emerging from the ranks of the governing coalition. Although the governing coalition was homogeneously left-wing, it could not work together and registered no significant achievements. The next government will thus Electoral history and development be compelled to achieve something. Due to the deterio- of the party system rating economic situation – for 2012 1 per cent GDP growth, 1.3 per cent inflation, 8.4 per cent unemploy- Since the re-introduction of the multi-party system Slo- ment and a 5.3 per cent budget deficit are predicted – venia has held general elections in 1990, 1992, 1996, the goals will be economic. -

The Case of Slovenia

“A Short History of Quotas in Slovenia” Sonja Lokar Chair, Gender Task Force of the Stability Pact for South Eastern Europe A paper presented at the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA)/CEE Network for Gender Issues Conference The Implementation of Quotas: European Experiences Budapest, Hungary, 22–23 October 2004 The Communist-dominated Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia was formed after the Second World War. Slovenia became the most developed of its six federal republics, gaining independence in the early 1990s. This case study looks at the participation of women in Slovenia before and after the break-up of the Former Yugoslavia, and examines the evolution of quota provisions that have been implemented to secure women’s participation in decision-making. Background Women in Slovenia were granted the universal right to vote for the first time in 1945, along with equality with men. At the beginning of the 1970s, some of Yugoslavia’s strongest Communist women leaders were deeply involved in the preparations for the first United Nations (UN) World Conference on Women in Mexico. They were clever enough to persuade old Communist Party leaders, Josip Broz Tito and his right-hand man Edvard Kardelj, that the introduction of the quota for women—with respect to the decision-making bodies of all political organizations and delegate lists—had implications for Yugoslavia’s international reputation.1 Communist women leaders worked hard to make Socialist Yugoslavia a role model (in terms of the emancipation of -

The Far Right in Slovenia

MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF SOCIAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE The Far Right in Slovenia Master‟s thesis Bc. Lucie Chládková Supervisor: doc. JUDr. PhDr. Miroslav Mareš, Ph.D. UČO: 333105 Field of Study: Security and Strategic Studies Matriculation Year: 2012 Brno 2014 Declaration of authorship of the thesis Hereby I confirm that this master‟s thesis “The Far Right in Slovenia” is an outcome of my own elaboration and work and I used only sources here mentioned. Brno, 10 May 2014 ……………………………………… Lucie Chládková 2 Acknowledgments I would like to express my gratitude to doc. JUDr. PhDr. Miroslav Mareš, Ph.D., who supervised this thesis and contributed with a lot of valuable remarks and advice. I would like to also thank to all respondents from interviews for their help and information they shared with me. 3 Annotation This master‟s thesis deals with the far right in Slovenia after 1991 until today. The main aim of this case study is the description and analysis of far-right political parties, informal and formal organisations and subcultures. Special emphasis is put on the organisational structure of the far-right scene and on the ideological affiliation of individual far-right organisations. Keywords far right, Slovenia, political party, organisation, ideology, nationalism, extremism, Blood and Honour, patriotic, neo-Nazi, populism. 4 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 7 2. Methodology ......................................................................................................................... -

Keynote Speech by the President of the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Slovenia, Mag

Keynote speech by the President of the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Slovenia, Mag. Miroslav Mozetič Independence and Unity Day, Cankar Hall, 23 December 2015 Oh, motherland, when God created you, He blessed you abundantly, saying: "Merry people in this place will dwell; song will be their language and joyous cries their song!" And it happened just as He said. Seeds of God had sprouted, ample fruit they bore - Heaven grew 'neath Triglav's mighty slopes (Ivan Cankar, Kurent) Your Excellency, Mr Borut Pahor, President of the Republic, Honourable Members of Parliament - the representatives of the people, Honourable representatives of the Executive and Judiciary, representatives of religious communities, “my beloved Slovenes,” and citizens! Let us ask ourselves today: Have we been successful at fulfilling the vision of Cankar? Or was it just a dream? Today is the right day for such a question, as we are celebrating the Independence and Unity Day in commemoration of that magnificent day 25 years ago, when on 23 December 1990 we replied to the plebiscite question: “Shall the Republic of Slovenia become an independent and sovereign state?” by saying: YES. And there were 1,289,369 of us who chose this answer. There were only 57,800 votes against. We can certainly state that on that day, Slovenes and other residents of the then Republic of Slovenia demonstrated unity, as well as a firm determination and courage of many to bring to life a dream of and longing for the establishment of our own state. We did not miss out on the historic opportunity offered to us. -

1945 – PRELOM S PRETEKLOSTJO Zgodovina Srednjeevropskih Držav Ob Koncu Druge Svetovne Vojne

