Shipwrecks-Friends-A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Military and Veterans' Health

Volume 16 Number 1 October 2007 Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health Deployment Health Surveillance Australian Defence Force Personnel Rehabilitation Blast Lung Injury and Lung Assist Devices Shell Shock The Journal of the Australian Military Medicine Association Every emergency is unique System solutions for Emergency, Transport and Disaster Medicine Different types of emergencies demand adaptable tools and support. We focus on providing innovative products developed with the user in mind. The result is a range of products that are tough, perfectly coordinated with each other and adaptable for every rescue operation. Weinmann (Australia) Pty. Ltd. – Melbourne T: +61-(0)3-95 43 91 97 E: [email protected] www.weinmann.de Weinmann (New Zealand) Ltd. – New Plymouth T: +64-(0)6-7 59 22 10 E: [email protected] www.weinmann.de Emergency_A4_4c_EN.indd 1 06.08.2007 9:29:06 Uhr Table of contents Editorial Inside this edition . 3 President’s message . 4 Editor’s message . 5 Commentary Initiating an Australian Deployment Health Surveillance Program . 6 Myers – The dawn of a new era . 8 Original Articles The Australian Defence Deployment Health Surveillance Program – InterFET Pilot Project . 9 Review Articles Rehabilitation of injured or ill ADF Members . 14 What is the effectiveness of lung assist devices in blast injury: A literature review . .17 Short Communications Unusual Poisons: Socrates’ Curse . 25 Reprinted Articles A contribution to the study of shell shock . 27 Every emergency is unique Operation Sumatra Assist Two . 32 System solutions for Emergency, Transport and Disaster Medicine Biography Surgeon Rear Admiral Lionel Lockwood . 35 Different types of emergencies demand adaptable tools and support. -

THE BATTLE of the CORAL SEA — an OVERVIEW by A.H

50 THE BATTLE OF THE CORAL SEA — AN OVERVIEW by A.H. Craig Captain Andrew H. Craig, RANEM, served in the RAN 1959 to 1988, was Commanding officer of 817 Squadron (Sea King helicopters), and served in Vietnam 1968-1979, with the RAN Helicopter Flight, Vietnam and No.9 Squadroom RAAF. From December 1941 to May 1942 Japanese armed forces had achieved a remarkable string of victories. Hong Kong, Malaya and Singapore were lost and US forces in the Philippines were in full retreat. Additionally, the Japanese had landed in Timor and bombed Darwin. The rapid successes had caught their strategic planners somewhat by surprise. The naval and army staffs eventually agreed on a compromise plan for future operations which would involve the invasion of New Guinea and the capture of Port Moresby and Tulagi. Known as Operation MO, the plan aimed to cut off the eastern sea approaches to Darwin and cut the lines of communication between Australia and the United States. Operation MO was highly complex and involved six separate naval forces. It aimed to seize the islands of Tulagi in the Solomons and Deboyne off the east coast of New Guinea. Both islands would then be used as bases for flying boats which would conduct patrols into the Coral Sea to protect the flank of the Moresby invasion force which would sail from Rabaul. That the Allied Forces were in the Coral Sea area in such strength in late April 1942 was no accident. Much crucial intelligence had been gained by the American ability to break the Japanese naval codes. -

