Petrie, Jennifer Accepted Dissertation 08-20-15 Fa15.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ASANTE BEFORE 1700 Fay Kwasi Boaten*

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. 50. •# THE ASANTE BEFORE 1700 fay Kwasi Boaten* PEOPLING OF ASANTE • •*•• The name Asante appeared for the first time In any European literature at the beginning of the eighteenth century. This was the time when some Akan clans came to- gether to form a kingdom with Kumase as their capital,, some few years earlier. This apparently new territory was not the original home of the Asante. Originally all the ances- tors of the Asante lived at Adansc/Amansle.' The above assertion does not agree with Eva Meyerowitz's2 view that the Akan formerly lived along the Niger bend in the regions lying roughly between Djenne and Timbucto. There Is no evidence to support such mass migrations from outside.3 Adanse is therefore an important ancestral home of many Twi speakers. The area is traditionally known in Akan cosmogony as the place where God (Odomankoma) started the creation of the world, such as the ideas of the clan <snd kinship. Furthermore, Adanse was the first of the five principal Akan states of Adanse, Akyem Abuakwa, Assen, Denkyfra and Asante (The Akanman Piesle Num) In order of seniority.5 Evidence of the above claim for Adanse is shown by the fact that most of the ruling clans of the Akan forest states trace their origins to Adanse. -

Music of Ghana and Tanzania

MUSIC OF GHANA AND TANZANIA: A BRIEF COMPARISON AND DESCRIPTION OF VARIOUS AFRICAN MUSIC SCHOOLS Heather Bergseth A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERDecember OF 2011MUSIC Committee: David Harnish, Advisor Kara Attrep © 2011 Heather Bergseth All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Harnish, Advisor This thesis is based on my engagement and observations of various music schools in Ghana, West Africa, and Tanzania, East Africa. I spent the last three summers learning traditional dance- drumming in Ghana, West Africa. I focus primarily on two schools that I have significant recent experience with: the Dagbe Arts Centre in Kopeyia and the Dagara Music and Arts Center in Medie. While at Dagbe, I studied the music and dance of the Anlo-Ewe ethnic group, a people who live primarily in the Volta region of South-eastern Ghana, but who also inhabit neighboring countries as far as Togo and Benin. I took classes and lessons with the staff as well as with the director of Dagbe, Emmanuel Agbeli, a teacher and performer of Ewe dance-drumming. His father, Godwin Agbeli, founded the Dagbe Arts Centre in order to teach others, including foreigners, the musical styles, dances, and diverse artistic cultures of the Ewe people. The Dagara Music and Arts Center was founded by Bernard Woma, a master drummer and gyil (xylophone) player. The DMC or Dagara Music Center is situated in the town of Medie just outside of Accra. Mr. Woma hosts primarily international students at his compound, focusing on various musical styles, including his own culture, the Dagara, in addition music and dance of the Dagbamba, Ewe, and Ga ethnic groups. -

I the Use of African Music in Jazz from 1926-1964: an Investigation of the Life

The Use of African Music in Jazz From 1926-1964: An Investigation of the Life, Influences, and Music of Randy Weston by Jason John Squinobal Batchelor of Music, Berklee College of Music, 2003 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Ethnomusicology University of Pittsburgh 2007 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Jason John Squinobal It was defended on April 17, 2007 and approved by Dr. Nathan T. Davis, Professor, Music Department Dr. Akin Euba, Professor, Music Department Dr. Eric Moe, Professor, Music Department Thesis Director: Dr. Nathan T. Davis, Professor, Music Department ii Copyright © by Jason John Squinobal 2007 iii The Use of African Music in Jazz From 1926-1964: An Investigation of the Life, Influences, and Music of Randy Weston Jason John Squinobal, M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2007 ABSTRACT There have been many jazz musicians who have utilized traditional African music in their music. Randy Weston was not the first musician to do so, however he was chosen for this thesis because his experiences, influences, and music clearly demonstrate the importance traditional African culture has played in his life. Randy Weston was born during the Harlem Renaissance. His parents, who lived in Brooklyn at that time, were influenced by the political views that predominated African American culture. Weston’s father, in particular, felt a strong connection to his African heritage and instilled the concept of pan-Africanism and the writings of Marcus Garvey firmly into Randy Weston’s consciousness. -

