Evaluating Residential Indoor Air Quality Concerns1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eye Protection Health Alert Final 11 25 08.Pub

HEALTH ALERT! Keeping an Eye On Eye Protection More than 2,000 workplace eye injuries occur EVERY DAY in the United States. A vast majority of employers provide eye protection at no cost to their employees, however 94% of eyewear being used by workers is not appropriate for the job being done and about 40% of the workers receive no eye safety training on where and what type of eyewear should be used. “90% of occupational eye injuries could have been prevented if the victim was wearing proper eye and face protection” (Prevent Blindness America) The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that 36,680 non-fatal work-related eye injuries occurred in private industry workplaces in 2004 at an estimated expense of $300 million in lost production time, medical expenses, and worker’s compensation costs. Fast Facts on Eye Injuries Eye Protection Safety Plan 9 69% of all reported facial injuries 9 Engineering Controls ~ Machine occurred to the eye. guarding, welding curtains, appropriate visible signage. 9 Nearly 70% of non-fatal eye injuries were caused by flying or falling objects 9 Administrative Controls ~ Prohibit access or sparks striking the eye. to work zones for non-workers and workers without proper safety equipment. 9 Males 25-44 years of age are at highest risk for eye injuries. 9 Personal Protective Equipment ~ Use of fitted, job specific, ANSI certified 9 The majority of eye injuries occur in protective eyewear and facewear. welders, cutters, solderers and braziers, followed by construction laborers. 9 Cleaning & Maintenance ~ Ensure proper cleaning of lens and face shields with appropriate materials and store properly to prevent damage. -

Water Quality Conditions in the United States a Profile from the 1998 National Water Quality Inventory Report to Congress

United States Office of Water (4503F) EPA841-F-00-006 Environmental Protection Washington, DC 20460 June 2000 Agency Water Quality Conditions in the United States A Profile from the 1998 National Water Quality Inventory Report to Congress States, tribes, territories, and interstate commissions report that, in 1998, about 40% of U.S. streams, lakes, and estuaries that were assessed were not clean enough to support uses such as fishing and swimming. About 32% of U.S. waters were assessed for this national inventory of water quality. Leading pollutants in impaired waters include siltation, bacteria, nutrients, and metals. Runoff from agricultural lands and urban areas are the primary sources of these pollu- tants. Although the United States has made significant progress in cleaning up polluted waters over the past 30 years, much remains to be done to restore and protect the nation’s waters. Findings States also found that 96% of assessed Great Lakes shoreline miles are impaired, primarily due to pollut- Recent water quality data find that more than ants in fish tissue at levels that exceed standards to 291,000 miles of assessed rivers and streams do not protect human health. States assessed 90% of Great meet water quality standards. Across all types of water- Lakes shoreline miles. bodies, states, territories, tribes, and other jurisdictions report that poor water quality affects aquatic life, fish Wetlands are being lost in the contiguous United consumption, swimming, and drinking water. In their States at a rate of about 100,000 acres per year. Eleven 1998 reports, states assessed 840,000 miles of rivers states and tribes listed sources of recent wetland loss; and 17.4 million acres of lakes, including 150,000 conversion for agricultural uses, road construction, and more river miles and 600,000 more lake acres than residential development are leading reasons for loss. -

2021 Water Quality Report

2021 WATER QUALITY REPORT 2021 WATER QUALITY REPORT CITY OF NEWARK: SOUTH WELL FIELD TREATMENT PLANT AIR STRIPPER BUILDING Annual Water Quality Report The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Newark meets or exceeds the water quality requires public water suppliers to provide standards of the Delaware Division of Public consumer confidence reports (CCR) to their Health Office of Drinking Water and the customers . These reports are also known as Environmental Protection Agency. The tables on annual water quality reports. The below report pages 4-6 of this report list those substances summarizes information regarding the sources found in our finished water during calendar year used (i.e. rivers, reservoirs, or aquifers), any 2020. detected contaminants, compliance and educational efforts. How the Water is Treated The City’s 317 million gallon reservoir provides a Drinking water, including bottled water, may At the Curtis Water Treatment Plant (CWTP), reliable source of raw water which can be treated reasonably be expected to contain at least small water from the White Clay Creek is clarified with and ready for drinking in times of heavy rain or amounts of some substances. The presence of alum and polymer and then filtered to remove drought. In an effort to keep sediment these substances does not necessarily indicate impurities. Chlorine is added to kill harmful accumulation in our water mains to a minimum, that water poses a health risk. In order to ensure bacteria and viruses. Finally, fluoride is added to we flush the entire system yearly. that tap water is safe to drink, the EPA prescribes the water to protect your teeth. -

