Peer Gynt, Or the Difficulty of Becoming a Poet in Norway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Licensing Agency - NLA

Newspaper Licensing Agency - NLA Publisher/RRO Title Title code Ad Sales Newquay Voice NV Ad Sales St Austell Voice SAV Ad Sales www.newquayvoice.co.uk WEBNV Ad Sales www.staustellvoice.co.uk WEBSAV Advanced Media Solutions WWW.OILPRICE.COM WEBADMSOILP AJ Bell Media Limited www.sharesmagazine.co.uk WEBAJBSHAR Alliance News Alliance News Corporate ALLNANC Alpha Newspapers Antrim Guardian AG Alpha Newspapers Ballycastle Chronicle BCH Alpha Newspapers Ballymoney Chronicle BLCH Alpha Newspapers Ballymena Guardian BLGU Alpha Newspapers Coleraine Chronicle CCH Alpha Newspapers Coleraine Northern Constitution CNC Alpha Newspapers Countydown Outlook CO Alpha Newspapers Limavady Chronicle LIC Alpha Newspapers Limavady Northern Constitution LNC Alpha Newspapers Magherafelt Northern Constitution MNC Alpha Newspapers Newry Democrat ND Alpha Newspapers Strabane Weekly News SWN Alpha Newspapers Tyrone Constitution TYC Alpha Newspapers Tyrone Courier TYCO Alpha Newspapers Ulster Gazette ULG Alpha Newspapers www.antrimguardian.co.uk WEBAG Alpha Newspapers ballycastle.thechronicle.uk.com WEBBCH Alpha Newspapers ballymoney.thechronicle.uk.com WEBBLCH Alpha Newspapers www.ballymenaguardian.co.uk WEBBLGU Alpha Newspapers coleraine.thechronicle.uk.com WEBCCHR Alpha Newspapers coleraine.northernconstitution.co.uk WEBCNC Alpha Newspapers limavady.thechronicle.uk.com WEBLIC Alpha Newspapers limavady.northernconstitution.co.uk WEBLNC Alpha Newspapers www.newrydemocrat.com WEBND Alpha Newspapers www.outlooknews.co.uk WEBON Alpha Newspapers www.strabaneweekly.co.uk -

FORUM Connemara CLG End of Year Report 2018

FORUM Connemara CLG End of Year Report 2018 1 FORUM CONNEMARA CLG END OF YEAR REPORT January –December 2018. Introduction From January December 2018, Forum staff implemented actions under a number of programmes; The Rural Development Programme (Leader), The Adolescent Support Programme, the Rural Recreation Programme (RRP), the Rural Social Scheme, and Labour Activation Programmes Tus, Job Initiative, and Community Employment. There were difficulties in filling Tus places and in April the Department proposed a cutback to our allocation from 80 to 40 places. Forum meet with the Department in October .The Department confirmed our allocation of 40 places on Tus and 36 on RSS .The company lost two TUS supervisors but gained an additional supervisor for the RSS programme. Forum were allocated an additional 12 places on the RSS programme. These places are filling slowly, There are currently 31 places filled with 5 places remaining to be filled .. There will be a further review of places on both schemes scheme at the end of April 2019. During the year various staff gave comprehensive presentations on their work to the Board of Directors. This included work undertaken by the Rural Recreation Officer and the Adolescent Support Coordinator. The Adolescent Support Programme had a very successful 20th birthday celebration in May and there was also a presentation of the programmes activities to the GRETB Board who part fund the programme. The company’s finances are in a healthy state as at the end of December . Minister Ring’s Mediator/Facilitator: Representatives from Forum meet with Tom Barry facilitator on Wednesday 28th March 2018. -

Clifden Local Area Plan 2018-2024 December 2018

Clifden Local Area Plan 2018-2024 December 2018 2 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 1.1 Preamble ...................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Profile of Clifden ............................................................................................................ 3 1.3 Local Area Plan ............................................................................................................. 4 1.4 Plan Informants & Key Considerations .......................................................................... 6 2.0 Strategic Vision and Development Strategy .............................................................. 9 2.1 Strategic Vision ............................................................................................................. 9 2.2 Development Strategy ................................................................................................. 14 3.0 Development Policies, Objectives and Guidelines ................................................. 14 3.1 Land Use Management ............................................................................................... 16 3.2 Residential Development ............................................................................................ 24 3.3 Social and Community Development .......................................................................... 28 3.4 Economic Development ............................................................................................. -

