Water Resources Allocation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SLIDES: Water Allocation and Water Markets in Spain

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Coping with Water Scarcity in River Basins Worldwide: Lessons Learned from Shared Experiences (Martz Summer Conference, June 2016 9-10) 6-10-2016 SLIDES: Water Allocation and Water Markets in Spain Nuria Hernández-Mora Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/coping-with-water-scarcity-in-river- basins-worldwide Part of the Climate Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Environmental Health and Protection Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Hydrology Commons, International Law Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Social Policy Commons, Sustainability Commons, Transnational Law Commons, Water Law Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Citation Information Hernández-Mora, Nuria, "SLIDES: Water Allocation and Water Markets in Spain" (2016). Coping with Water Scarcity in River Basins Worldwide: Lessons Learned from Shared Experiences (Martz Summer Conference, June 9-10). https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/coping-with-water-scarcity-in-river-basins-worldwide/23 Reproduced with permission of the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment (formerly the Natural Resources Law Center) at the University of Colorado Law School. 2016 Clyde Martz Summer Conference Boulder, Colorado, June 9-10, 2016 Water allocation and water markets in Spain Nuria Hernández- Mora, Universidad de Sevilla SPAIN Outline 1. Context 2. Triggers, characteristics and -

Evaluating Vapor Intrusion Pathways

Evaluating Vapor Intrusion Pathways Guidance for ATSDR’s Division of Community Health Investigations October 31, 2016 Contents Acronym List ........................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................... 2 What are the potential health risks from the vapor intrusion pathway? ............................................................................... 2 When should a vapor intrusion pathway be evaluated? ........................................................................................................ 3 Why is it so difficult to assess the public health hazard posed by the vapor intrusion pathway? .......................................... 3 What is the best approach for a public health evaluation of the vapor intrusion pathway? ................................................. 5 Public health evaluation.......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Vapor intrusion evaluation process outline ............................................................................................................................ 8 References… …...................................................................................................................................................................... -

National Primary Drinking Water Regulations

National Primary Drinking Water Regulations Potential health effects MCL or TT1 Common sources of contaminant in Public Health Contaminant from long-term3 exposure (mg/L)2 drinking water Goal (mg/L)2 above the MCL Nervous system or blood Added to water during sewage/ Acrylamide TT4 problems; increased risk of cancer wastewater treatment zero Eye, liver, kidney, or spleen Runoff from herbicide used on row Alachlor 0.002 problems; anemia; increased risk crops zero of cancer Erosion of natural deposits of certain 15 picocuries Alpha/photon minerals that are radioactive and per Liter Increased risk of cancer emitters may emit a form of radiation known zero (pCi/L) as alpha radiation Discharge from petroleum refineries; Increase in blood cholesterol; Antimony 0.006 fire retardants; ceramics; electronics; decrease in blood sugar 0.006 solder Skin damage or problems with Erosion of natural deposits; runoff Arsenic 0.010 circulatory systems, and may have from orchards; runoff from glass & 0 increased risk of getting cancer electronics production wastes Asbestos 7 million Increased risk of developing Decay of asbestos cement in water (fibers >10 fibers per Liter benign intestinal polyps mains; erosion of natural deposits 7 MFL micrometers) (MFL) Cardiovascular system or Runoff from herbicide used on row Atrazine 0.003 reproductive problems crops 0.003 Discharge of drilling wastes; discharge Barium 2 Increase in blood pressure from metal refineries; erosion 2 of natural deposits Anemia; decrease in blood Discharge from factories; leaching Benzene -

Freshwater Resources and Their Management

3 Freshwater resources and their management Coordinating Lead Authors: Zbigniew W. Kundzewicz (Poland), Luis José Mata (Venezuela) Lead Authors: Nigel Arnell (UK), Petra Döll (Germany), Pavel Kabat (The Netherlands), Blanca Jiménez (Mexico), Kathleen Miller (USA), Taikan Oki (Japan), Zekai Senç (Turkey), Igor Shiklomanov (Russia) Contributing Authors: Jun Asanuma (Japan), Richard Betts (UK), Stewart Cohen (Canada), Christopher Milly (USA), Mark Nearing (USA), Christel Prudhomme (UK), Roger Pulwarty (Trinidad and Tobago), Roland Schulze (South Africa), Renoj Thayyen (India), Nick van de Giesen (The Netherlands), Henk van Schaik (The Netherlands), Tom Wilbanks (USA), Robert Wilby (UK) Review Editors: Alfred Becker (Germany), James Bruce (Canada) This chapter should be cited as: Kundzewicz, Z.W., L.J. Mata, N.W. Arnell, P. Döll, P. Kabat, B. Jiménez, K.A. Miller, T. Oki, Z. Senç and I.A. Shiklomanov, 2007: Freshwater resources and their management. Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 173-210. Freshwater resources and their management Chapter 3 Table of Contents .....................................................175 3.5.2 How will climate change affect flood Executive summary damages?...............................................................196 .......................................................175 -

Water Quality Conditions in the United States a Profile from the 1998 National Water Quality Inventory Report to Congress

United States Office of Water (4503F) EPA841-F-00-006 Environmental Protection Washington, DC 20460 June 2000 Agency Water Quality Conditions in the United States A Profile from the 1998 National Water Quality Inventory Report to Congress States, tribes, territories, and interstate commissions report that, in 1998, about 40% of U.S. streams, lakes, and estuaries that were assessed were not clean enough to support uses such as fishing and swimming. About 32% of U.S. waters were assessed for this national inventory of water quality. Leading pollutants in impaired waters include siltation, bacteria, nutrients, and metals. Runoff from agricultural lands and urban areas are the primary sources of these pollu- tants. Although the United States has made significant progress in cleaning up polluted waters over the past 30 years, much remains to be done to restore and protect the nation’s waters. Findings States also found that 96% of assessed Great Lakes shoreline miles are impaired, primarily due to pollut- Recent water quality data find that more than ants in fish tissue at levels that exceed standards to 291,000 miles of assessed rivers and streams do not protect human health. States assessed 90% of Great meet water quality standards. Across all types of water- Lakes shoreline miles. bodies, states, territories, tribes, and other jurisdictions report that poor water quality affects aquatic life, fish Wetlands are being lost in the contiguous United consumption, swimming, and drinking water. In their States at a rate of about 100,000 acres per year. Eleven 1998 reports, states assessed 840,000 miles of rivers states and tribes listed sources of recent wetland loss; and 17.4 million acres of lakes, including 150,000 conversion for agricultural uses, road construction, and more river miles and 600,000 more lake acres than residential development are leading reasons for loss. -

2021 Water Quality Report

2021 WATER QUALITY REPORT 2021 WATER QUALITY REPORT CITY OF NEWARK: SOUTH WELL FIELD TREATMENT PLANT AIR STRIPPER BUILDING Annual Water Quality Report The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Newark meets or exceeds the water quality requires public water suppliers to provide standards of the Delaware Division of Public consumer confidence reports (CCR) to their Health Office of Drinking Water and the customers . These reports are also known as Environmental Protection Agency. The tables on annual water quality reports. The below report pages 4-6 of this report list those substances summarizes information regarding the sources found in our finished water during calendar year used (i.e. rivers, reservoirs, or aquifers), any 2020. detected contaminants, compliance and educational efforts. How the Water is Treated The City’s 317 million gallon reservoir provides a Drinking water, including bottled water, may At the Curtis Water Treatment Plant (CWTP), reliable source of raw water which can be treated reasonably be expected to contain at least small water from the White Clay Creek is clarified with and ready for drinking in times of heavy rain or amounts of some substances. The presence of alum and polymer and then filtered to remove drought. In an effort to keep sediment these substances does not necessarily indicate impurities. Chlorine is added to kill harmful accumulation in our water mains to a minimum, that water poses a health risk. In order to ensure bacteria and viruses. Finally, fluoride is added to we flush the entire system yearly. that tap water is safe to drink, the EPA prescribes the water to protect your teeth. -

Groundwater Overdraft, Electricity, and Wrong Incentives : Evidence from Mexico

Groundwater Overdraft, Electricity, and Wrong Incentives : Evidence from Mexico Vincente Ruiz WP 2016.05 Suggested citation: V. Ruiz (2016). Groundwater Overdraft, Electricity, and Wrong Incentives : Evidence from Mexico. FAERE Working Paper, 2016.05. ISSN number: 2274-5556 www.faere.fr Groundwater Overdraft, Electricity, and Wrong Incentives: Evidence from Mexico by Vicente Ruiz⇤ Last version: January 2016 Abstract Groundwater overdraft is threatening the sustainability of an increasing number of aquifers in Mexico. The excessive amount of groundwater ex- tracted by irrigation farming has significantly contributed to this problem. The objective of this paper is to analyse the effect of changes in ground- water price over the allocation of different production inputs. I model the technology of producers facing groundwater overdraft through a Translog cost function and using a combination of multiple micro-data sources. My results show that groundwater demand is inelastic, -0.54. Moreover, these results also show that both labour and fertiliser can act as substitutes for groundwater, further reacting to changes in groundwater price. JEL codes:Q12,Q25 Key words: Groundwater, Electricity, Subsidies, Mexico, Translog Cost ⇤Université Paris 1 - Panthéon Sorbonne, Paris School of Economics (PSE). Centre d’Économie de la Sorbonne, 106-112 Boulevard de l’Hopital, 75647, Paris Cedex 13, France. Email: [email protected] Introduction The high rate of groundwater extraction in Mexico is threatening the sustainability of an increasing number of aquifers in the country. Today in Mexico 1 out of 6aquifersisconsideredtobeoverexploited(CONAGUA, 2010). Groundwater overdraft is not only an important cause of major environmental problems, but it also has a direct impact on economic activities and the wellbeing of a high share of the population. -

Effectiveness of Virginia's Water Resource Planning and Management

Commonwealth of Virginia House Document 8 (2017) October 2016 Report to the Governor and the General Assembly of Virginia Effectiveness of Virginia’s Water Resource Planning and Management 2016 JOINT LEGISLATIVE AUDIT AND REVIEW COMMISSION Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission Chair Delegate Robert D. Orrock, Sr. Vice-Chair Senator Thomas K. Norment, Jr. Delegate David B. Albo Delegate M. Kirkland Cox Senator Emmett W. Hanger, Jr. Senator Janet D. Howell Delegate S. Chris Jones Delegate R. Steven Landes Delegate James P. Massie III Senator Ryan T. McDougle Delegate John M. O’Bannon III Delegate Kenneth R. Plum Senator Frank M. Ruff, Jr. Delegate Lionell Spruill, Sr. Martha S. Mavredes, Auditor of Public Accounts Director Hal E. Greer JLARC staff for this report Justin Brown, Senior Associate Director Jamie Bitz, Project Leader Susan Bond Joe McMahon Christine Wolfe Information graphics: Nathan Skreslet JLARC Report 486 ©2016 Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission http://jlarc.virginia.gov February 8, 2017 The Honorable Robert D. Orrock Sr., Chair Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission General Assembly Building Richmond, Virginia 23219 Dear Delegate Orrock: In 2015, the General Assembly directed the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) to study water resource planning and management in Virginia (HJR 623 and SJR 272). As part of this study, the report, Effectiveness of Virginia’s Water Resource Planning and Management, was briefed to the Commission and authorized for printing on October 11, 2016. On behalf of Commission staff, I would like to express appreciation for the cooperation and assistance of the staff of the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality and the Virginia Water Resource Research Center at Virginia Tech. -

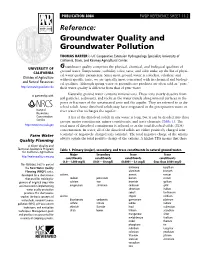

Reference: Groundwater Quality and Groundwater Pollution

PUBLICATION 8084 FWQP REFERENCE SHEET 11.2 Reference: Groundwater Quality and Groundwater Pollution THOMAS HARTER is UC Cooperative Extension Hydrogeology Specialist, University of California, Davis, and Kearney Agricultural Center. roundwater quality comprises the physical, chemical, and biological qualities of UNIVERSITY OF G ground water. Temperature, turbidity, color, taste, and odor make up the list of physi- CALIFORNIA cal water quality parameters. Since most ground water is colorless, odorless, and Division of Agriculture without specific taste, we are typically most concerned with its chemical and biologi- and Natural Resources cal qualities. Although spring water or groundwater products are often sold as “pure,” http://anrcatalog.ucdavis.edu their water quality is different from that of pure water. In partnership with Naturally, ground water contains mineral ions. These ions slowly dissolve from soil particles, sediments, and rocks as the water travels along mineral surfaces in the pores or fractures of the unsaturated zone and the aquifer. They are referred to as dis- solved solids. Some dissolved solids may have originated in the precipitation water or river water that recharges the aquifer. A list of the dissolved solids in any water is long, but it can be divided into three groups: major constituents, minor constituents, and trace elements (Table 1). The http://www.nrcs.usda.gov total mass of dissolved constituents is referred to as the total dissolved solids (TDS) concentration. In water, all of the dissolved solids are either positively charged ions Farm Water (cations) or negatively charged ions (anions). The total negative charge of the anions always equals the total positive charge of the cations. -