New Information from MSA Safety Works Regarding EPA Lead Requirements for Remodelers

New Information from MSA Safety Works Regarding EPA Lead Requirements for Remodelers Safety Products for Remodelers for Lead Exposure Protection during Renovation, Repair and Painting Renovation of older structures can create hazardous lead dust and Personal Protective Equipment chips within those environments by disturbing lead-based paint. In • Eyewear (MSA recommends ANSI-compliant safety glasses or response to the need to help prevent lead poisoning, in 2008 the U.S. goggles - see below) Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a rule requiring use of • Painters’ hats lead-safe practices, as common renovation activities such as sanding, • Gloves cutting, and demolition can create serious lead exposure hazards. • Coveralls • Disposable shoe covers As of April 22, 2010, the EPA requires that contractors performing • N-100-rated disposable respirators (MSA recommends renovation activities that disturb lead-based paint in pre-1978-built P-100 rated respirators – see below) homes, child-care facilities, and schools must be certified and must follow specific work practices aimed at preventing lead contamination. The “eyewear” referred to by the EPA comprises safety glasses or Contractors must document compliance with this requirement and goggles compliant to the latest American National Standards Institute provide certification to customers when asked to do so. Z87.1 standard. If remodelers remove lead paint with chemical strippers, chemical splash goggles (ANSI-compliant goggles with Contractors performing work in homes, child-care -

Diffuse Pollution, Degraded Waters Emerging Policy Solutions

Diffuse Pollution, Degraded Waters Emerging Policy Solutions Policy HIGHLIGHTS Diffuse Pollution, Degraded Waters Emerging Policy Solutions “OECD countries have struggled to adequately address diffuse water pollution. It is much easier to regulate large, point source industrial and municipal polluters than engage with a large number of farmers and other land-users where variable factors like climate, soil and politics come into play. But the cumulative effects of diffuse water pollution can be devastating for human well-being and ecosystem health. Ultimately, they can undermine sustainable economic growth. Many countries are trying innovative policy responses with some measure of success. However, these approaches need to be replicated, adapted and massively scaled-up if they are to have an effect.” Simon Upton – OECD Environment Director POLICY H I GH LI GHT S After decades of regulation and investment to reduce point source water pollution, OECD countries still face water quality challenges (e.g. eutrophication) from diffuse agricultural and urban sources of pollution, i.e. pollution from surface runoff, soil filtration and atmospheric deposition. The relative lack of progress reflects the complexities of controlling multiple pollutants from multiple sources, their high spatial and temporal variability, the associated transactions costs, and limited political acceptability of regulatory measures. The OECD report Diffuse Pollution, Degraded Waters: Emerging Policy Solutions (OECD, 2017) outlines the water quality challenges facing OECD countries today. It presents a range of policy instruments and innovative case studies of diffuse pollution control, and concludes with an integrated policy framework to tackle this challenge. An optimal approach will likely entail a mix of policy interventions reflecting the basic OECD principles of water quality management – pollution prevention, treatment at source, the polluter pays and the beneficiary pays principles, equity, and policy coherence. -

Monitoring Water Quality & Quantity in Mining

SURFACE & GROUNDWATER / ENVIRONMENT & ECOSYSTEMS DHI SOLUTION MONITORING WATER QUALITY & QUANTITY IN MINING Environmental monitoring - tailor-made! ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING - THE KEY TO KNOWLEDGE SUMMARY Regardless of the project, monitoring is a crucial element of gaining knowledge CLIENT about environmental conditions. When it comes to monitoring water, it is essential The mining industry and associated to do this in an optimal way so as to provide only the necessary information, which companies can be used for specific actions. Too many monitoring programmes have been established with the aim to know everything, which eventually leads to enormous CHALLENGE amount of data but not knowledge. Assessment of water quality and quantity Water is linked to nearly every type of mining industry, whether as groundwater, Collect the right variables surface water coastal water, or process/wastewater and accordingly there is a Fulfill the regulations substantial need to assess water quality and quantity conditions in all phases of Ensure scientifically sound judgement of mining: exploration, operation/production and decommissioning. impacts We at DHI work with tailor-made monitoring, which enables the client to get all the SOLUTION relevant data - and only those. To provide tailor-made monitoring based on the relevant data Changes in water quality can Applying state-of-the-art technologies as lead to many types of impacts part of the monitoring and the mining industry unfortunately creates various VALUE such problems. One of the Optimisation of monitoring costs standard impacts comes from Fast delivery of data acid drainage of the mines or Easier compliance with permits the mine-tailing and has multiple impacts on not just the biology but also on water which is taken downstream for domestic or industrial use. -