“Am I Not of Those Who Reared / the Banner of Old Ireland High?” Triumphalism, Nationalism and Conflicted Identities in Francis Ledwidge’S War Poetry

Romp /1 “Am I not of those who reared / The banner of old Ireland high?” Triumphalism, nationalism and conflicted identities in Francis Ledwidge’s war poetry. Bachelor Thesis Charlotte Romp Supervisor: dr. R. H. van den Beuken 15 June 2017 Engelse Taal en Cultuur Radboud University Nijmegen Romp /2 Abstract This research will answer the question: in what ways does the poetry written by Francis Ledwidge in the wake of the Easter Rising reflect a changing stance on his role as an Irish soldier in the First World War? Guy Beiner’s notion of triumphalist memory of trauma will be employed in order to analyse this. Ledwidge’s status as a war poet will also be examined by applying Terry Phillips’ definition of war poetry. By remembering the Irish soldiers who decided to fight in the First World War, new light will be shed on a period in Irish history that has hitherto been subjected to national amnesia. This will lead to more complete and inclusive Irish identities. This thesis will argue that Ledwidge’s sentiments with regards to the war changed multiple times during the last year of his life. He is, arguably, an embodiment of the conflicting loyalties and tensions in Ireland at the time of the Easter Rising. Key words: Francis Ledwidge, Easter Rising, First World War, Ireland, Triumphalism, war poetry, loss, homesickness Romp /3 Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Chapter 1 History and Theory ................................................................................................... -

YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares Beside the Edmund Dulac Memorial Stone to W

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/194 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the same series YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 1, 2 Edited by Richard J. Finneran YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 3-8, 10-11, 13 Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS AND WOMEN: YEATS ANNUAL No. 9: A Special Number Edited by Deirdre Toomey THAT ACCUSING EYE: YEATS AND HIS IRISH READERS YEATS ANNUAL No. 12: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould and Edna Longley YEATS AND THE NINETIES YEATS ANNUAL No. 14: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS’S COLLABORATIONS YEATS ANNUAL No. 15: A Special Number Edited by Wayne K. Chapman and Warwick Gould POEMS AND CONTEXTS YEATS ANNUAL No. 16: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould INFLUENCE AND CONFLUENCE: YEATS ANNUAL No. 17: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares beside the Edmund Dulac memorial stone to W. B. Yeats. Roquebrune Cemetery, France, 1986. Private Collection. THE LIVING STREAM ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF A. NORMAN JEFFARES YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 A Special Issue Edited by Warwick Gould http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Gould, et al. (contributors retain copyright of their work). The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text. -

John L. Burke Papers

Leabharlann Naisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 63 JOHN L. BURKE PAPERS (Mss 34,246-34,249; 36,100-36,125) ACC. Nos. 4829, 5135, 5258, 5305 INTRODUCTION The papers of John Leo Burke (1888-1959) were donated to the National Library of Ireland by his daughter Miss Ann Burke. The major part of this Collection was received in two sections in September 1997 and January 2000 (Accession 5135). Other material was donated as follows: September 1994 (Accession 4829); June 1998 (Accession 5258) and November 1998 (Accession 5305). These various accruals have been consolidated in this List. The Collection also includes a biographical note on John Leo Burke by Robert Tracy (MS 36,125(4)). LETTERS TO JOHN L. BURKE MS 36,100(1) Actors’ Church Union. Irish Branch 1953 Oct.: Circular in support of the Irish Branch. Autograph signature of Lennox Robinson. 1 printed item. MS 36,100(2) Allgood, Sara 1923 Dec. 12: Thanking JLB for sending story; Abbey production of T.C. Murray’s Birthright. 1 sheet + cover. MS 36,100(3) Bodkin, Thomas 1959 June 16: Gift of print for John Costello. Portrait of Joyce. Unhappy about conditions at National Gallery – “God save us all from the machinations of incompetence.” 1 sheet. MS 36,100(4) Colum, Padraic 1949 Sept. 6: Thanking JLB for photograph of Joyce. Good quality of articles in The Shanachie. “Joyce used to frequent Aux Trianons, opposite Gare Montparnasse. The food is good …”. 1 sheet + cover. MS 36,100(5-6) Cosgrave, W. T. 2 items: Undated: Christmas card. -