1945 – A BREAK WITH THE PAST A History of Central European Countries at the End of World War Two 1945 – PRELOM S PRETEKLOSTJO Zgodovina srednjeevropskih držav ob koncu druge svetovne vojne Edited by ZDENKO ČEPIČ Book Editor Zdenko Čepič Editorial board Zdenko Čepič, Slavomir Michalek, Christian Promitzer, Zdenko Radelić, Jerca Vodušek Starič Published by Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino/ Institute for Contemporary History, Ljubljana, Republika Slovenija/Republic of Slovenia Represented by Jerca Vodušek Starič Layout and typesetting Franc Čuden, Medit d.o.o. Printed by Grafika-M s.p. Print run 400 CIP – Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 94(4-191.2)"1945"(082) NINETEEN hundred and forty-five 1945 - a break with the past : a history of central European countries at the end of World War II = 1945 - prelom s preteklostjo: zgodovina srednjeevropskih držav ob koncu druge svetovne vojne / edited by Zdenko Čepič. - Ljubljana : Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino = Institute for Contemporary History, 2008 ISBN 978-961-6386-14-2 1. Vzp. stv. nasl. 2. Čepič, Zdenko 239512832 1945 – A Break with the Past / 1945 – Prelom s preteklostjo CONTENTS Zdenko Čepič, The War is Over. What Now? A Reflection on the End of World War Two ..................................................... 5 Dušan Nećak, From Monopolar to Bipolar World. Key Issues of the Classic Cold War ................................................................. 23 Slavomír Michálek, Czechoslovak Foreign Policy after World War Two. New Winds or Mere Dreams? -

Slovenia Country Report BTI 2018

BTI 2018 Country Report Slovenia This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018. It covers the period from February 1, 2015 to January 31, 2017. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — Slovenia. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2018 | Slovenia 3 Key Indicators Population M 2.1 HDI 0.890 GDP p.c., PPP $ 32885 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 0.1 HDI rank of 188 25 Gini Index 25.7 Life expectancy years 81.1 UN Education Index 0.915 Poverty3 % 0.0 Urban population % 49.6 Gender inequality2 0.053 Aid per capita $ - Sources (as of October 2017): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2017 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2016. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary From January 2015 to January 2017, the political situation in Slovenia began to stabilize, although heated debates occurred and several ministers resigned or were replaced. -

Društvo Za Ustavno Pravo Slovenije

PRAVNA FAKULTETA UNIVERZE V LJUBLJANI IN USTAVNO SODIŠČE REPUBLIKE SLOVENIJE Mednarodna znanstvena konferenca Ljubljana, 21. in 22. december 2011 DVAJSET LET USTAVE REPUBLIKE SLOVENIJE: POMEN USTAVNOSTI IN USTAVNA DEMOKRACIJA Program konference Sreda, 21. december 2011 Pravna fakulteta v Ljubljani, Poljanski nasip 2 (zlata predavalnica) POMEN USTAVNOSTI IN USTAVNA DEMOKRACIJA Moderator: Prof. dr. Igor Kaučič Delovni jezik: slovenski 08.30 – 09.00 Prihod udeležencev 09.00 – 09.05 Otvoritev konference 09.05 – 09.15 Pozdravna nagovora Prof. dr. Peter Grilc, dekan Pravne fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani Prof. dr. Ernest Petrič, predsednik Ustavnega sodišča Republike Slovenije 09.15 – 09.45 Slavnostno predavanje Prof. dr. France Bučar: Dvajset let Ustave Republike Slovenije 09.45 – 11.00 Prof. dr. Peter Jambrek: Iskanje neusahljivega vira slovenske državnosti: zgodovinski procesi, travaux préparatoires, ustavni dokumenti? Prof. dr. Franc Grad: Ustavna ureditev organizacije državne oblasti Prof. dr. Lojze Ude: Svobodna gospodarska pobuda in poseganje države v gospodarstvo Mag. Matevž Krivic: Ali lahko še upamo v Ustavno sodišče? 11.00 – 11.15 Odmor 11.15 – 13.00 Prof. dr. Lovro Šturm: Vloga Ustavnega sodišča pri razmejitvi totalitarnega sistema in svobodne demokratične družbe temelječe na človekovem dostojanstvu in temeljnih svoboščinah Prof. dr. Dragica Wedam Lukić: Načelo sorazmernosti kot kriterij ustavnosodne presoje Jože Tratnik: Nekatera vprašanja o delu Ustavnega sodišča Prof. dr. Ivan Kristan: Referendumu vrniti legitimnost, Državnemu zboru pa avtoriteto Prof. dr. Igor Kaučič: Ustavnorevizijska dinamika: de constitutione lata in de constitutione ferenda 13.00 – 14.30 Kosilo 14.30 – 16.15 Prof. dr. Miro Cerar: Slovenska ustavna kultura (20 let kasneje) Prof. dr. Rajko Pirnat: Odprta vprašanja mandata ministra Prof. -

