Cushing, Nancy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Memory of the Officers and Men from Rye Who Gave Their Lives in the Great War Mcmxiv – Mcmxix (1914-1919)

IN MEMORY OF THE OFFICERS AND MEN FROM RYE WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES IN THE GREAT WAR MCMXIV – MCMXIX (1914-1919) ADAMS, JOSEPH. Rank: Second Lieutenant. Date of Death: 23/07/1916. Age: 32. Regiment/Service: Royal Sussex Regiment. 3rd Bn. attd. 2nd Bn. Panel Reference: Pier and Face 7 C. Memorial: THIEPVAL MEMORIAL Additional Information: Son of the late Mr. J. and Mrs. K. Adams. The CWGC Additional Information implies that by then his father had died (Kate died in 1907, prior to his father becoming Mayor). Name: Joseph Adams. Death Date: 23 Jul 1916. Rank: 2/Lieutenant. Regiment: Royal Sussex Regiment. Battalion: 3rd Battalion. Type of Casualty: Killed in action. Comments: Attached to 2nd Battalion. Name: Joseph Adams. Birth Date: 21 Feb 1882. Christening Date: 7 May 1882. Christening Place: Rye, Sussex. Father: Joseph Adams. Mother: Kate 1881 Census: Name: Kate Adams. Age: 24. Birth Year: abt 1857. Spouse: Joseph Adams. Born: Rye, Sussex. Family at Market Street, and corner of Lion Street. Joseph Adams, 21 printers manager; Kate Adams, 24; Percival Bray, 3, son in law (stepson?) born Winchelsea. 1891 Census: Name: Joseph Adams. Age: 9. Birth Year: abt 1882. Father's Name: Joseph Adams. Mother's Name: Kate Adams. Where born: Rye. Joseph Adams, aged 31 born Hastings, printer and stationer at 6, High Street, Rye. Kate Adams, aged 33, born Rye (Kate Bray). Percival A. Adams, aged 9, stepson, born Winchelsea (born Percival A Bray?). Arthur Adams, aged 6, born Rye; Caroline Tillman, aged 19, servant. 1901 Census: Name: Joseph Adams. Age: 19. Birth Year: abt 1882. -

Experiencing the Identity(Ies) of the Other(S)

Experiencing the identity(ies) of the other(s), finding that of one’s own on/through the stage in Wertenbaker’s play Our Country’s Good Autor(es): Kara, enay Publicado por: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/43216 DOI: DOI:https://doi.org/10.14195/978-989-26-1483-0_9 Accessed : 25-Sep-2021 07:37:43 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. pombalina.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt ANA PAULA ARNAUT ANA PAULA IDENTITY(IES) A MULTICULTURAL AND (ORG.) MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH ANA -

History of New South Wales from the Records

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that's often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google's system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us. -

Life on Board

Supported by the Sydney Mechanics’ School of the Arts Life on Board Australian Curriculum: Stage 5 – The Making of the Modern World – Depth Study 1 (Making a Better World) – Movement of Peoples (1750-1901) Australian Curriculum - Content ACOKFH015: The nature and extent of the movement of peoples in the period (slaves, convicts and settlers) ACDSEH083: The experience of slaves, convicts and free settlers upon departure, their journey abroad, and their reactions on arrival, including the Australian experience Australian Curriculum – Historical Skills ACHHS165: Use historical terms and concepts ACHHS170: Process and synthesise information from a range of sources for use as evidence in an historical argument NSW Syllabus: Stage 5 – The Making of the Modern World – Depth Study 1 (Making a Better World) – Topic 1b: Movement of Peoples (1750-1901) NSW Syllabus - Outcomes HT5-6: Uses relevant evidence from sources to support historical narratives, explanations and analyses of the modern world and Australia 1 Supported by the Sydney Mechanics’ School of the Arts HT5-9: Applies a range of relevant historical terms and concepts when communicating an understanding of the past Assumed Knowledge ACDSEH018: The influence of the Industrial Revolution on the movement of peoples throughout the world, including the transatlantic slave trade and convict transportation Key Inquiry Questions What was the experience of convicts during their journey to Australia? 2 Supported by the Sydney Mechanics’ School of the Arts Time: Activity overview: Resources 40 -45 mins Students are given the ‘Life on Board’ worksheet and Dictionary of Sydney articles: a copy of the article on the ship the Charlotte. As a class, teacher and students work through the article First Fleet picking out the information that indicates the nature of life on board a First Fleet ship. -