National Library of Ireland

ABOUT TOWN (DUNGANNON) AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) No. 1, May - Dec. 1986 Feb. 1950- April 1951 Jan. - June; Aug - Dec. 1987 Continued as Jan.. - Sept; Nov. - Dec. 1988 AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Jan. - Aug; Oct. 1989 May 1951 - Dec. 1971 Jan, Apr. 1990 April 1972 - April 1975 All Hardcopy All Hardcopy Misc. Newspapers 1982 - 1991 A - B IL B 94109 ADVERTISER (WATERFORD) AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Mar. 11 - Sept. 16, 1848 - Microfilm See AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) ADVERTISER & WATERFORD MARKET NOTE ALLNUTT'S IRISH LAND SCHEDULE (WATERFORD) (DUBLIN) March 4 - April 15, 1843 - Microfilm No. 9 Jan. 1, 1851 Bound with NATIONAL ADVERTISER Hardcopy ADVERTISER FOR THE COUNTIES OF LOUTH, MEATH, DUBLIN, MONAGHAN, CAVAN (DROGHEDA) AMÁRACH (DUBLIN) Mar. 1896 - 1908 1956 – 1961; - Microfilm Continued as 1962 – 1966 Hardcopy O.S.S. DROGHEDA ADVERTISER (DROGHEDA) 1967 - May 13, 1977 - Microfilm 1909 - 1926 - Microfilm Sept. 1980 – 1981 - Microfilm Aug. 1927 – 1928 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1982 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1929 - Microfilm 1983 - Microfilm Incorporated with DROGHEDA ARGUS (21 Dec 1929) which See. - Microfilm ANDERSONSTOWN NEWS (ANDERSONSTOWN) Nov. 22, 1972 – 1993 Hardcopy O.S.S. ADVOCATE (DUBLIN) 1994 – to date - Microfilm April 14, 1940 - March 22, 1970 (Misc. Issues) Hardcopy O.S.S. ANGLO CELT (CAVAN) Feb. 6, 1846 - April 29, 1858 ADVOCATE (NEW YORK) Dec. 10, 1864 - Nov. 8, 1873 Sept. 23, 1939 - Dec. 25th, 1954 Jan. 10, 1885 - Dec. 25, 1886 Aug. 17, 1957 - Jan. 11, 1958 Jan. 7, 1887 - to date Hardcopy O.S.S. (Number 5) All Microfilm ADVOCATE OR INDUSTRIAL JOURNAL ANOIS (DUBLIN) (DUBLIN) Sept. 2, 1984 - June 22, 1996 - Microfilm Oct. 28, 1848 - Jan 1860 - Microfilm ANTI-IMPERIALIST (DUBLIN) AEGIS (CASTLEBAR) Samhain 1926 June 23, 1841 - Nov. -

NOEA Yearbook2018

CREATE / COLLABORATE / CONTROL 2019 YEARBOOK CELEBRATING 40 YEARS National Outdoor Events Association AS THE UK’S LEADING OUTDOOR TRADE www.noea.org.uk ASSOCIATION NATIONAL OUTDOOR EVENTS ASSOCIATION 2019 YEARBOOK 3 CONTENTS An Introduction to the National Outdoor Events Association 5 Code of Professional Practice | Legal AdVice | Insurance Panel 6 Message from the President and Vice President 8-9 UniVersitY of DerbY – Event SafetY Diploma 9 NOEA – Values and Goals 10-11 CEO’s Report 12 NOEA Scotland 13 General Council Members 2018/2019 Picture GallerY 14 General Council Members 2018/2019 Contact Details 15 NeW Council Members 16 Events IndustrY Forum 17 So Where Did It Go Wrong – A Suppliers PerspectiVe 18 40th AnniVersarY of NOEA 18-19 Business Visits & Events Partnership Working With VisitBritain 20 Special Memberships and Affiliations 21 Event Solutions NOEA 16th Annual Convention and AWards Dinner 21 2018 AWard Winners Pictures 22 Judges for the AWards 23 NOEA 2018 AWard Winners 24-25 Recording Breaking Convention 25 NOEA AWard Sponsors Logos 25 Futures Sponsors 26 AWards Sponsors 27-28 Media Partner 28 2Can Productions Members NeWs 29-38 Front cover photographs: Annual Convention and AWards Dinner Packages 42-43 Stage Lighting SerVices, Tintern AbbeY List of NOEA Members – Full details 44-67 Bournemouth 7s, SomersbY Cider Garden Classified Headings IndeX 68-76 We Are the Fair, El Dorado FestiVal Richmond Event Management Ltd, The opinions expressed by contributors to this publication are not Bristol Balloon Fiesta always a reflection of the opinions or the policy of the Association National Outdoor Events Association, PO BoX 4495, Wells BA5 9AS Tel. -