Modification of the Water Quality Index (WQI)

water Review Modification of the Water Quality Index (WQI) Process for Simple Calculation Using the Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) Method: A Review Naseem Akhtar 1 , Muhammad Izzuddin Syakir Ishak 1,2,*, Mardiana Idayu Ahmad 1 , Khalid Umar 3 , Mohamad Shaiful Md Yusuff 1, Mohd Talha Anees 4, Abdul Qadir 5 and Yazan Khalaf Ali Almanasir 1 1 School of Industrial Technology, Division of Environmental Technology, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Gelugor 11800, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia; [email protected] (N.A.); [email protected] (M.I.A.); [email protected] (M.S.M.Y.); [email protected] (Y.K.A.A.) 2 Centre for Global Sustainability Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Gelugor 11800, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia 3 School of Chemical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Gelugor 11800, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia; [email protected] 4 Department of Geology, Faculty of Science, University of Malaya, Petaling Jaya 50603, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; [email protected] 5 School of Physics, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Gelugor 11800, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Human activities continue to affect our water quality; it remains a major problem world- wide (particularly concerning freshwater and human consumption). A critical water quality index Citation: Akhtar, N.; Ishak, M.I.S.; (WQI) method has been used to determine the overall water quality status of surface water and Ahmad, M.I.; Umar, K.; Md Yusuff, groundwater systems globally since the 1960s. WQI follows four steps: parameter selection, sub- M.S.; Anees, M.T.; Qadir, A.; Ali indices, establishing weights, and final index aggregation, which are addressed in this review. -

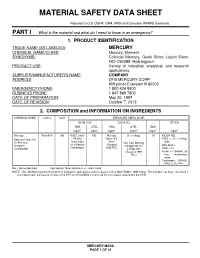

Material Safety Data Sheet

MATERIAL SAFETY DATA SHEET Prepared to U.S. OSHA, CMA, ANSI and Canadian WHMIS Standards PART I What is the material and what do I need to know in an emergency? 1. PRODUCT IDENTIFICATION TRADE NAME (AS LABELED) : MERCURY CHEMICAL NAME/CLASS : Mercury; Element SYNONYMS: Colloidal Mercury, Quick Silver; Liquid Silver; NCI-C60399; Hydrargyrum PRODUCT USE : Variety of industrial, analytical, and research applications. SUPPLIER/MANUFACTURER'S NAME : COMPANY ADDRESS : DFG MERCURY CORP 909 pitner Evanston Ill 60202 EMERGENCY PHONE : 1 800 424 9300 BUSINESS PHONE : 1 847 869 7800 DATE OF PREPARATION : May 20, 1997 DATE OF REVISION : October 7, 2013 2. COMPOSITION and INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS CHEMICAL NAME CAS # %w/w EXPOSURE LIMITS IN AIR ACGIH-TLV OSHA-PEL OTHER TWA STEL TWA STEL IDLH mg/m 3 mg/m 3 mg/m 3 mg/m 3 mg/m 3 mg/m 3 Mercury 7439-97-6 100 0.025, (skin) NE Mercury 0.1 (ceiling) 10 NIOSH REL: Exposure limits are A4 (Not Vapor: 0.5, STEL = 0.1 (ceiling, for Mercury, Classifiable Skin; Non-alkyl Mercury skin) Inorganic as a Human (Vacated Compounds: 0.1 DFG MAKs: Compounds Carcinogen) 1989 PEL) Ceiling, skin TWA = 0.1 (Vacated 1989 PEAK = 10 •MAK 30 PEL) min., momentary value Carcinogen: EPA-D; IARC-3, TLV-A4 NE = Not Established. See Section 16 for Definitions of Terms Used. NOTE: ALL WHMIS required information is included in appropriate sections based on the ANSI Z400.1-1998 format. This product has been classified in accordance with the hazard criteria of the CPR and the MSDS contains all the information required by the CPR. -

Water Quality Criteria

Office of Water EPA 823 -B -17 -001 2017 Water Quality Standards Handbook Chapter 3: Water Quality Criteria The WQS Handbook does not impose legally binding requirements on the EPA, states, tribes or the regulated community, nor does it confer legal rights or impose legal obligations upon any member of the public. The Clean Water Act (CWA) provisions and the EPA regulations described in this document contain legally binding requirements. This document does not constitute a regulation, nor does it change or substitute for any CWA provision or the EPA regulations. Water Quality Standards Handbook Chapter 3: Water Quality Criteria (40 CFR 131.11) Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 3.1 Water Quality Criteria ............................................................................................................................. 1 Toxic and Priority Pollutants ..................................................................................................................... 1 3.2 Forms of Water Quality Criteria .............................................................................................................. 4 3.2.1 Numeric Water Quality Criteria ....................................................................................................... 4 3.2.2 Narrative Water Quality Criteria ..................................................................................................... -