“Sankofa Symbol” in New York's African Burial Ground Author(S): Erik R

Reassessing the “Sankofa Symbol” in New York's African Burial Ground Author(s): Erik R. Seeman Reviewed work(s): Source: The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 67, No. 1 (January 2010), pp. 101-122 Published by: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5309/willmaryquar.67.1.101 . Accessed: 15/02/2012 10:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The William and Mary Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org 98248_001_144 1/6/10 9:53 PM Page 101 Sources and Interpretations Reassessing the “Sankofa Symbol” in New York’s African Burial Ground Erik R. Seeman OR many decades scholars from disciplines including history, archaeology, and ethnomusicology have demonstrated the influence Fof African art, religion, music, and language on the cultures of the Americas. In the early years of this inquiry, scholars tended to identify dis- crete “survivals” of African culture in the Americas, pointing to a specific weaving pattern or syncopated rhythm or linguistic construction trans- ported from a particular African region to the New World. -

Teenage Pregnancy and Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Behavior in Suhum, Ghana1

European Journal of Educational Sciences, EJES March 2017 edition Vol.4, No.1 ISSN 1857- 6036 Teenage Pregnancy and Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Behavior in Suhum, Ghana1 Charles Quist-Adade, PhD Kwantlen Polytechnic University doi: 10.19044/ejes.v4no1a1 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/ejes.v4no1a1 Abstract This study sought to investigate the key factors that influence teenage reproductive and sexual behaviours and how these behaviours are likely to be influenced by parenting styles of primary caregivers of adolescents in Suhum, in Eastern Ghana. The study aimed to identify risky sexual and reproductive behaviours and their underlying factors among in-school and out-of-school adolescents and how parenting styles might play a role. While the data from the study provided a useful snapshot and a clear picture of sexual and reproductive behaviours of the teenagers surveyed, it did not point to any strong association between parental styles and teens’ sexual reproductive behaviours. Keywords: Parenting styles; parents; youth sexuality; premarital sex; teenage pregnancy; adolescent sexual and reproductive behavior. Introduction This research sought to present a more comprehensive look at teenage reproductive and sexual behaviours and how these behaviours are likely to be influenced by parenting styles of primary caregivers of adolescents in Suhum, in Eastern Ghana. The study aimed to identify risky sexual and reproductive behaviours and their underlying factors among in- school and out-of-school adolescents and how parenting styles might play a role. It was hypothesized that a balance of parenting styles is more likely to 1 Acknowledgements: I owe debts of gratitude to Ms. -

Ghana Poverty Mapping Report

ii Copyright © 2015 Ghana Statistical Service iii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Ghana Statistical Service wishes to acknowledge the contribution of the Government of Ghana, the UK Department for International Development (UK-DFID) and the World Bank through the provision of both technical and financial support towards the successful implementation of the Poverty Mapping Project using the Small Area Estimation Method. The Service also acknowledges the invaluable contributions of Dhiraj Sharma, Vasco Molini and Nobuo Yoshida (all consultants from the World Bank), Baah Wadieh, Anthony Amuzu, Sylvester Gyamfi, Abena Osei-Akoto, Jacqueline Anum, Samilia Mintah, Yaw Misefa, Appiah Kusi-Boateng, Anthony Krakah, Rosalind Quartey, Francis Bright Mensah, Omar Seidu, Ernest Enyan, Augusta Okantey and Hanna Frempong Konadu, all of the Statistical Service who worked tirelessly with the consultants to produce this report under the overall guidance and supervision of Dr. Philomena Nyarko, the Government Statistician. Dr. Philomena Nyarko Government Statistician iv TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ............................................................................. iv LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ -

3. Acheampong 2910

Peer-Reviewed Article Volume 10, Issue SI (2021), pp. 39-56 Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education Special Issue: Schooling & Education in Ghana ISSN: 2166-2681Print 2690-0408 Online https://ojed.org/jise Promoting Assessment for Learning to Ensure Access, Equity, and Improvement in Educational Outcomes in Ghana Eugene Owusu-Acheampong Cape Coast Technical University, Ghana Olivia A. T. Frimpong Kwapong University of Ghana, Ghana ABSTRACT This study looked at assessment for learning as a criterion for promoting inclusiveness and equitable access to educational opportunities in Ghana. It compared assessment for learning and assessment of learning and recommended measures to evaluate students’ performance to allow for equitable access and progression in education. The study found the deployment of assessment of learning as discriminatory, restrictive, and ineffective for judging the overall worth of students after several years of learning. It is recommended that to ensure equitable access and fairness such that no child is left behind in the Ghanaian educational system, the criteria for progression of students be based on interest and academic strengths using assessment for learning approaches and not necessarily standardized tests. Keywords: access, assessment of learning, assessment for learning, educational outcomes, equity, formative, summative - 37 - INTRODUCTION Education is key to development. The heart of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which was adopted by the Member States of the United Nations in the year 2015, was the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. The fourth goal focuses on quality education (UN, n.d.). As noted by Kopnina (2020), the SDG Goal 4 on quality education expects all learners to acquire the knowledge and skills that are required for sustainable development. -