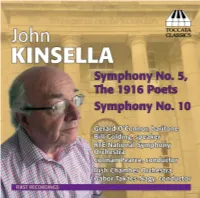

Toccata Classics TOCC0242 Notes

Americas, and from further aield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, JOHN KINSELLA, IRISH SYMPHONIST by Séamas da Barra John Kinsella was born in Dublin on 8 April 1932. His early studies at the Dublin College of Music were devoted to the viola as well as to harmony and counterpoint, but he is essentially self-taught as a composer. He started writing music as a teenager and although he initially adopted a straightforward, even conventional, tonal idiom, he began to take a serious interest in the compositional techniques of the European avant-garde from the early 1960s. He embraced serialism in particular as a liberating influence on his creative imagination, and he produced a substantial body of work during this period that quickly established him in Ireland as one of the most interesting younger figures of the day. In 1968 Kinsella was appointed Senior Assistant in the music department of Raidió Teilefís Éireann (RTÉ), the Irish national broadcasting authority, a position that allowed him to become widely acquainted with the latest developments in contemporary music, particularly through the International Rostrum of Composers organised under the auspices of UNESCO. But much of what he heard at these events began to strike him as dispiritingly similar in content, and he was increasingly persuaded that for many of his contemporaries conformity with current trends had become more P important than a desire to create out of inner conviction. As he found himself growing disillusioned with the avant-garde, his attitude to his own work began to change and he came to question the artistic validity of much of what he had written. -

Terror Fried Brains

wake up! wake up! it’s yer sunny side up Summer Solstice 2003 Free/Donation Issue 411/412 TERROR FRIED BRAINS “Every ten years or so, the United States Poached Rights needs to pick up some small crappy little Switch on the news and you hear about CRAP ARREST OF THE WEEK country and throw it against the wall, just to more terrorists being arrested. But who For reading the paper! show the world we mean business.”-Michael are they? In December, five Turks and a An American anti-war prisoner serving time Ledden, holder of the ‘Freedom Chair’ at Briton were charged under the Terrorism for protesting at a military base was put the American Enterprise Institute. Act 2000 for supporting the Turkish into solitary confinement for eight days af- Last week a poll revealed that a third Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party- ter he got sent and distributed anti-war ar- of Americans believe that weapons of mass Front, or DHKP-C. They were nicked be- ticles from such radical publications as the destruction have been found in Iraq, while New York Times, Readers’ Digest, cause DHKP-C has been banned by the Newsweek, and The Guardian! Better not 22 per cent reckon Iraq actually used UK government and the six arrestees were send him this weeks SchNEWS then. them! Even before the war, half of those supposedly “facilitating the retention or www.naplesnews.com/03/06/florida/ polled said the Iraq regime was responsi- control of terrorist property.” Guns? d939395a.htm ble for September 11th. But no one’s found Bombs? Er, no, the people arrested were any weapons of mass destruction let alone simply in possession of magazines, vid- handcuffed at gunpoint and driven to Govan used them (well apart from the Americans eos and posters that supported the Police Station. -

'Offensive and Riotous Behaviour'? Performing the Role of an Audience

‘Offensive and Riotous Behaviour’? Performing the Role of an Audience in Irish Cinema of the mid-1910s Denis Condon, Nation University of Ireland Maynooth In September 1915, Frederick Arthur Sparling, proprietor of the Bohemian Picture Theatre, Dublin, prosecuted William Larkin on a charge of offensive and riotous behaviour for protesting in the auditorium during a screening of A Modern Magdalen (US: Life Photo Film, 1915). The protest was part of an ongoing campaign by the Catholic church-based vigilance committees – led by the Dublin Vigilance Committee (DVC) – against certain kinds of imported popular culture, initially targeting newspapers, magazines and books and moving on by 1915 to theatrical shows and films.1 Larkin played a leading role in the confrontational elements of the campaign, gaining notoriety among theatre and cinema owners as he successfully drew press attention to the DVC’s activities. Newspaper accounts of this case stand out in early Irish cinema history as providing the most extensive evidence of audience behaviour, but they also pose methodological questions. These include what the most appropriate way is to discuss Larkin’s protest, which was not “normal” behaviour but a kind of spectacular performance – honed and rehearsed – whose rhetorical intent was to suggest that he spoke for a silent majority too timid to voice their own interpretation of unacceptable images. Accounts of this case suggest that Larkin and the DVC rejected the attentive passivity apparently demanded of cinema audiences by such factors as the feature film’s growing dominance on the cinema programme in order to provide a space for performances of a Catholic Irishness they thought inadequately – or sometimes insultingly – portrayed on screen. -

" class="text-overflow-clamp2"> Barronstrand Street,;' U • ¦ I Respectable "" >

' \ , ¦:¦ I ; i: I -j^LO - \ 1 ¦ - ¦ -:J ' . 4. ¦¦ ¦ '¦'I ' - ' ¦a.v - ;¦ V • ' if- ^/' . , ., ; • '¦ - " ' . jgr . ;r pa j j M S , • j . ^ ¦: I ; ^ I . /£&*&$&: on¦ij jBedsijeadls ! ~ ~~n~~r c% ^ BdrronstrandM ' X , Perambulators ! T' - , . #iBMHED ! IN ! l848 ?J7 DB O VOL. ikni i Na 3,408 MAY , j FKIDA^.; 20, BEaiBTEBED AT THE GENERAL 'U _-i_L__L 1914. POST¦ OFnOE A8 A NEW8PAPEB. ; 1 ONE ! - : i : ; " - ¦ • ¦ i ii i TT - if i • ' ¦ • I- ¦ P^IC| PEJJNY ;] ¦ ' . :' - |i ; r- • - "-" ¦ ¦¦ -!' -V\ I . ¦ • . : nipmna Son\pariie5 B«nks Iddtl Offices, et || jc«D«iii^wi|8ements public : ^.nnouneements. ¦ LW , , . ¦ ¦ ¦ — — Clyde] p . i i i . ;. , ^r . .- : . —rr Ship ing! Company, ! :; j! ! . 1 Im^ortaiit to Farmers 3 pqXTJiACtS -^OB OOAlis iFX»B .HB3£¦ • •• .ad Powerful ¦tjtuaniert. ' Excellent Passenger Accommodation.' Electric Light. ^c ^ Orti ^rl^^^ ' ¦ ' ' i ^™! " PEISOJSS;' ! | | Steward* and Stewardesses carried. j I V . .J j. isies . • . Reel and CHEAPEST KOUTE (nil ' , CMHO and LWa 8tock,to mdjfxom. all part* ol •; WEB QW^EMJ SRJ8ONBBOARD -will •tWjfcAND, SCOTLAND, arid N((!UTH OF JBELAIJD; buBLlSs, and OQBK. i THE CITY AND leoeive'i Beiled Teodera up to 13 o't«k ¦ : I couNmy IJOAN- co. LIMITEI); noon on SATPiaxA !l ; ! I 1 : "~ / i Y; «th?JitJ^B;I Sl^tot ; the supply o< : - ¦' >¦- ; ' - INTENDED 8AILINO8 FROM INTENDED BAttiNGB TO O'CON: il^Sf^rc^" 1 -¦ . ' HOUSE JLJJD 8SEA3I OCULS \ WASEBVOHD. ; ;. WATEEFOBD. {or ^•ke Ojuh AdT«nc<a: ¦ the aeveral Jrish.( Hriaoos durioc"> * ¦ ¦dil j to L»diw, Gen " i K !:. I ; t^meo, F«rm^m. Shopkeeper *! if'/ year endinr30th, Jane, 1SQ6.; ! , - : To LI VEBPOOL—Every j Monday, V.cd- F om LIVERPOOlr-iEiery Mi.r.dayi ^ \jig&^ ; .