A History of Yugoslavia Marie-Janine Calic

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Book Previews Purdue University Press 2-2019 A History of Yugoslavia Marie-Janine Calic Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_previews Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Calic, Marie-Janine, "A History of Yugoslavia" (2019). Purdue University Press Book Previews. 24. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_previews/24 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. A History of Yugoslavia Central European Studies Charles W. Ingrao, founding editor Paul Hanebrink, editor Maureen Healy, editor Howard Louthan, editor Dominique Reill, editor Daniel L. Unowsky, editor A History of Yugoslavia Marie-Janine Calic Translated by Dona Geyer Purdue University Press ♦ West Lafayette, Indiana Copyright 2019 by Purdue University. Printed in the United States of America. Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file at the Library of Congress. Paperback ISBN: 978-1-55753-838-3 ePub: ISBN 978-1-61249-564-4 ePDF ISBN: 978-1-61249-563-7 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-1-55753-849-9. Originally published in German as Geschichte Jugoslawiens im 20. Jahrhundert by Marie-Janine Calic. © Verlag C.H.Beck oHG, München 2014. The translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften International–Translation Funding for Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Office, the collecting society VG WORT and the Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers & Booksellers Association). -

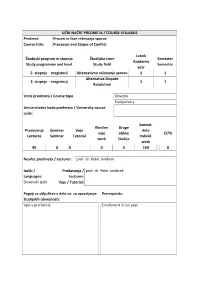

Procesi in Faze Reševanja Sporov Course Title: Processes and Stages of Conflict

UČNI NAČRT PREDMETA / COURSE SYLLABUS Predmet: Procesi in faze reševanja sporov Course title: Processes and Stages of Conflict Letnik Študijski program in stopnja Študijska smer Semester Academic Study programme and level Study field Semester year 2. stopnja - magisterij Alternativno reševanje sporov 1 1 Alternative Dispute 2. stopnja - magisterij 1 1 Resolution Vrsta predmeta / Course type Obvezni Compulsory Univerzitetna koda predmeta / University course code: Samost. Klinične Druge Predavanja Seminar Vaje delo vaje oblike ECTS Lectures Seminar Tutorial Individ. work študija work 40 0 0 0 0 160 8 Nosilec predmeta / Lecturer: prof. dr. Peter Jambrek Jeziki / Predavanja / prof. dr. Peter Jambrek Languages: Lectures: Slovenski jezik Vaje / Tutorial: Pogoji za vključitev v delo oz. za opravljanje Prerequisits: študijskih obveznosti: Vpis v prvi letnik. Enrollment in 1st year. Vsebina: Content (Syllabus outline): 1. Procesi alternativnega in 1. Alternative dispute resolution komplementarnega načina processes razreševanja sporov 2. The Mediation process and the stages 2. Mediacijski proces in faze mediacije of mediation 3. Vloga mediatorja in vloga 3. The role of the mediator and the role udeležencev v mediaciji of the participants in the mediation 4. Vodenje procesa mediacije in 4. The management of the process of komediacija mediation and comediation 5. Priprave na mediacijo (mediatorja, 5. Preparation for mediation (mediator, strank, odvetnikov) parties, lawyers) 6. Institut predmediacije 6. Institute of mediation 7. Pričetek mediacije in mediacijska 7. Start of mediation and mediation pogodba contract 8. Prva faza: uvodno srečanje 8. First phase: first meeting 9. Druga faza: raziskovanje v mediaciji 9. Second phase: research in mediation 10. Tretja faza: razreševanje in pogajanja 10. Third phase: resolution and 11. -

Slovenia's Self-Determination

UČNI NAČRT PREDMETA / COURSE SYLLABUS Predmet: Slovenska samoodločba Course title: Slovenia's Self-determination Študijski program in stopnja Študijska smer Letnik Semester Study programme and level Study field Academic year Semester Slovenski študiji II, 2. stopnja 1 2 Slovenian studies II, 2nd degree 1 2 Vrsta predmeta / Course type Obvezni / Obligatory Univerzitetna koda predmeta / University course code: FSMS-1-1-SS-PJ Predavanja Seminar Vaje Klinične vaje Druge oblike Samost. delo ECTS Lectures Seminar Tutorial work študija Individ. work 30 30 - - - 140 8 Nosilec predmeta / Lecturer: zasl. prof. dr. Peter Jambrek, zasl. prof. dr. Dimitrij Rupel Jeziki / Predavanja / slovenščina/Slovene Languages: Lectures: angleščina/English Slovenščina/ Vaje / Tutorial: slovenščina/Slovene Slovene angleščina/English Pogoji za vključitev v delo oz. za opravljanje Prerequisits: študijskih obveznosti: Prisotnost in sodelovanje na predavanjih in vajah: Active participation in lecture and tutorial. - prisotnost ni obvezna, sodelovanje na predavanjih - Attendance is not obligatory in vajah je pričakovano; - Constructive participation during lecture and - aktivnost in kakovost sodelovanja je po prosti tutorial time is expected and may represent by the presoji profesorja lahko sestavni del preizkusa choice of the professor elements in final examination znanja for the course Vsebina: Content (Syllabus outline): Predmet ima dve časovni razsežnosti: The course has two temporal dimensions: the zgodovinsko in sodobno. Glede na zgodovinsko historic and the contemporary -