(SHS) and Quality University Education in Ghana: the Role of the University Teacher

E-ISSN 2240-0524 Journal of Educational and Social Research Vol 10 No 5 ISSN 2239-978X www.richtmann.org September 2020 . Research Article © 2020 Adu-Gyamfi et.al.. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) Free Senior High School (SHS) and Quality University Education in Ghana: The Role of the University Teacher Samuel Adu-Gyamfi1 Charles Ofosu Marfo2 Ali Yakubu Nyaaba1 Kwasi Amakye-Boateng1 Mohammed Abass1 Henry Tettey Yartey1 1Department of History and Political Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana 2Department of Language and Communication Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana DOI: https://doi.org/10.36941/jesr-2020-0101 Abstract Ghana’s education system has gone through several reforms in the post-independence period in the bid to increase access, ensure equity and quality at all levels (basic to tertiary). However, these goals seem to be a mirage especially on issues concerning quality at the secondary and tertiary levels. Against this backdrop, it has become imperative to raise relevant questions for the development of a new synthesis that is practical enough to allow for the necessary action to push forward the quality discourse which is a major concern among stakeholders. This paper intends to at least, serve the purpose of refreshing our memories concerning how we have individually or collectively, as citizens and academics, pondered over free secondary education, quality education and the role of the university teacher within the melting pot of the quality discourse in Ghana. -

Black Civilization and the Arts: African Art in Search of a New Identity

TEXT NOo COLc 1/12/GHAo8 SECOND WORLD BLACK AND AFRICAN FESTIVAL OF ARTS AND CULTURE LAGOS, NIGERIA L5 JANUARY - 12 FEBRUARY, 1977 COLLOQUIUM MAIN THEME: BLACK CIVILIZATION AND EDUCATION SUB-THEME BLACK CIVILIZATION AND THE ARTS BLACK CIVILIZATION AND THE AR. ~ AFRICAN ART IN SEARCH OF A NEW IDENTITY by So F. Galevo University of Kumasi, Ghana English original COPYRIGHT RESERVED: Not for p0blication without written permission from the author or through the International Secretariat. BLACK CIVILIZATION AND THE ARTS: AFRICAN ART IN SEARCH OF A NE\"J IDENTITY by S. F. Galevo University of Kumasi, Ghana Civilization has man i fes ted itself among Black Men in many unique ways, and Black fliiehnave influenced civili&ations all over the world and down the ages. By no means least among the elements of civilization, the arts have been perhaps the field of the Black Man·s greatest contribution to the world's cultural heritage. The authenticity of the claim laid by the Black Man to great ancient civilizations is now beyond doubt, the truth having been confirm by famous scholars, including several from a different race. Sir Arthur Evans certifies that by 500 B.C. Athens was unkno~m_ She had to wait long to receive civilization from Africa through the island of Crete. In the History of Nations (Vol.18, p s l, 1906), we read: "The African continent is no recent discovery •••••••• While yet Europe was the home of wandering barbarians one of the most wonder-ful. civilizations on record had begun to v~rk out its destiny on the banks of the Nile •••••••••••• " The argument that Egypt's ancient civilization was white has been refuted, again, by several men of knowledge of high$tanding who are not black. -