SINKING of HMS SIRIUS – 225Th ANNIVERSARY

1788 AD Magazine of the Fellowship of First Fleeters Inc. ACN 003 223 425 PATRON: Professor The Honourable Dame Marie Bashir AD CVO Volume 46, Issue 3 47th Year of Publication June/July 2015 To live on in the hearts and minds of descendants is never to die SINKING OF HMS SIRIUS – 225th ANNIVERSARY A Report from Robyn Stanford, Tour Organiser. on the Monday evening as some of the group had arrived on Saturday and others even on the Monday afternoon. Graeme Forty-five descendants of Norfolk Island First Fleeters and Henderson & Myra Stanbury, members of the team who had friends flew to Norfolk Island to celebrate the 225th anniver- helped in raising the relics from the Sirius, were the guest sary of the 19th March 1790 midday sinking of HMS Sirius. As speakers at this function and we all enjoyed a wonderful fish well as descendants of Peter Hibbs, in whose name the trip fry, salads & desserts and tea or coffee. was organised as a reunion, members of our travel group were descended from James Bryan Cullen, Matthew Everingham, A special request had been to have a tour with the historian, Anne Forbes, James Morrisby, Edward Risby & James Wil- Arthur Evans who has a massive knowledge about the is- lams. land. Taking in the waterfront of Kingston, Point Hunter, where he pointed out examples of volcanic rock & the solitary The Progres- Lone Pine noted by Captain Cook on his second voyage Arthur sive Dinner on also gave a comprehensive talk on the workings of the Lime the night of Kilns, and the Salt House with its nearby rock-hewn water tub. -

Towards a Minor Theatre: the Task of the Playmaker in Our Country’S Good

Wenshan Review of Literature and Culture.Vol 5.2.June 2012.25-48. Towards a Minor Theatre: The Task of the Playmaker in Our Country’s Good Carol L. Yang ABSTRACT Timberlake Wertenbaker’s play Our Country’s Good (1988), as an adaptation of Thomas Keneally’s novel The Playmaker (1987), traces how a group of convicts, who are isolated in an eighteenth-century Australian penal colony, work together to produce George Farquhar’s The Recruiting Officer in celebration of the birthday of King George III. Arguably, Our Country’s Good is characterized by a kind of metatheatrical minorization of the major, a subtraction of the official State representatives, such as history, power structure, society, language, and text; the play is characterized by a polemicizing the sense of other spaces, and a form of threshold traversing that is rendered possible in the context of translation/adaptation and dramatic text/performance text in the theatre. This paper aims to analyze Wertenbaker’s Our Country’s Good in terms of Gilles Deleuze’s and Félix Guattari’s theories—such as the concepts of deterritorialization, reterritorialization, lines of flight, and minor theatre—in order to explore how the dispossessed convicts traverse the threshold of “becoming other” via the historicized immigration of transportation, which opens up lines of flight and generates the unceasing mapping of a new life. I would like to suggest that Wertenbaker’s Our Country’s Good presents a subtle counterpoint between the major theatre and the minor theatre: whereas a major theatre seeks to represent and to reproduce the power structure of the dominant state apparatus, the minor theatre operates by disseminating, varying, subverting the structures of the state and major theatre. -

HMS Sirius Shipwreck Factsheet

Decemeber 2011 THE HMS SIRIUS The shipwreck of the HMS Sirius is one our most significant links to a vessel of the First Fleet. Located in Commonwealth waters, south east of Kingston Pier in Slaughter Bay, Norfolk Island, the archaeological remains of the HMS Sirius are the only known in-situ remains of a vessel of the First Fleet. The HMS Sirius was inscribed on the National Under the command of John Hunter, the Sirius Heritage List on 25 October 2011, the 225th survived a treacherous nine month round trip anniversary of the commissioning of the HMS to bring much needed supplies to the colony. Sirius and the appointment of Arthur Philip as On its return the ship was closely examined Captain and commander of the First Fleet. and spent the following four months undergoing The shipwreck of the HMS Sirius is of much needed repairs from storm damage and outstanding heritage value to the nation as other defects. evidence of one of the most defining moments During this time the situation for the colony of Australia’s history. became critical as the settlement failed in its The shipwreck of the HMS Sirius is the 97th early attempts at self-sufficiency. The HMS place to be included in the National Heritage Guardian was dispatched from England in List. September in 1789 to re-supply the colony but it failed to reach Australia. By February 1790 the Guardian and lifeline of early colonial shortage of supplies at Port Jackson was acute Australia and the settlement was in danger of starvation and abandonment. -