An Analysis of the Loss of HMAS SYDNEY

An analysis of the loss of HMAS SYDNEY By David Kennedy The 6,830-ton modified Leander class cruiser HMAS SYDNEY THE MAIN STORY The sinking of cruiser HMAS SYDNEY by disguised German raider KORMORAN, and the delayed search for all 645 crew who perished 70 years ago, can be attributed directly to the personal control by British wartime leader Winston Churchill of top-secret Enigma intelligence decodes and his individual power. As First Lord of the Admiralty, then Prime Minster, Churchill had been denying top secret intelligence information to commanders at sea, and excluding Australian prime ministers from knowledge of Ultra decodes of German Enigma signals long before SYDNEY II was sunk by KORMORAN, disguised as the Dutch STRAAT MALAKKA, off north-Western Australia on November 19, 1941. Ongoing research also reveals that a wide, hands-on, operation led secretly from London in late 1941, accounted for the ignorance, confusion, slow reactions in Australia and a delayed search for survivors . in stark contrast to Churchill's direct part in the destruction by SYDNEY I of the German cruiser EMDEN 25 years before. Churchill was at the helm of one of his special operations, to sweep from the oceans disguised German raiders, their supply ships, and also blockade runners bound for Germany from Japan, when SYDNEY II was lost only 19 days before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and Southeast Asia. Covering up of a blunder, or a punitive example to the new and distrusted Labor government of John Curtin gone terribly wrong because of a covert German weapon, can explain stern and brief official statements at the time and whitewashes now, with Germany and Japan solidly within Western alliances. -

ETWEEN the Wars the Australian Army Nursing Service Existed Onl Y

CHAPTER 3 6 THE AUSTRALIAN ARMY NURSING SERVIC E ETWEEN the wars the Australian Army Nursing Service existed onl y B as a reserve, and in this respect was at a disadvantage compared with the British service, the Queen Alexandra Imperial Military Nursing Ser- vice, which had a permanent nucleus . In Australia records were kep t in each State of trained nurses appointed to the reserve and willing t o serve in time of national emergency, but the reservists were given n o training in military procedures, and no attempt was made to use their services even in militia training camps, from which the sick were sen t to civil hospitals. A matron-in-chief attached to the staff of the Director - General of Medical Services at Army Headquarters administered th e A.A.N.S., and in each State there was a principal matron who was respon- sible to the Deputy Director of Medical Services . The matron-in-chief an d principal matrons were required to give a certain number of days eac h year to military duty . From 1925 to 1940 the Matron-in-Chief was Miss G. M. Wilson. Late in 1940 Miss Wilson was sent overseas as Matron-in-Chief of the A .I.F. abroad, and Miss J. Sinclair Wood was appointed Matron-in-Chief a t Army Headquarters, where she served until 1943 . On her return to Aus- tralia in 1941 Miss Wilson retired . By this time Miss A . M. Sage, who had been in the Middle East, had also returned to Australia . Miss Sage took over as Matron-in-Chief, serving in this capacity until her retire- ment in 1952 . -

In Memory of the Officers and Men from Rye Who Gave Their Lives in the Great War Mcmxiv – Mcmxix (1914-1919)

IN MEMORY OF THE OFFICERS AND MEN FROM RYE WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES IN THE GREAT WAR MCMXIV – MCMXIX (1914-1919) ADAMS, JOSEPH. Rank: Second Lieutenant. Date of Death: 23/07/1916. Age: 32. Regiment/Service: Royal Sussex Regiment. 3rd Bn. attd. 2nd Bn. Panel Reference: Pier and Face 7 C. Memorial: THIEPVAL MEMORIAL Additional Information: Son of the late Mr. J. and Mrs. K. Adams. The CWGC Additional Information implies that by then his father had died (Kate died in 1907, prior to his father becoming Mayor). Name: Joseph Adams. Death Date: 23 Jul 1916. Rank: 2/Lieutenant. Regiment: Royal Sussex Regiment. Battalion: 3rd Battalion. Type of Casualty: Killed in action. Comments: Attached to 2nd Battalion. Name: Joseph Adams. Birth Date: 21 Feb 1882. Christening Date: 7 May 1882. Christening Place: Rye, Sussex. Father: Joseph Adams. Mother: Kate 1881 Census: Name: Kate Adams. Age: 24. Birth Year: abt 1857. Spouse: Joseph Adams. Born: Rye, Sussex. Family at Market Street, and corner of Lion Street. Joseph Adams, 21 printers manager; Kate Adams, 24; Percival Bray, 3, son in law (stepson?) born Winchelsea. 1891 Census: Name: Joseph Adams. Age: 9. Birth Year: abt 1882. Father's Name: Joseph Adams. Mother's Name: Kate Adams. Where born: Rye. Joseph Adams, aged 31 born Hastings, printer and stationer at 6, High Street, Rye. Kate Adams, aged 33, born Rye (Kate Bray). Percival A. Adams, aged 9, stepson, born Winchelsea (born Percival A Bray?). Arthur Adams, aged 6, born Rye; Caroline Tillman, aged 19, servant. 1901 Census: Name: Joseph Adams. Age: 19. Birth Year: abt 1882. -

