Paper Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3. Acheampong 2910

Peer-Reviewed Article Volume 10, Issue SI (2021), pp. 39-56 Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education Special Issue: Schooling & Education in Ghana ISSN: 2166-2681Print 2690-0408 Online https://ojed.org/jise Promoting Assessment for Learning to Ensure Access, Equity, and Improvement in Educational Outcomes in Ghana Eugene Owusu-Acheampong Cape Coast Technical University, Ghana Olivia A. T. Frimpong Kwapong University of Ghana, Ghana ABSTRACT This study looked at assessment for learning as a criterion for promoting inclusiveness and equitable access to educational opportunities in Ghana. It compared assessment for learning and assessment of learning and recommended measures to evaluate students’ performance to allow for equitable access and progression in education. The study found the deployment of assessment of learning as discriminatory, restrictive, and ineffective for judging the overall worth of students after several years of learning. It is recommended that to ensure equitable access and fairness such that no child is left behind in the Ghanaian educational system, the criteria for progression of students be based on interest and academic strengths using assessment for learning approaches and not necessarily standardized tests. Keywords: access, assessment of learning, assessment for learning, educational outcomes, equity, formative, summative - 37 - INTRODUCTION Education is key to development. The heart of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which was adopted by the Member States of the United Nations in the year 2015, was the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. The fourth goal focuses on quality education (UN, n.d.). As noted by Kopnina (2020), the SDG Goal 4 on quality education expects all learners to acquire the knowledge and skills that are required for sustainable development. -

(SHS) and Quality University Education in Ghana: the Role of the University Teacher

E-ISSN 2240-0524 Journal of Educational and Social Research Vol 10 No 5 ISSN 2239-978X www.richtmann.org September 2020 . Research Article © 2020 Adu-Gyamfi et.al.. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) Free Senior High School (SHS) and Quality University Education in Ghana: The Role of the University Teacher Samuel Adu-Gyamfi1 Charles Ofosu Marfo2 Ali Yakubu Nyaaba1 Kwasi Amakye-Boateng1 Mohammed Abass1 Henry Tettey Yartey1 1Department of History and Political Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana 2Department of Language and Communication Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana DOI: https://doi.org/10.36941/jesr-2020-0101 Abstract Ghana’s education system has gone through several reforms in the post-independence period in the bid to increase access, ensure equity and quality at all levels (basic to tertiary). However, these goals seem to be a mirage especially on issues concerning quality at the secondary and tertiary levels. Against this backdrop, it has become imperative to raise relevant questions for the development of a new synthesis that is practical enough to allow for the necessary action to push forward the quality discourse which is a major concern among stakeholders. This paper intends to at least, serve the purpose of refreshing our memories concerning how we have individually or collectively, as citizens and academics, pondered over free secondary education, quality education and the role of the university teacher within the melting pot of the quality discourse in Ghana. -