Port Jackson Transcripts

Port Jackson – Journal and letter Transcripts A Journal of a voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China in the Lady Penrhyn, Merchantman William Cropton Server, Commander by Arthur Bowes Smyth, Surgeon, Jan-Feb, 1788 Manuscript Safe 1/15 Arthur Bowes Smyth (1750-1790), known as Bowes while in the colony, sailed with the First Fleet as Surgeon on board the Lady Penrhyn. He was responsible for the women convicts. Bowes Smyth took a great interest in natural history, collecting specimens and making drawings including the earliest extant illustration by a European of the emu. It is probably not the first sketch of an emu, as has sometimes been claimed; this may have been drawn by Lieutenant John Watts, also of the Lady Penrhyn, reproduced in Arthur Phillip's published account of the First Fleet and now lost. He returned to England on the Lady Penrhyn travelling via Lord Howe Island, Tahiti, China and St Helena. On Lord Howe Island he described or drew six of the islands birds. Three, including, the white gallinule, are now extinct, and a fourth is rare. Bowes Smyth arrived in England in August 1789. He died some months after his return and was buried on 31 March 1790 in Tolleshunt D'Arcy, Essex, where he had been born Jany. 23d. This day the Governor return'd from exploring the Coast & determin'd to go to Port Jackson, abt. 5 miles distant from Botany Bay by land, but 10 or 12 by Sea. This is Certainly in the Opinion of everyone one of the finest Harbours in the World, not excepting that of Trincamale in the East Indies, & was the adjacent Country fertile instead of being so barren as it is, it wd. -

L3-First-Fleet.Pdf

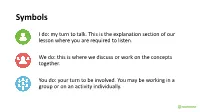

Symbols I do: my turn to talk. This is the explanation section of our lesson where you are required to listen. We do: this is where we discuss or work on the concepts together. You do: your turn to be involved. You may be working in a group or on an activity individually. Life in Britain During the 1700s In the 1700s, Britain was the wealthiest country in the world. Rich people could provide their children with food, nice clothes, a warm house and an education. While some people were rich, others were poor. Poor people had no money and no food. They had to work as servants for the rich. Poor children did not attend school. When machines were invented, many people lost their jobs because workers were no longer needed. Health conditions during the 1700s were very poor. There was no clean water due to the pollution from factories. Manure from horses attracted flies, which spread diseases. A lack of medical care meant many people died from these diseases. Life in Britain During the 1700s • The overcrowded city streets were not a nice place to be during the 1700s. High levels of poverty resulted in a lot of crime. • Harsh punishments were put in place to try to stop the crime. People were convicted for crimes as small as stealing bread. Soon, the prisons became overcrowded with convicts. • One of the most common punishments was transportation to another country. Until 1782, Britain sent their convicts to America. After the War of Independence in 1783, America refused to take Britain’s convicts. -

Royal Australian Navy Vietnam Veterans

Editor: Tony (Doc) Holliday Email: [email protected] Mobile: 0403026916 Volume 1 September 2018 Issue 3 Greenbank Sub Section: News and Events………September / October 2018. Saturday 01 September 2018 1000-1400 Merchant Marine Service Tuesday 04 September 2018 1930-2100 Normal Meeting RSL Rooms Wednesday 26 September 2018 1000 Executive Meeting RSL Rooms Tuesday 02 October 2018 1930-2100 Normal Meeting RSL Rooms Wednesday 31 October 2018 1000 Executive Meeting RSL Rooms Sausage Sizzles: Bunnings, Browns Plains. Friday 14 September 2018 0600-1600 Executive Members of Greenbank Sub. Section President Michael Brophy Secretary Brian Flood Treasurer Henk Winkeler Vice President John Ford Vice President Tony Holliday State Delegate John Ford Vietnam Veterans Service 18August 22018 Service was held at the Greenbank RSL Services Club. Wreath laid by Gary Alridge for Royal Australian Navy Vietnam Veterans. Wreath laid by Michael Brophy on behalf of NAA Sub Section Greenbank. It is with sadness that this issue of the Newsletter announces the passing of our immediate past President and Editor of the Newsletter. Len Kingston-Kerr. Len passed away in his sleep in the early hours of Tuesday 21st August 2018. As per Len’s wishes, there will be no funeral, Len will be cremated at a private service and his ashes scattered at sea by the Royal Australian Navy. A wake will be held at Greenbank RSL in due course. 1 ROYAL AUSTRALIAN NAVY ADMIRALS: Rear Admiral James Vincent Goldrick AO, CSC. James Goldrick was born in Sydney NSW in 1958. He joined the Royal Australian Navy in 1974 as a fifteen-year-old Cadet Midshipman. -

Genealogy and Family History John Clarke Wenham

GENEALOGY AND FAMILY HISTORY of the Descendants of JOHN CLARKE of WENHAM, MASSACHUSETTS and EXETER, NEW HAMPSHIRE Compiled by MARLENE A. HINKLEY Bath, Maine Copyright 1968 Marlene A. Hinkley FOREWARD The main purpose in mind in compiling this genealogy was to combine research material obtained from many sources into one book to be of assistance to others in searching their ancestry. As will be seen, there are many family lines throughout this book about which nothing could be found, due to the lack of public records in many instances. Many abbreviations have been used in this book, some of which are as follows: b. born d. died m. married (marriage unm. unmarried int. intentions div. divorced res. resided (residence) emp. employed use U.S. Census The system used in compiling the information in this book is a rela tively easy one to follow. Each child is listed under his or her parent, in order of birth, if known, and, if the child bad issue which is not listed on the same page, that child is given a number which is inserted in the margin to the left of his or her name. Further information concerning that child and his or her children may be obtained by following through the book the numbers to the extreme left of each page, indicating those descendants who are heads of a household. There is an index at the end of this book which consists of the names of all persons contained herein. Any particular ancestor may be easily found by checking this index. A list of all sources from which material and information have been obtained for the preparation of this book may be found at the very end just preceding the index. -

OLD PATTERN ADMIRALTY LONG SHANKED ANCHOR North Head

OLD PATTERN ADMIRALTY LONG SHANKED ANCHOR North Head, Sydney CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN April, 2000 Heritage Office NSW AUSTRALIA Project leader: David Nutley Research and Report Preparation: Tim Smith Report Released: April, 2000. © NSW Heritage Office, Sydney NSW, Australia The material contained within may be quoted with appropriate attribution. Disclaimer Any representation, statement, opinion or advice, expressed or implied in this publication is made in good faith but on the basis that the State of New South Wales, its agents and employees are not liable (whether by reason of negligence, lack of care or otherwise) to any person for any damage or loss whatsoever which has occurred or may occur in relation to that person taking or not taking (as the case may be) action in respect of any representation, statement or advice referred to above. Cover: Drawing of the Old Plan Admiralty anchor discovered off North Head, Port Jackson (Sydney). Drawing by Tim Smith. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Heritage Office wishes to thank the following individuals for their assistance with the Sydney anchor survey: Mr John Riley Site discoverer Ms Sue Bassett Conservator, Australian National Maritime Museum, Sydney. Mr Colin Browne Manly Hydraulics Laboratory (MHL), Department of Mr Phil Clark Public Works & Services Mr John Carpenter Materials Conservator, Western Australian Maritime Museum Mr Bill Jeffery State Heritage Branch. South Australia. Mr Mike Nash Cultural Heritage Branch, Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment. Tasmania. Ms Frances Prentice Librarian, Australian National Maritime Museum Dr Richard Smith Freelance underwater video Ms Myra Stanbury Western Australian Maritime Museum. Fremantle. OLD PATTERN ADMIRALTY LONG SHANKED ANCHOR CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction Page 1 2.0 Objectives 3 2.1 General 3 2.2 Specific 3 2.3 Methodology 3 2.4 Position 4 3.0 Historical Analysis 5 3.1 “Here an anchor ..