MOBA Newsletter 1 Jan-Dec 2019 1 260420 1 Bitmap.Cdr

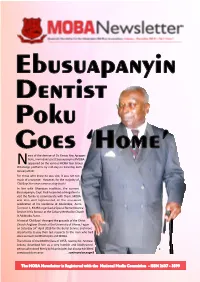

Ebusuapanyin Dentist Poku Goes ‘Home’ ews of the demise of Dr. Fancis Yaw Apiagyei Poku, immediate past Ebusuapanyin of MOBA Nappeared on the various MOBA Year Group WhatsApp plaorms by mid-day on Saturday 26th January 2019. For those who knew he was sick, it was not too much of a surprise. However, for the majority of 'Old Boys' the news came as a big shock! In line with Ghanaian tradion, the current Ebusuapanyin, Capt. Paul Forjoe led a delegaon to visit the family to commiserate with them. MOBA was also well represented at the one-week celebraon at his residence at Abelenkpe, Accra. To crown it, MOBA organised a Special Remembrance Service in his honour at the Calvary Methodist Church in Adabraka, Accra. A host of 'Old Boys' thronged the grounds of the Christ Church Anglican Church at the University of Ghana, Legon on Saturday 24th April 2019 for the Burial Service and more importantly to pay their last respects to the man who had done so much for Mfantsipim and MOBA. The tribute of the MOBA Class of 1955, read by Dr. Andrew Arkutu, described him as a very humble and kindhearted person who stood firmly by his principles but always exhibited a composed demeanor. ...connued on page 8 The MOBA Newsletter is Registered with the National Media Commision - ISSN 2637 - 3599 Inside this Issue... Comments 5 Editorial: ‘Old Boys’ - Let’s Up Our Game 6 From Ebusuapanyin’s Desk Cover Story 8. Dr. Poku Goes Home 9 MOBA Honours Dentist Poku From the School 10 - 13 News from the Hill MOBA Matters 15 MOBA Elections 16 - 17 Facelift Campaign Contributors 18 - 23 2019 MOBA Events th 144 Anniversary 24 - 27 Mfantsipim Celebrates 144th Anniversary 28 2019 SYGs Project - Staff Apartments Articles 30 - 31 Reading, O Reading! Were Art Thou Gone? 32 - 33 2019 Which Growth? Lifestyle Advertising Space Available 34 - 36 Journey from Anumle to Kotokuraba Advertising Space available for Reminiscences businesses, products, etc. -

The Educators'network 2Nd Literacy Forum

…inspiring Ghanaian teachers PRESENTS THE EDUCATORS’ NETWORK 2ND LITERACY FORUM An intensive, wide-ranging series of workshops designed for educators who are seeking to improve students’ reading and writing skills. under the theme, THE READING-WRITING CONNECTION: BOOSTING CHILDREN’S LITERACY SKILLS Saturday 24th November 2012 8:00 am – 5:30 pm at Lincoln Community School, Abelenkpe P.O. Box OS 1952, Accra Email: [email protected] …inspiring Ghanaian teachers THE PURPOSE OF THE EDUCATORS NETWORK LITERACY FORUMS Effective educators are life-long learners. Of all the factors that contribute to student learning, recent research shows that classroom instruction is the most crucial. This places teachers as the most important influence on student performance. For this reason, teachers must be given frequent opportunities to develop new instructional skills and methodologies, and share their knowledge of best practice with other teachers. It is imperative that such opportunities are provided to encourage the refining of skills, inquiry into practice and incorporation of new methods in classroom settings. To create these opportunities, The Educators’ Network (TEN) was established as a teacher initiative to provide professional development opportunities for teachers in Ghana. Through this initiative, TEN hopes to grow a professional learning community among educators in Ghana. BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE EDUCATORS’ NETWORK TEN was founded by a group of Ghanaian international educators led by Letitia Naami Oddoye, who are passionate about teaching and have had the benefit of exposure to diverse educational curricula and standards. Each of these educators has over ten years of experience in teaching and exposure to international seminars and conferences. -

Kofi Annan Media Image (Mediální Obraz Kofiho Annana )

UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE FAKULTA HUMANITNÍCH STUDIÍ Katedra elektronické kultury a sémiotiky Nathan Wesley Kofi Annan Media Image (Mediální obraz Kofiho Annana ) Diplomová práce Studijní program: Mediální a komunika ční studia (7202T) Studijní obor: Elektronická kultura a sémiotika Vedoucí práce: Prof. PhDr. Miroslav Marcelli, Ph.D. Praha 2009 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem p ředkládanou práci zpracoval samostatn ě a použil jen uvedené prameny a literaturu. Sou časn ě dávám svolení k tomu, aby tato práce byla zp řístupn ěna v příslušné knihovn ě UK a prost řednictvím elektronické databáze vysokoškolských kvalifika čních prací v repozitá ři Univerzity Karlovy a používána ke studijním ú čel ům v souladu s autorským právem. V Praze dne 14. ledna 2008 Nathan Wesley SUMMARY ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................1 1. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................2 2. THESIS AND METHOD OF RESEARCH.....................................................4 3. THE UNITED NATIONS ORGANIZATION ................................................6 4. THE UN SECRETARY GENERAL ...............................................................8 4.1. KOFI ANNAN .........................................................................................9 5. MEDIA THEORY..........................................................................................12 5.1. BARTHES MYTHOLOGIES................................................................12