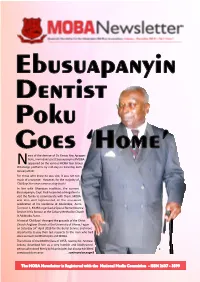

MOBA Newsletter 1 Jan-Dec 2019 1 260420 1 Bitmap.Cdr

Ebusuapanyin Dentist Poku Goes ‘Home’ ews of the demise of Dr. Fancis Yaw Apiagyei Poku, immediate past Ebusuapanyin of MOBA Nappeared on the various MOBA Year Group WhatsApp plaorms by mid-day on Saturday 26th January 2019. For those who knew he was sick, it was not too much of a surprise. However, for the majority of 'Old Boys' the news came as a big shock! In line with Ghanaian tradion, the current Ebusuapanyin, Capt. Paul Forjoe led a delegaon to visit the family to commiserate with them. MOBA was also well represented at the one-week celebraon at his residence at Abelenkpe, Accra. To crown it, MOBA organised a Special Remembrance Service in his honour at the Calvary Methodist Church in Adabraka, Accra. A host of 'Old Boys' thronged the grounds of the Christ Church Anglican Church at the University of Ghana, Legon on Saturday 24th April 2019 for the Burial Service and more importantly to pay their last respects to the man who had done so much for Mfantsipim and MOBA. The tribute of the MOBA Class of 1955, read by Dr. Andrew Arkutu, described him as a very humble and kindhearted person who stood firmly by his principles but always exhibited a composed demeanor. ...connued on page 8 The MOBA Newsletter is Registered with the National Media Commision - ISSN 2637 - 3599 Inside this Issue... Comments 5 Editorial: ‘Old Boys’ - Let’s Up Our Game 6 From Ebusuapanyin’s Desk Cover Story 8. Dr. Poku Goes Home 9 MOBA Honours Dentist Poku From the School 10 - 13 News from the Hill MOBA Matters 15 MOBA Elections 16 - 17 Facelift Campaign Contributors 18 - 23 2019 MOBA Events th 144 Anniversary 24 - 27 Mfantsipim Celebrates 144th Anniversary 28 2019 SYGs Project - Staff Apartments Articles 30 - 31 Reading, O Reading! Were Art Thou Gone? 32 - 33 2019 Which Growth? Lifestyle Advertising Space Available 34 - 36 Journey from Anumle to Kotokuraba Advertising Space available for Reminiscences businesses, products, etc. -

Kofi Annan Media Image (Mediální Obraz Kofiho Annana )

UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE FAKULTA HUMANITNÍCH STUDIÍ Katedra elektronické kultury a sémiotiky Nathan Wesley Kofi Annan Media Image (Mediální obraz Kofiho Annana ) Diplomová práce Studijní program: Mediální a komunika ční studia (7202T) Studijní obor: Elektronická kultura a sémiotika Vedoucí práce: Prof. PhDr. Miroslav Marcelli, Ph.D. Praha 2009 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem p ředkládanou práci zpracoval samostatn ě a použil jen uvedené prameny a literaturu. Sou časn ě dávám svolení k tomu, aby tato práce byla zp řístupn ěna v příslušné knihovn ě UK a prost řednictvím elektronické databáze vysokoškolských kvalifika čních prací v repozitá ři Univerzity Karlovy a používána ke studijním ú čel ům v souladu s autorským právem. V Praze dne 14. ledna 2008 Nathan Wesley SUMMARY ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................1 1. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................2 2. THESIS AND METHOD OF RESEARCH.....................................................4 3. THE UNITED NATIONS ORGANIZATION ................................................6 4. THE UN SECRETARY GENERAL ...............................................................8 4.1. KOFI ANNAN .........................................................................................9 5. MEDIA THEORY..........................................................................................12 5.1. BARTHES MYTHOLOGIES................................................................12 -

Afex #Bestsatpreponthecontinent Afex Sat Scores 2019

AFEX TEST PREP Preparing students for success in the changing world SAT SCORES 2019 THE HIGHEST POSSIBLE SAT SCORE IS 1600, 800 IN MATH 800 IN VERBAL OUT OF ALL TEST TAKERS IN THE WORLD VER NO NAME SCHOOL MATH BAL TOTAL PERCENTILE 1 SCHUYLER SEYRAM MFANTSIPIM SCHOOL 780 760 1540 TOP 1% 2 CHRISTOPHER OHRT LINCOLN COMMNUNITY SCHOOL 800 730 1530 TOP 1% 3 ADAMS ANAGLO ACHIMOTA SCHOOL 800 730 1530 TOP 1 % 4 JAMES BOATENG PRESEC, LEGON 800 730 1530 TOP 1% 5 GABRIEL ASARE WEST AFRICAN SENIOR HIGH 760 760 1520 TOP 1% 6 BLESSING OPOKU T. I. AHMADIYYA SNR. HIGH SCH 760 760 1520 TOP 1% 7 VICTORIA KIPNGETICH BROOKHOUSE INT’L SCH. - KENYA 760 750 1510 TOP 1% 8 EMMANUEL OPPONG PREMPEH COLLEGE 740 770 1510 TOP 1% 9 KWABENA YEBOAH ASARE S.O.S COLLEGE 780 730 1510 TOP 1% 10 SANDRA MWANGI ALLIANCE GIRLS' HIGH SCH.- KENYA 770 740 1510 TOP 1% 11 GEORGINA OMABOE CATE SCHOOL,USA 750 760 1510 TOP 1% 12 KUEI YAI BROOKHOUSE INT’L SCH. - KENYA 800 700 1500 TOP 1% 13 MICHAEL AHENKORA AKOSOMBO INTERNATIONAL SCH. 770 730 1500 TOP 1 % 14 KELVIN SARPONG S.O.S. COLLEGE 800 700 1500 TOP 1 % 15 AMY MIGUNDA ST ANDREW'S TURI - KENYA 790 710 1500 TOP 2 % 16 DESMOND ABABIO ST THOMAS AQUINAS 800 700 1500 TOP 1% 17 ALVIN OMONDI BROOKHOUSE INT’L SCH. - KENYA 790 700 1490 TOP 2 % 18 NANA K. OWUSU-MENSAH PRESEC LEGON 790 700 1490 TOP 2 % 19 CHARITY APREKU TEMA INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL 710 780 1490 TOP 2 % 20 LAURA LARBI-TIEKU GHANA CHRISTIAN INTERNATIONAL 770 720 1490 TOP 2 % 21 REUBEN AGOGOE ST THOMAS AQUINAS 790 700 1490 TOP 2 % 22 WILMA TAY GHANA NATIONAL COLLEGE 740 750 1490 TOP 2 % 23 BRANDON AMBETSA BROOKHOUSE INT’L SCH. -

Petrie, Jennifer Accepted Dissertation 08-20-15 Fa15.Pdf

Music and Dance Education in Senior High Schools in Ghana: A Multiple Case Study A dissertation presented to the faculty of The Patton College of Education of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education Jennifer L. Petrie December 2015 © 2015 Jennifer L. Petrie. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Music and Dance Education in Senior High Schools in Ghana: A Multiple Case Study by JENNIFER L. PETRIE has been approved for the Department of Educational Studies and The Patton College of Education by William K. Larson. Associate Professor of Educational Studies Renée A. Middleton Dean, The Patton College of Education 3 Abstract PETRIE, JENNIFER L., Ed.D., December 2015, Educational Administration Music and Dance Education in Senior High Schools in Ghana: A Multiple Case Study Director of Dissertation: William K. Larson This dissertation examined the state of senior high school (SHS) music and dance education in the context of a growing economy and current socio-cultural transitions in Ghana. The research analyzed the experience of educational administrators, teachers, and students. Educational administrators included professionals at educational organizations and institutions, government officials, and professors at universities in Ghana. Teachers and students were primarily from five SHSs, across varying socioeconomic strata in the Ashanti Region, the Central Region, and the Greater Accra Region. The study employed ethnographic and multiple case study approaches. The research incorporated the data collection techniques of archival document review, focus group, interview, observation, and participant observation. Four interrelated theoretical perspectives informed the research: interdisciplinary African arts theory, leadership and organizational theory, post- colonial theory, and qualitative educational methods’ perspectives. -