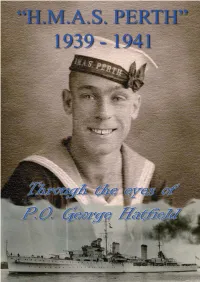

37845R CS3 Book Hatfield's Diaries.Indd

“H.M.A.S. PERTH” 1939 -1941 From the diaries of P.O. George Hatfield Published in Sydney Australia in 2009 Publishing layout and Cover Design by George Hatfield Jnr. Printed by Springwood Printing Co. Faulconbridge NSW 2776 1 2 Foreword Of all the ships that have flown the ensign of the Royal Australian Navy, there has never been one quite like the first HMAS Perth, a cruiser of the Second World War. In her short life of just less than three years as an Australian warship she sailed all the world’s great oceans, from the icy wastes of the North Atlantic to the steamy heat of the Indian Ocean and the far blue horizons of the Pacific. She survived a hurricane in the Caribbean and months of Italian and German bombing in the Mediterranean. One bomb hit her and nearly sank her. She fought the Italians at the Battle of Matapan in March, 1941, which was the last great fleet action of the British Royal Navy, and she was present in June that year off Syria when the three Australian services - Army, RAN and RAAF - fought together for the first time. Eventually, she was sunk in a heroic battle against an overwhelming Japanese force in the Java Sea off Indonesia in 1942. Fast and powerful and modern for her times, Perth was a light cruiser of some 7,000 tonnes, with a main armament of eight 6- inch guns, and a top speed of about 34 knots. She had a crew of about 650 men, give or take, most of them young men in their twenties. -

History of New South Wales from the Records

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that's often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google's system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us. -

RAN Ships Lost

CALL THE HANDS OCCASIONAL PAPER 6 Issue No. 6 March 2017 Royal Australian Navy Ships Honour Roll Given the 75th anniversary commemoration events taking place around Australia and overseas in 2017 to honour ships lost in the RAN’s darkest year, 1942 it is timely to reproduce the full list of Royal Australian Navy vessels lost since 1914. The table below was prepared by the Directorate of Strategic and Historical Studies in the RAN’s Sea Power Centre, Canberra lists 31 vessels lost along with a total of 1,736 lives. Vessel (* Denotes Date sunk Casualties Location Comments NAP/CPB ship taken up (Ships lost from trade. Only with ships appearing casualties on the Navy Lists highlighted) as commissioned vessels are included.) HMA Submarine 14-Sep-14 35 Vicinity of Disappeared following a patrol near AE1 Blanche Bay, Cape Gazelle, New Guinea. Thought New Guinea to have struck a coral reef near the mouth of Blanche Bay while submerged. HMA Submarine 30-Apr-15 0 Sea of Scuttled after action against Turkish AE2 Marmara, torpedo boat. All crew became POWs, Turkey four died in captivity. Wreck located in June 1998. HMAS Goorangai* 20-Nov-40 24 Port Phillip Collided with MV Duntroon. No Bay survivors. HMAS Waterhen 30-Jun-41 0 Off Sollum, Damaged by German aircraft 29 June Egypt 1941. Sank early the next morning. HMAS Sydney (II) 19-Nov-41 645 207 km from Sunk with all hands following action Steep Point against HSK Kormoran. Located 16- WA, Indian Mar-08. Ocean HMAS Parramatta 27-Nov-41 138 Approximately Sunk by German submarine. -

There Is a Kaleido- Scope of Talent in the Navy and I Know a Lot Of.Guys Who Are Willing to Put It to Use.”

Uniform changes New @&et und sweater authorized Navy black jacket, 55/45 polyester/wool with a stand-upknit collar, has been approved for optional wear by officers and chief petty officers with service and work- ing uniforms(summer khaki, summer white,A winter blue, winter working blue and working khaki).Additionally, the jacket is authorized for wear in lieu of the service dress blue coat whenthe service dress blue uniform is worn. The wooly-pulley sweater is an option with this combination. (The jacket is an option for Navy lchalti and black (blue)jackets, not a replace- ment.) The jacket will soon be available at Navy. Exchange Uniform Shops or can be ordered through the Uniform I I Support Center,Suite 200, 1545 Crossways Blvd. Che- sapealze, Va. 23320 (1-800-368-4088].The jacket is worn in the same manneras the Navy lzhalti and black (blue) jackets. Ablack V-neck style pullover sweater .has been approved to replace the blue crew neck (wooly-pulley). The V-neck style sweater is available in bothlight (acrylic] andheavy (wool)weaves and will be wornin the same manneras the blue wooly-pulley sweater.The blue wooly-pulleysweater is authorized for optional wear until Oct. 1, 1995. After this date, the bluewooly-pulley may not be worn .ashore. However, a ship’s commanding officer can authorize the blue wooly-pulleyfor shipboard wear. See NavAdmin 139/93 for details. I I I pssed over for promotion to commander and seniorchief and masterchief etty afficers in 61 overmanned ratings willbe eligible for the new 15-plus year tirement program recently approved by DoD. -

The Lower Bathyal and Abyssal Seafloor Fauna of Eastern Australia T

O’Hara et al. Marine Biodiversity Records (2020) 13:11 https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-020-00194-1 RESEARCH Open Access The lower bathyal and abyssal seafloor fauna of eastern Australia T. D. O’Hara1* , A. Williams2, S. T. Ahyong3, P. Alderslade2, T. Alvestad4, D. Bray1, I. Burghardt3, N. Budaeva4, F. Criscione3, A. L. Crowther5, M. Ekins6, M. Eléaume7, C. A. Farrelly1, J. K. Finn1, M. N. Georgieva8, A. Graham9, M. Gomon1, K. Gowlett-Holmes2, L. M. Gunton3, A. Hallan3, A. M. Hosie10, P. Hutchings3,11, H. Kise12, F. Köhler3, J. A. Konsgrud4, E. Kupriyanova3,11,C.C.Lu1, M. Mackenzie1, C. Mah13, H. MacIntosh1, K. L. Merrin1, A. Miskelly3, M. L. Mitchell1, K. Moore14, A. Murray3,P.M.O’Loughlin1, H. Paxton3,11, J. J. Pogonoski9, D. Staples1, J. E. Watson1, R. S. Wilson1, J. Zhang3,15 and N. J. Bax2,16 Abstract Background: Our knowledge of the benthic fauna at lower bathyal to abyssal (LBA, > 2000 m) depths off Eastern Australia was very limited with only a few samples having been collected from these habitats over the last 150 years. In May–June 2017, the IN2017_V03 expedition of the RV Investigator sampled LBA benthic communities along the lower slope and abyss of Australia’s eastern margin from off mid-Tasmania (42°S) to the Coral Sea (23°S), with particular emphasis on describing and analysing patterns of biodiversity that occur within a newly declared network of offshore marine parks. Methods: The study design was to deploy a 4 m (metal) beam trawl and Brenke sled to collect samples on soft sediment substrata at the target seafloor depths of 2500 and 4000 m at every 1.5 degrees of latitude along the western boundary of the Tasman Sea from 42° to 23°S, traversing seven Australian Marine Parks. -