© Nova Univerza, 2018 DIGNITAS Revija Za Človekove Pravice

DIGNITAS Revija za človekove pravice Slovenian journal of human rights ISSN 1408-9653 Komentar preambule ustave Republike Slovenije Peter Jambrek Article information: To cite this document: Jambrek, P. (2018). Komentar preambule ustave Republike Slovenije, Dignitas, št. 77/78, str. 5-28. Permanent link to this doument: https://doi.org/ 10.31601/dgnt/77/78-1 Created on: 16. 06. 2019 To copy this document: [email protected] For Authors: Please visit http://revije.nova-uni.si/ or contact Editors-in-Chief on [email protected] for more information. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. © Nova univerza, 2018 DIGNITAS n Komentar preambule ustave Republike Slovenije Komentar ustave Preambula Peter Jambrek Razglasitev Ker je izpolnjen pogoj iz tretjega odstavka 438. člena ustave Republike Slovenije, sprejema Skupščina Republike Slovenije na skupni seji vseh zborov dne 23. decembra 1991, na podlagi 440. člena ustave Republike Slovenije ODLOK O RAZGLASITVI USTAVE REPUBLIKE SLOVENIJE Razglaša se ustava Republike Slovenije, ki jo je sprejela Skupščina Republike Slovenije na seji Družbeno-politične- ga zbora dne 23. decembra 1991, na seji Zbora občin dne 23. decembra 1991 in na seji Zbora združenega dela dne 23. decembra 1991. PREAMBULA Izhajajoč iz Temeljne ustavne listine o samostojnosti in neodvisnosti Republike Slovenije, ter temeljnih človekovih pravic in svoboščin, temeljne in trajne pravice slovenskega naroda do samoodločbe, in iz zgodovinskega dejstva, da smo Slovenci v večstoletnem boju za narodno osvoboditev izoblikovali svojo narodno samobitnost in uveljavili svojo državnost, sprejema Skupščina Republike Slovenije Ustavo Republike Slovenije. 5 DIGNITAS n Komentar preambule ustave Republike Slovenije Pregled 1. -

Intervjujski Nagovori V Političnih Revijah 'Mladina' in 'Der Spiegel'

UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŽBENE VEDE Mirjana Pintar INTERVJUJSKI NAGOVORI V POLITIČNIH REVIJAH 'MLADINA' IN 'DER SPIEGEL' Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2006 UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŽBENE VEDE Mirjana Pintar Mentorica: izr. prof. dr. Monika Kalin Golob INTERVJUJSKI NAGOVORI V POLITIČNIH REVIJAH 'MLADINA' IN 'DER SPIEGEL' Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2006 Zahvala: Najlepše se zahvaljujem mentorici izr. prof. dr. Moniki Kalin Golob za pomoč, potrpežljivost in nasvete pri pisanju diplomskega dela. Intervjujski nagovori v političnih revijah ‘Mladina’ in ‘Der Spiegel’ Intervju je pogovor med osebama ali osebami za javnost, v katerem udeleženca intervjujskega dvogovora – vpraševalec in odgovarjalec – tvorita dvogovorno besedilo. Vpraševalec je spodbujevalec, usmerjevalec dvogovora in pri časopisnem intervjuju tudi zapisovalec intervjujskega besedila, ki poskuša od odgovarjalca, ki je v intervjujskem dvogovoru pasiven, saj le odgovarja na spodbude, dobiti za javnost pomembne informacije. V političnih intervjujih pogosto zasledimo neupoštevanje teh pravil, saj se politiki izmikajo odgovorom na provokativna vprašanja, odgovarjajo z vprašanji, komentirajo novinarjeva vprašanja, poskušajo preusmerjati pogovor in vpeljevati svoje teme ali odklanjajo odgovore. Novinarji ne postavljajo zgolj vprašanj v obliki vprašalnih povedi, ampak uporabljajo različne intervjujske nagovore, s katerimi spodbudijo odgovarjalca k odgovarjanju. Raznovrstnost intervjujskih nagovorov pripisujem sposobnosti dobrih novinarjev, ki kljub zahtevnim temam, o