2017 Almanac Final Final.Cdr

THE METHODIST CHURCH GHANA CONFERENCE OFFICE, WESLEY HOUSE E252/2, LIBERIA ROAD P. O. BOX GP 403, ACCRA, TEL: 0302 670355 / 679223 WEBSITE: www.methodistchurch_gh.org Email: [email protected] PRESIDING BISHOP: THE MOST REV. TITUS K. AWOTWI PRATT, BA, MA LAY PRESIDENT: MR. KWAME AGYAPONG BOAFO, BA (HONS.), Q.C.L., BL. ADMINISTRATIVE BISHOP: THE RT REV. DR. PAUL KWABENA BOAFO, BA., PhD. DIOCESES BISHOPS LAY CHAIRMEN SYNOD SECRETARIES CAPE COAST The Rt. Rev. Ebenezer K. Abaka-Wilson, BA, MEd Bro. Titus D. Essel Very Rev. Richardson Aboagye Andam, BA MPhil ACCRA The Rt. Rev. Samuel K. Osabutey, BA., MA., PEM (ADR) Bro. Joseph K. Addo, CA, MBA Very Rev. Sampson N. A. M. Laryea Adjei, BTh KUMASI The Rt. Rev. Christopher N. Andam, BA., MSc., MBA Bro. Prof. Seth Opuni Asiama, BSc., PhD Very Rev. Stephen K. Owusu, BD, ThM, MPhil SEKONDI The Rt. Rev. Daniel De-Graft Brace, BA., MA Bro. George Tweneboah-Kodua, BEd, MSc Very Rev. Comfort Quartey-Papafio, MTS., ThM WINNEBA The Rt. Rev. Dr. J. K. Buabeng-Odoom, BEd., MEd., DMin Bro. Nicholas Taylor, BEd, MEd Very Rev. Joseph M. Ossei, BA., MPhil KOFORIDUA The Rt. Rev. Michael Agyakwa Bossman, BA., MPhil Bro. Samuel B. Mensah Jnr., BEd Very Rev. Samual Dua Dodd, BTh., D.Min SUNYANI The Rt. Rev. Kofi Asare Bediako, BA., MSc Sis. Grace Amoako Very Rev. Daniel K. Tannor, BA, MPhil TARKWA The Rt. Rev. Thomas Amponsah-Donkor, BA., LLB, BL Bro. Joseph K. Amponsah, BEd Very Rev. Nicholas Odum Baido, BA., MA NORTHERN GHANA The Rt. Rev. Dr. -

Primary 5 History of Ghana Facilitator's Guide

HISTORY OF GHANA for Basic Schools FACILITATOR’S GUIDE 5 • Bruno Osafo • Peter Boakye Published by WINMAT PUBLISHERS LTD No. 27 Ashiokai Street P.O. Box 8077 Accra North Ghana Tel.:+233 552 570 422 / +233 302 978 784 www.winmatpublishers.com [email protected] ISBN: 978-9988-0-4843-3 Text © Bruno Osafo, Peter Boakye 2020 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. Typeset by: Daniel Akrong Cover design by: Daniel Akrong Edited by: Akosua Dzifa Eghan and Eyra Doe The publishers have made every effort to trace all copyright holders but if they have inadvertently overlooked any, they will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page STRAND 2 My Country Ghana 1 Sub-Strand 1: The People of Ghana 1 Sub-Strand 5: Some Selected Individuals 12 STRAND 3 Europeans in Ghana 21 Sub-Strand 2: International Trade Including the Slave Trade 21 STRAND 4 Colonisation and Developments Under Colonial Rule In Ghana 26 Sub-strand 2: Social Developments Under Colonial Rule 26 Sub-strand 3: Economic Developments Under Colonial Rule 37 STRAND 5 Journey to Independence 45 Sub-Strand 1: Early Protest Movements 45 Sub-Strand 3: The 1948 Riots and After 52 Introduction This Facilitator’s Guide has been carefully written to help facilitators meet the expectations of the History of Ghana Curriculum designed by the Ministry of Education. -

Exploration of the Organizational Culture of Selected Ghanaian High Schools

Exploration of the Organizational Culture of Selected Ghanaian High Schools A dissertation presented to the faculty of The Patton College of Education of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education Grace Annor April 2016 © 2016 Grace Annor. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Exploration of Organizational Culture of Selected Ghanaian High Schools] by GRACE ANNOR has been approved for the Department of Educational Studies and The Patton College of Education by David Richard Moore Professor of Educational Studies Renée A. Middleton Dean, The Patton College of Education 3 Abstract ANNOR, GRACE, Ed.D., April 2016, Educational Administration Exploration of the Organizational Culture of Selected Ghanaian High Schools : Director of Dissertation: David Richard Moore The purpose of this study was to explore the organizational culture of two high schools in Ghana, examine the unique influence of cultural components on the schools’ outcomes, identify the exceptional contributions of the schools’ subcultures, investigate the emergent leadership styles of the schools’ leaders, and determine how these approaches promoted their work. This qualitative dissertation examined the various ways that the schools defined culture; how the schools’ subcultures participated in school governance; and how school leaders approached school governance. The description of the cultural components focused on the physical structures, symbols, behavior patterns, and verbal expressions, beliefs and values; and expectations. These descriptions were based on Edgar Schein’s diagnosis of the levels of culture. Efforts to improve school outcomes have not considered school culture, as a strategy in Ghana, neither has any educational research focused on the organizational culture of schools. -

History of Ghana Advisory Board

THE HISTORY OF GHANA ADVISORY BOARD John T. Alexander Professor of History and Russian and European Studies, University of Kansas Robert A. Divine George W. Littlefield Professor in American History Emeritus, University of Texas at Austin John V. Lombardi Professor of History, University of Florida THE HISTORY OF GHANA Roger S. Gocking The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations Frank W. Thackeray and John E. Findiing, Series Editors Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cocking, Roger. The history of Ghana / Roger S. Gocking. p. cm. — (The Greenwood histories of the modern nations, ISSN 1096-2905) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-313-31894-8 (alk. paper) 1. Ghana—History. I. Title. II. Series. DT510.5.G63 2005 966.7—dc22 2004028236 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2005 by Roger S. Gocking All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2004028236 ISBN: 0-313-31894-8 ISSN: 1096-2905 First published in 2005 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48-1984). 10 987654321 Contents Series Foreword vii Frank W. Thackeray and John -

Running Head: Ghana’S Demographic Transition and Demographic Dividend

Running Head: Ghana’s Demographic Transition and Demographic Dividend ASHESI UNIVERSITY The Demographic Transition and The Demographic Dividend: Does Ghana Stand A Chance? By Constance Awontayami Azong Undergraduate Thesis Report submitted to the Department of Business Administration, Ashesi University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award of Bachelor of Science degree in Business Administration May 2020 Running Head: Ghana’s Demographic Transition and Demographic Dividend ii DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and that no part of it has been presented for another degree in this university or elsewhere. Candidate’s Signature: …………………………………………………… Candidate’s Name: Constance Awontayami Azong Date: …………………………………………... I hereby declare that the preparation and presentation of this thesis was supervised in accordance with the guidelines on supervision of theses established by Ashesi University Supervisor’s Signature: …………………………… Supervisor’s Name: Dr. Stephen Emmanuel Armah Date: ………………………………………. Running Head: Ghana’s Demographic Transition and Demographic Dividend iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS “I have observed something else under the sun. The fastest runner doesn’t always win the race, and the strongest warrior doesn’t always win the battle. The wise sometimes go hungry, and the skillful are not necessarily wealthy. And those who are educated don’t always lead successful lives. It is all decided by chance, by being in the right place at the right time”. With much gratitude to the Lord for making this work complete. My profound gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Armah, for being there in every stage of my thesis, I say, God, bless you. An exceptional thanks to my lecturer, Ms. -

2017 Budget Highlights “Sowing the Seeds for Growth and Jobs”

www.pwc.com/gh 2017 Budget Highlights “Sowing the Seeds for Growth and Jobs” March 2017 Contents 2017 Budget Highlights 2 Commentary 2 At a Glance 6 The Economy 10 Direct Taxation 30 Indirect Taxation 34 Sectoral Outlook Overview 38 Appendix 1 50 Glossary 54 Our Leadership Team 57 PwC 2017 Budget Highlights 1 2017 Budget Highlights Commentary he much anticipated first budget statement of the Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo led government was finally presented to Parliament on 2 March 2017 under the theme “Sowing the seeds for growth and jobs”. The budget is anchored to the Tcountry’s medium term vision and priorities of Government, incorporates programmes initiated under the Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda II (“GSGDA II”), and is informed by the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (“SDGs”), and the African Union’s Agenda 2063. It is also set within the context of the IMF’s three-year Extended Credit Facility (“ECF”) programme with Ghana. Key policy objectives targeted in the medium-term include: a business- friendly and industrialised economy that creates jobs; a modernised agricultural sector that emphasises value addition and improved efficiencies; countrywide integrated infrastructure, and enhanced human capital. At PwC, in keeping with our practice for more than 15 years now, we have Vish Ashiagbor reviewed and analysed the budget statement, offered our independent Country Senior Partner views on Government’s policy intentions, proposed initiatives, and the 2017 economic targets. PwC Ghana The Hon. Minister of Finance, Mr Ken Ofori-Atta, noted that provisional data available indicates that economic performance in 2016 was weak.