Visioning of the Coral Sea Marine Park

2020 5 AUSTRALIA VISIONING THE CORAL SEA MARINE PARK #VisioningCoralSea 04/29/2020 - 06/15/2020 James Cook University, The University of Cairns, Australia Sydney, Geoscience Australia, Queensland Dr. Robin Beaman Museum, Museum of Tropical Queensland, Biopixel, Coral Sea Foundation, Parks Australia Expedition Objectives Within Australia’s largest marine reserve, the recently established Coral Sea Marine Geological Evolution Insight Park, lies the Queensland Plateau, one of the To collect visual data to allow the understanding of the world’s largest continental margin plateaus physical and temporal changes that have occurred at nearly 300,000 square kilometers. Here historically on the Queensland Plateau. a wide variety of reef systems range from large atolls and long banks to shallow coral pinnacles. This region is virtually unmapped. This project addresses a range of priorities Mapping Seafloor of the Australian Government in terms of mapping and characterizing a poorly known To map, in detail, the steeper reef flanks using frontier area of the Australian marine estate. high-resolution multibeam mapping. The seabed mapping of reefs and seamounts in the Coral Sea Marine Park is a high priority for Parks Australia, the managers of ROV Expedition Australia’s Commonwealth Marine Parks. The new multibeam data acquired will be To document deep-sea faunas and their habitats, as added to the national bathymetry database well as the biodiversity and distribution patterns of hosted by Geoscience Australia and released these unexplored ecosystems. Additionally, the ROV through the AusSeabed Data Portal. dives will help to determine the extent and depth of coral bleaching. REPORT IMPACT 6 We celebrated World Ocean Day during the expedition with a livestream bringing together Falkor ́s crew with scientist, students, and athletes to share their ocean experiences. -

February 2010 VOL

Registered by AUSTRALIA POST NO. PP607128/00001 THE February 2010 VOL. 33 No.1 The official journal of The ReTuRNed & ServiceS League OF austraLia POSTAGE PAID SURFACE ListeningListeningWa Branch incorporated • PO Box 3023 adelaide Tce, Perth 6832 • est. 1920 PostPostAUSTRALIA MAIL Toodyay Remembered RSL gratefully acknowledges the financial support from the Veteran Community and the Aged Fund. Australia Day Legal How I Readers Awards Loopholes Lost Weight Satisfactory Page Page Page Survey 15 Legal Loopholes 21 22 Page 28 Rick Hart - Proudly supporting your local RSL Belmont 9373 4400 COUNTRY STORES BunBury SuperStore 9722 6200 AlBAny - kitcHen & LaunDrY onLY 9842 1855 CIty meGAStore 9227 4100 Broome 9192 3399 ClAremont 9284 3699 BunBury SuperStore 9722 6200 JoondAlup SuperStore 9301 4833 kAtAnnInG 9821 1577 mAndurAh SuperStore 9586 4700 Country CAllerS FreeCAll 1800 654 599 mIdlAnd SuperStore 9267 9700 o’Connor SuperStore 9337 7822 oSBorne pArk SuperStore 9445 5000 VIC pArk - Park Discount suPerstore 9470 4949 RSL Members receive special pricing. “We won’t be beaten on price. I put my name on it.”* Just show your membership card! 2 The ListeNiNg Post February 2010 Delivering Complete Satisfaction Northside 14 Berriman drive, wangara phone: 6400 0950 09 Micra 5 door iT’S A great movE automatic TiidA ST • Powerful 1.4L engine sedan or • 4 sp automatic hatch • DOHC • Air conditioning • Power steering • CD player # # • ABS Brakes • Dual Front Airbags $15,715 $16,490 • 6 Speed Manual # dRiveaway# Applicable to TPI card holders only. Manual. Metallic colours $395 extra dRiveaway Applicable to TPI card holders only. Manual. Metallic colours $395 extra movE into A dualiS NAvara turbO diesel ThE all new RX 4X4 dualiS st LiMited stock # # • ABS Brakes • Dual Airbags • CD Player • Dual SRS Airbags , $35,490 • 3000kg Towing Capacity $24860 • Air Conditioning # dRiveaway# Applicable to TPI card holders only.