Essays on Common-Pool Resources: Evaluation of Water Management and Conservation Programs Kuatbay K

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2017 Essays on Common-Pool Resources: Evaluation of Water Management and Conservation Programs Kuatbay K. Bektemirov University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Public Policy Commons, Sustainability Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Bektemirov, Kuatbay K., "Essays on Common-Pool Resources: Evaluation of Water Management and Conservation Programs" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 2432. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Essays on Common-Pool Resources: Evaluation of Water Management and Conservation Programs A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Policy by Kuatbay Bektemirov Tashkent Automobile and Roads Institute Engineering Specialist, 1985 Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Institute of Economics Candidate of Science in Economics, 1992 Indiana University-Bloomington Master of Public Affairs, 2004 National University of Uzbekistan Doctor of Science in Economics, 2008 August 2017 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. _____________________________________ Dr. Eric Wailes Dissertation Director _____________________________________ __________________________________ Dr. Kent Kovacs Dr. Brinck Kerr Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This dissertation is comprised of three essays that examine water management and conservation programs through the context of sustainable development. -

Water Wars: the Brahmaputra River and Sino-Indian Relations

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons CIWAG Case Studies 10-2013 Water Wars: The Brahmaputra River and Sino-Indian Relations Mark Christopher Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/ciwag-case-studies Recommended Citation Christopher, Mark, "MIWS_07 - Water Wars: The Brahmaputra River and Sino-Indian Relations" (2013). CIWAG Case Studies. 7. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/ciwag-case-studies/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in CIWAG Case Studies by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Draft as of 121916 ARF R W ARE LA a U nd G A E R R M R I E D n o G R R E O T U N P E S C U N E IT EG ED L S OL TA R C TES NAVAL WA Water Wars: The Brahmaputra River and Sino-Indian Relations Mark Christopher United States Naval War College Newport, Rhode Island Water Wars: The Brahmaputra River and Sino-Indian Relations Mark Christopher Center on Irregular Warfare & Armed Groups (CIWAG) US Naval War College, Newport, RI [email protected] CHRISTOPHER: WATER WARS CIWAG Case Studies Bureaucracy Does Its Thing (in Afghanistan) – Todd Greentree Operationalizing Intelligence Dominance – Roy Godson An Operator’s Guide to Human Terrain Teams – Norman Nigh Organizational Learning and the Marine Corps: The Counterinsurgency Campaign in Iraq – Richard Shultz Piracy – Martin Murphy Reading the Tea Leaves: Proto-Insurgency in Honduras – John D. -

A Public Health Legal Guide to Safe Drinking Water

A Public Health Legal Guide to Safe Drinking Water Prepared by Alisha Duggal, Shannon Frede, and Taylor Kasky, student attorneys in the Public Health Law Clinic at the University of Maryland Carey School of Law, under the supervision of Professors Kathleen Hoke and William Piermattei. Generous funding provided by the Partnership for Public Health Law, comprised of the American Public Health Association, Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, National Association of County & City Health Officials, and the National Association of Local Boards of Health August 2015 THE PROBLEM: DRINKING WATER CONTAMINATION Clean drinking water is essential to public health. Contaminated water is a grave health risk and, despite great progress over the past 40 years, continues to threaten U.S. communities’ health and quality of life. Our water resources still lack basic protections, making them vulnerable to pollution from fracking, farm runoff, industrial discharges and neglected water infrastructure. In the U.S., treatment and distribution of safe drinking water has all but eliminated diseases such as cholera, typhoid fever, dysentery and hepatitis A that continue to plague many parts of the world. However, despite these successes, an estimated 19.5 million Americans fall ill each year from drinking water contaminated with parasites, bacteria or viruses. In recent years, 40 percent of the nation’s community water systems violated the Safe Drinking Water Act at least once.1 Those violations ranged from failing to maintain proper paperwork to allowing carcinogens into tap water. Approximately 23 million people received drinking water from municipal systems that violated at least one health-based standard.2 In some cases, these violations can cause sickness quickly; in others, pollutants such as inorganic toxins and heavy metals can accumulate in the body for years or decades before contributing to serious health problems.