Water Quality and Biodiversity of Lønningsbekk Creek

Lønningsbekk 2014 WATER QUALITY AND BIODIVERSITY OF LØNNINGSBEKK CREEK Group 6 Siri Vatsø Haugum Eihab Idris Eugene Kitsios Imelda Rantty Kåre Andreas Thorsen The University of Bergen BIO 300 UiB Group 6 : Siri Vatsø Haugum, Eihab Idris, Eugene Kitsios, Imelda Rantty, Kåre Andreas Thorsen 1 Lønningsbekk 2014 Table of Contents 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 1.1 The environmental impact of concrete production……………………….. 4 1.2 Abiotic factors ………………………………………………………………………………. 5 1.3 Thermotolerant Coliform Bacteria ………………………………………………… 6 1.4 Phosphorus ………………………………………………………………………………….. 6 1.5 Benthic macroinvertebrates as ecological indicators …………………… 7 1.6 Aim of study 8 2. Materials and Methods ……………………………………………………………….. 9 2.1 Study area ……………………………………………………………………………………. 9 2.2 Sampling Procedures ……………………………………………………………………. 12 2.2.1 Thermotolerant Coliform Bacteria ………………………………………………… 12 2.2.2 Phosphorus…………………………………………………………………………………… 12 2.2.3 Temperature, conductivity, pH, dissolved oxygen, salinity and 13 velocity ………………………………………………………………………………………… 2.2.4 Creek Flow Rate …………………………………………………………………………… 13 2.2.5a Biodiversity …………………………………………………………………………………. 14 2.2.5b Laboratory investigations ……………………………………………………………. 14 2.2.5c Biodiversity analysis ……………………………………………………………………. 15 3. Results …………………………………………………………………………………………. 17 3.1 Thermotolerant Coliform Bacteria ………………………………………………… 17 3.2 Phosphorus ………………………………………………………………………………….. 18 3.3 Temperature, conductivity, pH, dissolved oxygen, salinity and 20 velocity …………………………………………………………………………………………. -

IPAC Recommendations for Use of Personal Protective Equipment for Care of Individuals with Suspect Or Confirmed COVID‑19

TECHNICAL BRIEF IPAC Recommendations for Use of Personal Protective Equipment for Care of Individuals with Suspect or Confirmed COVID‑19 6th Revision: May 2021 Introduction This document summarizes recommendations for infection prevention and control (IPAC) best practices for use of personal protective equipment (PPE) in health care settings. The document was updated to reflect the best available evidence at the time of writing. Updates to the document are noted in the Summary of Revisions. Please note that the Ministry of Health's Directive 5 is the provincial baseline standard for provision of personal protective equipment for hospitals, long-term care homes and retirement homes during COVID-19.1 Key Findings The primary mode of SARS-CoV-2 transmission is at short range through unprotected close contact and exposure to respiratory particles that range in size from large droplets, which fall quickly to the ground, to smaller droplets, also known as aerosols, which can remain suspended in the air. Outbreak case studies describe long-range transmission under the right set of favourable conditions (e.g., prolonged exposure in crowded, poorly ventilated spaces), implicating aerosols in transmission. Several studies demonstrate the effectiveness of current Infection Prevention and Control (IPAC) practices and personal protective equipment (PPE) when applied appropriately and consistently. Droplet and Contact Precautions continue to be recommended for the routine care of patients* with suspected or confirmed COVID‑19. Airborne Precautions should be used for aerosol generating medical procedures (AGMPs) planned or anticipated to be performed on patients with suspected or confirmed COVID‑19. Fully immunized staff should continue to use Droplet and Contact Precautions when caring for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19. -

Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality FIRST ADDENDUM to THIRD EDITION Volume 1 Recommendations WHO Library Cataloguing-In-Publication Data World Health Organization

Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality FIRST ADDENDUM TO THIRD EDITION Volume 1 Recommendations WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data World Health Organization. Guidelines for drinking-water quality [electronic resource] : incorporating first addendum. Vol. 1, Recommendations. – 3rd ed. Electronic version for the Web. 1.Potable water – standards. 2.Water – standards. 3.Water quality – standards. 4.Guidelines. I. Title. ISBN 92 4 154696 4 (NLM classification: WA 675) © World Health Organization 2006 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expres- sion of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters.